by Ian Campbell

© all rights reserved

We stand on the threshold of another Australian Spring – a particular time when the whole land is in beauty, arrayed with Wattles all abloom in the most exquisite tints and tones of yellow, and there from is ascending like a continual oblation, an invisible cloud, the soft, sweet perfume of pure wattle incense.

These are not my words, but rather the opening lines in my late grandfather’s seminal short book or photographic essay on Australian wattles titled, Golden wattle, our national floral emblem, published in September 1921. Archibald James Campbell (1853-1929) – known usually as ‘AJ’ – was a pioneer enthusiast and promoter of wattles, particularly Golden Wattle Acacia pycnantha, as the national floral emblem, during the early years of Australia’s story as a federated nation. As far back as 1899, AJ had promoted a private ‘Wattle Club’ that annually visited such places in Victoria as Werribee, the You Yangs, and Eltham on the Yarra – about 1 September – to enjoy the ‘Wattle Wilds’. In his personal diary of events over the years, there is a note against the year, 1899, which reads simply – ‘wattles at Werribee’.2

Almost one hundred years ago on 8 September 1908, AJ first delivered what he called a Lantern Lecture – a lecture illustrated with optical lantern slides – as they were termed. At that lecture, which he titled, ‘Wattle Time, or Yellow- haired September’, given to an audience of the Photographic Clubs of Melbourne Technical College, he suggested a ‘Wattle Day’ – to celebrate the wattle and give symbolic expression to the relationship between inhabitants of the newly federated Commonwealth of Australia and their natural environment. This initial lecture, and the many similar ones that followed it, formed the basis for his 1921 book, more correctly, a photographic essay, in which he set out in definitive form the case for wattle as the national floral emblem.

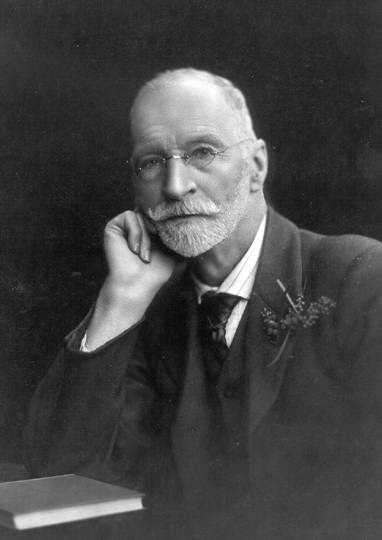

Figure 1: Archibald James Campbell (1853-1929). Author of Golden wattle, our national floral emblem.

In this paper I would like to reflect on AJ’s background and life, and also to explore some aspects of Golden Wattle and the national audience for whom the book was written. I am neither botanist nor taxonomist, neither scientist or historian, but simply a descendant of one who saw and experienced Nature around him and who believed it deserved praise. My own interests in literature also inform my writing and also the legacy of my late parents, Duncan and Mary Campbell, who were during their lifetimes, practitioners in the field of landscape architecture/or gardening, in nature conservation and related fields in Sydney in the 1960s.

I am conscious too, of the need to join together the knowledge that has often been all-too- readily neglected, of Aboriginal perspectives on the rhythm of Nature, with those of the settlers who came later. In this respect I note the present work of the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, particularly in the new Australian Garden at Cranbourne, to work in partnership with the Boonerwurrung people to build such knowledge.

AJ Campbell’s genealogy

AJ Campbell made a significant contribution to defining a field of ‘Australian nature studies’, a genre elaborated in books by Tom Griffiths, particularly Hunters and collectorsand Forests of ash. More recently, Libby Robin’s history of Australian ornithology, The flight of the emu, gave prominent coverage to my late grandfather as a pioneer in the field of Australian ornithology. In papers – and in her forthcoming book, How a continent created a nation – she has outlined the way in which my late grandfather played a significant role in aligning Australian nature with symbols of nationalism, and our growth as a federated country. I want to add a few additional dimensions to the outstanding accounts the two historians have written about the history of the Australian experience in interacting with our natural environment and the marvellous notes on the internet gathered on the World Wide Wattle site.3

On 4 February 1840, AJs father, originally from Glasgow, sailed from Liverpool, England, on the Statesman . He went ashore in Melbourne for the first time on 21 June 1840. AJ Campbell was born on 18 February 1853 at John St, Fitzroy. The family had tried squatting in the Werribee river area, but by 1861 had lost all and returned to Melbourne . At ten years of age, AJ had his first job delivering papers. By 1866, aged just 13 years, he entered the Victorian Government Education Service as a clerk. By 1869 he had moved in the Government Service to take up a job in the Victorian Government Customs Department, becoming a member of the Landing staff as a weigher. He took a Civil Service exam in 1874, and remained in the Customs Department until 1914, which after Federation in 1901 had become a part of the Commonwealth Government. He retired after 45 years of service. Apart from any training within the civil service, the only formal training he seems to have undertaken in his life was a photography course in 1891-92 at the Melbourne Working Men’s College.

AJ grew up with an interest in nature, particularly ornithology, with weekend excursions around Melbourne, then gradually extending much further afield. In 1885, he visited North Queensland, and between 1887 and 1891, he variously visited Western Australia, Bass Strait islands and the ‘Big Scrub’ in New South Wales in pursuit of his ornithological interests. On 21 November 1889 on an excursion to Rottnest Island, Western Australia, he photographed sea birds in flight, perhaps the first such photograph in the Australian context. He contributed articles on nature, and particularly about his ornithological excursions to the Melbourne paper, The Australasian, for about forty years. But his magnum opus was the publication in 1900 of the huge 1,100 page two volume edition of Nests and eggs of Australian birds . It was a major achievement in the field of Australian natural history, compiled by one without tertiary training in his spare time after work. AJ always had an interest in wattles from his early days growing up in the areas around Werribee and Melton. But it was in the field of Australian ornithology that his impact was most profound, particularly in the early years of the twentieth century. As a leading systematist, he had both ‘wins’ and ‘losses’ in some tensely fought discussions about naming Australian birds.

In 1910, AJ Campbell established a branch of the Wattle League in Victoria . In this year ‘Wattle Day’ was celebrated in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia . The first ‘Wattle train’, which ran from Melbourne to Hurstbridge in Victoria on 31 August 1912, carried 980 passengers. On the initiative of South Australian, Sir William Sowden, who later provided a forward for AJ’s 1921 publication, the Wattle Day League federalised at Melbourne on 8 January 1913. The same year his eldest son, AG Campbell, purchased a property in Kilsyth from Meyer Bros, which he called ‘Acacia Orchard’, and proceeded to plant it with over three hundred wattle trees. These were all activities in which my grandfather played a role, and he continued active in wattle activities until his death in 1929.4

AJ Campbell’s papers and photographs

In 2002, I donated to the National Library of Australia in Canberra those papers, photographs and ephemera relating to my grandfather’s life and work that were in the possession of my late father, Duncan Campbell, born 1918, AJ’s youngest and last surviving child. My own appreciation of AJ’s work stemmed from childhood memories of AJ’s books, Nests and eggs of Australian birds, and Golden wattle . There had always been a photograph of my late grandfather hanging in a room at our Sydney home. But in leafing through AJ’s papers and photographs, two things struck me in particular. One was his often excellent, and always interesting, nature-writing; the other was his photographic skills. I felt that his role in promotion of the wattle through the photographic essay technique, was worthy of greater note . I resolved to seek to place the photos and papers in our National Library in recognition of this and to ensure that future generations had access to these papers, ephemera and photographs. This placement is in addition to the holdings that my grandfather and his widow had themselves placed in the Museum of Victoria in the 1920s, which primarily related to his ornithological interests.5

Wattle Time or ‘Yellow haired September’ ( Kendall )

My purpose now is to explore some of the aspects of AJ’s 1921 publication in which he describes the various species of acacia that flower across the various months of the year in different parts of Australia, starting a few of the well known species that flower in July. But the book gives pre-eminence to the wattles that flower in September. He also weaves in Australian poetry particularly that of Henry Kendall, with September, linking the ideas of the season of spring with the feminine, and with the glories of the colour yellow associated with acacias. Allan McEvey, in his contribution on Campbell to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, commented that some of his writings were ‘forced’.6 I do agree at times with that assessment. Rather, taken in their entirety, and noting a ‘multimedia approach’ from one born well before the digital age, I can only find the totalityof his achievement remarkable. Let me continue with some further passages from his 1921 book – given that I have already read to you his opening lines with their first appeal to our senses of sight and smell. AJ continues:

Away back in the immeasurable past, at the dawn of Creation, when ‘the earth was without form and void,’ ‘the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters’. The ‘Divine Breath’ of the same Sevenfold Spirit moves today on the face of the earth, as manifested in the wonderful and silent development of floral stores of ‘Yellow Haired September’; and with what a bountiful hand this wealth of Wattle is lavished! What prodigal liberality of Him who ‘is perfect in knowledge’!

We can see here AJ drawing a direct causal link between his belief in the Divine and the ‘manifestation’ of the Creator in the ‘floral stores’ of wattles. The existence of nature, in this form, is evidence for him that the Divine purpose is one that lays out such a bounty. The task of Humankind, in this schema of belief, is, by implication, to find, discern and appreciate the Divine in nature. In referring to ‘Yellow Haired September’ AJ also introduces the first in a series of allusions throughout the book to phrases from the poetry of Henry Kendall (1841-1882), notably from the poems, ‘September in Australia ‘ and ‘Bellbirds’. The words used in these poems often align, in a very direct manner, the idea of association between the changing seasons, and the suggestion that especially the months of September, and even October, can best be perceived as having ‘feminine characteristics’, of which the most striking are the tresses of hair.

Then AJ adopts a different tack. He goes on:

Were we to ascend above this city to an altitude where we could obtain a bird’s-eye view of our State, and with an eagle’s vision scan the land from end to end, from Cape Howe to the once-disputed parallel, we would see the sinuous course of rivers traced, more or less, in yellow from the golden tops of regiments of waterside, or so-called Silver Wattles ( Acacia dealbata ) that line the streams: the Yarra Yarra, like a mid-rib of a huge leaf with branching veins right and left; the Upper Murray with its lengthened feeders – Goulburn, Mitta Mitta and the like; the Thompson and Latrobe, with rich alluvial flats; the winding Mitchell; the rapidly running Snowy; not to mention the Yarram Yarram, and more southerly streams of Gippsland, and all the intervening network of rivers and rivulets. Imagine the grandeur of such a living landscape map, with rivers marked with rich lemon chrome, and you will gain some idea of the abundance and beauty of September’s Yellow hair.

But these shining tracks of yellow are not confined to streams alone. The mountain forms wear a cloth of gold from various other kinds of Wattles, and even in that wilderness, the Mallee – a wilderness in the sense of wild verdure – the breaks between the scrub are illuminated with the choicest Wattle bushes, dressed in lemon yellow.

It is interesting to reflect here that even while he does not flinch from using the term ‘wilderness’ to describe the Mallee region, he qualifies this to ensure his readers understand that he does not regard the area as one that has ‘no value’, as might have been the thoughts of some of his contemporaries. Rather, the area has ‘wild verdure’. As an ornithologist, it is almost certain that he had long ago come to the realisation that such regions were often rich in bird life and other aspects of nature.

In all this realm of aurelian beauty, where to begin to individualise the species perplexes one. Approximately, there are about 500 species of Acacia flora in the world, of which perhaps over 400 are Australian; therefore, by numbers, the Wattle is almost exclusively Australian, and should undoubtedly be our National Flower.7

Interestingly, despite controversies that did develop, especially in New South Wales, regarding the claims of other flowers, such as the waratah, to be regarded as a national floral emblem, AJ simply concentrates on putting the exclusive case for the wattle and does not seek to rebut or contrast its claims with that of any other Australian species:

We are not concerned with any mundane material such as commercialism, that is, the great economic value of Wattle-bark for the amount of tannic acid it contains, or the value of Wattle-wood for furniture when beautified by the polisher’s art, etc., but briefly to consider the aesthetic side of Wattles, their shapely forms, the perfect beauty of their soft flowering masses, and the goodly fragrance of some of the species: and as our theme, ‘Yellow-haired September’ with her plaits of gold, is suggestive of the female gender, it may be supposed that many of our pictorial illustrations, whether allegorical, idealistic or purely botanical, will be accentuated by the introduction of the human female form – the beau ideal.

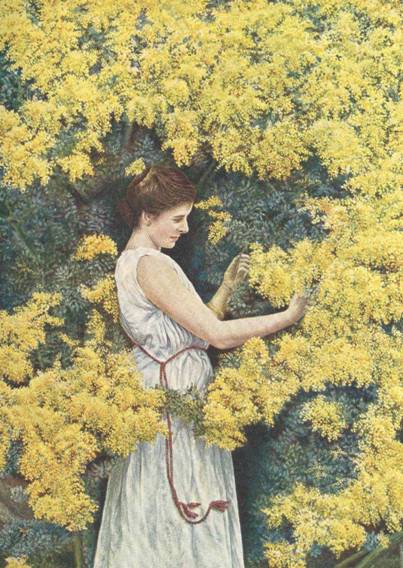

Figure 2: Photograph by A J Campbell of a woman in front of an Acacia longifolia

In this interesting passage AJ commences by telling his readers that his case for the wattle is not in relation to its merits in economic terms. It is a significant departure from what had been the prevailing Australian views in the 19 th and early 20 th centuries about the ‘value’ of wattles. Here, although not uniquely of course, AJ puts the case for the wattle, on aesthetic grounds alone.

But perhaps of greater interest to students of pictorial and photographic history in Australia, is his bold assertion that the tale he is telling of nature and its promotion will be enhanced by the insertion with the text of representations of the human female form. He has already alerted his readers to the association he has made between nature and the feminine. Now he brings his idea that the ‘femaleness’ of nature as seen in September, will be enhanced by the inclusion of photographs. Most other texts, especially botanic accounts of wattles, had never taken the step of locating in such a central place along with the text, the human figure, especially the female. Sometimes, a figure, usually male, might be introduced in natural landscape photographs, but usually it would seem these were designed to give a sense of spatial perspective. Contemporary reviewers were not always convinced of the merits of the inclusion of the female figure. An Argus reviewer wrote on 10 September 1921:

For idealistic purposes Mr Campbell has introduced a figure in most of his pictures, but the idealism is often lost in too obvious pose and manifest self-consciousness. It has unquestionably helped some of the pictures, such as the ‘Cootamundra’ frontispiece, ‘Blackwood’, ‘Coastal Wattle’, ‘Lightwood’ and a few others, but in many instances, the ideal has rather spoiled the actual.

A month-by-month account of Australian wattles

Of wattles in July, AJ writes that the most conspicuous wattle about Melbourne and suburbs is the Cootamundra, Acacia baileyana, introduced from New South Wales . Campbell discusses both names: Cootamundra – after its locality, and Acacia baileyana, so named by von Mueller for its ‘discoverer’, F H Bailey, Government Botanist of Queensland. He comments:

When the Baileyana begins to wane, the Silver Wattles of South Eastern Australia and Tasmania come into bloom. By the end of August the majority are prime, waiting to welcome ‘Yellow-haired September’.

Of the wattle called silver ‘perhaps because of the silvery appearance of its feathery foliage’, he also writes about its place:

For a typical scene of Silver Wattles take our ‘ Home River ‘, the Yarra Yarra, say from Heidelberg to Eltham, including the lower Plenty River . In bend succeeding bend behold the yellow-laden trees, like curtains of screening the stream, some of the flowering tassels kissing the water on one side, and others bending over beds of pennyroyal and maidenhair fern on the land side of the tree. Again, from some contiguous hill or other coign of vantage, gaze on a huge letter ‘S’ which the river lined with yellow has carved in the living green landscape, while the whole locality is suffused with the most delicate of Wattle perfume’.

He then speaks of the Acacia normalis or green wattle, before the first of his most direct paragraphs in the book in the praise of the colour yellow:

What shall we say of the most excellent beauty of Wattle flowers – the clusters of tiny circlets! Curves and circles in art and nature are synonymous with grace and continuity of form: and what of their matchless yellow, before which the colour of the pure gold of Ophir pales! A botanist and scientist has stated: ‘No flowers are more effective than yellow ones’. The yellow in the solar spectrum is the only one that stimulates the Wattles. How wonderful to think that if there were no yellow ray in sunlight all plant life would perish. The auroreal colour if the Gates of Day, and the effulgent glory of the Halls of Sunset, are they not mostly yellow? Still a higher thought, even far ‘above the stars of God’ – may not yellow be the prevailing tint of the ‘Eternal Habitations’? ‘And the City was pure gold, like unto clear glass’.

Here in language, sometimes a bit rich for our latter-day down-to-earth tastes, AJ writes movingly in praise of the yellow, and the question still arises, why do we as Australians, settlers in this land, seem to find such beauty in the yellow of nature as expressed through fine wattle bloom? AJ moves on to discuss September and Acaciapycnantha or Golden wattles. He talks of his earliest reminiscences of Golden Wattle, ‘the nodding yellow plumes, which seemed to beckon me, of slender saplings that grew in the dear old box forest’ at the base of Mt Cotterall, close to his early boyhood home. He then mentions how he was searching alone for wattle, and he says that, sometimes, one likes to ‘hive one’s self with Nature – she often reveals more of her secrets when wooed alone’. There is thus a very distinct identification of nature and wattles with the feminine in a way that in today’s world we may not.

He speaks then of the Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon – and indeed mentions its beautiful quality for furniture. This is followed by the Acacia longifolia or Coastal wattle that may be said to celebrate most enthusiastically, ‘Yellow-haired September’. AJ again emphasises ‘yellow’:

What a priceless colour is yellow! It is stated that no shade has such a sedative influence for good on the sick mind as yellow – be it yellow wall paper, or yellow furnishings, or yellow flowers. Milton, in his Paradise Lost stated that ‘Celestial rosy red’ is ‘love’s proper hue’. But if love could be materialised, it would probably be found yellow- chains of gold of varying thickness, from a thread to a ship’s cable – according to your complaint. Again, does not that nation of great antiquity – the Chinese – call yellow, ‘The Goddess of Light” and is not yellow the sunshine of every flower-scape and the most brilliant colour of the rainbow?’

Two of Kendall’s poems, ‘September in Australia ‘ and ‘Bellbirds’ are again invoked:

When gales of wind and wet dishevel and despoil the fair locks of ‘Yellow- haired September’ the ‘Breath of Nature’ still lends a touch of colour to the land, and onward comes, as the poet (Kendall) sings, ‘October the Maiden of bright yellow tresses.’

This association of spring and nature with the feminine is something our era may not always emphasise despite the long traditions of this throughout history. Yet we should not forget that the early period of twentieth century saw, as did much English poetry, the identification with the feminine of nature. In the Australian case, the ‘harshness of the bush’ had given way to the appreciation of nature by suburban dwellers of nature as a gentle female entity, spearheaded by poets such as Henry Kendall. Take, for example, these passages from the book, An Austral Garden of Verse, published about 1920, as the first school anthology of Australian verse. The editors drew attention to the ‘two phases of our national life’. In the first, ‘The Pioneer found himself face to face with Nature looming stern, inscrutable, seemingly niggardly.’ Then the later phase, of which I would suggest my grandfather’s generation is represented, as a ‘reappraisal of nature’, but one where:

Conditions of living have improved and the outlook on nature has undergone a transformation. The undoubted beauty of Australian scenery, the glory of the clear sunshine, the witchery of birdsong from fern-embowered creeks have burst have burst with all their splendour on the poet minds of the day, and a new note in Australian literature is steadily increasing in volume.8

Come October, AJ notes, Acacia saligna exudes perfume that is somewhat overpowering if taken into a room. Then hail to November and Acacia mollis (Black wattle). Here he describes wattles in the You Yang ranges near where he grew up in Victoria in the 1860s: ‘where the ‘hills and hollows are fairly flushed with its pale or Naples-yellow blossoms’. December brings Frosty wattle or Acacia pruinosa into bloom. Then there is new year’s wattle or Acacia elata . AJ mentions a ‘handsome pair of such wattles at the Botanic Gardens, Melbourne guarding the Lodge by the entrance leading from Millswyn St’ – now long gone.

In ‘Fiery February’, the Acacia implexa, or Lightwood reigns. Acacia maideni that blooms in March comes next, followed by the autumnal wattles, Sunshine wattle or Acaciadiscolor with a picture of my father as a very young child, the only male figure to accompany a wattle. The book finishes with references to June and Acacia suaveolens and a few hurrahs for the Empire wattle, or Queensland silver wattle, and returns to the references from the poems of Kendall, about September, ‘September the splendid, my song hath no music to mingle with thine, and its burden is ended’. But even here he adds a postscript to refer to the Weeping Myall, a wattle-lovers’ tribute with an Acaciamacradenia – to the sons of ‘old wattle who fell in the Great War. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.‘9

Archibald George Campbell (1880 – 1954)

It would be remiss not to mention the work of AJ’s son, Archibald George, (1880-1954). In much of his endeavours in relation to ornithology, promotion of the wattle as Australian floral emblem and in nature conservation, Archibald George played a major role. Unlike his father, he did receive further education, including a period as a student at the School of Horticulture, Burnley, in Victoria in 1895-98. He became an orchardist at Pomonal, but more importantly in 1913 was his purchase at Kilsyth of a property at which he planted over 300 varieties of wattles. He maintained the Wattle League activities, until the demise of the organisation in the 1950s. Much time was spent on conservation issues, including in relation to Mt Buffalo area. His papers are held at the Museum of Victoria . In many ways, it is possible to suggest that son and father shared common interests and that Archibald George’s establishment of the Kilsyth wattle gardens played a key role in his father’s thinking through and explorations of the suitability of the wattle as national emblem.

‘September the splendid’ or ‘a tree for all seasons’?

Nearly one hundred years since AJ delivered his 1908 lecture: ‘with optical lantern views’, we are in a digital age, but still exploring the allusions, the colours, the tints and the tones, of the Australian wattle. Yet as AJ’s own lecture states, whilst he focused on what I would call the ‘September-ness’ of wattle time, the book he produced from that lecture, also lends support to the view implicit in his writings that the wattle is a tree for all seasons. I think that I can do no better than agree with the anonymous 1921Melbourne Herald reviewer of AJ’s ‘multimedia production’ about wattles that:

.the wattle needs no advertisement. It is the shining glory of our hills and streams. It pours out its richest treasures of gold when other flowers are hidden. It redeems the wilderness and illuminates the breaks between the barren scrub. Floods will not drown it and fire will not destroy it. After the forest fires have raged the wattle seeds germinate more freely than ever. When neglected it flourishes, and yet it takes kindly to cultivation, being seen in almost every public park in the land. It has been justly likened to apples of silver in baskets of gold. The prophets and poets have been searching for epithets to adequately describe its billows of yellow bloom. It expresses all moods. There is the silver wattle for gladness and weeping wattle for grief. The happy may rejoice in its effulgent splendour and the bereaved find solace in its tender grace.

Figure 3: Photograph by A J Campbell of a woman amidst the blooms of a Cootamundra wattle Acacia baileyana

These days, new links and associations come to mind. At the local level, I am aware of the activities as diverse as those undertaken by the Hurstbridge Wattle Festival, the work of the Eltham Anglican Church and other religious groups, in drawing in Aboriginal perspectives and most importantly, there is the work of the descendants of William Barak, a proud Kulin man who returned to his Dreaming ‘when the wattles were blooming along the Yarra Yarra’ in 1903. Let us all continue to reflect upon and learn from our Australian environment, especially through the writings and explorations of all those who have gone before – be they those like my grandfather, a first generation settler who grew up near the Werribee River, or the generations of botanists or indeed all who have fostered an interest in the cultivation of our Australian plants, including Indigenous Australians with unique perspectives on the ways of the environment, and recent settlers from the four corners of the globe with new ideas to share. I am pleased to have the opportunity to share with you some of the ideas and photographic images that my grandfather gave us – of that ‘yellow haired lass’, that September, that he celebrated so finely and so eloquently those many years ago.

Ian Campbell is a poet and an Indonesian scholar, when he is not researching his family’s history.

FOOTNOTES

1. This paper is based on a talk presented at the ‘Acacia 2006 Conference’, hosted by the Australian Plants Society Maroondah, at Ringwood, Victoria on 26 August 2006, as part of the 6 th Biennial FJC Rodgers Seminar, sponsored by Australian Plants Society Victoria Incorporated and the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne. The author gratefully acknowledges the roles of the National Library of Australia and the Australian National Botanic Gardens in the conservation of papers, pictorial images and other ephemera relating to the life and work of his late grandfather, AJ Campbell.

2. This reference to 1899 probably refers to his leading these nature excursions in September 1899 to the Werribee Gorge area, but it also may refer to his planting earlier that same year of wattles at a family gravesite near Mt Cotterall, near the Werribee River .

3.Libby Robin’s paper ‘Nationalising nature’ is also linked to the World Wide Wattle site, prepared by Bruce Maslin and Tony Orchard with the support of the Wattle Day Association and the Australian National Botanic Garden at: http://www.worldwidewattle.com/infogallery/symbolic/wattleday.php Robin’s paper is at http://cres.anu.edu.au/people/wattle-day.pdf

4.AJ Campbell was buried at St Kilda General Cemetery, Melbourne .

5. See also Diana Giese ‘Wild places and advancing science’, NLA Newsletter, November 2003, online at: http://www.nla.gov.au/pub/nlanews/2003/nov03/article2.html

6/Allan McEvey, ‘Archibald James Campbell (1853-1929)’, in Bede Nairn and Geoffrey Serle (eds), Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1979, 543-4, online:http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A070546b.htm

7.The number of Acacias has grown significantly since this early twentieth century estimate – even after the recent division of the genera into five, Australia has over 900 Acacias.

8. MP Hansen and D McLachlan (ed.) An Austral garden: An anthology of Australian verse, Melbourne : George Robertson and Co., (no date), p. vi.

9.These last references are understandable given the Great War had only ended two years before the book was published. Also, one of AJ’s sons, Charles, had been severely wounded in the Anzac landing on 25 April 1915. The Latin means ‘ It is sweet and right to die for your country’ and comes from a poem by Wilfred Owen, a leading poet of the First World War.

REFERENCES

Unpublished:

Campbell , AJ Archives: MS 9650, Photographs PIC 7586 , National Library of Australia , Canberra

Campbell , AJ Archives Australian National Botanical Gardens , Canberra

Campbell, AJ Archives: Ornithology section, Museum of Victoria , Melbourne

Campbell, AG Archives: Ornithology section, Museum of Victoria , Melbourne

Published:

Campbell , AJ Golden wattle, our national floral emblem , Melbourne : Osboldstone, 1921.

Campbell , AJ Nests and eggs of Australian birds including the geographical distribution of the species and popular observations thereon , Sheffield : Pawson & Brailsford (for AJ Campbell), 1900 and 1901.

Giese, Diana ‘Wild places and advancing science’, NLA Newsletter, Vol. XIV No. 2 November 2003, online at: http://www.nla.gov.au/pub/nlanews/2003/nov03/article2.html

Griffiths , Tom Forests of ash: an environmental history , Melbourne : Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Griffiths, Tom Hunters and collectors: The antiquarian imagination in Australia , Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Hansen, MP and McLachlan, D (ed.) An Austral garden: An anthology of Australian verse, Melbourne : George Robertson and Co., (no date).

McEvey, Allan ‘Archibald James Campbell (1853-1929)’, in Bede Nairn and Geoffrey Serle (eds), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 7, Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1979, 543-4, and online: http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A070546b.htm

Robin, Libby The flight of the emu: A hundred years of Australian ornithology 1901-2001 , Carlton : Melbourne University Press, 2001.

Robin, Libby How a continent created a nation, Sydney : UNSW Press (in press, 2007).

Robin, Libby ‘Nationalising nature’, Journal of Australian Studies , 73, 2002: 13-26; 219-23.

World Wide Wattle http://www.worldwidewattle.com/infogallery/symbolic/wattleday.php