by Barry McGowan

© all rights reserved

There have been only a few studies on Chinese agricultural activities in Australia , and even fewer on the technology and physical dimensions of Chinese market gardens. No Australian equivalent exists to the voluminous study by Sucheng Chan, This bittersweet soil: the Chinese in California Agriculture 1860-1910. This is a surprising omission, for Chinese market gardeners were ubiquitous in colonial Australia and for several decades after Federation. As early as 1863 one observer said of Victoria that there was ‘scarcely a town but is now well supplied with all kinds of household vegetables by these celestial gardeners’. Many other contemporary observers made similar observations. In the Northern Territory in the nineteenth century the Chinese had total dominance of all agricultural and market gardening activity.1

The most significant Australian study of Chinese commercial market gardening and other forms of agriculture is Cathie May’s Topsawyers: the Chinese in Cairns 1870 to 1920 , published in 1986. In this work May discussed the dominant role played by the Chinese in the agricultural industry in the Cairns District and their economic and social importance to the region. Her study was not confined to market gardeners, but dealt primarily with the Chinese in other agricultural pursuits, such as corn, sugar and banana growing. The work by Ian Jack and Katie Holmes on Ah Toy’s garden on the Palmer River gold fields in 1984 has a special significance as it was the first archaeological survey in Australia of a Chinese market garden site.2

Several historians, for instance C.Y. Choi, Ann Curthoys and more recently, Michael Williams, have referred to the post-gold rush significance of the occupational shift of the Chinese people from gold mining into pursuits such as market gardening. The next studies of significance were not until 2001, when several articles appeared in Australian Garden History , focusing on market gardens in Melbourne and Sydney. In that year historian and archaeologist, Ian Jack, remarked that there was a ‘rich heritage and history deriving from the Chinese pre-eminence in market gardening and irrigation and that this was in need of urgent synthesis and field work’. He commented critically on the historian’s blind spot for archaeological and material culture.3

Jack’s remarks were reinforced by Warwick Frost, who, in 2002, wrote in critical terms of the characterisation of the Chinese as sojourners rather than settlers and the absence of any detailed consideration of the development of Chinese farming over time and of their technology, methods, labour arrangements and interactions with Europeans. He remarked that the gardeners and many of the farm labourers warrant recognition as pioneers, but very few histories of farming in Australia even mention them. As if in answer to the call, a heritage survey of the Rockdale market garden was undertaken by the NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources in 2003, and an account of the Chinese market gardens at Willoughby in Sydney was completed by Karla Whitmore in 2004.4

The most recent study of Chinese market gardens is by Zvonkica Stanin, published in the Journal of Australian Colonial History in 2005. Her account is based on an archaeological survey of Chinese market gardening activity on the Loddon River near Vaughan in Victoria, part of the Mount Alexander diggings. As only the third archaeological account of a Chinese market garden in Australia , and the most recent one at that, it will stand as a benchmark for some time. In the same issue I referred in some detail to Chinese market gardening activities on the Braidwood goldfields in NSW, and I discuss the physical dimensions of that work further in this article. Keir Reeves also commented in the same issue on Chinese market gardens in the Castlemaine ( Mount Alexander ) area.5

This recent surge of scholarly activity is impressive, but it is still in need of further work. There has been very little discussion on the rich heritage and history of Chinese market gardening in pastoral and arid landscapes. All of the market garden studies have centred on goldfield and urban landscapes, almost wholly along the eastern and south eastern seaboards. The relative absence of work by historians on this subject can be explained to a degree by the paucity of archival records, for market gardening was a tangential area of interest to European observers, perhaps something that was commonplace and deemed as unremarkable, not meriting further comment. Adding to this neglect is the physical invisibility of many of the rural market gardens, for their location is often but a distant memory, the gardeners and their kin having long since departed. The possibility of deriving accounts from descendants in urban areas is much stronger, but in many rural areas the town or pastoral property has long since been abandoned. But the gardens exist and despite the passage of time they are often in surprisingly good condition.

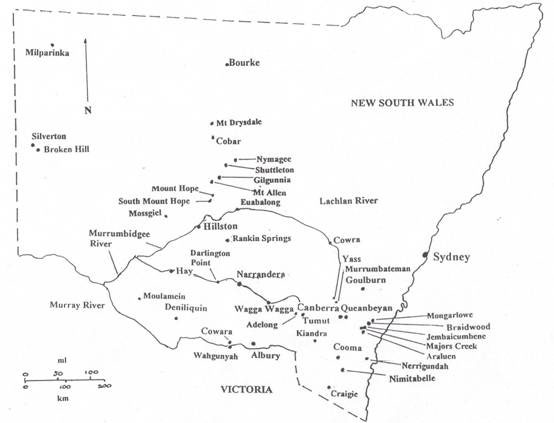

In this paper I discuss Chinese market gardening activities in southern and western NSW, the former defined as the area south of Goulburn and the latter as the Riverina, north to Cobar and Bourke and west towards Broken Hill. Most of the region north and west of the Riverina (and in particular, north and west of Hillston) can be described in most seasons as arid, bordering on desert in the north west of the State. Southern NSW and the Riverina are not regarded normally as arid, though the lack of rainfall over the last few years may suggest otherwise. The market gardens in these areas provide a useful point of contrast with the examples further west and are included for that reason. There are also very strong linkages between the Chinese people in the Riverina and western NSW. In my paper specific themes include the physical characteristics, dimensions and layout of the gardens, methods of working and water retrieval, technological adaptation and race relations. I also address the concept of the gardeners as pioneers, a hypothesis first elaborated upon by Shen Yuanfang in her book Dragon Seed in the Antipodes .6

Fig.1. Market garden sites and other towns and features mentioned in the text

Southern New South Wales

I commence my discussion with the Braidwood goldfields (Araluen, Majors Creek, Jembaicumbene and Mongarlowe), which were amongst the most prosperous and enduring in NSW. The Chinese presence was most marked between 1858 and 1862, but lasted for many decades after. Exact numbers are not available, but from various local reports I have estimated the Chinese population at about 2,000 at peak, although it may have been much higher. The first Chinese gardens were associated with the goldfields. There was occasional mention of the gardens in the contemporary press, but my main sources have been mining lease maps and anecdotal accounts, backed up by field surveys.

The first mention of market gardening was not until 1870. On that occasion it was reported that the Chinese people at Araluen had some fine gardens. Later in 1896 it was commented that on the outskirts of the town some Chinese had ‘cultivated little patches of ground on which they grow potatoes and other vegetables’.7 Unfortunately there is no local memory of these gardens, and the physical remains have probably succumbed to gold dredging. At Jembaicumbene, two undated, but obviously very early, lease maps show an area of Chinese gardens to the west of the main village, with a creek frontage of about 200 metres. The site has been destroyed by subsequent gold dredging.

There were two other gardens at Jembaicumbene, both of which were on pastoral properties and are still visible today. At Glendaurel a dam is located in a gully and the water reticulated to the gardens by a water race. The dam, race, some piping, irrigation channels, mounds and fruit trees are still visible. Farm account books show that the gardens were worked at least as early as 1893 and almost continually between 1899 and 1913 by several Chinese men, for instance, Ah Hing, Ah Yin, Sam Gow, Ah Moon, Ah Kit and James Ahoy and his son and a daughter. This latter period of work coincides with the gold dredging boom at Jembaicumbene in 1899, and suggests that the gardeners were not only supplying the property, but also many of the mining fraternity. The gardeners and other Chinese employees were paid regular wages with rations by the property owners, the Hassall family, and their remuneration was adjusted regularly. At nearby Durham Hall the outlines of the garden, furrows and mounds are still visible. Water was supplied from a nearby stone-lined well.8

At Majors Creek a Chinese garden (there was probably more than one) is located some distance away from the main creek, which was devoted entirely to mining. The garden has a gully frontage of about 150 metres. A dam is located in the gully and the water reticulated to the garden by a water race, which runs along the upper length of the garden. Near the race are several small round pits, which may have served as repositories for night soil. A hut was located near the dam and possibly another one near the race. On the Mongarlowe field a number of small market gardens have been identified from mining lease maps and field surveys.9 A drawing published in the Sydney Illustrated News on 20 January 1870 shows the Mongarlowe ‘joss house’ and a number of Chinese huts just across the river from the main village. It also shows several Chinese crossing the river with merchandise, quite possibly garden produce, on their shoulders.

Fig 2: Chinese Market Garden, Mona, near Braidwood, c. 1900 (Photograph courtesy Ms Kerry Stewart, Canberra )

One of the largest gardens in the district was on ‘Mona’ station just outside Braidwood. This garden helped supply the Braidwood market, and several men worked on it for many years up until the 1930s. Water was drawn from a nearby creek by a water race, which ran along the top of the gardens. The gardens were about 150 metres in length and about 50 metres in width with a creek frontage, and the layout of the gardens into alternate furrows and mounds is very similar to that used in many gardens in China at that time.10 The outline of the garden, the water race and a possible holding dam are still visible today. A rare account of this garden arose from the heavy rains and floods of 1898. On that occasion it was reported that:

enterprising children spent the morning capturing pumpkins and water melons from Ah Chew’s market garden…Ah Chew’s crop for the season was entirely lost. He employed two men on his garden and by the use of intensive labour and irrigation by small hand-dug canals and good gardening practices had been able to supply fresh vegetables for some years to a ready market in the town.11

A further garden in the Braidwood area is located on the slopes of Mount Gillamatong . In this unlikely location the gardeners benefited from a soakage which is still evident today, and the outline of the garden and a hut site are still visible. Some distance from Braidwood is ‘Manar’ station. Preliminary investigations have pointed to an area of cultivation identifiable by evenly spaced furrows and mounds, a fruit tree and possible hut site. Water was carted from a perennial spring which was located several hundred metres away. Clearly in the Braidwood area the Chinese gardeners did not only supply the mining fraternity, but the farm properties and their employees and the neighbouring towns.

There were many other market gardens in the region, but only a few of them were associated with mining. At Queanbeyan there were several market gardens with river frontage either in or near the town; some of the gardeners had worked as miners in the Braidwood District. Market gardens were also located at Yass, Murrumbateman and Goulburn. There were several gardens at Goulburn, one of the largest of which was owned by the Nomchong family, who were also prominent entrepreneurs in the Braidwood District. These gardens were substantial and still in existence in the 1950s.12 In the 1920s and later the water was raised by petrol powered pumps direct from the Mulwaree River . The garden area is still extant, as are the remains of the footings for the pumps, remains of buckets and a large harrow made in the fashion of a windlass and adorned with discarded iron pegs from the nearby railway line. As evident from the illustration, the layout of the garden was very similar to that at Mona near Braidwood.

Fig 3: Chinese Market Garden, Goulburn, c 1900 (Photograph courtesy Ms Rosslyn Maddrell, Braidwood)

Further south at the town of Craigie near Bombala there is also a strong local memory of Chinese involvement in pastoral activities and market gardening. Chinese gardeners in this area were also involved in gold mining, and much of the garden produce was transported to the nearby Delegate and Bendoc goldfields. The site of the gardens is still visible, but other physical evidence, including the Chinese cemetery, has been lost. Chinese market gardeners also existed in perhaps the most unlikely location of all, at Kiandra in the Snowy Mountains.13

More significant perhaps was the involvement of Chinese in tenant farming on the Tumut Plains. Here they were engaged primarily in the growing of tobacco, corn and broom millet as well as market gardening. Fortunately, there are local accounts of these activities, although the garden and farms sites have yet to be surveyed. According to a local resident, Jack Bridle, the farmers carried nine to eighteen litre cans of water on a yoke, watering their plants with a long handled home-made dipper or ladle. As a young man he worked for the Chinese in the 1930s, when he was engaged primarily in cutting and carting wood for the tobacco kilns.14

The Riverina and western New South Wales

In the Riverina and western NSW several thousand Chinese men were employed in land clearing (referred to colloquially as scrub-cutting and ring-barking), market gardening and ancillary activities. The cleared land was used for wheat growing and pastoral activities, in particular, sheep grazing, and the men resided in camps on the fringe of towns and on the pastoral properties. A detailed account of the five largest camps (subsequently referred to as the Brennan report) was prepared in 1883 by Martin Brennan, the NSW Sub-Inspector of Police, and Quong Tart, who was at that time NSW’s leading Chinese entrepreneur and one of the colony’s most respected citizens. The total Chinese population in the five largest camps was 869. In order of significance these camps were located at Narrandera, Wagga Wagga, Deniliquin, Hay and Albury.15

The Brennan Report was prompted by a number of concerns, not least of which was the perceived prevalence of opium smoking and the poor state of hygiene, but it provides a rare glimpse of life in the camps and is invaluable for that reason. At Narrandera, the land was held under lease by two Chinese men, who in turn sub-let the land to other Chinese. There were 340 people at the camp, of whom 12 were gardeners, 124 were labourers, and 64 were cooks, store keepers, owners of gambling or opium houses and other related occupations.. At some periods the population was much larger when the men returned from their contract work on the pastoral properties. The camp was surrounded by a palisade, outside of which were an orchard and several hectares of vegetables. According to historian Bill Gammage most of the camp was owned by Sam Yett.16 The camp site and the outline of the gardens are still visible today. All the buildings have been removed, but some foundations remain.

Chinese camps and ringbarking were not confined to the larger Riverina towns and their immediate environs. For instance, there is a strong local memory of a large Chinese camp on Conapaira station near Rankin Springs well to the north of Narrandera. Water was supplied from a collared well built over a spring. The garden has all the hallmarks of careful Chinese enterprise, with irrigation channels, embankments and a wooden cover for the well. There are two hut sites and a likely blacksmith’s forge nearby. No Chinese artefacts have been found, although this could be explained by subsequent European occupation and the deposition of top soil drift. North of Rankin Springs at Euabalong there were Chinese market gardens and at least one joss house, thus suggesting that there must have been a large camp in that area. There were also camps at the towns of Mossgiel and Darlington Point further west. At Darlington Point the Chinese garden was described as ‘fearfully and wonderfully irrigated’ and a ‘spectacular success’. It was ‘washed by the Murrumbidgee River , watered by two wells, and traversed throughout by canals’.17

A Chinese camp and market gardens were also located on the banks of the Lachlan River at Hillston about 100 km north of Griffith . One of the earliest accounts of these gardens resulted from the aftermath of a riot between the Chinese and Europeans in 1895. On the day following Chinese New Year a number of Europeans visited the garden, known as Chong Lees, which adjoined a camp where 30 or 40 Chinese lived. Another garden, owned by Harry Fong You was located across the river. The visitors were well treated at Chong Lees, but some of the more inebriated began to pull fruit from the trees. No notice was taken of the protestations of the Chinese and a fight ensued. The Europeans were driven from the gardens, both parties being joined by more of their compatriots and clashing on the bridge. About 30 Chinese and 20 Europeans were involved in the brawl. One Chinese man was killed and three severely wounded. Ten Europeans were brought to trial, but they were all acquitted of manslaughter. 18

Another more recent and sedate account of the Hillston gardens can be found in the reminiscences of Tom Parr, who worked in the school holidays in the gardens for four weeks at five shillings per week. He stated that the Chinese raised water from the river by small buckets holding about two litres, which were fastened to an endless chain driven by one horse going round and round continuously. The Chinese farmers flood irrigated some of their vegetables and fruit trees. But much of the water was run down a drain to holes or ponds of about 1350 litres capacity. From there the water was taken to the plants in two large watering cans carried on a shoulder yoke. The method of raising water from the Lachlan River has strong similarities to that described by Franklin King in his 1911 account of farming in China , Korea and Japan , although a treadmill was not used. There is no evidence of these gardens today as the area is now used for commercial orchards by European farmers. Strong anecdotal evidence suggests that Chinese ring-barkers were employed on nearby Roto station. All that remains of an alleged Chinese market garden and camp is a partly collapsed wood-lined well and a possible house site.19

Without scrub-cutting, an extensive and labour-intensive activity, there would have been far fewer Chinese in the region and nowhere near as many gardens. By any measure the amount of cleared land was enormous. For instance, in 1890 the manager of Coan Downs, a property of about 96,000 hectares north of Hillston, remarked that if it had not been for the Chinese labourers the station would never have been cleared, and that as a consequence he had ringbarked more land than any other station in the neighbourhood, increasing the stock carrying capacity enormously. Land clearing work was negotiated between the landowners and Chinese contractors. Food, equipment, other provisions and transport were supplied by Chinese merchants in towns such as Narrandera. Some of the market gardeners would have also worked on the ringbarking contracts, though others were engaged in gardening full time.20

The riots at Hillston are a reminder that racial conflict was not confined to the goldfields. However, this particular incident should possibly be seen more as a one–off occurrence, unusual for a rural town, and one over which the police had little immediate control. Otherwise almost all other incidents that have come to light constitute the usual array of taunts, cowardly assaults and bullying. The assaults were dealt with in the courts, the magistrates and the press often reminding the townspeople that regardless of what they may think of the Chinese as a race, as individuals they were entitled to the same legal protection and penalties as everyone else.21

Racial tensions aside, the Chinese were very highly regarded as market gardeners, an activity in which they were not usually in direct competition with Europeans. The same considerations applied to their employment as scrub cutters and ring-barkers. In 1890 a correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald stated that the Chinese were highly sought after in the latter occupations. It was not so much because they worked for less, for in many cases they got the same wages or even more than European workers; it was because they were regarded as steadier and more reliable. As cooks and gardeners the Chinese were invaluable and they produced nearly all the vegetables grown in the bush. They could also turn their hand to rabbiting and were found ready to do nearly all the rough work on the stations. In Wagga Wagga the Chinese were renowned for their generous contributions to the hospital and local churches, and events such as the opening of the new ‘joss house’ in 1887 and celebration of the Chinese New Year attracted many Europeans.22

Although the topic of race relations in rural Australia is still in need of much research, the general picture beginning to emerge in southern and western NSW on the goldfields and rural districts is predominantly one of tolerance.23 For the rural Chinese support for this scenario can be found in the studies by May and Lancashire . The Chinese in the Cairns District were noted for their lawfulness and generosity in local causes, and were an accepted part of everyday life and individually tolerated. They were not in threatening occupations and served an important economic function in opening up the land. Lancashire’s study of the Chinese vineyard workers in north east Victoria is of particular relevance, as some of these men also worked in the Riverina. The contractual arrangements and economic co-dependence of the Chinese were very similar to those in southern and western NSW. There was very little in the way of strong anti-Chinese sentiment.24

The Chinese were important pioneers in the Riverina and western NSW, with large scale activities and large numbers involved. A Chinese population in the Riverina and adjacent districts can be estimated at about 1,600, combining and extrapolating the information in the Brennan report with that in an 1878 report on the Chinese in NSW. For western NSW as a whole, the numbers were much higher. The ringbarking frontier was moving sharply northwards during the 1880s, prompted in part by a boom in copper mining activity. Cobar was the largest town, but it was closely followed by Nymagee, and at some remove, by South Mount Hope, Mount Hope , Shuttleton and the gold mining settlements at Gilgunnia, Mount Allen , Mount Drysdale and Canbelego. The miners and their families were the market for many of the pastoralists, who needed to clear the land to increase their stock carrying capacity; and everyone needed fresh fruit and vegetables. Chinese market gardeners and ring-barkers were essential to these developments.

Of the above mentioned towns only Cobar is viable now, and Nymagee and Mount Hope are fading fast. All the others are abandoned. Where there were thousands of people now only a few score remain. But it was not always so, for in 1888 Nymagee had a population of about 1,200 Europeans and a large number of Chinese, who were reported as having about a dozen bark houses and huts in the eastern part of the town. They were engaged primarily in scrub cutting and ringbarking, and also had several market gardens.25 The main market garden area at Nymagee is east of the town. It is difficult to obtain an accurate picture of its former size, for the town dam now occupies most of the site. But some fruit trees and the tumbledown and overgrown remains of several huts can be seen. Storm water flows from a nearby gully were channelled into a dam.

Fig 4: Water channel and garden bed, Chinese market garden, Nymagee Station (author’s photograph)

Some 15 km north of the town is Nymagee station, and on it a most remarkable example of a Chinese market garden. It is about 180 m in length and about 60 m wide and bordered by embankments and fences. According to Darby Warner, the current owner, water was reticulated from a nearby soakage and overflow and channelled into the garden by way of a wing dam.26 The remains of the wing dam, the internal channels, collapsed fencing and garden beds are still visible. Of particular note is the orchard, in which there are a large number of fruit trees; figs, quinces and mulberries. Part of the walls and chimney of the gardener’s slab hut are still standing, courtesy of a large, gnarled grape vine.

Two gardens are located between Mount Hope and Nymagee. At the former gold mining town of Gilgunnia the gardens were run by Charley Chin. Water was reticulated by way of a water race from a nearby dam built for the gold crushing battery. The water was stored at the garden in another smaller dam and, according to local accounts, carried to the plants in two large buckets holding between 18 and 27 litres each and suspended on either end of a shoulder yoke.27 Remains of the garden can still be seen today, and include the water race, internal dam, parts of a wooden, iron and wire fence mounted on an embankment surrounding the garden, and two quince trees, barely alive.

Fig 5: Holding Dam, Chinese market garden Gilgunnia. (author’s photograph)

The second market garden is located on Bedooba Station. The remains are prolific and include the dam which was built to capture gully flows, a fruit tree, and an amazing collection of household items such as cast iron stoves, buckets for gathering the fruit and vegetables, and improvised agricultural items, one of which is a single blade plough and seeder. Bedooba is now amalgamated with another property. No one lives there, but according to Barry Betts, the current owner, it once had a large farm population, and the butcher and blacksmith shops are still standing. Chinese market gardens were allegedly located at Mount Hope and on Coan Downs station.

Fig 6: Chinese market garden dam, Bedooba station (author’s photograph)

Further north is the much larger and more resilient mining town of Cobar. Here there were several large Chinese gardens. My information on the Chinese people at Cobar has been gleaned from the reminiscences of a local resident, Alan Delaney, who went to school at Cobar in the 1940s and 50s. According to Alan there were two market gardens. The main one was owned by Mah Mong and existed into the 1940s, until a fire levelled his large two-storey building, which was located at the garden. His garden was located immediately south of the railway line, and is today the site of a housing development spread over several blocks and a motel.

Alan recalled that there were upwards of 500 Chinese in the town, almost all of whom worked for Mah Mong, either on the gardens or as contract labourers on pastoral stations. The siting of the market gardens showed an ingenious use of scarce water resources, for the stormwater flow was captured from several directions, much of it along large eroded gullies on the edge of the roads. During storms the water and silt were channelled into stone and wooden sluice gates, from where they were reticulated into two large dams in the gardens. From the dams the water was pumped into a tall water tower, and from there reticulated into the gardens.

The second garden also utilised storm water flows. It was located at the other end of town, and used storm water from the railway culverts. The water was channelled into two large dams and from there pumped to the gardens and a large tank. Remarkably, part of the gardens, including the two dams, the tank, pipes and remains of the pump can still be seen. This method of water collection is almost identical to that cited by Franklin King. In the more settled parts of China the run-off from the towns was highly valued for its nutrients and ingredients such as soap, which helped flocculate the soil. The same practice may have been used in the more arid areas of China as well, though King did not visit them.28

Other Chinese market gardens are located on Mount Drysdale station, about 34 km north of Cobar, and at Bourke. Mount Drysdale was the site of important gold mining activity in the 1890s and 1930s, which gave rise to two towns, Mount Drysdale and West Drysdale . The Chinese gardens are largely intact, and include the wooden, iron and wire netting fences, a gateway, a pipe which took water from the base of a large mine dam (which they probably built) to a small holding tank sunk in the middle of the garden, irrigation channels and stockyards. There is also an internal enclosure with galvanised iron fencing which may have been a garden or perhaps a holding yard for pigs or poultry. According to the owners of Mount Drysdale , Michael and Shirley Mitchell, several hundred Chinese men were engaged in ringbarking on an adjoining property.

Fig 7: Water channels and garden beds, Chinese market garden, Mt Drysdale (author’s photograph)

At Bourke there was a Chinese camp at Darling Street and several Chinese gardens. A large garden, known locally as the ‘Garden of Eden’, was located near the weir on the Darling River , and there are indications that water was raised and distributed in the same way as at Hillston. In later years petrol pumps were used. The garden was abandoned in the 1920s. There were three other gardens in town, the largest of which covered 2.4 hectares and employed 11 men. Water was obtained by wells and distributed originally by hand; pumps were introduced later. Bourke was one of the few towns in western NSW where there were also European gardeners. Chinese employment agencies and contractors were also engaged in organising ringbarking contracts and employment for cooks and gardeners.29

Market gardens were also located at the mining towns of Broken Hill, Silverton and Milparinka near the South Australian border. At the former locale the garden is located on Clevedale station, about five kilometres east of the town. The embankments for the garden and some internal galvanised fencing similar to that at Mount Drysdale still remain together with two ship’s tanks for storing water, a large boiler and the remains of an abandoned motor vehicle. Water was obtained from a nearby well, now the site of a windmill. At Silverton, the precursor to Broken Hill, the Chinese gardeners were amongst the first business people to arrive in town and by May 1884 had commenced work on the establishment of a garden. 30

Chinese market gardeners also played a very important part in the sustenance of the remote typhoid-stricken gold mining town of Milparinka , located in perhaps the most arid part of New South Wales , and within a short distance from sand hill and gibber country. The gardens were located on the floodplain of Evelyn Creek, which is more often dry than running, and were watered from a 15 metre well.31 In 1881 the Warden commented that the improvement in the general health of the inhabitants was ‘in some degree…attributable to the good supply of vegetables raised by the Chinese gardeners’, of whom there were eight employed on two gardens. The following year he commented that the gardeners had been very successful in supplying vegetables at reasonable prices. They had grown potatoes and the following year they expected to have peaches, pears and grapes in bearing.32

Conclusions

Demographically and economically the Chinese presence in southern and western NSW was significant, and evidence of an important pattern of migration lasting for many decades from the goldfields to rural areas and rural occupations. The primary reason for this migration in the Riverina and western NSW was the opportunity presented by an expansion of pastoralism, itself partly driven in the area north of Hillston by a mineral boom, which lasted for almost forty years. Most Chinese were employed on land clearing contracts; others were engaged in business activities such as commerce and market gardening. The numbers of Chinese engaged in the latter occupation were small compared to those engaged in land clearing, but their gardens were an essential part of town and country life, supplying fresh fruit and vegetables not only to themselves but to pastoral stations, mining communities and other towns. In many instances it would be difficult to contemplate a more forbidding and unfriendly physical environment, but they turned these impediments to advantage. Their perseverance and success surely earns them the long-denied accolade of pioneer.

The market gardens provide an excellent and persuasive example of environmental and technological adaptation. Clearly the Chinese market gardeners were very skilled and innovative workers, and used a variety of techniques to harness the scarce water resources in the arid far west. Perhaps their most innovative technique was the use of storm water flows and soakages. The former technique was in common use in China , and differed from the techniques used in the better watered parts of Australia , for instance in southern NSW. It would appear to have been foreign to most European gardeners. The Chinese gardeners were also innovative and inventive in the manufacture of agricultural implements, all of which would have been assembled on site.

From a heritage viewpoint these gardens are highly significant. That so much should remain – the garden layout, water races, wells, the fruit trees and the equipment – after so long a lapse of time is a remarkable tribute to the ingenuity and perseverance of the Chinese people in such a difficult physical environment. But the gardens are also an endangered landscape and the careless thrust of a bulldozer blade could in minutes destroy what has endured for so long. Finding any garden in Australia that is over 100 years old is remarkable enough, but even more so where the gardens are located in such arid and unforgiving landscapes.

Barry McGowan is a Visiting Fellow at the School of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Australian National University.

Footnotes

1. Sucheng Chan, This Bitter Sweet Soil. The Chinese in California Agriculture, 1860-1910 , (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986); D. Horsfall, March to Big Gold Mountain , (Melbourne: Red Rooster Press, 1985), p.119; Timothy Jones, The Chinese in the Northern Territory , (Darwin: Northern Territory University Press, 1990), p.55.

2. Cathie May, Topsawyers: the Chinese in Cairns 1870 to 1920 , Studies in North Queensland History No.6, (Townsville: History Department, James Cook University, 1984); Michael Williams, Chinese Settlement in NSW. A thematic history , a report for the NSW Heritage Office of NSW, unpublished, (1999); Ian Jack, Kate Holmes,’ Ah Toy’s Garden: a Chinese market garden on the Palmer River Goldfield, North Queensland ‘, Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology , Vol.2, (1984), p.57.

3. C.Y. Choi, Chinese Migration and Settlement in Australia , (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 1975), pp.28-33. Ann Curthoys, ‘Race & Ethnicity: A Study of the response of British colonists to Aborigines, Chinese and non-British Europeans in New South Wales, 1856-1881’, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, (Sydney: Macquarie University, 1973); Colleen Morris, ‘Chinese Market Gardens in Sydney’, Australian Garden History , Vol.12, No.5, (March/April 2001), pp.4-7; Sandra Pullman, ‘Along Melbourne’s rivers and creeks’, pp.9-10; Ian Jack, ‘Some Less Familiar Aspects of the Chinese in 19th-century Australia’, in The Overseas Chinese in Australasia: History, Settlement and Interactions , Henry Chan, Ann Curthoys and Nora Chiang, Monograph 3, (Canberra: National Taiwan University and Australian National University, 2001).

4. Warwick Frost, ‘Migrants and Technological Transfer: Chinese farming in Australia, 1850-1920’, Australian Economic History Review 42, no. 2, (2002), pp.113-131; NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources,Rockdale Market Gardens , Conservation Management Plan, (2003); Karla Whitmore, Willoughby’s Chinese market gardens, unpublished paper, (January, 2004).

5. Zvonka, Stanin, ‘From Li Chun to Yong Kit: A Market Garden on the Loddon, 1851-1912’ Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol.6, (2004), pp.15-34; Barry McGowan, ‘The Chinese on the Braidwood Goldfields: historical and archaeological opportunities’, pp.35-58; Keir Reeves, ‘A songster, a sketcher and the Chinese on central Victoria’s Mount Alexander diggings: case studies in cultural complexity during the second half of the nineteenth century’, pp.175-192.

6. Shen Yuanfang, Dragonseed in the Antipodes , ( Melbourne : Melbourne University Press, 2001), pp.48-49.

7.Town and Country Journal , February 5 1870; J. E. Hodgkin in Australia , 1896 , Book 8, (place of publication unknown: Jonathon Edward Hodgkin, 1896).

9.Account books , Glendaurel , provided by Geoff Hassall.

10. Barry McGowan, Dust and Dreams: a Mining and Social History of southern New South Wales , 1850-1914, Ph.D., ( Canberra : Australian National University , 2001), pp.126, 133.

11. Franklin Hiram King, Farmers of Forty Centuries. Organic farming in China , Korea and Japan , ( New York : Dover Publications, 2004), p.115.

12. Mary Anne Bunn, The Lonely Pioneer, William Bunn, Diarist, 1830-1901 , (Braidwood: St Omer Pastoral Co, 2002), p.735.

13. Oral account by Rachel Burgess, October 2002.

14. On Craigie see T own and Country Journal , 18 February 1871; Sydney Morning Herald , 17 November 1860, 18 July 1871; Bombala & District Historical Society, Craigie Excursion on Saturday 31 October 1998, (Bombala: Bombala & District Historical Society, 1998); for Kiandra, information provided by Lindsay Smith.

15. Jack Bridle, ‘Memories and information of the Chinese’, Memories of Tumut Plains , residents and ex residents, (Tumut: Wilkie Watson, 1993), pp.12-14; Kerry Kell, ‘Agriculture at Tumut Plains’, Memories of Tumut Plains , pp.24-25; Malcolm Moy, ‘The Moy family’, Memories of Tumut Plains , p.64. Discussions with Bill Moy, 2000-2001.

16. Choi, Chinese Migration and Settlement, pp.30-31.

17. Martin Brennan, ‘Chinese Camps’, Votes and Proceedings New South Wales Legislative Assembly , (Sydney: 1883-1884), Vol.2; G. Buxton, The Riverina 1861-1891. An Australian Regional Study, (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1967), p. 224; Bill Gammage, Narrandera Shire , (Narrandera: Narrandera Shire Council, 1986), pp.141-144.

18. The Riverine Grazier , 4 May, 8 June 1881; The Dusts of Time, Lake Cargelligo and District 1873-1973 , (author and place of publication unknown, publisher unknown, 1973), p.54.

19. Hillston Spectator , 2 February 1895; The Riverine Grazier , 5, 8, 19 February, 5 April 1895.

20. Tom E Parr, Reminiscences of a NSW South West Settler , (New York: A Hearthstone Book, Carlton Press, Inc, 1977), pp.14-16; King, Farmers of Forty Centuries , p.79 ; Michelle Grattan, Back on the Wool Track , ( Sydney : Random House, 2004), pp.296-297.

21. Sydney Morning Herald , 30 December 1890; Barellan Progress Association and Improvement Society, Early Days in Barellan and District (Barellan: publisher unknown, 1975), pp.35-40.

22. The Riverine Grazier , 1 June, 13 August 1881, 18 January, 14 June 1882.

23. Sydney Morning Herald , 30 December 1890; Sherry Morris, ‘The Chinese Quarter in Wagga Wagga in the 1889s’, Newsletter of the Wagga Wagga and District Historical Society Inc, no. 276 (June-July 1992), pp.5-6.

24. Barry McGowan, ‘Reconsidering Race: The Chinese Experience on the Goldfields of Southern New South Wales, Australian Historical Studies , Vol.36, No.124, (October 2004), pp.312-332.

25. May, Topsawyers , pp.143-168; Lancashire , ‘European-Chinese Economic Interaction’, A Pre-Federation Rural Australian Setting, Rural Society , 10, No.2, (2000,) p.238.

26. Town and Country Journal , 19 May 1888.

27. Dolly Betts, Our Outback Home. Memories of Nymagee , (Dubbo: Nymagee CWA, 2003), p.30.

28. Leila Alderdyce, Gilgunnia. A Special Place , (Young: Leila Alderdyce, 1994), pp.24-25, 28-29.

29. King, Farmers of Forty Centuries, pp.1 73-175.

30. Information provided by Barbara Hickson; Western Herald , 13 April 1973; Bourke Banner , 1 March 1899; History of Bourke , Vol.X: p. 24.

31. Adelaide Observer , 17 May 1884.

32. G Svenson, Marginal People: The Archaeology and History of the Chinese at Milparinka , MA . (University of Sydney: G.Svenson, 1994), p.131.

33. NSW Department of Mines, Annual Report , ( Sydney : 1882), pp.98-99; 1883, pp.115-116.