by Margaret Jolly

© all rights reserved

AHR is now published in PDF and Print-on-Demand format by ANU E Press

A Reading of Southern Theory

In her recent book Southern Theory Raewyn Connell has challenged the domination of social theory by those in the metropoles of Europe and North America. She argues that this has entailed a view of the world from the skewed, minority perspective of the educated and the affluent, whose views are then perpetuated globally in educational curricula. The South appears in such global theories primarily as a source of data for Northern theorists rather than as sites of knowing and self-conscious social reflection, places where important social theories are also developed. Through a survey of nineteenth and twentieth-century ‘Southern theory’ from Latin America, Iran, Africa, India and Indigenous Australia, Connell aspires to restore the fullness of the world to social science, to include its many voices in a more democratic global conversation.

The volume offers a multifaceted argument. It narrates an alternative ‘origin story’ for sociology and, by implication, anthropology. It highlights the global reach of early theorists like Comte, Spencer and Durkheim in their obsessions with the process of modernity, linking European ancients and contemporaneous ‘primitives’ in narratives of progress, debating the origins of human differences of race, gender and sexuality: ‘Sociology displaced imperial power over the colonised into an abstract space of difference’ (Connell 16), a claim equally true of early anthropology (see Fabian). Connell suggests that the more restricted focus on industrialised metropolitan societies was linked to the professional growth of sociology in the United States, from the urban ethnography of the Chicago School to the abstract social theory of Talcott Parsons. Such modern ‘general’ theory, from Parsons through Coleman, Giddens and Bourdieu aspires to universals, irrespective of time and place. Yet all such theories, albeit in different ways, fail to acknowledge the specificity of their ground of knowing, they ‘read from the centre’, with sweeping gestures of exclusion and grand erasures. ‘Whenever we see the words “building block” in a treatise of social theory, we should be asking who used to occupy the land’ (Connell 47).

Although some social theorists like Giddens and Hardt and Negri strenuously detach contemporary modernity from the colonial past, Connell discerns continuity and a perduring imperial gaze in much Northern theory. Theories of globalisation, translated from economics into sociology in the 1990s, too often witnessed the global spread of modernity through theoretical reifications of ‘culture’. In Chapter 3 Connell consummately critiques the agonising antinomies of such literature—global and local, homogeneity and difference, dispersal and concentration—as vortices in swirling debates. Claims about abstract linkages conceal the parochial power of the metropolis while breathless declamations about tsunamis of global transformation become performative utterances constituting the very facts being researched. Again the ‘South’ is a source of data but not of ideas.

The latter parts of the volume rather look to the South as site, or rather sites, of social theory, extending from Australia, through Africa, Latin America, Iran and India. From the early use of Spencer and Gillen’s ethnography of Indigenous Australians in Durkheim’s theory of elementary religion to the twentieth-century canon of Australian sociology (including Encel, Bottomley, Braithwaite, Bulbeck, Pusey, Pauline Johnson, and Connell herself), Connell shows how Australia, a rich if peripheral nation, has fed, and sometimes stretched, metropolitan debates in social theory. She affords a tantalising glimpse of how Indigenous Australian social theory, as evinced in visual art practice, can illuminate modernity, as in Vivien Johnson’s creative analysis of the rock band, Radio Birdman.

A similar potential emerges in discussions of Indigenous knowledge in Africa, as in the claim by Akiwowo that Yorubra oral poetry was a fertile source for African social theory, an exemplar of ‘Indigenous sociology’ (and closely akin to many anthropologies, foreign and Indigenous which have long suggested alternative theories of the social and the person in non-metropolitan places, e.g. Geertz, Strathern). In several ensuing critiques of Akiwowo, the problems of reifying an unchanging culture, uncontaminated by colonial processes, and homogenising elite male practice as ‘tradition’ were highlighted (cf. Jolly “ Politics of Difference” and “Specters of Inauthenticity”). As Connell astutely observes, a radical epistemology for international sociology betrayed a conservative older male view of social change in Africa (96). Claims for a distinctive African philosophy, like thenégritude movement in art and literature were potent rejections of imperial presumption and power. But, as the Dahomey philosopher Houtondji suggested (105-6), they threatened to confine Africans yet again in the essentialisms of race and the authenticities of culture. Connell suggests that similar perils prevail in the more recent rhetoric of an ‘African Renaissance’, even if the distinctive location of Africa-focused intellectuals needs to be acknowledged.

The interpenetration of indigenous and exogenous knowledge is perhaps even more deeply sedimented in the ground of Latin America. In Chapter 7, Connell focuses on the question of autonomy from metropolitan power in the work of theorists such as Raúl Prebisch, Cardoso and Faletto, Hopenhayn, Montecino and Canclini. They perforce focus attention on the place of imperial centres, and especially the United States, as much as on the specificities of Latin American experiences of dependency and development. The historical context of such theories moves from the Cold War period with US military support of client dictators, to the more veiled imperial power of neoliberalism initiated in Chile under Pinochet. All these theorists selectively deploy and critique generations of Northern theorists, from Kroeber to Bourdieu, from Frank, Amin and Wallerstein to Lyotard and Baudrillard. But they regularly refuse to be captive to the false claims of universality and the totalising metanarratives of the North, as they address the diverse specificities of Latin American life and the regional potential for progressive politics.

The chapters on Iran and India (6 and 8) raise fascinating visions of alternative universals. Islam is focal in Connell’s empathetic reading of the texts of al-Afgahni, Al-e Ahmad and Ali Shariati in translation. Al-Afghani wrote in the 1880s, the latter in the 1960s and 1970s, but all were preoccupied with the strength of Islam in the face of Western domination. Al-Afghani refuted Western materialism but celebrated Islam as the most rational of religions and, like modernist science, open to proof and refutation. In his view, if ulama were to offer true leadership, Islam would be a force for resistance and British imperial power might be defeated. Later social theorists continued this critique, Al-e Ahmad in his famous, if unruly and misogynist, attack on ‘Westoxication’, raged against the alienated and impotent Westernised male and the vapid materialism of secular nationalists. Islam and the ulama were again seen as the key to resistance and regeneration. His successor, Ali Shariati, drew on Marxist class analysis but critiqued its materialism, celebrating Islam rather as a ‘this-wordly’ religion which potently challenges unjust domination. He avowed the unity of God and the unity and equality of humankind, including women. His ideas in part incited the Iranian revolution but the conservative forces around Khomeini triumphed in 1981, culminating in a more militant and fundamentalist resistance to the ‘West’.

The struggle with British imperial power and knowledge in the subcontinent has generated similarly powerful anticolonial critiques, from the revolutionary thought and political practice of Gandhi, through the later scholarship of the subaltern theorists, led by Ranajit Guha from 1982. Connell offers a telegraphic distillation of their influential approach and the ‘extraordinary outpouring’ of criticism it provoked, including the alleged neglect of caste and of women in earlier theorisations of the ‘subaltern’. Connell alludes to the complex relations between Western and Indian feminisms and the unfortunate reproduction of radical feminist universalisms about ‘patriarchy’ and ‘nature’ in the ecological feminism of Shiva. She finds more congenial southern theorists in the work of anthropologist Veena Das and her collaborator, psychologist Asis Nandy. Das practises anthropology ‘not by immersion in a warm bath of traditions, but by the painful route of studying … “major conflicts”’ (178), for example the violence against women during Partition in 1947 and the horror of the Bhopal chemical disaster in 1984. In such conflicts Das depicts communities not as primordial entities but as emergent political constructs and deconstructs the ‘truth’-making of states and courts, to affirm the truth incarnate in the victims of violence and injustice.

Nandy (who collaborated with Das in research on Partition violence), explores what colonial violence did to bothIndians and the British, for instance in the complicity between exaggerated imperial masculinity and Indian ‘warriorhood’ (cf. Jolly, “ Moving Masculinities”). Through studies of writers like Kipling, Aurobindo and Gandhi, Nandy charted the psychological damage, the shared ‘inner pain’ of colonialism, which potentially offered a recognition of shared humanity, as for Gandhi. Although Nandy is much indebted to metropolitan psychology and psychoanalysis, Connell rightly discerns the influence of rich and diverse Indian ideas in Nandy’s illuminating explorations of the personal, refracted through the public, political texts of books and films.

Through this brief review I hope I have suggested the range of Connell’s reading beyond the confines of metropolitan social theory. But what is it that connects these several sites, what articulates these articulate congregations of Southern theorists? In the Introduction, Connell stresses that her conception of the South is relational. Her purpose is ‘not so much to name a social category as to highlight relations of power’ and especially ‘periphery-centre relations in the realm of knowledge’ (viii). Those in the South are authors of theory and not just objects of study, and the ground of their knowing, their location, matters. In the conclusion Connell acknowledges the problems inherent in the labile languages of global divisions: North/South, West/East, First World and Third World, developed/underdeveloped, centre/periphery (212; cf. Slater). Connell prefers the first and last couplets and challenges those, like Hardt and Negri, who argue that all such demarcations are obsolete in this era of globalisation. Naming such divisions is for her ‘an absolute requirement for social science to work on a world scale’ (212). For Connell, to deny this is to deny the global reality of perduring inequalities, between the affluent and powerful 600 million living in the ‘centre’ and the poorer, less powerful 5400 million of the ‘periphery’.

‘Southern Theory’ in the Pacific and Asia?

I absolutely agree that we need to acknowledge global inequalities and the way these shape social theory. But we also need to reflect on the effects of our naming of such differences (Gibson-Graham). So I now explore the consequences of Connell’s preferred labels of ‘North’ and ‘South’, ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’. In my view, use of the language of the cardinal points of cartography to describe inequalities between nations or peoples tends to naturalise and dehistoricise difference, to associate the points of the compass with the body habitus of up and down, left and right. Clearly this is at odds with Connell’s avowed aim to stress relationality between peoples and the changing contexts of power and knowledge across time and place. So, although I endorse Connell’s prophetic vision of an inclusive and worldly social theory (cf. Curthoys and Ganguly), I am rather more wary about deploying geopolitical labels which derive from cartographic referents which themselves betray a deep imperial history.

In a recent overview of foreign and Indigenous representations of the Pacific (Jolly, “ Imagining Oceania”), I have counterposed ‘cartography’, grounded in imperial navigation and the hubris of Western ‘discoverers’ and Indigenous ‘genealogies’, which connect people not so much through the abstract logic of kinship detached from land (as for Lévi Strauss, see Connell, Southern Theory, 66-67, 196) but through the connection of people and place, the place of the ocean as well as the land, where Oceanic peoples were travellers on ‘routes’ as much as natives with ‘roots’. In that essay I also consider how the interpenetration of these views in the course of colonial history has yielded a ‘double vision’. While Pacific peoples have, arguably, adopted the powerful optic of Western cartography and the associated ethnological partitioning of Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia, this has not necessarily led to an eclipse of Indigenous visions.

My discussion here continues Connell’s exploration of ‘Southern theory’ but emphasises relationships of knowledge and power between Australia and the Pacific. This region, although clearly part of Connell’s ‘periphery’, is mentioned only in passing and through a brief narrative of the fate of Kahana valley on Oahu, Hawai’i (204-6), as part of a critique of settler colonialism in North America and Australia and ‘the silence of the land’ in global social theory (cf. Wolfe). In the Pacific we might witness not just the ‘silence of the land’ but the ‘silence of the ocean’ in contemporary cartographies configured by geopolitical influence.

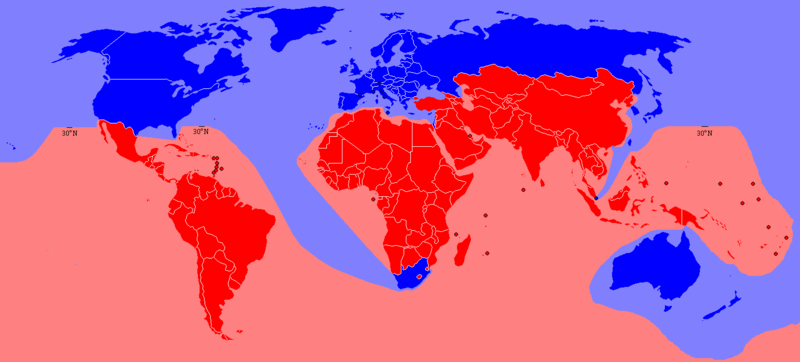

In previous papers dealing with Pacific feminisms and the language of human rights (Jolly “ Woman Ikat Raet ”and “Beyond the Horizon”), I observed how notions of ‘North’ and ‘South’ like ‘West’ and ‘East’ uneasily connect geographical cardinal points with geopolitical potencies. I further suggested that the language of universalism articulated by Pacific women is not heard as such because they are speaking from places seen as remote and powerless. The designations of North and South refer both to the hemispheres above and below the equator in a conventional Mercator projection of the globe, and the respective positions of rich and developed nations of Europe and North America and the poor and underdeveloped countries of Africa, Asia, South America and the Pacific (see Figure 1). Of course, no-one assumes the two are coincident—Northern and Southern hemispheres do not map inequalities of wealth and power between or within nations. But what is the effect of making such a link, and our embodied association with ‘up’ and ‘down’? The geographic/geopolitical coordinates of East and West are more laterally conceived, opposed like North and South, but less hierarchically conceptualised. The Middle East (Said) and the East of Asia have in EuroAmerican social theory, both past and present, often been seen as rival loci of ‘civilisations’, even if clamorously constructed as a ‘clash’ (Huntington) or as antithetical (as in representations of the ‘West’ in debates about Asian values,see Dirlik, “East-West/North-South”).

Figure 1: North-South Divide. Image courtesy of Wikipedia:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:North_South_Divide_3.PNG. Accessed 12 March 2008.

In such cartographic imaginaries Australia has often been presented as anomalous, a country of the ‘North’ in wealth, development and dominant intellectual genealogies but ‘South’ in latitude. Our antipodean location has often been exploited by those of us who want to challenge the hegemony of social theory from Europe and North America, in intellectual challenges which echo Australian anti-colonial sentiments about both British and American empires. Coming from the ‘South’ seems to have a rebellious resonance which coming from the ‘North’ lacks. It is a claim that many of us have made: it is a resonant refrain in Australian social theory, to combat the ‘metropolitan’ perspectives from New York or London as partial, even parochial. Indeed, some of Raewyn Connell’s most influential books on gender, masculinities and class (e.g. Ruling Class, Gender, The Men,Masculinities), though global in their reach, have been suffused and strengthened by a strong sense of antipodean location. In a rather more limited way, I have challenged the hegemony of North American visions of feminist anthropology in reflections on the politics of difference (see Jolly, ‘Our Part of the World’).

Yet adopting the position of ‘Southern’ theorist as a privileged Australian scholar might also distract from contributions to social theory from those who are more truly ‘Southern’ in ‘our part of the world’, for example Indigenous Australians, discussed in Southern Theory and Indigenous Pacific peoples, who are not. Before I explore what might constitute ‘Southern theory’ in the relations of knowledge and power between Australia and Pacific, let me briefly allude to the region with which the Pacific is often linked, to suggest both a comparison and a contrast: Asia.

In debates about Australia’s relation to Asia from the 1990s to the present many have observed that Australia isin but not of Asia and urged the importance of a revitalised engagement (Fitzgerald). With the recent election of the Rudd government in November 2007, the central importance of Australia’s relation to the Asian region is likely to focus not just on the present and future geopolitical weight of China and India but the urgent need for more Australians to familiarise themselves with the diversity of Asian languages, cultures and histories and hopefully to appreciate the ‘Southern theory’ emanating from such places. For India we have already witnessed the global influence of subaltern theorists, as discussed by Connell. The appreciation of ‘Southern theorists’ from China is perhaps less well developed in Australia, partly because they usually write in Chinese rather than English. Still, several books and films by Geremie Barmé and collaborators (New Ghosts, Old Dreams, Shades of Mao, In the Red, Gate of Heavenly Peace and Morning Sun) and a recent book by Gloria Davies, Worrying About China (2008), are important introductions to the character and complexity of contemporary social theory there, and the reconfiguration of foreign theories in a Chinese context.

In exploring Australia’s relation with the Pacific we might observe that as with Asia, we are seen as in but not of(see Jolly, “Imagining Oceania”). But the Pacific is far removed from such continental Asian giants as China and India, in terms of population, wealth and geopolitical influence. Increasingly the affluent countries and classes of Asia can no longer be construed as part of a ‘periphery’ in relation to an imagined EuroAmerican centre. But most of the Pacific is still perceived as peripheral—remote, underdeveloped, poor and weak—in dominant Australian representations, and in need of our aid and assistance. Over the nearly twelve years of the Coalition government, Australia’s involvement in the Pacific markedly increased, especially in Papua New Guinea (PNG) and the Solomons, with dramatic interventions in situations of political turbulence and threat, and in saving states from ‘failing’. Such interventions regularly raised questions about sovereignty and neo-colonial influence (e.g. see Kabutalaka on RAMSI in the Solomons and Dinnen on PNG) but reinscribed the ‘special relation’ which Australia sustains with PNG, its erstwhile colony, and with several proximate countries of the southwest Pacific.

In what follows I will consider the rival regional imaginaries of ‘Asia-Pacific’ and ‘Oceania’ and the way they differentially imagine the relations of knowledge and power between Australia and the Pacific and the place of ‘Southern’ social theorists. Then, I consider how these different optics are materialised not just in the texts of scholars but in visual and performance arts displayed at the Asia-Pacific Triennial of Art at the Queensland Art Gallery and the Oceania Arts Centre at the University of the South Pacific. In Southern Theory, Connell for the most part confines her attention to texts, since ‘it is only written texts that allow sustained argument and systematic critique’, the capacity for self-reflective knowledge and ‘communication of complex social knowledge across planetary distances’ (xii).1 Yet elsewhere in that volume she allows that Indigenous Australian art embeds a social theory (Chapter 9) and celebrates how this is creatively deployed in a study of contemporary rock music by Vivien Johnson (Radio Birdman). It is my contention that social theory in the Pacific has been embedded not just in scholarly texts such as those of Epeli Hau’ofa discussed below but, as in Indigenous Australia, embodied in visual arts, oratory and dance (see Katerina Teaiwa “Visualizing Te Kainga” and “Learning Oceania”).

Contending Imaginaries of Region: Oceania and Asia-Pacific

There are different visions of the Pacific, rival regional constructs, which I encode as ‘Oceania’ and ‘Asia-Pacific’. These names are not just innocent reflections of cartographic realities but, as Gibson-Graham attest, such naming produces real effects in the world. So we might pause to ponder the origins and effects of these different words.

The word ‘Oceania’ has a long and complex colonial genealogy, exhaustively researched in recent time, especially by scholars in Australia and France (Clark “Dumont D’Urville’s”; Jolly “Imagining Oceania”; Tcherkézoff, Thomas, In Oceania). The insights of this literature might be briefly distilled. First, the cartographic referents of Oceania have been historically fluid, shifting from the epoch of European ‘discoveries’ through later periods of conquest and settlement. In its original articulation by Dumont d’Urville in 1835 and in the map of Océanie (attributed to Levasseur) it embraced the islands of the Pacific (divided into Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia) and Australia and the Malay peninsular. In many later iterations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these Asian and Australian edges fell off the map. Second, foreign perspectives on ‘Oceania’ have shifted with the different lens of contending British, French, North American and Japanese imperial visions (see Endo Framing, Matsuda, Wilson Reimagining). Third, such foreign visions were not just colonial mirages but became sedimented in Pacific places and in the minds and bodies of its peoples as in indigenous appropriations of sub-regional labels: ‘the Melanesian way’, ‘the Polynesian triangle’, ‘the Micronesian world’ (see Jolly “ Imagining Oceania”, Narokobi).

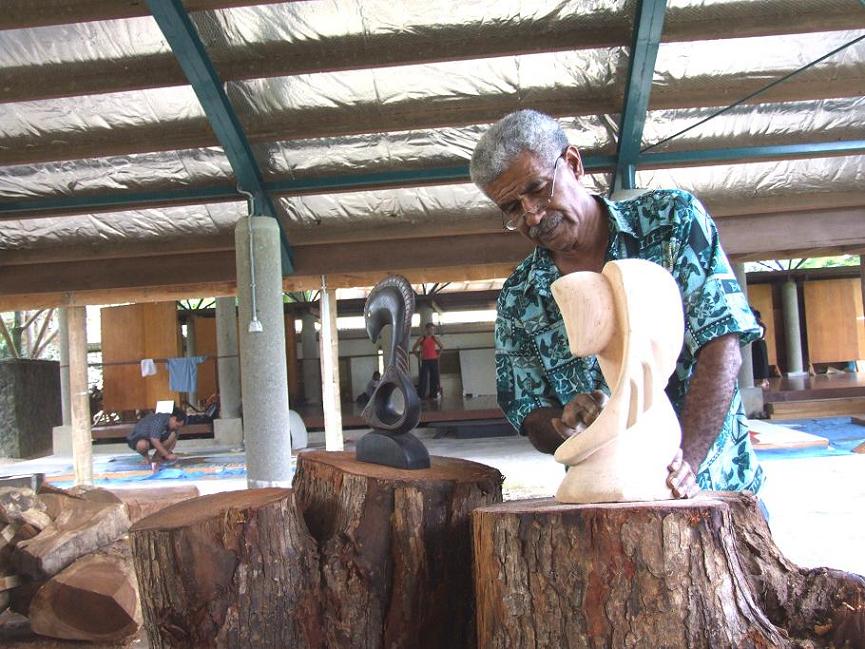

The generic colonial label, ‘Oceania’, has been reclaimed and revalorised by the Tongan scholar Epeli Hau’ofa (“Our Sea”) in a visionary reconceptualisation of the embodied life experiences of Pacific peoples and the intellectual work of Pacific Studies (see Hau’ofa We are the Ocean and Figure 2). We might thus see him as a quintessential ‘Southern theorist’. In a series of influential articles (“Our Sea”, “The Ocean”, and “Epilogue”), he critiqued the prevailing developmentalist and geopolitical models of the Pacific as discursively diminishing their small scale, lack of development and isolation from each other. He refocused attention not just on the small islands and atolls of land but the connecting ocean. He highlighted Oceanic cosmopolitanism, ‘world travellers’ traversing the region in the ancient past and the present, connecting Pacific peoples in the islands with the countries of the Pacific Rim. He critiqued the colonial partitioning of Pacific peoples into Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia and the associated rhetorical stress on roots rather than routes as defining of indigeneity (see Clifford “Indigenous Articulations”, Routes, Jolly “ On the Edge”). Hau’ofa defied essentialist views of culture and reified notions of tradition, by advocating cross-cultural exchange, mixing and creolisation, a vision realised in the innovative Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture established at the University of the South Pacific from 1997 (see below). Figure 2: Epeli Hau’ofa. Photograph by Ann Tarte. Image courtesy of Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture.

Figure 2: Epeli Hau’ofa. Photograph by Ann Tarte. Image courtesy of Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture.

Hau’ofa’s prophetic visions have been much debated: some have stressed how centuries of colonialism also catalysed new cultural flows (with sail and steamships and the turbulent waves of Christian conversion); some have argued that his conception of Pacific peoples as world travellers and overseas migrants is skewed towards Polynesians (see Jolly “ On the Edge”); some have seen his visions as utopian, given the stark realities of stalled development, poverty, inequality and violence in the contemporary Pacific. Yet such debate has probably only broadened and deepened his influence. Since the mid-1990s ‘Oceania’ has proliferated in the titles of scholarly books, conferences, cultural events, and Pacific organisations, especially in Hawai’i, in Fiji and New Zealand. But, especially in Australia, ‘Oceania’ confronts a pervasive rival in regional labelling, ‘Asia-Pacific’.

Hau’ofa was expressly critical of such prevailing regional labels of the late twentieth century: Pacific ‘region’ and ‘rim’ and ‘Asia-Pacific’, which he claimed portrayed the Pacific in terms of lack, as ‘the hole in the donut’ (”Our Sea”). Dirlik and his collaborators in the United States (Dirlik “The Asia-Pacific” and What is, Connery, Wilson and Dirlik 1995) were simultaneously mounting fierce critiques of these regional imaginaries whose origins they discerned in US foreign policy discourse from the mid-1970s. According to Connery, Pacific Rim discourse emerged during the late Cold War contention with the socialist bloc, when defeat in Vietnam, the ascendancy of Japan and economic decline threatened the United States. Pacific Rim discourse stressed connection and partnership between the United States and Japan (on the axis of West and East) but also nervously anticipated the emerging spectre of China’s power. Such discourses migrated to Australia, assuming a particular salience in the Keating period and beyond. During this time, there was passionate and sometimes agonised public debate about Australia being ‘in’ but not ‘of’ Asia (see Fitzgerald) and renewed reflection on Australia’s ‘special relationship’ to the Pacific (see Fry “Framing”).

Trenchant scholarly critiques have had little impact on the continued use of the term. ‘Asia-Pacific’ has moved far beyond its initial use as a geopolitical label preferred by certain economists and politicians, becoming the conventional regional language of many international organisations and NGOS, sporting events and carnivals, celebrations of the visual arts, and networks of Australian scholars who research in ‘area studies’ (e.g. at the Australian National University in the College of Asia and the Pacific where I work and across Australia in a network sponsored by the Australian Research Council, the Asia-Pacific Futures Research Network, in which I am involved). I am not criticising this conjoint emphasis on these two regions of the world nor the need for Australians to consider them both, or in relation to one another. But, in the Pacific, there has often been consternation at this yoking together of two such disparate regions, which seemed less about their historical relations (many and varied) but more about geopolitical visions from ‘beyond the horizon’ (Jolly “Beyond”). So we might ask, what is the effect of such naming and framing, what happens when Asia and the Pacific are so conjugated by a connecting hyphen?

Perceptions of the Pacific in Australia’s foreign policy in the Howard years were dominated by geopolitical questions about national and regional security, especially in those countries proximate to Australia which some dub ‘the arc of instability’ (see May et al) or portray as ‘failing’ or ‘failed’ states. Greg Fry (“A ‘Coming Age’”,Whose Oceania) has offered a critique of such an approach and has also advocated an approach to regionalism in which Australia might assume a less hubristic and agonistic posture. He observes that the processes of region-building and of state-building have been complicit in the colonial and postcolonial periods, and thus regionalism is not so much an alternative to state forms, but a parallel development, albeit with increased velocity since 2001. The idea of the Pacific region is for him materialised in regional organisations like the Pacific Community, based in Nouméa and the Pacific Islands Forum and the University of the South Pacific, both based in Suva. But, as Fry insists, regionalism is not just confined to those organisations which are congregations of states, but is articulated in broader social movements, embracing NGOs and church groups, human rights activists and environmentalists, and in the work of scholars, artists and performers (cf. Bryant-Tokalau and Frazer).

Moreover, contending visions of the Pacific pose the crucial question of ‘whose Oceania?’ (Fry Whose Oceania). Behind the seeming unanimity of the 2004 Auckland declaration by Pacific Islands Forum Leaders of a prophetic ‘Pacific plan’ he discerns large differences. At one extreme are Australian-led initiatives to deepen regionalintegration predicated on the idea of Australia’s ‘special responsibility’ to lead and the security imperative of the ‘war on terror’. At the other is a model proposed by Pacific leaders which valorises good governance, redressing poverty and deeper regional participation. For Fry, these contending visions have divergent moral and political legitimacy. His analysis again highlights the ambiguous and ambivalent perception of Australia, as in but not ofthe region (Whose Oceania).

But the dominant frame continues to be that of ‘Asia-Pacific’, in which Australia assumes a special responsibility to lead and not ‘Oceania’ where Australia might adopt a more modest position as an integral part of the region. It will be interesting to see what the recent election of the Rudd government will mean in terms of a different orientation to the Pacific. Early signs—especially the appointment of Duncan Kerr as Parliamentary Secretary for Pacific Islands Affairs, and Rudd’s visit to PNG in March 2008—augur well. But rather then speculate about the likely future directions of Australia’s foreign policy, aid and development in the region which others are far better qualified to do (and see Fry, Australia), I now ponder the rival labels of Asia-Pacific and Oceania as frames for the visual and performing arts, by comparing the Asia-Pacific Triennials at the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane and the Oceania Arts Centre in Suva, inspired and headed by Epeli Hau’ofa.

The Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art at the Queensland Art Gallery

The exhibition of cosmopolitan contemporary artists at the Asia-Pacific Triennials of Contemporary Art (APTs), from 1993 to 2006, is one of the more public and perduring attempts to envision ‘Asia-Pacific’ from an Australian perspective. Reaching out to the Pacific has perhaps been easier from Brisbane because of Queensland’s geographical proximity and colonial history: Torres Straits Islanders, South Sea Islanders, and migrants from New Zealand, Tonga and Samoa are part of large Pacific communities (some recently organised in a group called ‘Pan-Pacific Oceania’). The art selected for APTs was perforce ‘contemporary’ and came primarily from the vibrant Oceanic arts scene in Aotearoa New Zealand (especially John Pule, Michael Parekowhai, Michael Tuffery and Gordon Walters, see Thomas, Oceanic Art) and from Papua New Guinea (Michael Mel, Wendy Choulai). The inclusion of textiles created by women within this rubric of ‘contemporary art’ was problematic for some, but was especially prominent in 2006, in the superb Pacific Textile Project curated by Maud Page (see catalogue essays by Thomas, Page, Jeffries and Teaiwa in Seear and Raffell The 5th Asia-Pacific, 24-31, 172-183). These textiles included quilts by Aline Amaru from Tahiti, Emma Tamaril from the Marquesas, Tungane Broadbent and Tekauvai Teariki Monga from the Cook Islands, Gussie R. Bento and Deborah (Kepola) U Kakalia from Hawai’i, and woven pandanus textiles and baskets by Finau Mara from Fiji, Susana Kaafi from Tonga and Sivamauga Vaagi from Samoa, along with many unidentified textile artists. In 2006 these art works were complemented by a series of superb films by Sima Urale, a filmmaker of Samoan ancestry living in New Zealand (as part of an innovative cinema program created by Kathryn Weir) and a number of performances, floor talks and discussions by artists.

There is much to applaud about the Asia-Pacific Triennials and the selection and the display of Oceanic art has been particularly exciting and vibrant. Yet there are important questions posed by the regional frame. Francis Maravillas earlier argued apropos the ‘cartographies of the future’ of the fourth APT at the Queensland Art Gallery, that the missing third term, hidden under the hyphen, was Australia. The ‘curatorial imaginary’ was for him less characterised by regional liaison and exchange and more by a presumption of Australia ‘as a privileged curatorial subject, actively defining the conditions of regional dialogue and exchange, and its place at the centre of it’ (“Cartographies”, http://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/ari/conf2004/asianart.htm). Exhibition strategies rendered ‘invisible the power and privilege’ of Australians in assembling and legitimising works of contemporary Asian art. Similar tough questions have been posed apropos the fifth APT by Michelle Antoinette (‘On Collecting’). Earlier, Antoinette (Images) radically deconstructed the language of regionalism, arguing that South East Asian arts on display, especially at early APTs and contemporaneous exhibitions elsewhere, were often unduly seen through the lens of region, ethnicity and biography, occluding other themes—such as the body, mobility and memory—and even sometimes neglecting the aesthetic potency of the works as art in favour of cartographic curatorial interpretations.

These questions posed by Maravillas and Antoinette about Asian art at APTs can be extended, perhaps more forcefully, to Oceanic art. The fifth Asia-Pacific Triennial and the superb new Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), where many treasures of previous Triennials are exhibited, makes this question even more timely (see Figure 3). Oceanic art was highlighted in 2006; indeed the John Pule work Tutalagi tukumuitea (Forever and ever) features on the catalogue cover. But rather than focus on the aesthetic potency of works in APT5 by Pule and Parekowhai whose engagement with critical questions about European colonialism, Christianity, migration and memory, imperial power and translation, has been much discussed, I focus on the beauty and the power of textiles created by Pacific women and displayed in Brisbane in 2006.

Figure 3: Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), Brisbane. Photograph © John Gollings Photography.

Figure 3: Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), Brisbane. Photograph © John Gollings Photography.

Across Oceania, textiles are, as Teresia Teaiwa (“Keeping Faith”) proclaims, ‘precious things’, wherein the value of women’s creative work with threads and fibres is celebrated. Women textile artists are thereby keeping ‘faith’ both with their Christianity and indigenous cultural values. Different forms and styles signal diverse cultural origins—Hawai’i, Tahiti, Samoa, Fiji, the Cook Islands—but all these textiles alike embody and reflect upon the creolisation of indigenous and exogenous in the course of colonial history and Christian conversion. Indigenous fibres—like pandanus, bleached and/or dyed, plaited or looped, and bark beaten into tapa and dyed or decorated—were conjoined with novel forms—stitching cotton and silk with needle and thread and knitting or knotting wool (see Jolly “Of the Same Cloth”). But these conjunctions were not always benign hybrids. Introduced forms were often appropriated for Indigenous purposes and foreign genres deployed to anti-colonial ends.

Let us look at one example, the Hawaiian quilt, in which ‘techniques originally taught by American missionaries have been adapted to create inimitable textiles that appear to pulsate’ (Page, 172). The high-ranking women who were taught quilting by New England missionary women from the 1820s quickly transformed the dominant techniques of patchwork and the preferred motifs (snowflakes, log cabins). They favoured geometric patterns akin to indigenous tapa or dramatic representations of the sacred fertility of land and indigenous flora (breadfruit, taro, pandanus), created by folding and cutting to a template design, often using a striking palette of two coloured cloths (e.g. red on white, green on white, purple on gold). Like indigenous tapa, Hawaiian quilts were not just icons of cosy Christian conjugality but embodied the mana of ali’i nobility and especially the monarchy. The royal coat of arms was woven into nineteenth-century Hawaiian quilts and even became a sign of resistance when Queen Lili’uokalani was overthrown by American interests in 1893. As well as signing petitions for the return of the monarchy, Hawaiian women gathered around the Queen to create a giant silk patchwork quilt, emblazoned with their names and declarations of loyalty to royalty. Deborah (Kepola) U Kakalia’s stunning gold and purple quilt from 1993, displayed as part of APT5 in Brisbane, titled simply Lili’uokalani, evokes the poignant moment of the overthrow a century before, with central images of crowns and feathered standards, and an eight point star representing the Queen’s husband, all framed by the Queen’s favourite flowers of milkwood and fluttering fans (see Figure 4). This is not just a nostalgic lament for a lost past but an affirmation of sovereignty sentiments in opposition to the United States in a contested present.

Figure 4: Lili’uokalani (1993). Hawaiian quilt by Deborah (Kepola) U Kakalia. Collection: Bishop Museum Honolulu. Image courtesy of Bishop Museum Honolulu.

Figure 4: Lili’uokalani (1993). Hawaiian quilt by Deborah (Kepola) U Kakalia. Collection: Bishop Museum Honolulu. Image courtesy of Bishop Museum Honolulu.

Postcolonial cultural politics in practices of creolisation are apparent across a range of genres. From its inception the APT has included Oceanic cultural performances and more recently film screenings alongside exhibitions of paintings, sculptures and textiles. In Oceanic cultural festivals, the embodied art of dance has often been more important than exhibitions of visual arts detached from the body. Typically this has involved performances from dance groups from diverse islands, but as the history of the Festivals of Pacific Arts (previously South Pacific Arts Festivals every four years from 1972-2004) evinces these have not always been benign performances of regionalism (Hereniko, “Dancing Oceania”). ‘Disunity in diversity’ has been enacted in debates about authenticity and the appropriation of dance styles between islands. But, as Vilsoni Hereniko has shown, cross-cultural exchange and creolisation long evident in the visual arts and in Pacific literatures (see Hereniko and Wilson,Inside-Out), are now increasingly apparent in dance, most notably in the Oceania Dance Company based at the Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture in Suva, to which I now move.

The Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture in Suva

In contrast with the large, superb and costly edifice of Brisbane’s new Gallery of Modern Art, the Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture at the University of the South Pacific (USP) in Suva is a small if elegant and airy structure (see Figure 5). It is a sign of the differential wealth of Australia and the burgeoning business of art in this capital of Queensland, as against the relative lack of resources for such projects in Fiji, whose small and struggling commodity economy has been further weakened by the political turbulence of several coups from 1987 to December 2006. As Hereniko notes, the Oceania Centre was established in 1997 and Epeli Hau’ofa appointed Director only after several years of institutional struggle (“Dancing Oceania”). The administration of USP had a minimal interest in the development of arts and culture as against the formal academic programs where Hau’ofa had taught politics and development studies in the past. He was supported only by a program assistant and a part-time cleaner and allocated only a tiny budget for development. So, given the material constraints, the achievements of the Centre over a decade have been remarkable (see White “Foreword).

Figure 5: Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture, University of the South Pacific, Suva. Photograph by Margaret Jolly, July 2006.

Much of this has been due to Hau’ofa’s visionary leadership: the Centre embodies in aesthetic practice the vision of Oceania which Hau’ofa first developed in the several theoretical texts discussed above. Hau’ofa criticised how the expression of Pacific multiculturalism at USP too often emphasised cultural differences rather than affinities and cultural exchanges (“Epilogue”). In accordance with this philosophy, he advocated more mingling and exchange of cultural forms, rather than an array of arts which articulated essentialised ethnic identities. He thus moved beyond a ‘unity in diversity model’ of Pacific cultures to foster exchange between Pacific peoples at the University of the South Pacific: indigenous Fijian and Indo-Fijian, Solomon Islanders, Samoans, Tongans, ni-Vanuatu, Banabans and so forth and fostered a community of artists working between the several genres of visual arts, music, dance and literature (see Figure 6).2

Figure 6: Carver Paula Liga and senior artist Lingikoni Vaka’uta at work, with senior dancer Tulevu Soroakadavu practising in the background, at the Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture. Photograph by Ann Tarte. Image courtesy of Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture.

Figure 6: Carver Paula Liga and senior artist Lingikoni Vaka’uta at work, with senior dancer Tulevu Soroakadavu practising in the background, at the Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture. Photograph by Ann Tarte. Image courtesy of Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture.

Let me offer some impressions of an exemplary performance designed by choreographer Allan Alo for the conference Vaka Vuku held at the University of the South Pacific in Suva in July 2006. In a statement in the final plenary of that event Allan celebrated his unique fa’afafine3 identity, as neither male nor female, loved and respected by his Samoan family and his community, not denigrated as are some who cross genders in the West. We saw a video of the several painful days in which he acquired his pe’a, the tatau iconic of hegemonic Samoan masculinity and cultural survival. Yet, in the final dance performances which he choreographed we witnessed the creative creolisation of Celtic and Pacific forms, in stunning, zesty moves, which flowed effortlessly from River Dance to the Oceanic (see Figure 7). They concluded with a brilliant dance by women dressed in white, men dressed in black and other more ‘feminised’ men, in the middle, in sinuous silver sulus. Dance styles alternated between masculine, feminine, and fa’fafine modes, with suggestive brushings and conjugations between different couples. The remarkable erotic energy, fluidity and virtuosity thrilled the audience. Sitting amongst a packed audience Epeli Hau‘ofa nodded with approving relish.4

Figure 7: Oceania Dance Company performing Fenua, September 2006. Choreographer Allan Alo. Photograph by Ann Tarte. Image courtesy of Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture.

Figure 7: Oceania Dance Company performing Fenua, September 2006. Choreographer Allan Alo. Photograph by Ann Tarte. Image courtesy of Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture.

So we see in these two contexts the embodied materialisation of two contending visions, one in Brisbane framed by ‘Asia-Pacific’ and the other in Suva by ‘Oceania’. The contrast suggests how rival regional frames can influence how works of art are created, seen and interpreted. It also reveals significant differences between the two contexts. In the first Australia assumes a strong and well-resourced authority, even responsibility, to bring together art from the Asian and Pacific regions, including Australia and New Zealand. Whether the sequence of the Asia-Pacific Triennials has also catalysed significant exchanges or collaborations between Asian and Pacific artists beyond their congregation every three years is a question that might be asked and further researched. In the more modest circumstances of Suva, regional relations were rather constructed between Oceanic peoples, without Australian curatorial mediation or funding, and the stress was firmly on collaboration and mutual exchange.

Narrative Threads in a World of Texts

But you might ask how do such aesthetic performances by Pacific people relate to Connell’s arguments inSouthern Theory? Clearly performative utterances in silken threads and sinuous bodies in dance cannot engage in the ‘sustained argument and systematic critique’ nor the ‘communication of complex social knowledge across planetary distances’ (xii), which for Connell is the hallmark of social theory. I am of course not suggesting that such artifacts or performances are akin to scholarly texts nor that they are aspiring to articulate meta-narratives of global relevance, as do some social theories. Yet ideas about what it is to be human and what ‘culture’ or ‘the social’ means in a post (or neo?) colonial and globalised world were surely subtexts of these materialisations.5Moreover, such vivid examples of artistic creativity reaffirm what Connell’s text highlights, that being ‘peripheral’ does not entail passivity or powerlessness and that material poverty sometimes co-exists with cultural vibrancy and intellectual élan. Moreover, in witnessing these visual arts and performances in both Brisbane and Suva, I learnt from artists and audiences engaged in passionate and self-conscious reflection, perhaps in languages that are accessible more widely than those of scholars like us who are most at home in a world of texts.

Professor Margaret Jolly is Head of the Gender Relations Centre in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. She has published extensively on gender and sexuality in the Pacific, with a particular focus on visual arts and literature. Her next book examines race, gender and sexuality in feature and documentary films about the Pacific.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Raewyn Connell for her book which prompted this essay and to Epeli Hau’ofa, Katerina Teaiwa and Greg Fry for their intellectual and artistic inspiration. Thanks again to Michelle Antoinette for great comments on substance and style. Thanks to the anonymous readers for their generosity. Finally thanks to Monique Rooney for the invitation, her meticulous editorial work and especially for her patience in waiting for my revisions in a very busy period.

Notes

1 This downplays the wealth of oral, visual and embodied knowledge as cumulative rather than critical and reflexive, oddly denigrating both non-literate cultures and the importance of such modes of knowing in audio-visual and global electronic media.

2 Given that Fiji has not even embraced multiculturalism this move towards mixing seems both provocative and optimistic. One of the extraordinary features of Fiji’s colonial history has been the ideological suppression of the realities of mixing between peoples: Europeans and Fijians, Chinese and Fijians, even Indians and Fijians. But perhaps in his prophetic way by plotting mixtures of the imagination, minglings in the domain of beautiful things, Hau’ofa may also be advancing the prospect of a mixing of peoples in Fiji, a transculturalism which goes further than any multiculturalism imagined to date.

3 Fa’afafine means “acting like a woman” in Samoan and refers to gender liminal persons born men but acting as women. It parallels Tongan faka’leiti analysed by Besnier.

4 This paragraph repeats a paragraph in my Introduction to a volume on Oceanic masculinities, where this is told in another context (Jolly “ Moving Masculinities”).

5 Both Thomas (“Our History”) and Jeffries (“Texts and Textiles”) read these textiles as texts, narrating cultural histories and propounding identifications through threads of narrative. Jeffries (“Texts and Textiles”, 180) notes that text and textile alike derive from the Latin texere, to weave. See Jolly, “Of the Same Cloth”, for a critical consideration.

Works cited

Antoinette, Michelle. Images that Quiver. The Invisible Geographies of ‘Southeast Asian’ Contemporary Art. PhD diss., Australian National University, 2006.

—. ‘“On Collecting”: The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art.’ Artlink 27.1 (2007).http://www.artlink.com.au/articles.cfm?id=2933 Accessed 14 March 2008.

Barmé, Geremie. In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

—. Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1996.

— and Linda Jaivin, eds. New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices. New York: Times Books, 1992.

Besnier, Niko. ‘Transgenderism, Locality and the Miss Galaxy Beauty Pageant in Tonga.’ American Ethnologist29.4 (2002): 534-566.

Bryant-Tokalau, Jenny and Ian Frazer, eds. Redefining the Pacific? Regionalism Past, Present and Future. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2006.

Clark, Geoffrey. ‘Dumont d’Urville’s Oceanic Provinces: Fundamental Precepts or Arbitrary Constructs?’ Journal of Pacific History Special Issue 38.2 (2003): 155-161.

Clifford, James. ‘Indigenous Articulations’. The Contemporary Pacific (Special Issue: Native Pacific Cultural Studies on the Edge). Ed. Vicente M. Diaz and J. Kehaulani Kau’anui. 13.2 (2001): 468-490.

—. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Connell, R.W. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1987.

—. Masculinities. 2nd edn. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

—. The Men and the Boys. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000.

—. Ruling Class, Ruling Culture: Studies of Conflict, Power and Hegemony in Australian Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

—. Southern Theory. The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2007.

Connery, Christopher L. ‘Pacific Rim Discourse: the US Global Imaginary in the Late Cold War Years.’ Boundary 221.1 (1994): 31-56.

Curthoys, Ned and Debjani Ganguly, eds. Edward Said: The Legacy of a Public Intellectual. Melbourne:Melbourne University Press, 2007.

Davies, Gloria. Worrying About China: The Language of Chinese Critical Inquiry. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Dinnen, Sinclair. Law and Order in a Weak State: Crime and Politics in Papua New Guinea. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001.

Dirlik, Arif. ‘The Asia-Pacific Idea: Reality and Representation in the Invention of a Regional Structure.’ Journal of World History 3.1 (1992): 55-97.

—. ‘East-West/North-South/Inside-Out: Thinking About Culture and Cultural Conflict in the Pacific.’ Framing the Pacific in the 21st Century: Coexistence and Friction. Ed. Daizaburo Yui and Yasuo Endo. Tokyo: Center for Pacific and American Studies, University of Tokyo, 2001. 2-28.

—. What is in a Rim? Critical Perspectives on the Pacific Region Idea. Boulder: Westview Press, 1993.

Dumont d’Urville, Jules-Sebastien-Cesar. Voyage Pittoresque Autour du Monde. Paris: L. Tenré and Henri Dupuy, 1835. Vol 2.

Endo, Yasuo 2001. ‘Japan’s Self Portrait Reflected in the Ocean.’ Framing the Pacific in the 21st Century: Coexistence and Friction. Eds. Daizaburo Yui and Yasuo Endo. Tokyo: Center for Pacific and American Studies, University of Tokyo, 2001. 49-69.

Fitzgerald, Stephen. Is Australia an Asian Country? Can Australia Survive in an East Asian Future? St Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 1997.

Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.

Fry, Greg. A ‘Coming Age of Regionalism’? Contending Images of World Politics. Eds. Greg Fry and Jacinta O’Hagen. London: MacMillan Press, 2000.

—. ‘Australia in Oceania: a “new era of cooperation?”‘ Australian foreign policy futures: Making middle power leadership work. Canberra: Department of International Relations, Research School of Asian and Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, 2008.

—. ‘Framing the Islands: Knowledge and Power in Changing Australian Images of “the South Pacific”’. The Contemporary Pacific 9.2 (1997): 305-44.

—. Whose Oceania: Contending Visions of Community in Pacific Region-Building. Working Paper 2004/3. Canberra: Department of International Relations, Research School of Asian and Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, 2004.

The Gate of Heavenly Peace. Produced and Directed by Carma Hinton, Geremie Barmé and Richard Gordon. Long Bow Group, 1995.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays, London: Hutchinson, 1975.

Gibson-Graham, J-K. ‘Area Studies after Post-Structuralism.’ Environment and Planning A 36.3 (2004): 405-419.

Giddens, Anthony. Runaway World: How Globalisation is Reshaping Our Lives. 2nd ed. London: Profile Books, 2002.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. Empire. Cambridge MA: Harvard UP, 2000.

Hau’ofa, Epeli. ‘Our Sea of Islands’. The Contemporary Pacific 6.1 (1994):148-161.

—. ‘The Ocean in Us’. The Contemporary Pacific 10 (1998): 391-410.

—. ‘Epilogue – Pasts To Remember’. Remembrance of Pacific Pasts: An Invitation to Remake History. Ed. R. Borofsky. Honolulu: U of Hawai’i P, 2000. 453-471.

—. We Are The Ocean. Selected Works. Honolulu: U of Hawai’i P, 2008.

Hereniko, Vilsoni. ‘Dancing Oceania: The Oceania Dance Theatre in Context’. The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Ed. Lynne Seear, Lynne and Suhayana Raffel. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, 2006. 32-41.

—. and Rob Wilson, eds. Inside-Out: Literature, Cultural Politics and Identity in the New Pacific. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999.

Huntington, Samuel P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Jeffries, Janis.‘Texts and Textiles: Pacific Encounters’. The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Ed. Lynne Seear and Suhayana Raffel. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, 2006. 180-183.

Johnson, Vivien. Radio Birdman. Melbourne: Sheldon Booth, 1990.

Jolly, Margaret. ‘Beyond the Horizon? Nationalisms, Feminisms, and Globalization in the Pacific’. Ethnohistory(Special Issue Outside Gods: History Making in the Pacific) 52.1 (2005): 137-66.

—. ‘Imagining Oceania: Indigenous and Foreign Representations of a Sea of Islands’. The Contemporary Pacific19:2: 508-545. Revised and updated version of Framing the Pacific in the 21st Century: Coexistence and Friction. Ed. D. Yui and Y. Endo. Tokyo: Center for Pacific and American Studies, U of Tokyo, 2001. 29-48.

—. ‘Moving Masculinities: Memories and Bodies Across Oceania’. The Contemporary Pacific (Special Issue: Re-Membering Oceanic Masculinities). Ed. M. Jolly. 20.1 (2008):1-24.

—. ‘Of the Same Cloth?: Oceanic Anthropologies of Gender, Textiles and Christianities’. Distinguished Lecture. Association for Social Anthropology in Oceania Conference, Australian National University, 14 February 2008.

—. ‘On the Edge? Deserts, Oceans, Islands’. The Contemporary Pacific (Special Issue: Native Pacific Cultural Studies on the Edge). Ed. Vicente M. Diaz and J. Kehaulani Kau’anui. 13.2 (2001): 417-66.

—. ‘“Our Part of the World”: Indigenous and Diasporic Differences and Feminist Anthropology in America and the Antipodes’. Communal/Plural 7:2 (1999): 195-212.

—. ‘Politics of Difference: Feminism, Colonialism and Decolonisation in Vanuatu’. Intersexions: Gender/Class/Culture/Ethnicity. Ed. G.Bottomley, M. de Lepervanche and J. Martin. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1991. 52-74.

—. ‘Specters of Inauthenticity’. The Contemporary Pacific 4:1 (1992):49-72.

—. ‘Woman Ikat Raet Long Human Raet O No? Women’s Rights, Human Rights and Domestic Violence in Vanuatu’. Human Rights and Gender Politics: Asia-Pacific Perspectives. Ed. A.-M. Hilsdon, M. Macintyre, V. Mackie and M. Stivens. London and New York: Routledge, 2000. 124-46. Updated and expanded version of article first published in Feminist Review 52 (1996): 169-90

Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius Tara. ‘Australian Foreign Policy and the RAMSI Intervention in Solomon Islands’. The Contemporary Pacific 17.2 (2005): 283-308.

Maravillas, Francis. ‘Cartographies of the Future: The Asia-Pacific Triennials and the Curatorial Imaginary’. 2004. http://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/ari/conf2004/asianart.htm

Matsuda, Matt K. Empire of Love: Histories of France and the Pacific. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005.

May, Ronald J. et al. “Arc of Instability”?: Melanesia in the Early 2000s. Canberra: State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Project, and Christchurch NZ: MacMillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies (Occasional Paper No 4), 2003.

Morning Sun. Produced and Directed by Carma Hinton, Geremie Barmé and Richard Gordon. Long Bow Group, 2003.

Narokobi, Bernard. The Melanesian Way: Total Cosmic Vision of Life. Boroko: Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies, 1980.

Page, Maud and Ruth McDougall‘Pacific Textiles Project, Pacific Threads’. The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Ed. Lynne Seear and Suhayana Raffel. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, 2006. 172-175.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon, 1978.

Seear, Lynne and Suhayana Raffel, eds. The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, 2006.

Slater, David. Geopolitics and the Post-Colonial: Rethinking North-South Relations. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

Strathern, Marilyn. The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia.Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

Tcherkézoff, Serge. ‘A Long and Unfortunate Voyage toward the Invention of the Melanesia/Polynesia Opposition (1595-1832)’, Journal of Pacific History 38.2 (2003): 175-96.

Teaiwa, Katerina. Visualizing Te Kainga, Dancing Te Kainga. History and Culture Between Rabi, Banaba and Beyond. PhD diss, Australian National University, 2003.

—.‘Learning Oceania – A Vision for Pacific Studies at the ANU’. Keynote Lecture, Asia-Pacific Week, The Australian National University, Canberra, January 2007.

Teaiwa, Teresia. ‘Keeping Faith and the Nation: Pacific Textiles’. The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Ed. Lynne Seear and Suhayana Raffel. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, 2006. 176-179.

Thomas, Nicholas. In Oceania: Visions, Artifacts, Histories. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997.

—. Oceanic Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1995.

—. ‘Our History is Written in Our Mats: Reflections on Contemporary Art, Globalisation and History.’ The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Ed. Lynne Seear and Suhayana Raffel. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery Publishing, 2006. 24-31.

White, Geoffrey. ‘Foreword’. In We Are the Ocean: Selected Works by Epeli Hau’ofa. Honolulu: U of Hawai’i P, 2008.

Wilson, Rob. Reimagining the American Pacific: from South Pacific to Bamboo Ridge and Beyond. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2001.

—. and Arif Dirlik, eds. Asia/Pacific as Space of Cultural Production. Durham and London: Duke UP, 1995.

Wolfe, Patrick. Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. London and New York: Cassell, 1999.