by John Milfull

© all rights reserved

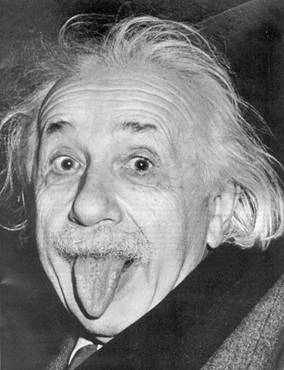

If I have a favourite photograph, it is Albert Einstein sticking out his tongue at the camera and the world in general. It is the kind of cheeky disrespect for convention that I associate with creative intelligence, never content to accept received opinion without questioning, impatient with the “order of things” and seeking for radical solutions to its intractable problems. It could serve as an illustration in an anthology containing Brecht’s great poem In Praise of Doubt and Benjamin’s The Destructive Character, which place this questioning firmly in the service of the future, as the negation of the unacceptable to clear a path ahead. But above all it seems to me a constant recourse to the “inner child”, the child that can see the adult world with a clarity that penetrates its absurd rituals and unfounded assumptions. It is a view from below, “uncorrected” by any hindsight. I could never muster up much enthusiasm for Goethe’s metaphor of the creative life, a “repeated puberty” – his must have been more fun than mine – but the capacity to reinvent oneself it implies seems to have more to do with preserving this “inner child” on our journey through adulthood.

|

|

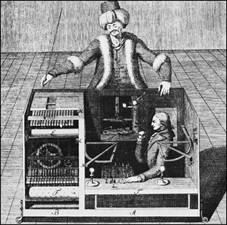

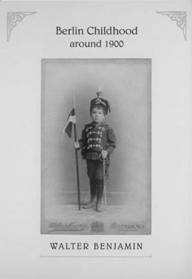

This “child’s eye view” is shared with the little people, the dwarves and gnomes of fairy tale and real life. In many ways, the fairy tale dwarf is the projection of its “strangeness”, so alien to the normalities of adult life, a kind of inbuilt Verfremdungseffekt which the real dwarfs, whose “short stories” ABC television recently documented so sensitively, have to carry through everyday life. In Walter Benjamin’s Berlin Childhood around 1900, the little hunchback, das bucklicht Männlein of German folklore, a cousin of Rumpelstiltzchen, is at first a bogey, but becomes the organising principle of his childhood memories, the little one who was there and saw all its moments. Later, he finds this quality in Kafka’s Aufmerksamkeit, his attentiveness to all of creation, the “natural prayer of the soul”.1 And finally, in the dark days of 1940, the dwarf theology, hidden within the chess-playing machine of history, is the source of hope for the future that lies behind the spread wings of angelus novus.2

It is hard to imagine a “child-like” Adorno; an early photo with his “only real [doggy] friend”, seems more a competition at looking solemn. In later life, his relentless quest for intellectual sophistication transformed any nostalgia he may have felt into an occasional twinge of yearning for the pre-capitalist world. He could not abide “infantility” in others, he was the genuine grown up, only more so, as it says in the Jewish joke. While deeply indebted to Benjamin in many ways, he was clearly put out by the flashes of unorthodox, child-like brilliance, the attentiveness to apparently trivial details which are the real strength of his critical method. He tried hard to “correct” Benjamin’s errors, with all the earnestness of a younger brother trying to restrain an eccentric elder. Above all, like Benjamin’s friend Gershom Scholem, the distinguished scholar of Kabbalah and Zionist, he never really forgave him for his flirtation with the playwright Bert Brecht, who practised a very different brand of Marxism, and in language accessible to the common herd. In the 1962 essay Commitment he got his own back on the rascal who had led naïve Walter astray:

.the process of aesthetic reduction he undertakes for the sake of political truth works against political truth. That truth requires countless mediations, which Brecht disdains. What has artistic legitimacy as an alienating infantilism – Brecht’s first plays kept company with Dada – becomes infantility when it claims theoretical and social validity.3

The peculiar reference to “Dada” and Brecht’s “first plays” masks the unexpected depth and enthusiasm of his 1930 review of Mahagonny,4 which contains not only an acute analysis of the opera but a splendid account of the strengths of the child’s eye view:

But what the direct gaze cannot discern there may reveal itself to the oblique glance of the child, to whom the trousers of the adult it looks up to appear as mountains, with the face as a distant summit. This skewed infantile way of looking at things, feeding on stories of Indians and pirates, becomes a means of demystifying the capitalist order – its factory sites transform themselves into prairies in Colorado, its crises into hurricanes and its power apparatus into revolvers at the ready. In Mahagonny the Wild West is revealed as the immanent fairy-tale in capitalism, just as children assume it in their game-playing. The projection through the medium of the child-like eye transforms reality until its basis can be recognised, but does not dispel it into mere metaphor, but grasps it simultaneously in its direct historical concretion.

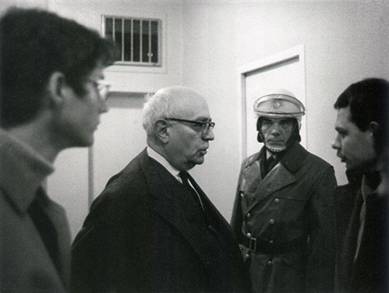

After the war, Adorno’s assaults on the “Stalinist” Brecht – one wonders if he ever read his conversations with Benjamin in Denmark, and Brecht’s “Stalin poem”, in which the great leader appears as an ox – were partially motivated by his desire and need to fit into the West German scene. The images of him setting the police on activist students, or fleeing from topless female graduates are not endearing.

Yet there can be little doubt that it was precisely Brecht’s gift for a “theatrics of utter simplicity” (as Adorno terms it) on stage and in conversation which struck a sympathetic chord with Benjamin, in contrast to the hyperintellectual ruminations in the “Grand Hotel Abgrund” [ luxury hotel on the edge of the abyss, Lukàcs on Adorno5]. Adorno never forgave him this desertion to infantility.

Oddly enough, the definitive implementation of the child’s eye view had just taken place, in Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum (1960). In a flash of genius, he combines child and dwarf in the figure of Oskar Matzerath, who decides not to grow any more at the ripe old age of three, preserving his child self under the carapace of the dwarf. His dwarfish view is as politically incorrect, as skewed and unsentimental as in Adorno’s prescription, able to penetrate the false veneer of everyday life in the Third Reich.

In 1958, Wolf-Dietrich Schnurre had used the image quite differently in a little parable called The Dwarfs.6 “Their crime?” he writes, “they were too small”. It is a charge the dwarfs cannot refute: they are condemned and led to be burnt at the stake.

.. it is hard for them to believe that you have to be bigger to live undisturbed; they thought that their very inconspicuousness was their guarantee of remaining unnoticed for ever. Now the opposite has occurred… They wear long black coats, greased-down locks peep out from beneath their high hats decked with lilac ribbons. Now the bailiff drags them up the steps of the town hall and reads out the charges again: too small, too delicate, too nimble. But even here, no one listens. It doesn’t worry the bailiff, he’s only doing his duty.

The rest of the text makes it even clearer that Schnurre has chosen the dwarfs to represent those judged “unworthy of life”, the dwarfs, the disabled, Jews, homosexuals and others who fell victim to the Nazi hysteria of racial hygiene, while transplanting the events into a feudal Germany given to burning witches and all who threatened its uneasy instability.7

Unlike Max Frisch, whose influential parable The Jew from Andorra is based on the premise that Jews are the same as everyone else, they are simply forced to adopt a stereotype imposed on them by anti-Semites,8 Schnurre chooses an old and traditional image of visible difference for his scapegoats. If, at the end, we find out that the Jew from Andorra is not really a Jew at all, Schnurre’s dwarfs have no such way out, even after death; they wear their difference, their only possible refuge is to avoid being noticed. If Frisch’s strategy errs in eliminating or ignoring genuine difference, Schnurre presents it as fate, as the sign of the victim. Affecting as the text is, one has a peculiar feeling that the dwarfs have just caught it again, been chosen by well-meaning non-dwarfs to wear the symbolic mark of the martyr.

Oskar Matzerath, the anti-hero of Grass’s Tin Drum, is a dwarf of a very different kind, a dwarf by choice and in protest. Indeed, if we are to believe his mentor Bebra, the theatre dwarf, descendant of Prince Eugene of Savoy and later Captain of the Propaganda Company and impresario, he is not alone in this: 9

He was in braces and slippers, carrying a pail of water. Our eyes met as he was passing and there was instant recognition. He set down his pail, leaned his great head to one side, and came towards us. I guessed that he must be about four inches taller than I.

‘Will you take a look at that!’ There was a note of envy in his rasping voice. ‘Nowadays it’s the three-year-olds that decide to stop growing… On my tenth birthday I made myself stop growing. Better late than never.’

Bebra, you will remember, is so impressed by Oskar’s glass-shattering skills that he wants to “hire him on the spot”:

Even today, I am occasionally sorry that I declined. I talked myself out of it, saying: ‘You know, Mr Bebra, I prefer to regard myself as a member of the audience. I cultivate my little art in secret, far from all applause…”. Mr Bebra raised a wrinkled forefinger and admonished me: ‘My dear Oskar, believe an experienced colleague. Our kind has no place in the audience. We must perform, we must run the show. If we don’t, it’s the others that run us. And they don’t do it with kid gloves.’

His eyes became as old as the hills and he almost crawled into my ear. ‘They are coming,’ he whispered. ‘They will take over the meadows where we pitch our tents. They will organise torchlight parades. They will build rostrums and fill them, and down from the rostrums they will preach our destruction. Take care, young man. Always take care to be sitting on the rostrum and never to be standing in front of it.’

Hearing my name called, Mr Bebra took up his pail. ‘They are looking for you, my friend. We shall meet again. We are too little to lose each other. Bebra always says: Little people like us can always find a place even on the most crowded rostrum. And if not on it, then under it, but never out in front.’

Meet again they do, during the war, when Oskar belatedly joins the troupe to perform in France and breakfast on the concrete of the Atlantic Wall before the invasion. And finds his true other half, the gentle Roswitha Raguna, in the air-raid shelters of Berlin, only to lose her thoughtlessly to a shell from a naval gun in Normandy. But Bebra, true to his own prescriptions, survives the war and reappears to impose a penance on Oskar for his thoughtlessness – to help himself and others to remember.

Reality is far more horrific than fiction, even Grass’s fiction. In the middle of the dismal controversy in the German press that surrounded Grass’s election to the Nobel Prize, the Spiegel ran a story about a troupe of real theatre dwarfs from Romania. The seven Ovitz siblings survived the turmoil of the Nazi Empire with faked passports and a cleverness worthy of Bebra himself, but were finally overtaken by the Final Solution in Hungary, May 1944. After some farewell performances for a group of German and Hungarian officers in their birthplace, Sighet, they mounted the cattle-wagons to Auschwitz, only to find that they were to enjoy the individual attention of Dr Josef Mengele, their torturer and, by a savage twist of irony, their protector.10 They emerged from his mad experiments scarred for ever, but still alive.

I like to think that the ghost of Master Bebra was involved in their reemergence. While German critics wondered whether Grass could ever be forgiven for unacceptable views on German unification, the Holocaust and other outdated matters, and for failing to write according to their prescriptions, international colleagues from Rushdie to Vonnegut showered him with tributes. The wittiest was from the Austrian writer, Karl-Markus Gauss: “As they couldn’t very well give the prize to Reich-Ranicki [Grass’s nemesis, the so-called “Pope of West German literature”] straight off, it’s quite OK.”11 But the finest tribute was the picture of Perla Ovitz two issues later, a reincarnation of Oskar’s Roswitha, gentle and indestructible, bearing unconscious witness to the power and strength of Grass’s imagination.

It may well be that an encounter with real theatre dwarfs was lodged in the recesses of Grass’s memory,12 but the invention of Oskar remains one of those literary inspirations at the starting point of so many great novels. It is not hard to discern his parentage. On the one hand, he belongs to the family of the strolling players, the saltimbanques and the circus people so central to the iconography of impressionism and symbolism, images of the artist-outsider banned to the margins of bourgeois society and destined to see from without its phony apocalypses and paradises. On the other, he seems a direct incarnation of Adorno’s comments about the “perspective of the child-like eye” which might distort reality back into recognition – the ability to see “from below”, without the unconscious censorship of growing up and all the projections onto the world around us it brings with it, so that we end up seeing only what we’re meant to see.

But Grass’s invention of the “dwarf’s eye view” gained a particular and path-breaking significance. Not only does Oskar see, in quite specific ways, what adults no longer see – the view from under the skirt, the table, the rostrum, which he continues to enjoy right through his teenage, as privileged and often malevolent mascot who can go anywhere – his view from below of Danzig, the Third Reich, of Germans, Jews, Poles and Dwarfs addressed a problem of a different magnitude, the justificatory, self-censoring approach to the Nazi past which had characterised most earlier attempts to deal with it on both sides of the border between the two German states. In a story published in 1975, A Pistol at Sixteen, Erich Loest wrote of the difficulties of confronting his own, unheroic past in the Hitler Youth – the approved models for GDR novels on the Nazi past demanded a heroism, resistance and solidarity which he had never encountered.13 In the West, the models were less coercive, but no less dominated by the compulsion to neatly excise the author from any group pictures of Hitler’s extended family. It took many years before the narration, and the historiography, of everyday life in the Third Reich could break though this urge to justify and revise, to emerge on the side of the angels.

Oskar is no angel, and his clear vision uncovers many uncomfortable truths. The ultimate paradox of German Fascism is the co-existence of a bourgeois normality, fed and strengthened explicitly by the regime, with the horrors of total war, genocide and the internal brutalisation of society. This normality – and its axiom, “we knew nothing about all that” – is cut through by the piercing, uncensored gaze of the dwarf, who sees the brutalities of everyday life, the all too human links joining Jews, Poles and Germans and their entrapment in the mad rhetoric of national greatness. I am not at all sure that his verdict on our greedy and desensitised societies would be any more positive. They, too, can only be seen and understood from below.

John Milfull is Visiting Professor in European Studies, University of New South Wales

FOOTNOTES

1. Texts and references at http://bucklichtmaennlein.blogspot.com/

2. See Irving Wohlfarth’s magisterial essay ‘On Some Jewish Motifs in Benjamin’, in A. Benjamin (ed.) The Problems of Modernity: Adorno and Benjamin, pp. 157-215. London: Routledge 1989

3. From Adorno, Theodor W. “Commitment” (1962). in: Notes to Literature, Volume II; edited by Rolf Tiedemann; translated from the German by Shierry Weber Nicholsen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992) (pp. 76-94), excerpt, pp. 82-87 at http://www.autodidactproject.org/quote/adorno18-brecht5.html

4. Reprinted in Moments Musicaux, Frankfurt 1964, 131ff.

5. http://www.marcuse.org/herbert/people/adorno/Adorno100GtagSpiegel038.htm

6. Wolfdietrich Schnurre, “Die Zwerge”, reprinted in Lesebuch. Deutsche Literatur zwischen 1945 und 1959, ed. Wagenbach, Berlin 1980, pp. 182-3. Translation by J.M.

7. cf Peter O. Arnds, Representation, Subversion, and Eugenics in Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum, Boydell & Brewer 2004

8. Max Frisch, “The Jew from Andorra”, translated in Postwar German Culture, ed. C.E. McClelland and S.P. Scher, N.Y. 1974, pp. 235 ff. Frisch was clearly influenced by Sartre’s thesis in Anti-Semite and Jew, N.Y. 1948, that the Anti-Semite “creates” the Jew. I would have hoped that Jews had something to do with it as well.

9. Günter Grass, The Tin Drum, tr. R. Mannheim, London 1989, p. 109-10

10. “Komm zu Mengele”, Der Spiegel 42 / 1999, pp. 212 ff.

11. Später Adel für das Wappentier, “Ich bedaure nichts”, Der Spiegel 40 / 1999, pp. 294 ff. See also “Von Shakespeare bis zu mir”, Der Spiegel 41 / 1999, pp. 332 ff.

12. Since I wrote the first version of this paper, Grass has revealed, in Peeling the Onion, how, “on his way to join the Waffen-SS, he saw a group of dwarfs performing in the bomb shelter of a Berlin railway station.” (Timothy Garton Ash, ” The Road from Danzig”, NYRB 54, August 16 2007, note 2; c f. Günter Grass, Beim Häuten der Zwiebel, Göttingen: Steidel 2006, 124-126 ). This is almost too good to be true.

13. Erich Loest, “Pistole mit 16”, in Etappe Rom, Berlin 2 1978, pp. 73-120; see esp. pp. 89-91.