by John Milfull

© all rights reserved

Colleagues and friends,

The filename of this picture essay is 3M.doc, in memory of my father-in-law Paul Romaneika, a German Russian of great charm and subversive intelligence who spent the last years of his migrant life as cleaner at Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing, St Marys, and who taught me the wonderful Russian expression ni auchin harascho, “not very OK”. It could easily have been expanded to 7M, to include the sub-title Milfull’s Medley of Marxist Metaphor, or even 10M, with a bow to the East German writer Heiner Müller, the real “subject” of the essay, and my consort, Her Majesty Helen Mary, who oversaw my own mole-like progress through heart failure and cataract surgery to re-surface blinking into the Sydney sunlight.

A remarkable photo by Joseph Gallus Rittenberg shows the East German writer Heiner Müller descending into a manhole within a Berlin subway station. The old cast-iron cover lies on a square of cobblestone among the new paving blocks of the renovated station; above right, an escalator points AUFWÄRTS [ up ], above left a stout and headless Berliner carries some shopping homeward.

The picture is redolent with metaphor – of Müller’s own approaching death and escape from the uneasy renovation of a consumerist Germany, and of his conflation of Marx’s image of the revolutionary mole and Benjamin’s “hapless angel”, now gone underground along with the deeply buried [lost?] wisdom of the masses, waiting for some improbable resurrection.

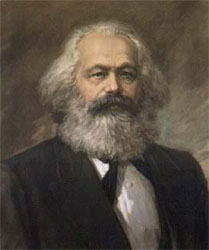

But the revolution is thoroughgoing. It is still travelling through purgatory. It does its work methodically. By December 2, 1851, it had completed half of its preparatory work; now it is completing the other half. It first completed the parliamentary power in order to be able to overthrow it. Now that it has achieved this, it completes the executive power, reduces it to its purest expression, isolates it, sets it up against itself as the sole target, in order to concentrate all its forces of destruction against it. And when it has accomplished this second half of its preliminary work, Europe will leap from its seat and exult: ‘Well burrowed, old mole!’

Karl Marx,The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

In the signs that bewilder the middle class, the aristocracy and the poor prophets of regression, we do recognise our brave friend, Robin Goodfellow, the old mole that can work in the earth so fast, that worthy pioneer – the Revolution. The English working men are the firstborn sons of modern industry. They will then, certainly, not be the last in aiding the social revolution produced by that industry, a revolution, which means the emancipation of their own class all over the world, which is as universal as capital-rule and wages-slavery. I know the heroic struggles the English working class have gone through since the middle of the last century – struggles less glorious, because they are shrouded in obscurity, and burked by the middleclass historian.

Speech at anniversary of the People’s Paper, 1856

Marx’s image of the revolutionary mole – borrowed from Shakespeare’s Hamlet via Hegel’s Philosophy of History1 – is inextricably linked with “waiting for history”, for a promised revolution that has failed to materialise, and later became particularly appealing to supporters of Luxemburg2 and Trotsky3 for whom the revolution remained unfulfilled. The idea of the revolutionary process continuing inexorably underground was suitably reassuring, but the metaphor has its “pitfalls”: although, as Bukharin4 pointed out, the mole has excellent hearing, it is virtually blind. In Marx’s own usage, there is a curious sense of the mole suddenly surfacing and defacing the neatly kept lawns of the Hampstead middle class. The metaphor, like the mole portrait above, is too cute by half. Its underlying naive optimism is not equal to the catastrophes of the twentieth century.

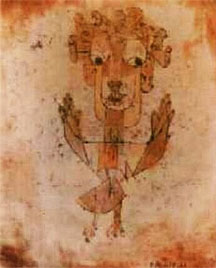

A Klee painting named “Angelus Novus” shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned towards the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.5

If Walter Benjamin’s image of the angel of history being blown backwards into an unforeseeable future was a grim enough rejection of nineteenth century “scientific” optimism, Heiner Müller developed it into an even more drastic critique, clearly marked by the full impact of the German catastrophe and imported Stalinism:

THE HAPLESS ANGEL Behind him mounts the silt of the past, raining detritus on wings and shoulders with the sound of buried drums, whilst before him the future piles up, pressing his eyes inward, exploding their balls like stars, gagging his speech, choking him with its breath. For a time one can still see the beating of his wings, within the booming still hear the rocks falling before above behind him, the louder the more violent his vain movement, sporadically as it grows slower. Then the moment closes over him, burying him rapidly where he alighted: the hapless angel is still, waiting for history in the petrification of flight glance breath. Until the renewed throbbing of mighty beating wings spreads through the rock and signals his coming flight.

Heiner Müller, 1958

History has stopped: its angel has not only “alighted”, come to a standstill, he has been buried under its ever mounting rubble heaps. Yet just as Benjamin’s image leaves the unknowable future open for the Messianic, which cannot be deduced from history but would represent its ultimate fulfilment, Müller’s text ends with the startling metaphor of the petrified angel breaking free from its bonds, a surprisingly heroic and “un-moleish” image. By 1977, this messianic vein seems blocked for the foreseeable future. In a letter to Reiner Steinweg, which is also a commentary on the revolutionary dreams of the student left in West Germany, he writes:

History has adjourned the case to the street, and the worker’s choruses of Brecht’s The Measures Taken are now silent; humanism appears only in the guise of terrorism, the Molotov cocktail is the zenith of bourgeois education. What remains: isolated texts, waiting for history. And the leaky memory, the fragile wisdom of the masses, the instant threat of forgetting. In a terrain in which the teaching is buried so deep and which is strewn with landmines as well, one must occasionally stick one’s head in the sand (mud rock) to see the way ahead. The Moles, or constructive defeatism.

Heiner Müller, 4.1977

Castle and Hotel, Neuhardenberg (formerly Marxwalde)

Rittenberg’s photo is published in the prospectus for the “prestigious cultural program” of the Stiftung Schloss Neuhardenberg GmbH [Neuhardenberg Castle Foundation Ltd.] The castle formerly belonged to the family of the Prussian reform chancellor Hardenberg; its owner since 1921, Carl Hans Graf Hardenberg, was expropriated and sent to Sachsenhausen by the Nazis for his part in the Stauffenberg conspiracy. In 1949, the GDR government confirmed the expropriation and renamed the town Marxwalde [ Marxwood ]; it was developed as a model village with a government airbase.

In 1996, the property was returned to the Family Hardenberg. It was bought in 1997 by the Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband [Union of German Savings and Giro Banks] and renovated at great expense, with the addition of a five star hotel. The “prestigious cultural program” includes an exhibition on Müller and the avant-garde artist Joseph Beuys, now both safely dead, as “Partisans of Utopia”. Transport to Neuhardenberg is difficult, guests are advised to take a 20km taxi ride from the nearest railway station, and there is an active campaign to reopen the GDR airfield for tourists and VIPs. The state rail connecting bus that runs on weekends and holidays in summer is not permitted to stop in front of the complex, but drops passengers off at a discreet distance about 500 metres down the road. I was beset with mirages of moles popping up through the manicured lawns to be stun-gunned and carried away in sacks.

The Metro in St Petersburg [in molespeak, Leningrad ] is the deepest in the world – 300 metres – due to the swampy ground on which the city is built. It is now completely inadequate to serve the needs of a city of five million, and rush hour at an exchange like Mayakovskaya Station rivals familiar images of the Tokyo subway. Particularly threatening are the doors to the Green Line trains, which open only when the train has drawn level – you push and shove your way into an invisible train, hoping it’s going in the correct Cyrillic direction.

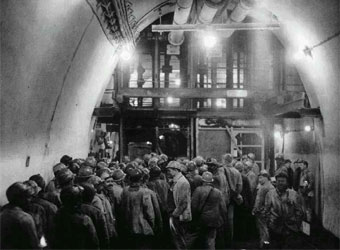

St Petersburg, we are told, is plagued by a host of defective manhole covers,6 inviting involuntary descent to the underground – a fitting image of post-Soviet times. I shall always remember the group of young soldiers maimed in the Chechen war and begging/busking in a connecting tunnel, or, for that matter, the group of young recruits in a Metro carriage struggling against an overwhelming desire to make up for lost sleep and return to the cocoon of childhood. It may be a long time before the dead souls of the underclass awaken. As elsewhere, the new ruling class does not use the Metro; their shiny Mercedes and BMWs push through an endless chaos of elderly Volgas and Ladas, wildcat private taxis, trolley buses, trams and mini-buses. President Putin is building a new presidential palace half way between the city and Peterhof, the glorious estate of Peter the Great. For those that use the Metro, life is tough, tougher and more unjust than in Soviet days. If there is a third revolution, it will begin in the metro, like the workers bursting out of their underground city in Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis, not in the study of some elegant eighteenth century mansion.

Lenin’s Study, Kshesinskaya Mansion

For all its confusion and woolliness, Metropolis contains a remarkable synthesis of images/metaphors which probably have more to do with its enduring impact than the “reconciliation between capital and labour” that so appealed to Hitler and Goebbels, and was so brilliantly caricatured by George Grosz:

Head shakes hands with Hands |

George Grosz, Einheitsfront |

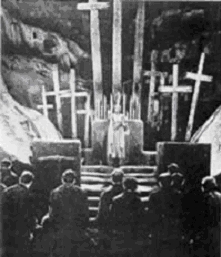

The old religious imagery of Heaven and Hell is fused with a vertical metaphor for modern industrial capitalism; the workers dwell in the depths below, even below their hellish man-eating machines, hidden from sight of the ruling class and the delights of the jeunesse dorée . The image of miners descending into the bowels of earth to dig out the food for the Moloch of early capitalism was clearly inscribed in Lang’s imagination; his underground is mine, maw of hell, the potential source of chaos and revolution, but also, as catacomb, of the Messianic. Thatcher knew what she was doing in crushing the British miners.

|

mineshaft at Smallbij |

|

|

The Messiah is coming! |

where he led |

The [provisional] End of History diagnosed by Müller in 1958 was of a very different kind to Francis Fukuyama’s post-Hegelian declaration that the world spirit had finally realised itself with the Fall of the Soviet Empire and the triumph of Anglo-Capitalism – perhaps we should add the New Prussia to the New Rome as a metaphor for Dubya’s incoherent empire? I’m sure he has a fantasy about seven league boots!

For Müller, the End of History was its paralysis, the petrification of the “movement which transcends existing conditions” and its burial with the “wisdom of the masses”. There followed the thirty years which could well be termed, on both sides of the curtain, the period of stagnation, and then suddenly, in the mid-eighties, the false tremor of perestroika and the collapse of the House that Joe Built.

Like so many of us at the time, Müller allowed himself to be briefly seduced by the Gorbachev dream of a socialist democracy, but paid the penalty with an extended post-unification hangover, real and metaphorical. For him it now meant a different kind of end, the suppression of all the dreams and sufferings of the past in the name of a superficially bland present. He would have enjoyed Rodney Smith’s acute dissection of Tony Blair’s “New” Labour as a “rejection of history”7 and seen it reflected in the mantras of the “New Europe”. But if nothing seems to be happening – apart from the occasional terrorist attack, natural or man-made catastrophe – there is a new nervousness, a sense of walking on eggshells that separates us from the underground and the “underclass”, a neologism with theological resonance, the new “damned of the earth”.

Be that as it may, Fukuyama’s claim is nowadays no more than a bad joke; if this is triumph, it feels distinctly fraught, and there is quite simply too much [shit] happening to talk of any ends but apocalyptic ones. Müller, on the other hand, came to see this end of history in another and far more menacing light. While he would no doubt have taken grim pleasure in the iconography of September 11 th, a kind of neo-Metropolis attacked by its own technology, the horrific images of the Aum attack on the Tokyo subway system in 1995 probably better reflected his growing conviction of a perpetual “state of emergency” waiting to erupt from the underground of repressed fear and suffering:

|

from above … |

Heiner Müller in conversation with Hendrik Werner

(Berlin, 7 May 1995):

[HM]:.. what Lessing [as an apostle of the Enlightenment] repressed in his refusal to dream was later to explode in Kleist’s work … For a time one can forbid oneself to dream out of self-discipline or fear, but eventually [the repressed] erupts horrifically, and the dream becomes a rotating reality.

[HW] In “The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” Marx sacrifices the rememberings of world history to historical materialism’s axiom of progress, the dead to the telos of a secularised history of redemption. In a political-economic system like ours, which rejects temporality and memory in favour of the ahistoricity of computer storage, how can it still be possible to exhume the dead and to remove the “burden of dead generations” from the shoulders and minds of the living when apparently no one suffers from it any longer?

[HM] Suffering is the crucial term. I’m sure you know Baudelaire’s line: “boredom is pain spread out over time”. Here pain is experienced as boredom. Since that is the way of managing pain that is most likely to lead to sudden and unforecastable eruptions of violence. Running amok arises from boredom. And that panic is everywhere – when one turns a corner, a homicidal maniac may be waiting. It all stems from that repressed pain and fear which people are now trying to mobilise and manipulate. http://www.hydra.umn.edu/mueller/hendrik.html

A prophetic anticipation of the politics of fear as practiced by our leaders! But the “pain that is spread out over time” has a different source. In theTheses on the Philosophy of History, Benjamin savages social democratic writers for their astonishment that Fascist barbarism can still be possible in the twentieth century. Waiting for the inevitable outcome of history supposedly guaranteed by Marx’s dialectic, they betray not only the oppressed of the present, but the claim of preceding generations:

Like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak Messianic power, a power to which the past has a claim. That claim cannot be settled cheaply … Every image of the past that is not recognised by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.

Ignoring this claim and banning the images of past hope and suffering leads to the “boredom’, the uneasy, constantly imperilled stasis that has replaced any dream of a better future.

How was it possible that Fukuyama’s “master narrative” of the end of history and the triumph of liberal democracy could suddenly be interrupted by claims that the “world had changed for ever” on 9/11, and that the historical mission of liberal democracy must now take the form of a new crusade? These two superficially contradictory discourses (Fukuyama and Huntington, if you like) are however quite happy coexisting with one another. The supreme irony is perfectly exemplified in a recent speech by George W. Bush, who attacked the Shia leadership in Iraq for trying to achieve their democratic rights through violence: what other public justification has the “coalition of the willing” left for its presence in Iraq than the imposition of democracy through violence? But of course, it depends on whose violence it is.

But the contradiction is only superficial. Both positions are based on a radical “dehistoricisation” of history in the name of possibly the glibbest concept of “progress” yet known to humanity, and the eruptions of violence are directly linked to the repression of the “claims of the dead” and, for that matter, of most of the living targets of such secularised and technologised messianism. The present is only the latest stage of a continuing emergency, which could only ever be resolved if these claims were at least partly recognised and the uncanny boredom of the “end of history” were reinvested with the genuine suffering on which it is built.

But perhaps history too has “gone down a manhole”, such as this curiously menacing example from St Leninsburg, where red marks the spot:

MORE SAY FOR THE DEAD!!

The concept of the nation is not innocent; it is an ideological, bloodthirsty construct. The nation is a community of victims and is built on victims, especially the Geman nation, it needs victims, as is evident up to 45 and in its underground extensions. We must free ourselves of this cycle of victimisation.

The dead have a continuing impact through their ambivalence: they are honoured with flowers and wreaths, yet hindered by concrete slabs from rising from their graves. [Klaus] Heinrich said he had once clapped spontaneously on seeing a banner demanding “More Say [co-determination] for the Dead”. Heiner Müller, in whom he saw a child-like naiveté rather than [the] cynicism [of which he was often accused], was the great dramatist of the repressed unconscious.

Report of a speech by Klaus Heinrich at the symposium “Burying the Nation”,

Berlin 9.November 2002, on Heiner Müller, Germany and the War,

http://www.taz.de/pt/2002/11/11/a0154.nf/text

Self-Criticism

My editors rummage through early texts

It gives me cold shivers to read them,

Texts that I wrote POSSESSING THE TRUTH

Sixty years before my due date to die

On the TV screen I can see my countrymen

Voting with hands and feet against the truth

I thought I possessed forty years ago

What grave can protect me from my youth

Heiner Müller

And a final Message from Milfull, fit for my own epitaph?

KEEP BURROWING, FELLOW MOLES!

THE DIRECTION REMAINS UNCLEAR –

BUT WE MAY AT LEAST SUCCEED

IN UNDERMINING THE WHOLE

CRAZY SUPERSTRUCTURE

OF

NEO-CONSERVATIVE CANT!

John Milfull is a Professor in European Studies, University of New South Wales

FOOTNOTES

1. Spirit often seems to have forgotten and lost itself, but inwardly opposed to itself, it is inwardly working ever forward (as when Hamlet says of the ghost of his father, “Well said, old mole! canst work i’ the ground so fast?” [Act I, Scene V]) until grown strong in itself it bursts asunder the crust of earth which divided it from the sun, its Notion, so that the earth crumbles away. At such a time, when the encircling crust, like a soulless decaying tenement, crumbles away, and spirit displays itself arrayed in new youth, the seven league boots are at length adopted.

Hegel’s Lectures on the History of Philosophy,

Section Three: Recent German Philosophy

E. Final Result

http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/hp/hpfinal.htm

2. See Rosa Luxemburg, “The Old Mole”, http://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1917/05/oldmole.htm

3. cf. Leon Trotsky On Britain, http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/works/britain/britain/ch09.htm:

“Despite all obstacles from the Communist International, the mole of the British revolution burrows much too well its earthy path.”

4. “And everything in nature seems informed with a plan: the mole, living under the surface of the ground, has little blind eyes, but very excellent hearing.”

http://www.marxists.org/archive/bukharin/works/1921/histmat/1.htm

5. Walter Benjamin, from Theses on the Philosophy of History [ On the Concept of History ] (1940), Illuminations, London 1973, p. 259-60

6. see http://www.enlight.ru/camera/traps/index.html for some fine examples!

7. Rodney Smith, “The Sources of New Labour”, in Britain in Europe. Prospects for change, ed. John Milfull, Aldershot 1999, 113-134.