by Christine Williams

© all rights reserved

(The following article is the basis for a chapter in Green Power: Environmentalists who have changed the face of Australia published by Lothian/Hachette Livre. The book this year won a National Trust of Australia (NSW) Cultural Heritage Award).

From his earliest painting in the 1930s, artist Albert Namatjira set the foundation for a flowering of the Western Desert art that would arrive forty years later. Namatjira’s reputation had become a household name by the 1950s, exerting a major influence on how Australians came to appreciate their great desert island continent. But soon enough he was overlooked as a ‘one-off wonder’ – until an indigenous art movement was reborn at Papunya in the 1970s. The pity of Namatjira’s life was never being fully accepted into white society, which caused the exploitation of his genius and his family’s suffering which continues to this day.

Mid-20th century, artist Albert Namatjira was able to bring into the lounge rooms of capital city dwellers the evocative landscape of Central Australia through the canny depiction of his sacred country. He paid close attention to composition and space and played with an inspired understanding of light and shade to mask the telling of his sacred story of place for the uninitiated. But by the 1950s despite being the darling of the Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney art scenes – while his works were commanding sell-out prices – Namatjira was still the target of deeply-entrenched racist government policies, which prevented all indigenous people from owning land.

Namatjira was born in 1902 at Hermannsburg, a Lutheran mission in Central Australia about 100 kilometres west of Alice Springs (Mparntwe), on the traditional land of the Western Aranda (now administered by Ntaria Council).

It’s been reported that Namatjira had received only two months tuition in painting, when the watercolourist Rex Battarbee visited his desert country in 1936. Art critics have marvelled at the way Namatjira took to painting with such drive and skill, that he “seized on the first methods and medium that came his way . to sing the song of his country” (Amadio 1986, p.2). The story is almost that miraculous. Namatjira did take painting lessons with Battarbee, re-enacted in a film made in 1947 in which Namatjira played himself, no longer a ‘camel boy’ but a confident, celebrated artist (Mountford 1947).

Perhaps it was decided that the film’s story line needed to be simple and clear in showing only Battarbee’s influence on Namatjira. But for a more complete picture it needs to be acknowledged – without diminishing in any way a recognition of Namatjira’s great talent as an artist – that several other painters as well as the remarkable anthropologist, TGH Strehlow, no doubt also had impacts on Namatjira’s development as a ‘European’ artist.

Records held by the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs (Mparntwe) show that from very early on the anthropologist was impressed by Namatjira’s artworks. The two men were born just six years apart at the Hermannsburg Mission1, in the first years of the 20th century. Strehlow’s father was the Lutheran pastor in residence there, and the boy’s earliest years were spent playing with the Aranda children at the mission. In 1922 Strehlow left to study English literature and linguistics at Adelaide University but he returned to the mission after graduation in 1932. Already he saw his “life’s work” connected with the traditional knowledge of indigenous people. “I want to learn all I can from the old men. They’re the ones with secrets locked in their brains,” was Strehlow’s description of the cultural values he knew were hidden from and so unappreciated by Europeans (McNally 1981 p 36).

As a boy Namatjira is said to have lived in the boys’ dormitory at the mission, and been quiet and very sensible.2 He learnt English and became skilled in the range of tasks needed at an outback station, such as carpentry, leatherwork, animal handling and stock work.

From 1928 on, several radical women artists made excursions to the Centre. There’s evidence that the artist Jessie Traill had an exhibition in Alice Springs (Mparntwe) as early as 1928. Then in 1932, Una Teague, the sister of the internationally-recognised artist from Melbourne, Violet Teague, travelled with Jessie Traill to Hermannsburg. A photograph shows Albert Namatjira with two camels in his role as guide for Jessie and Una on a painting trip to Palm Valley . The following year Violet undertook the trip with Una from Melbourne to Hermannsburg in a rented Studebaker complete with driver, camping along the way. Teague was so shocked by the drought conditions around Hermannsburg that she organised a charity art exhibition and about two thousand pounds was raised to construct a water scheme. Namatjira is said to have decorated a boomerang in pokerwork depicting the scene of men at work laying water pipes. He had been crafting pokerwork designs on mulga plaques, coat hangers and boomerangs for some years, receiving the first payment for his art in 1932 (Hoorn 1999: pp.99, 102,103).

It’s been argued that it was Jessie Trail and Violet Teague who provided the initial examples of first-hand European art as a “primary influence on Albert on his path as a Western painter”. An indication of Namatjira’s admiration for Violet is to be found in his naming one of his children after her (Hoorn 1999: pp.99, 102,103).

Another artist, Arthur Murch, travelled twice to Hermannsburg in 1933. At 31, he was the same age as Namatjira and although there’s no published evidence of their meeting, Murch was very interested in the arts and crafts of the Mission community and is said to have “shared his artistic activities with the Aboriginal people” (Murch 1997: pp.51, 119).

1932 was also the year that the watercolourist, Rex Battarbee visited Hermannsburg on a Central Australian trip but he is said not to have met Namatjira who was working elsewhere. The artist Arthur Murch is also believed to have visited Hermannsburg in 1933, and may have met Namatjira. Strehlow recalls the Aranda watching Murch and other painters “intently and with evident fascination” (1951: p.6).3

Then in 1934 Battarbee returned, and Namatjira is reported to have shown an interest in painting, which Battarbee encouraged.

In 1935 Namatjira created what he later said was his first watercolour, ‘The Fleeing Kangaroo’, which he gave to a Lutheran Mission administrator. Meanwhile he had a growing family – a wife and eight children – for which he had to trade physical labour for food, clothing, shelter and lessons at the Mission school.

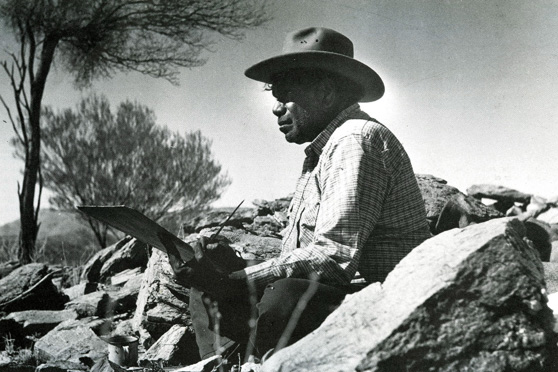

Battarbee returned to Hermannsburg in 1936 and Namatjira worked as his camel ‘boy’ (although a man now aged 34) in return for painting lessons. A photograph taken of Namatjira and Brackenreg near Chewings Range twenty years later shows Namatjira holding a painting across his chest, with Brackenreg tenderly, perhaps even gingerly, touching one corner and a side of the picture. Another press photograph published in 1958 shows Namatjira standing out in the open with white artist Leonard Long, again with Namatjira holding one of his watercolours in front of him (Jones 1986 p.19).4 These were undoubtedly not the first occasions Namatjira had posed for the camera – and perhaps it’s indicative of the way he would have been asked many times to verify a painting’s provenance, now a regular practice required of indigenous artists. There’s something reminiscent of the ‘King Billy’ brass plates that Aboriginal leaders in the nineteenth century wore as a badge of identification through assimilation – obliging their European oppressors who could not pronounce or remember their indigenous names. To view an artist who creates body art on canvas holding his creation in front of his own body causes a resonance of recognition of the imposition of European values – the transfer of art into a commercial ‘hangable’ form – on indigenous cultural creativity. At least the painters can feel a pride in the exhibition of their indigenous identity rather than in displaying a metal plate announcing an inferior and laughable European name.

In those first few years of Namatjira’s painting he would sign his works with a simple ‘Albert’, the name he was christened when he was three years old. Individual creation or possession of an art work is an alien concept to Australian indigenous people, while materialist Western society needs to know the author of a work so that its value can be commoditised as part of the market economy. Recognising this, from about the time of his first solo exhibition in Melbourne in 1938, Albert took a second name, that of his father ‘Namatjira’, and thereafter he carried in this name and identity conflicting European and indigenous cultural values.5

Namatjira gained phenomenal success as an artist, paving the way for recognition of later indigenous artists beyond the blinkered cultural view, which caused personal suffering during his lifetime. Throughout the 1940s Namatjira became increasingly well-known, treated by the media as a figure of endearment and pride. For example in 1946 thirty-six of his forty-one works in a solo exhibition in Adelaide were sold within half an hour of opening, at respectable prices of up to forty guineas each. But his health suffered from grief over several deaths in his family, as well as white-man’s food and entrenched government racism. In 1949 and 1950 applications he made for a grazing lease were rejected and in 1951 he was even denied ownership of a house and land in Darwin on the grounds on his aboriginality – overt racism dressed up as paternalism.

In 1954 Namatjira was presented to Queen Elizabeth in Sydney and was the centre of press and social attention at an exhibition of his work at the Anthony Hordern Gallery. Two years later he was arrested in Alice Springs (Mparntwe) on a charge of drinking alcohol, since this white-man’s drug was officially forbidden to indigenous people. The charge was dismissed but the episode was demeaning.

Finally Natmatjira came of age in European terms. In 1957 he and his wife, Rubina, were granted full citizenship, which allowed them the right to vote, and the freedom to buy and drink alcohol, among other rights, which were denied indigenous people until a referendum in 1967 granted full citizenship to all Australian Aborigines.

Namatjira’s life was certainly damaged by the special status – both revered and scorned – that became his lot as a gifted painter living under a racist government. In 1958 he was charged with supplying alcohol to indigenous people at Morris Soak, where a young woman had been murdered by her husband, and he was sentenced to at first six, later reduced to three, months gaol. With the press across the country carrying pleas for Namatjira’s release, the Federal Minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, intervened so that the great artist could serve his sentence at Papunya. Finally he served just two months due to good behaviour but it’s said he suffered deep depression as he’d hoped for a full remission of the sentence.

Namatjira lost his will to paint. He moved to Hermannsburg and then returned with Rubina to Papunya where he suffered a heart attack in 1959. Namatjira died in hospital in Alice Springs (Mparntwe) and it was reported in the press that “he was interred in the parched red earth of the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) cemetery less than 24 hours after he died”.6 About a hundred of Albert Namatjira’s kin from Finke River and Hermannsburg attended the burial, conducted by his friend, the Lutheran Pastor Albrecht.

Since his death Namatjira’s works have catapulted in price, selling for up to several hundred thousand dollars today. In 2003 a controversy arose when it was discovered that copyright of his works was sold to his former art agent, John Brackenreg of Legend Press, by the Northern Territory public trustee twenty years earlier for $8,500. Copyright is due to expire in 2009. A grandson, Kevin Namatjira, told ABC TV, “We’re sorry for our grandfather, you know. We don’t get that money from our grandfather’s painting or that painting. We don’t get them” (7.30 Report 2003).

So much of Namatjira’s art can now be partially understood through our later knowledge of indigenous art being bound inextricably with indigenous artists’ reverence for the earth. He used recurring motifs – a ghost gum or another stately tree in the foreground, and an escarpment such as Ormiston Gorge or ranges in the background – to tell his story of humans’ links with the spirit of the land. His vibrant use of colour, such as purples and reds, many Europeans viewed as an exaggeration. And his fluent toning and shadowing demonstrated his appreciation of how the light of Central Australia could darken or lighten that spirit of place.

Namatjira was a forerunner in the education of white Australians about the deep spiritual connection between people and the land, a sacred wisdom tradition given him by his forebears and represented through his landscape painting. This expression of hidden knowledge was extended in the late 20th century by such notable indigenous artists as Rover Thomas, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula, Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Ada Bird, Gloria and Kathleen Petyarre, Tommy Watson and others, now recognised on the international art market.

Dr HC (Nugget) Coombs described Albert Namatjira as an artist of genuine creativity whose work “embodied the love of, and identification with, the land”, a quality “shared by Aborigines who have been able to maintain their links with it” (1986 p.vii). Coombs saw Namatjira as “no isolated accident in Aboriginal contemporary history”, in enriching Australian life and its culture (1986: p.vii). Writer Colin Simpson had said something similar back in 1950: “Albert Namatjira is a signpost on the road to a new understanding by us of the capacities of the aboriginal Australian”.7 But Coombs went further. He believed that the interaction between the European and Australian indigenous artistic traditions could produce “a renaissance potentially as significant for Australian life as that which was launched upon Europe by the spread of ‘new knowledge’ from Constantinople in the sixteenth century” (1986: p.vii).

This image of a renaissance is consistent with an artwork by Rover Thomas, Cyclone Tracy, painted in 1991. The piece is emblematic of Aboriginal elders in the Kimberley interpreting the destructive cyclone that hit Darwin – seen as a centre of European culture – as “an ancestral Rainbow Serpent warning Aboriginal people to keep their culture strong”. According to art curator, Wally Caruana, “As a consequence, a renascence of ritual activity occurred to show all people the resilience of Aboriginal culture” (1998: p.3).

The renaissance was already beginning in the early 1970s when Geoffrey Bardon arrived to teach in the government settlement of Papunya, over 100 kilometres west of Hermannsburg. Bardon explained in a documentary that he “never set out to rock any boat, but it seemed silly to have the Aboriginal children sitting there drawing cowboys and Indians all day when they had a perfectly intact culture of their own” (McKenzie). A number of adult indigenous artists “seized the opportunity presented by Bardon’s support and enthusiasm to reveal their deeply and tenaciously held cultural beliefs” in the form of “patterns traced in the sand, sketches on scrap paper and the majestic Honey Ant Mural [which] culminated in a profusion of wondrous paintings” (Perkins 2004 p.vii).

As Bardon explains the scene:

“It was then, after February 1972, that the incredible vitality of the Western Desert art became a veritable flood of brilliant paintings; the men in groups about the darkened, cave-like interior of the galvanised iron circle of a shed, singing and roaring out to their creations and attaining a confraternity of four tribes; forms irradiating into new forms, and conceptions of place and subject matters being set down definitively, technical problems with many of the Pintupi being overcome, and everywhere in the room completed and uncompleted paintings of immense accomplishment.” (Bardon 2004 p.29)

Bardon realised that the ideogrammatic and pictographic texts in Western Desert art were not viewed lineally but multi-directionally (Bardon pp.xx11, and that the work of Keith Namatjira (following Albert Namatjira and other water-colourists of his school), although seeming to accommodate the Western European idea of visual focus or perspective, “seemed to me in part to be a writing of objects non-visually” (Bardon 2004 p.41).

They almost always depicted a scene or involvement of shapes from a position above the depicted earth, this seeming to allow them to write their apparently realistic forms. Yet at the same time they used an emphatic line as assuredly as the traditional painters to delineate Ancestor Beings as pictograms and ideograms . Namatjira and his water-colourist colleagues shared the same cultural traditions as those Western Desert painters of my experience, and felt no need to read a painting from right to left or from a standing position with the painting conventionally presented upon a wall. A painting was read from any direction, as if it were lying upon the earth and able to be walked about . these Western Desert peoples were masterly in their ability to state by indirection or disguise . (Bardon 2004 p.41).

One of the main reasons for disguise was to keep hidden powerful, secret, sexual and sacred beliefs concerned with creation, procreation, and cultural generation. As Bardon observed on arrival at Papunya in 1971, of the four tribal groups brought together there, the Aranda had been ‘detribalised’ and “soured” at the Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission, and that “the white man had made them earn a discontent and misery, for they had learned all the whitefella-ways, and about money, and how something or someone did not have any full worth or place because of money and other concerns” (Bardon 2004 p.7).

Albert Namatjira, being an early product of the effects of white culture superimposed on other ways of knowing and seeing, had despite the hardship, been able to carry his knowledge across to lineally-focussed painting, whereas so many Aranda people must have felt alienated at being misunderstood. Strehlow had already observed since the 1930s this same habit or capacity of traditional Aranda artists for “looking down upon a landscape from above and not from the side, as we do” and noted that this “limited the vision of the artist and frustrated his endeavours to express himself with freedom and clarity” – at least in the context of the acceptance of Europeanised male art as a superior form to be attained (Strehlow 1951: pp.3,5).

Bardon also observed that traditional sand mosaics were group art, and that painters often owned only part of a subject or story, remaining strictly within their own totems or signs (Bardon 2004 p.11, 31). He was able to use this observation to advantage in encouraging the artists in group work.

Albert Namatjira had been an exceptional forerunner of a great artistic energy and sense of beauty that was latent among the Aranda. Strehlow wrote that in his best paintings Namatjira had “put on record the beauty and the colour of Central Australia with a warmth that proclaims his deep love for his homeland” (Strehlow 1951 p.6). But Namatjira’s influence was not restricted to Central Australian Western Desert art. At least one of the leading Arnhem Land artists, Ginger Riley Mundiwalawala, as a young stockman had met Namatjira, the meeting said to be a turning point in the life of the artist-to-be (Kemerre Perkins 2004, p.15). Art curator, Hetti Kemerre Perkins maintains that Albert Namatjira also provided a “profound influence on the first generation of Papunya painters, who saw in his example a way out of the poverty cycle of fringe dweller existence” (2004 p.15).

Although poverty persists, money is flowing into and being distributed throughout indigenous desert community settlements, despatched from sales of Australian indigenous art around the world. For instance, a prestige showcase for art in Europe, the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, last year officially opened its exhibition space to selected Australian aboriginal artists showing Aboriginal culture as “vibrant and dynamic, ageless and contemporary”.8 This might be said to be a long way down the track from the limits placed on Albert Namatjira in 1940 to “restrict himself to fifty watercolours a year” with “prices . fixed between three and fifteen guineas” (Mackenzie 2000).

The cruel irony is that the size of the Australian indigenous art industry is now estimated at far beyond $100 million a year (Owens 2005 p.20). We might pause to give thanks that our powerful red earth has been represented so respectfully by all the environmentalist indigenous desert painters – with Albert Namatjira acknowledged as first among a great history of equals.

Christine Williams is the author of four biographical works. She has won the NSW Ministry for the Arts History Fellowship and is currently Writer in Residence at Hyatt Regency Coolum. Christine was recently selected for a 2008 Asialink residency in India, following publication of a biography, Jiddu Krishnamurti: World Philosopher.

FOOTNOTES

1. Albert’s birth was registered in July 1902 and Strehlow was born in 1908.

2. Strehlow gave this description in a letter to author Joyce Batty on 14 March 1961. He said that when Albert was about fourteen he went “somewhere out bush” to pass his manhood rites for probably about six months. Letter held by Strehlow Research Centre.

3. Strehlow refers to Murch, Battarbee, Gardner and Rowell as painters ushering in a new era by “translating familiar landscape and familiar native figures on to paper and canvas” even though he gives most credit to Battarbee in assisting the first aboriginal painters while they were “striving to gain technical mastery over their medium” (Strehlow 1951 p.7).

4. Sun Herald 17 August 1958 p.19. The article proposes that “a little friendly competition took place between the two artists”, imposing the strong European cultural value of competition on what was more likely to have been a non-competitive, mutually-supportive artistic activity.

5. Andrew Mackenzie says Albert, first named ‘ Elea ‘ by his parents, was of the Kngwarriya kinship group (2000). According to TGH Strehlow, Albert’s totem was a carpet snake since he was born at Palitinja. His father, Namatjira, born near Ormiston Gorge, was a Paltara man, and his mother, Ljukuta, born near Palm Valley, was a Mbitjana woman. Albert married Ilkalita, later christened Rubina, whose father was a Kukatja man.

6.Centralian Advocate 14 August 1959. The article carried a photograph of Albert Namatjira’s widow, Rubina, carrying flowers to the grave. According to the former Director of the Art Gallery of South Australia, Daniel Thomas, Rubina Namatjira returned to Hermannsburg where she lived with her daughter Maisie until her death in 1974, when Rubina, grief-stricken, applied a psychological force and ‘sang’ herself to death within weeks. In 1986 Thomas wrote that she lay in an unmarked grave near Maisie in the Hermannsburg cemetery.

7. The article from an unidentified newspaper dated 12 August 1950 is held by the Strehlow Research Centre. Simpson goes on to deplore intelligence tests, praise the ability of indigenous people to memorise “whole cycles of corroboree songs, long ancestral myths and complex languages” and explain that there is “no significant difference between the sum of innate mental abilities of any racial group”. Although the article is supportive of Namatjira’s talent, it’s an indication that canvassing these racial questions was considered acceptable public debate regardless of how confronting and offensive it must have been to indigenous people. Strehlow too claimed Namatjira had “destroyed the myth of the constitutional incapacity of the Australian native to learn and to apply methods learnt from Europeans” (1951: p.6). In 1966 Strehlow said that thirty years before even the most intelligent aboriginal adults had been “proclaimed by an American professor of psychology to have a mental age of only 12 years or less”, firm beliefs that now seemed “almost antediluvian” (1966: p.2). Address held by Strehlow Research Centre.

8. Quote attributed to MQB Chairman and Managing Director, Stéphane Martin (Owens 2005).

REFERENCES

Amadio, Nadine (ed.) 1986, Albert Namatjira The Life and Work of an Australian Painter Macmillan Melbourne.

Bardon, Geoffrey and Bardon, James 2004 Papunya A Place Made After the Story Miegunyah Press (MUP) Melbourne .

Coombs, H.C. 1986, Introduction Albert Namatjira The Life and Work of an Australian Painter Macmillan Melbourne.

Caruana, Wally 1998, “a tribute: Rover Thomas” artonview winter.

Druce, Felicity & Clark, Jane (eds.) 1999, Violet Teague 1872-1951 Beagle Press Roseville Sydney .

Hoorn, Jeanette 1999 “Hermannsburg” Violet Teague 1872-1951 (Des) Jane Clark and Felicity Druce The Beagle Press Melbourne .

Jones, Jonah 1986 “The Anniversary Exhibition” Albert Namatjira The Life and Work of an Australian Painter Macmillan Melbourne.

McNally, Ward 1981, Aborigines, Arfefacts and Anguish Lutheran Publishing House Adelaide .

Murch, Ria 1997 Arthur Murch An Artist’s Life 1902-1989 Ruskin Rowe Press Avalon Sydney.

Owens, Susan 2005 “Paris Dreaming”. The Australian Financial Review 30 June.

(Kemerra) Perkins, Hetti 2004, Introduction, Tradition Today Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney .

Perkins, Hetti 2004, Foreword, Papunya A Place Made After the Story Miegunyah Press (MUP) Melbourne .

Strehlow, TGH 1951 Foreword Modern Australian Aboriginal Art (Battarbee, Rex) Angus & Robertson London.

Thomas, Daniel 1986 “Albert Namatjira and the Worlds of Art” Albert Namatjira The Life and Work of an Australian Painter Macmillan Melbourne.

PAPER

Strehlow, TGH 1966 “Centralian Art” address at exhibition at Battarbee Centralian Arts, Adelaide Festival of Arts 11 March.

FILM/VIDEO

Namatjira the painter 1947 film Lee Robinson (dir.) Charles Mountford (ass. producer) Commonwealth Department of Information Canberra.

Mr Patterns 2004 documentary Film Australia/ABC Catriona McKenzie (dir.) Sydney .

7.30 Report ABC TV McLaughlin, Murray (prod.) 2003 “Row erupts over copyright of Namatjira’s works” 21 April.

ONLINE

Mackenzie, Andrew 2000 www.artistsfootsteps.com/html/Namatjira_biography.htm accessed 12 August 2005.