By Lesley Instone

© all rights reserved. AHR is published in PDF and Print-on-Demand format by ANU E Press

Encountering the fence-line

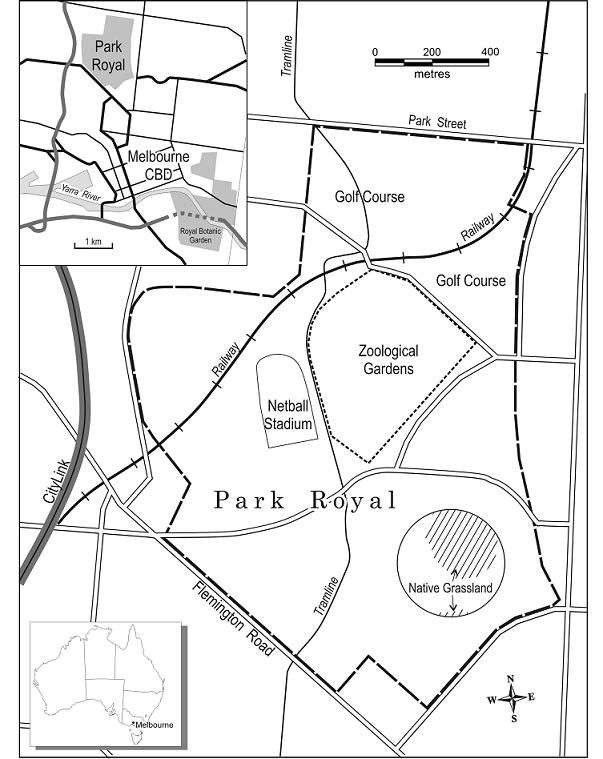

This paper begins at an unexpected fence enclosing a large area of native grassland in an inner urban Melbourne park (Photo 1). Royal Park at 188 ha is Melbourne’s largest park, and its southern corner is about 3 km from the CBD (Figure 1).

The fence is located on a hill, sometimes referred to as the dome; an iconic treeless feature, encircled by a path it rises slightly above the surrounding parkland, commanding striking views of the city to the east (Photo 2). On one side of the fence green lawn stretches out across the parkland, pleasing to the eye and unremarkable in its ubiquity (Photo 3). On the other, in the enclosed area, native grasses rise up tall and yellow (Photo 4). These are kangaroo and wallaby grasses re/established to reference the original vegetation of the treeless grassy plains of the western Melbourne area (Photos 5 and 6). The fence is an arresting delineation of native/non-native, introduced/indigenous, colonial/postcolonial. The contrast between inside and outside is stark—green/yellow, mown/unmown, neat/messy, familiar/unfamiliar, accessible/inaccessible, alien/native. The green lawn side references the expected urban park landscape. The other side looks more like a country paddock (although even in the countryside it would be rare to find such a stand of native grasses).

When I first stumbled across the fence and enclosed native grasses I was perplexed and intrigued. Here was a plant species—native grasses—that, in ecological and historical terms, belongs in this place, yet in the urban park setting and enclosed behind a fence, it looked utterly out-of-place. The fence not only halted my walk across the dome, but captured my interest, intersected my movement and my train of thought. I was provoked to slow down and pay attention (Bingham 111-112) and to query the parkscape norm. The field of native grasses is a disconcerting scene as most inner Melbourne parks, especially long established and inner urban ones such as Royal Park, are carpeted in a sea of green (exotic) turf.1 Sweeps of lawn came to dominate park landscapes early in Australia’s colonial history (Holmes, Martin and Mirmohamadi 70-72) and, as Schama notes, ‘Turf, acre after acre of it, became the landscape of settled civility’ (qtd. in Holmes, Martin and Mirmohamadi 70). The lawn is the traditional setting for picnics, healthy exercise, and the many activities and bodily stances that have historically been fostered as ‘proper’ in urban park space (Holmes, Martin and Mirmohamadi, ‘Chapter 4′).

Coming upon the fence and tall native grasses proved an ‘awkward encounter’ (Hitchings), as the native grassland suggests the possibility of another kind of urban park, another landscape, different relations, other bodily stances, and other natures. There is a gate into the grassland, and it’s captivating to walk among the beautiful kangaroo grasses and the taller, now in midsummer, yellow wallaby grass. You can immerse yourself in the novelty and pleasure of such an experience, but it’s one tinged with a visceral anxiety engendered by the possibility of snakes and lurking danger. The fence and grasses trigger a bodily and conceptual sense of unease, a dissonance, a provocation to re-think and to walk differently. In another context, Koori writer and historian Tony Birch contemplates how the Number 55 tram that runs through Royal Park follows ‘a route once familiar to Wurundjeri people travelling to Mt William—traversing the plain just to the east of the Moonee Ponds Creek and Coonan’s Hill’ (397). He gazes (on a tram journey in 2001) at the few eucalypts in the park, not as representations of a previous landscape, but as witnesses to these earlier ‘comings and goings’ across this space (397). Following Birch’s line of thought, the Royal Park grasses reference not just the ‘natural, native, original’ landscape of western Melbourne, but previous human-plant-place relations, colonial dispossession, and other modes of connection between humans and nonhumans. The plants as witness may well have a very different tale to tell than the stories of native versus alien that dominate ecological restoration in Australia today.

Native nature, park nature

There is by now a considerable literature on issues of ‘nativeness’, ‘invasives’, ‘exotic’ and belonging in relation to the management and restoration of Australian parks and landscapes. Authors have pointed to the cultural contingencies and historically shifting meanings that underpin these debates (Head and Muir ‘Nativeness’; Robbins ‘invasive networks’; Kull and Rangan; Jacobs; Trigger ‘native vs. exotic’; Griffiths), and highlight the ‘sliding scales and blurred boundaries’ (Warren 432) that beleaguer attempts at definitive categorisation. Here, I set the Royal Park grass story in motion in the mid-1980s with the rise of an ecological nativism whereby pre-1788 plant distributions were taken as defining what was ‘truly’ native. This vision of local nativeness contends that only plants that occurred in a particular area prior to European settlement were considered to belong to that place. As Geoff Carr, a Melbourne-based botanist interviewed in 1985, put it so polemically, ‘now we’re into a new era where we realise that importing [into Melbourne, that is] Western Australian banksia or hakea is much the same as bringing in a magnolia from China or a yew from Europe (in Clarke 462). This shift in attitude focused attention on invasive species and ‘environmental weeds’ (Low ‘feral futures’; Morton and Smith; Carr; Kuelartz and van der Weele; Clark; Head and Muir ‘Nativeness’), advocating that ‘native plants that have spread beyond their natural range within Australia’ can be considered unwanted and environmentally compromising weeds (Groves qtd. in The Weed Society of NSW, my emphasis). Such categorisation set new benchmarks for environmental restoration, and framed it within the discourses of econationalism in the popular imagination (Franklin; Head and Muir ‘Nativeness’). Such foundational narratives, based on a questionable and colonial notion of what is ‘natural’, redraw and unwittingly rigidify the lines of the native/alien debate in Australia by structuring environmental narratives within Eurocentric discourses of a pristine, purified and timeless precolonial nature, and create new geographies of whiteness in putatively postcolonial settings (Hage; Dunlap; Jacobs; Head; Anderson ‘white nature’; Rose).

In recognition of these concerns, attention has turned to the contingencies and corporeality of plants (Head and Atchison 237) and the embodied encounters through which humans engage with them (Hitchings and Jones; Zagorski, Kirkpatrick and Stratford; Hitchings; Head and Muir ‘Suburban life’). Likewise, Kull and Rangan shift focus from the normative dimensions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ inherent in the native/non-native debate, and instead, explore questions of ‘how’ and ‘why’: that is, ‘how and why a plant becomes imbricated in regional landscapes and how human sensibilities emerge in concert with the plant’ (1271). We can understand these new approaches as akin to Bruno Latour’s quarrel against purified categories (We have never been modern), a position that he pushes further by advocating the elimination of the categories of both nature and society (see Politics of nature) as a necessary strategy for sidestepping the fence-line of definitional disputes and the aporia of what Val Plumwood terms hyperseparation (Plumwood Feminism and the mastery of nature).

Instead of trying to make a bridge between nature and society, Latour suggests another sort of move, one he characterises as a ‘moving sideways’ and ‘going with the flow’. Moving sideways and going with the flow take us into the messy, mixed up and mobile experience of being in an unstable ‘middle’ space that is neither nature nor culture. ‘It is the same world’, says Latour ‘and yet, everything looks different’ (Latour, ‘What is the style…’ 39). Rather than two incommensurable sides of nature/society or native/alien, Latour plunges us into a world of encounter and mediation where there are only naturecultures. For Latour’s mobile body, the fence becomes a line of communication, not just a system of division (Carter 13). Far from being stationary and fixed the fence is a dynamic space of contestation and interaction that activates all manner of work (Instone ‘fences’; ‘dingoes’). At the heart of Latour’s sideway move is the shift in register from ‘matters of fact’ to ‘matters of concern’:

A matter of concern is what happens to a matter of fact when you add to it its whole scenography, much like you would do by shifting your attention from the stage to the whole machinery of a theatre. (Latour, ‘What is the style…’ 39)

In this paper I take up Latour’s challenge to shift attention to ‘the whole scenography’ of an event and pay attention to the multiple practices and materialities that are assembled and enacted in the re/introduction of native grasses in Royal Park. This includes the work of restoration and re/introduction of native species, the work undertaken to make the park look ‘natural’, as well as the work that it takes to both make and maintain the separation of native/non-native categories so evident at the Royal Park fence-line.

Anthropologist David Trigger and colleagues argue that changing and contested dispositions towards nativeness and belonging inform practical decisions about ecological restoration, conceptually and materially (Trigger, Mulcock, Gaynor, and Toussaint). They emphasise that ecological restoration is not a straight-forward singular activity, but a complex and shifting set of socio-cultural concerns that shape the claims to nativeness of particular species. They suggest three cultural frames of ecological restoration (1274):

• Restoration as re-naturing and re-valuing—enhancing a biophysical environment by reintroducing ‘native’ species—e.g. the native plant movement;

• Restoration as removal—attempting to return an environment to an earlier state by removing exotic species—e.g. cane toads;

• Restoration as re-conceptualisation—conceptual restoration through processes of reinterpretation, repatriation or claiming of species as native—e.g. the dingo.

Here, I extend and re-read Trigger et al’s dispositions of ecological restoration in the light of Latour’s provocation to matters of concern, not as cultural frames but as a bundle of unevenly distributed practices involving re-naturing, revaluing, removal and repatriation which each enact shifting relations between native/non-native, nature/culture and constitute different modes of what ‘restoration’ might be with divergent effects. Such contested notions are evident in urban park restoration projects where a complex mix of revaluing previously unwanted plants (eg. mangroves (McManus), removing plants identified as weeds or invasives, and reconceptualising the spatial parameters of belonging for some species (for example seeing native grasses as belonging in urban areas) are evident. Further, I draw upon work in relational geographies that question the ontological separation of plants and people (Head and Atchison 236; Whatmore; Hitchings and Jones). These geographies insist, as Haraway so nicely puts it that ‘beings do not predate their relatings’ (‘Companion species’ 6). In other words people, plants and restoration activities can be understood as emergent in the practices, relations and entanglements that adhere in particular places and at particular times. My argument is that grasses and grasslands are multiple and unfixed entities that come into being through the assembled practices of a range of actors—human and nonhuman—and that shift in relation to the broader assemblages that constitute them. Taking account of the co-presence of grass in the practices of restoration and re/introduction highlights not just the agency of nonhuman others, but the affective qualities of nonhuman presence and the embodied nature of the practices that shape and are shaped by such encounters.

This paper began at the fence with the moment of disconcertment (Verran) that sparked my curiosity. Science and Technology Studies (STS) scholar Helen Verran welcomes such affective moments of pleasure and confusion, suggesting that they are openings in which to figure difference in another way. Further, she notes that ‘These fleeting experiences, ephemeral and embodied, are a guide in struggling through colonising pasts, and in generating possibilities for new futures’ (5). In what follows I trace the plethora of practices, presences, encounters and contexts that constitute the re/introduction of native grass species in Royal Park, focusing particularly on the enactment of naturalness and nativeness in urban park space, and the historical contingencies that give rise to particular configurations of people-park-plants in a particular place.

Grass tales

The vegetation of the volcanic plains of Victoria is characterised by grassy ecosystems and grassy woodland, and these ecosystems are now one of the most endangered in Victoria (Williams, McDonnell and Seager). These plains sweep westward from what is now Melbourne, and were among the first areas to be settled by European colonisers. This section of the plains is the home of the Wurundjeri people for whom the western grasslands provided good hunting and gathering in precolonial times (Presland). But the grasslands, and the area that Royal Park now occupies, were soon appropriated for sheep grazing, then later, in 1845, set aside for parkland and open space by Governor La Trobe (Donati; Holmes, Martin and Mirmohamadi 143). Despite this, the area was neglected and sheep continued to be the main occupiers until the 1860s when 20 hectares of land were granted for a zoological gardens (Donati). About the same time, the park hosted large crowds to witness the departure of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition to navigate a passage from south to north across the continent.

Governor La Trobe’s lasting legacy for Melbourne is the ring of parklands that surround the city, of which Royal Park is one. Yet all of these parks have been whittled down in size over the years, none more so than Royal Park, which now occupies only a third of the area it was in 1885 (Sexton and Reilly). The edges of the park have been carved away by various excisions to house State institutions (past and present) including a high school (1929), children’s (1957) and dental (1963) hospitals, youth detention centre, scientific research centre, and commonwealth games athletes’ village (2006) (Whitehat). Further, excisions for suburban development and expanded allocations for the zoo and associated car parking, have shrunk the park to its current size (RPPG, ‘Whatever happened’). The park was used as a temporary army camp during WWI, and again in WWII when it was used by US military forces, and known as Camp Pell. Subsequently the camp was converted to emergency housing until around the late 1950s when it was demolished in preparation for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics (Urban Camp). Only one building remained, and this was converted to become an Urban Camp for country children in 1984 (Urban Camp). Various busy roads and a tramline run through the park. The park has recently come under threat from pressures of urban expansion and freeway development and a new Children’s Hospital is currently under construction (RPPG, ‘Whatever happened’ and ‘Under threat again’).

Sports infrastructure was first introduced to Royal Park in 1903 with the establishment of a golf course, followed at later dates by sports fields, pavilions and car parks. These became contested uses of the park, engendering debate as to the place of sporting facilities in contemporary urban parkland. This debate flared most recently when the state government proposed to build a hockey and netball stadium as part of the state’s bid for the 2006 Commonwealth Games (Munro). In the past, the term ‘park’ applied to cleared open spaces and reserves used for sports and as sportsgrounds (Whitehead, ‘Parks and gardens’), but more recently parks have been appreciated for their natural qualities and for different forms of recreation. The history of Royal Park calls into question what a park is, what uses can legitimately take place there, what counts as an acceptable park landscape, and who and what the park is for. It highlights the shifting imaginaries—ecological, aesthetic and cultural—of urban parkland across time and between different, often competing, groups.

The vegetation in what remained of the open space areas of Royal Park has been extensively cleared, grazed, modified, graded and grassed, and variously ‘improved’ over the years. However, it appears that Royal Park was not ‘improved’ in the manner of the other parks that LaTrobe set aside, many of which displayed elaborate plantings of exotic trees, garden beds and formal layouts (Whitehead, ‘Civilising’).2 There had been some planting of native trees in the 1930s, a time when ‘nationalistic sentiments and the desire for Australian flora were high’ (Donati). However, it wasn’t until the late 1970s that resident opposition to proposed commercial activities in the park led to the development of the ‘Royal Park Landscape Masterplan’, 1977 (AILA, ‘Masterplan’). This Masterplan included a small native garden to be established in a corner of the park (AILA, ‘Masterplan’) not far from where the native grassland is now located. The Masterplan proposed bush regeneration, cycle paths, picnic facilities, road closures and opposed the expansion of sporting facilities. None of these proposals were implemented at that time (AILA, ‘Masterplan’).3 Continuing debates over the changing uses and nature of the park, failed planning attempts, and resident agitation about incessant incursions of other uses into the park, prompted the Melbourne City Council to hold a design competition for the park in 1984.

The winners of the 1984 design competition aimed ‘to create a coherent, informal pattern of dominant eucalypts in a naturalistic woodland, crowned with the hill covered in native grasses’ (AILA, ‘Competition’). At the same time they stressed the impossibility of a fixed and finished landscape, and devised a ‘living landscape’ design that would ‘support a changing community’ and ‘gradually evolving activities and elements of the landscape’ (AILA, ‘Competition’). They referenced their design on their reconstruction of the ‘landscape that confronted the first European settlers’. Their vision was premised on divining the ‘essential’ qualities of that landscape and creating a place that seemed natural (AILA, ‘Competition’). The first step in this process of restoration was to rid the park of what they termed ‘horticultural clutter’. In the context of the new nativist planting scheme such ‘clutter’ included deciduous trees, palms, pines and the like (AILA, ‘Competition’). Yet, this was no uncompromising restoration, native versus alien restoration plan. Indeed Strafford and Jones, the authors of the winning plan, wanted first and foremost to recreate the atmosphere and look of a ‘natural’, pre-contact landscape. To do so they were willing to include ‘apparently native vegetation’, avoid native plants that looked too exotic, and use non-native plants if they added to the natural ambience of the park (AILA, ‘Competition’). In their plan for a restored Royal Park, a naturalised landscape was to be achieved by way of a hybrid planting scheme. In doing so their plan eschewed a seamless elision between nativeness and naturalness. ‘Plantings’, they said, ‘should seem natural to the place, but do not need to be limited to indigenous species’ (AILA, ‘Competition’, my emphasis) thus bringing a visual rather than ecological priority to the project.

The centrepiece of the 1984 vision for Royal Park was the clearing of the large hilltop, or dome, to create a ‘spacious quality’ and ‘reveal … a vast sky’. The hill was to be delineated by a circular path and planted ‘as a sea of grass’ (AILA, ‘Competition’) swaying and rippling and crowning the hill surrounded by naturalistic woodland. The designers saw native grasses as superior to introduced grasses in that they ‘require less maintenance and water than introduced grasses’ (AILA, ‘Competition’). The choice of a cleared, elevated site for the grassland was ecological as well as aesthetic. For the grassland to be self-regenerating it needed full sun, isolation from invasive roots and water-borne weed seeds, and to be away from excessive foot traffic. An irrigation system would help establish the new plantings and reduce flammability.

At the time, the design was a bold and radical move (Munro). On the one hand it was a romantic vision where the designers, quoting Thoreau, imagined an open sky and swaying grassy fields: ‘Sweeping like waves of light and shade over the whole breadth of (the) land … ‘ (Henry David Thoreau) (AILA, ‘Competition’). In this vein, referencing the picturesque tradition, the designers wanted the park to appear unstructured and unplanned, and their design relied on a notion of the hidden hand of the designer to create an apparently spontaneous and natural landscape. On the other hand, the proposed expanses of native grassland raised the spectre of a park without cool green grassy lawn, a wounded park from which non-native trees would be ‘ripped-out’ (the term popular in news reports), decimated sports ovals turned over to native grassland, and other such action counter to the conventional European image of urban parkspace in Melbourne.

Domesticating native grass

The native grassland depicted in the fence image I started with may have resulted from the design competition. Its entrance into Royal Park in the late twentieth century echoed changing appreciations of Australian nature, increasing interest in growing Australian native plants, urban environmental movements and community actions towards restored urban environments and urban conservation. The 1970s saw the first serious consideration of the use of native grasses in urban parkland, driven by the National Capital Development Corporation, a body established in 1957 to develop new satellite suburbs to house Canberra’s growing population. Canberra was established on extensive grassy plains and the resulting ‘bush city’ was heavily influenced by the garden city movement. It may have been the confluence of these features with nationalistic desires that sparked the interest in using native grasses in low-use parkland, as well as along roadsides and verges (Anon). Hampered by the lack of knowledge about sowing, harvesting, germination and maintenance, the NCDC in 1973 funded the CSIRO to conduct experimental research investigating the parkland potential of four native grasses, including kangaroo and wallaby grasses (Anon). Canberra’s City Park Administration also set up trial plots. The team gathered data on germination, water requirements, management of established grasses, weed control, extolled the potential of native grasses in urban spaces, and developed a set of guidelines for parkland use of native grasses (Anon; Powell; Hagon, Groves and Chan).

This scientific work articulated discourses equating ‘nativeness’ with ‘naturalness’, where naturalness is figured as harmony with the natural environment (Trigger, Mulcock, Gaynor, and Toussaint 1276). The benefits of native grasses are thus described in terms of ‘adaptation’, and ‘unique qualities’ such as drought resistance and no need of fertiliser. ‘Fit’ with the environment was also emphasised through the claim that native grasses—as ‘natural’—needed little maintenance especially compared to introduced grasses (Hagon, Groves and Chan; Anon; Power). The scientists also reflect a re-valuing of Australian vegetation, occurring in the 1970s, with all mentioning their ‘attractive appearance’ (Hagon, Groves and Chan 11) and promoting aesthetics as a major advantage of native grasses. Later Stuwe (a botanist from La Trobe University) goes as far as to note:

A neatly manicured, traditional lawn in a supposedly natural bush setting can look rather absurd. The rich greens of introduced grasses clash violently with the more sombre tones of much of the Australian bush. (40)

Such an impassioned rejection of exotics and their comparability with natives points to the complex imbrication of scientific and cultural categories in ecological restoration in Australia. The early native grass research program demonstrates a mix of socio-cultural and scientific factors at work in re-valuing native nature, and bringing native grasses into popular use (Trigger, Mulcock, Gaynor, and Toussaint). In this sense, the scientific work was as much about helping to redefine what belongs in park space as it was about plant ecology and production. The winning Royal Park design built on the enthusiasm and vision of this early scientific work and took an optimistic stance that the re/establishment of grasses was feasible and that once established would be stable, cheaper and less work to maintain (AILA, ‘Competition’).

Such optimism was built on the ecological nativism imaginary that if a plant is in its ‘proper place’ then it will flourish and look after itself, and in the park context that native plants require few inputs, little maintenance, and are hence cost-effective. Such an imaginary assumes that the material properties of grass are fixed, and that landscapes tend to stable, steady state environments. However, as I have argued, grass is not a singular entity, and it is only the intense work of park managers and their institutions that hold park nature, lawns, native grasses and all, in the specific configurations that are recognisable as a park landscape. Lorimer, for example, notes that urban parks are ordered into an artificial equilibrium and managed to appear as stable, idealised climax communities (2050). In the Royal Park context, in order to hold the new native grass landscapes in place, park managers have had to develop new practices of control and management to ameliorate the problems posed by native grasses in urban settings, such as the need to burn or slash and bale grasses, weed control, invasion by exotics, and their vulnerability to trampling. It has proved difficult to mix species due to divergent seed germination requirements (Hitchmough 453), and plantings have often been limited by the availability of commercial quantities of seed (Stuwe 42; Hitchmough). Ironically, the development of commercial seed has involved the domestication of species and concerns have been raised regarding genetic conservation (Hitchmough 449). As well, a species such as Austrodanthonia (wallaby grass) is a poor competitor as a seedling, and different grasses have varying susceptibility to herbicides. It’s not surprising that attempts to re/create grasslands have generally been small scale and hampered by a lack of horticultural capability (Stuwe 42).

Making the Royal Park grasslands

After three years of deliberation Melbourne City Council adopted Stafford and Jones’ design in principle (Munro). But it took another four years before grassland plantings were commenced in 1991 in accordance with the designers’ intentions. In Royal Park, the large area of native grassland enclosed by the fence occupies part of what was once the WWII Camp Pell military camp, and subsequently emergency housing until around 1960, when it was cleared. It was later utilised as a car park, sports field and associated pavilion (Mawditt).4 These uses left the area bereft of any indigenous vegetation. The initial area for planting the native grasses was intended to be the highest part of the dome, but due to a surveying error, this is not the case. In 1991 the small area that was once the car park was planted with kangaroo grass and this was expanded in 1999. In 2003 irrigation was installed and the fence erected prior to sowing 35,000 kangaroo grass (Themeda) cells. Most of these, however, were pulled out by ravens looking for insects and other food. Another planting of 2.4 ha in early 2004 also failed and had to be sprayed out with a non-selective herbicide due to weed growth. A few months later 1.6 ha of wallaby grass (Austrodanthonia) was sown. A later phase of plantings commenced in September 2005. Broad spectrum weed control was deployed and the area was irrigated. Again, success was elusive and the area was re-sown in May 2006 to fill-out thin areas. The work on the site brought asbestos fragments to the surface from the bull-dozing of the military camps, and the site had to be cleaned up in late 2006 and the asbestos removed.

The efforts to establish the grasses has involved site preparation, installation of an irrigation system, mowing and bailing, soil nutrient control, weed control for broadleaf weeds and weedy perennial grasses once or twice a year and annual hand removal of Chilean Needle Grass and Serrated Tussock (Mawditt). The fence was erected to prevent public access due to the regular and consistent herbicide weed control program and to protect seedlings. It’s outlived its use and was meant to be removed in 2007, but so far no action has been taken (Mawditt). As Paul Robbins points out in his work on the American turf grasses, a range of human and nonhuman actors need to be assembled in the act of creating a lawnscape, and these are greatly influenced by culture and politics (Robbins, ‘How grasses’ 140). Likewise, the complex mix of people, plants and technologies at Royal Park highlights the socio-technical assemblage of scientific inquiry, horticultural practices, commercial nursery industry, multinational chemical industry and state power, that intermingles with the belief that native grasses are better adapted, more natural and require little maintenance. The re/introduction of native grasses at Royal Park called for the cultures of re-valuing (involving community desires and political will from the city council to implement the winning design), practices of removal (involving weeds, herbicides, various other chemicals, human labour), and the work of re-naturing (involving the nursery industry, private management firms to undertake the plantings and maintenance work, irrigation systems, top dressing, mowers). As well, the grasses themselves, ravens, and the like, exerted their agency in often surprising and obstinate ways. In many ways, the restoration efforts failed to take account of the grasses themselves—they became design elements and horticultural objects of trial and error, imagined as singular, stable and passive entities. All these practices, institutions, human and nonhuman actors have to be assembled and that assemblage maintained to re/create even a monocultural grassland such as that at Royal Park.

Grasses coming and going

While the scientists and landscape designers may have been enthusiastically promoting native grasses, their proposed introduction in 1984 at Royal Park was met with some spirited opposition. In many sections of the community native grasslands have a poor image, are envisioned as ‘simple’ ecosystems (Ross), lacking aesthetic value and appeal (Williams and Cary). Detractors of the Royal Park winning design highlighted the ‘ripping out’ of exotic and deciduous trees and the removal of sports fields as acts of vandalism ‘wrecking perfectly good parks and gardens’ (Blunden 12).5 Further, they accused the winning design of breaking the ‘covenant’ that a park is ‘for the recreation of the people’ (Grant 12). This latter view draws on long standing anthropocentric conventions that ‘parks are for people, not for plants’ (Meserow 11). Human-plant relations in parks have historically been invested with moral significance (Holmes, Martin and Mirmohamadi, ‘Chapter 4′; Goodman 404) and charged with the ‘important role in civilising and “improving” the citizens’ (Holmes, Martin and Mirmohamadi 10). In this sense, plants in public parks are not just a neutral backdrop, nor even there for their own right, but are carefully placed and selected species that are figured as instructive, health-giving, and morally-enhancing. The plants and their arrangements are perceived as playing an important role in forging suitable citizen bodies worthy of belonging to the nation (Holmes, Martin and Mirmohamadi 130). The control of nature and the citizen are figured as a simultaneous achievement.6

Urban parks have historically been about the ordering and control of nature as an exemplar for the ordering and control of human bodies (Holmes, Martin and Mirmohamadi, ‘Chapter 4′). So the introduction of ‘nativeness’ and a ‘wilder’ less controlled, or less controllable nature introduces not just a challenge to park managers, but a challenge to the existing social and urban order. It undoes the park as a consummate space to encourage horticulture and civilise the populace (Goodman 404). It gestures towards disorder, or at least a different order of the urban, and concomitant ‘new’ urban citizens. Indeed, the winners of the 1984 competition saw their design as expressing ‘the particular character of this place’ which they linked to a notion of a ‘freely thinking people’ (AILA, ‘Competition’). They appear to draw on econationalistic sentiments to build an alliance between naturalness, informal plantings, movement and the character of the populace, perhaps envisioning that a native-style landscape would both mirror and build a relaxed Australian citizen body, a sort of home-grown identity in line with the proposed home-grown look of the park.7

More than this, the opposing view that native grasses are incompatible with urban parks figures native grass as an alien and invasive plant (in a cultural rather than ecological sense). Environmental philosopher Val Plumwood encountered enmity towards native grassland when she tried to protect a small area in a NSW country town cemetery. Plumwood’s efforts came to nought against the desires of local people for a neatly mown Europeanised landscape. In such public spaces, Plumwood argues that ‘[t]he war against nature aims to eliminate independent agency, and is waged under the banner of tidiness, order and respect’ (64). ‘Natives’, she suggests, ‘disrupt rigid, instrumental categories of control’ (64). Certainly at Royal Park the re/introduction of native grasses was seen as invading the ‘proper grass’ and ‘proper uses’ of the park, and images of snakes escaping from the grassland and disrupting cricket matches were used to engender fear of disorder and chaos in the park and to highlight the displacement of humans from their rightful public space. The grasses caused consternation by moving from passive backdrop to demanding their own presence, and decentring the conventional image of the human as the active subject of park space.

Grassy matters of concern

By paying attention to the multivalent story of native grass in Royal Park, what looked like matters of fact begin to soften, to

render a different sound, they start to move in all directions, they overflow their boundaries, they include a complete set of new actors, they reveal the fragile envelopes in which they are housed. (Latour, ‘What is the style…’ 39)

The matters of fact that appeared ‘indisputable, obstinate, simply there’ (‘What is the style…’ 39)—the ‘facts’ that native grasses are better suited to Australian park environments, that they are more natural and therefore need less attention and artificial chemicals, and so on—have been revealed as disputable and uncertain. In the move to matters of concern we witness the shift from native grass as a landscape feature representing precolonial nature, to grass as a relational achievement, emergent in varying assemblages, and co-produced by many actors. Native grass is no longer a singular, discernable category or an object of manipulation ‘where nature is divided into manageable parts’ (Verran 72), but thickly entangled in heterogeneous networks of people, chemicals, animals, irrigation technology, insects, institutions, place, time, socio-cultural values and ecologies, to name a few.

In the mobile swirl of moving sideways, matters of concern ‘carry you away’, says Latour, and they have to be ‘appreciated, tasted, experimented upon, mounted, prepared, put to the test’ (‘What is the style…’ 39). In other words, matters of concern matter. The wily, uncooperative grasses at Royal Park demanded attention. My encounter with fence and grass in Royal Park carried me along between pleasure and disconcertment, and raised the question of how we might coexist with park nature as active, unexpected and enlivened (Hitchings and Jones 15). As a matter of concern, the proliferation of native grasses upsets the previous constitution of urban parks, what they should look like, and who or what they should be for, and opens to visibility the presence of others, suggesting a more-than-human park of active engagement. And like my perplexing, albeit ordinary, everyday encounter with the Royal Park fence and grasses, matters of concern are embodied and affective. They focus our attention on ‘difference as located in banal routines of ongoing action’ (Verran 38).

If you enter Royal Park along a small path from Bayles’s Street you’ll come upon a smaller, more diverse planting of native grasses, that follows the path along the southern edge of the dome (Photo 7). This area was developed in 2002 to show what indigenous grasslands would have looked like and involved a community planting of over 6000 tubes (Mawditt). The diversity of grasses gives it a more naturalistic feel than the fenced area, but like its big cousin it has involved site preparation, weed control and on-going maintenance. As a consequence of its open edges and proximity to the path, the area is degraded by trampling from dogs and humans, and requires about 200 new plants each year (Mawditt).

These grasses have a distinct presence in relation to the fenced area and they elicit different performances from humans. People often slow their step here and may be observed to stop and linger or to pick some grass stalks. There’s no fence here, and no sweeping vista across swaying grasses, just a small planting, accessible to mobile park bodies (human and nonhuman). It could be the more domestic scale and feel, the greater diversity of the grasses, the lack of fencing or the community relations that created the grassland, that engender a different encounter between humans and native grass here. This area is pretty, accessible, safe, more garden-like and domesticated compared to the wilder more unruly expanses further across the dome.

Two proximate areas of native grassland, two different naturecultures, each stitched into different, but overlapping, assemblages and relations. The same grasses, but different, each enacting a different proposition of the relation between people, park and grass. Pondering this difference brings me to Latour’s suggestion that we encounter the native grasslands as a proposition; that is, as a new entity, not as a recreation of an old one, or as Latour would have it, a novel nonhuman/human assemblage of native grasses, involving park managers, city council, local residents, dogs, ravens and others.8 The proposition of a field of native grass cannot be considered in isolation, but rather as one entangled in wider networks. In this account the grasses have no innate essence for that would arbitrarily close down the conversation across the fence far too quickly (Latour, ‘Politics of nature’). Labelling the grasses native/non-native and assigning value and worth along these dimensions leaves us stranded in a politics of my side/your side, battle lines drawn, defending a position, competing stakeholders and the demand for certainty. The questions of ‘is the grass native’ and ‘is it endemic’ are far too simplistic and only give us the answer of the dividing fence. Instead of seeing the grasslands as examples of ecological restoration, Latour encourages us to envision a new proposition that upsets the previous constitution of how humans and native grasses should be knotted together in park spaces. As such, it is a provocation of perplexity among many actors.

Perplexity for Latour requires that we resist any arbitrary simplification, trying instead to grapple with the cacophony of voices—human and nonhuman—that constitute a situation. Perplexity exposes ‘the conditions, forces and potential that might be activated within a proposition’ (Ripley, Thun and Velikov 6). As a relation of perplexity, the grasses pose a host of questions: Can we live with this new proposition of native grassland? How do we make room for, and how do we situate native grasses in the urban order? For these questions there is no ready answer, no categorisation into good/bad, native/non-native, no preordained value. The new proposition of native grasses also engenders work to be done; it sets things in motion and brings disparate things into articulation. For example, the native grasses require the work of ecologists, nurseries, and scientists to figure out how to grow, produce and maintain native grasslands in contemporary urban environments. They require the work of local councillors to persuade dog owners and sports people to accept them, along with the work of understanding the relations of care needed to tend native grasses in park spaces. And so on. The grass and fence join together a heterogeneous assemblage that stretches from the park to laboratories and chemical plants, from dog walkers to plant nurseries, from local government authorities to private park management firms, and from local residents to sports people and others who use the park facilities. But more than this, native grasses activate the work of finding new ways to live in colonised landscapes. In this sense, Latour’s notion of ‘matters of concern’ might help enact different possibilities of native/non-native relations that facilitate postcolonial times and places.

Conclusion

Latour suggests that we no longer inhabit a world (if we ever did) of smooth objects, with clear boundaries, objects firmly embedded in the world of facts and untouched by politics or culture. Instead he suggests a world of tangled objects with risky attachments where we are enmeshed in complex networks in which we ‘can no longer be detached from the unexpected consequences that they may trigger’ (Latour, ‘Politics of nature’ 24). As a risky attachment, the Royal Park grassland draws us into a number of matters of concern, including the use of herbicides and other chemicals in practices of re/introduction and maintenance work, the place of sport in contemporary urban life, the desire for a return to originary nature, the place of humans in the park, the fight to keep public lands, research funding policies, and the politics of shrinking grasslands in the face of urban expansion. As such it enacts not one ecological politics of native vs. alien, belonging/not belonging, but a multiple politics of naturecultures and uncertainty that can ‘catch us off guard’ (Latour, ‘Politics of nature’ 25). Back at the fence we can understand a different relation than that of division and dualism, instead considering the fence as enacting an encounter, a space of conjunction and the possibility of a sideways movement across and along. From this perspective, other forms of connectivity more attuned to uncertainty, context, situation and multiplicity, more open to earthly others and lively encounters, may serve us better. Following Tony Birch, we may wish to re/orientate ourselves to pastpresents9 (Haraway, When Species 292) through modes of witnessing, for example, that are open to other presences and non-visual forms of knowing. As Deborah Rose notes: ‘to hear is to witness; to witness is to become entangled’ (Rose, ‘Reports’ 2004).

The design winners for Royal Park tried hard to enact a ‘living environment’ of changing nature, yet notions of stability, in nature and history, crept in to scupper their vision and create an ambiguous outcome. My encounter with the Royal Park fence and urban grassland provoked disconcertment and the question of how to respond to complex issues of human-plant relations in colonised settings without re-enacting dualistic division or repeating foundational narratives. Throughout the paper I have endeavoured to hang onto that affective moment as a provocation to perplexity and openness. The rich particularities and complexities of the Royal Park grassland story remind us that what matters is the precise how of entanglements (van Dooren). Modes of entanglement that refuse dualistic categorisation will need to be nurtured in the search for reparative practices that enact alternate management regimes and urban park design choices. The fence in the guise of dualistic division embodies a moral choice between native and alien, anchoring parkspace within the deeply sedimented humanist tradition of human exceptionalism. Yet, moving through the Royal Park grassland, we can apprehend other possibilities. The park, grass, fence, perplexity, body and affect, as matters of concern, can nudge us towards an ethics of co-transformation, postcolonial ecologies and multispecies encounter. Anna Tsing imagines ‘a human nature that shift[s] historically together with varied webs of interspecies dependence’ (Tsing qtd in Haraway, When Species 218), a proposition that tugs us bodily into entanglements of people and plants as mutually constituting networks that are constantly becoming, open-ended and historically contingent. Not just one native grassland but multiple ones, manifested through different and on-going sets of nested relations.

Shrinking native grasslands and urban park grass re/introduction projects deserve our attention as matters of concern, not as representatives of an idealised past or as resources for an idealised future. Matters of concern force us to pay close attention to what is going on, and slow us down enough to encounter a problematic and pleasurable space full of uncertainties (Stengers 144-5 qtd in Bingham 116), a curious and perplexing space in which we can reorient ourselves to multispecies coexistence with the dry grasses scratching our legs. Moving sideways from the twin poles of nature and society ‘frees us to perform new expressions’ of coexistence in the here and now (Muecke 8), and enact postcolonial possibilities of how we might better live together. The practices of proposition and perplexity take us only to the first base of an ecopolitics of matters of concern.10 But my goal here has been to map out the human-plant relations in urban parks as ‘matters of concern’, as a first step towards revealing the park as a multispecies site of inhabitation and negotiation—neither culture nor nature—neither a ‘park for people’ nor an open space delivering ecosystem services. Something richer and more interesting is going on.

Lesley Instone teaches in geography and environmental studies at the University of Newcastle, Australia. Her work focuses on Australian naturecultures and engages more-than-human and performative approaches. Her current research explores material and embodied encounters among humans, nonhumans and technology in urban park spaces.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Philip Mawditt, Royal Park Officer, for providing information on the planting of the grassland at Royal Park. Any errors or omissions remain the author’s responsibility. Thanks also to Jane M Jacobs whose insightful comments have improved the paper, and to Helen Verran for inspiration and conversations. I gratefully acknowledge both the School of Philosophy, Anthropology and Social Inquiry, Melbourne University and the School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh who hosted me as a visiting scholar during much of the research and writing of this paper.

Notes:

1 The photos of Royal Park were taken in December 2009 after good rains that followed a decade long drought in Melbourne. Many grasses brown off in summer in Australia, so the maintenance of green park lawns (and private ones too) in a dry continent continues to be a topic of much discussion and debate in Melbourne.

2 Yet inside the Zoological gardens formal garden beds were established.

3 The native garden was later established in a corner of the park, close to where the native grassland is now located.

4 The information in this paragraph as been kindly supplied by Phillip Mawditt, Royal Park Officer, Serco Australia.

5 At the close of 1984 there was much consternation regarding conservation and heritage issues in Melbourne. At the same time as the changes to Royal Park were in the media, the Melbourne City Council (MCC) released a conservation report authored by Rex Swanson, which was seen, among some sections of the population, to threaten the garden heritage of Melbourne’s older parks, particularly the Fitzroy and Treasury Gardens. One of a number of letters in the media complained that the council was planning to ‘sweep them clean and reform them to today’s ideas’ (Eager 12), a claim disputed by Swanson and the MCC. The Draft State Conservation Strategy was also released at this time. It suggested a conservation role for urban parks, further adding to concerns that prioritisation of natural/native environments would undermine the historical and heritage values and uses of existing urban park space. The endorsement, in an Editorial in The Age newspaper of creating Royal Park as an ‘urban forest’ added further fuel to the debate (The Editor 13).

6 Indeed, as Anderson notes: ‘The narrative connections that existed in the minds of British colonists between the activities of cultivating the land and settling were the key pillars underpinning the project of colonisation in Australia’ (Anderson, ‘Race and the crisis’ 92).

7 Likewise, Paul Robbins (‘How grasses’) in his study of grass in American domestic lawnscapes, argues that the practices of maintaining grass as turf/lawnscape interpellates a certain subject.

8 Latour’s suggestion resonates to some extent with Tim Low’s (‘New nature’) concept of a ‘new nature’ of mixed native and alien species assemblages, and the emerging concept of ‘novel ecosystems’ (Hobbs et al). ‘Novel ecosystems’ refers to ecosystems emergent in a human-modified world that differ from past and present configurations. These landscapes are neither historic or hybrid, but new ones which challenge current conservation and restoration practices. Both ‘new nature’ and ‘novel ecosystems’, however, still rely in varying ways on an ontological separation of humans and nature.

9 Haraway uses ‘pastpresents’ to describe the knotting in and around each other of pasts, presents and futures.

10 Latour’s ecological politics involves two powers; the power to take into account (the practices of proposition and consultation) and the power to put into order (the practices of hierarchy and institution) (see Latour, ‘Politics of nature’).

Works Cited:

Anderson, Kay. ‘White natures: Sydney’s Royal Agricultural Show in post-humanist perspective.’ Transactions, Institute of British Geographers, 28 (2003): 422-441.

—. Race and the Crisis of Humanism. London: Routledge, 2007.

Anon, ‘Growing native grasses in urban parks.’ Ecos 11 (1977): 29-31.

Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) ‘The Royal Park Competition.’ Landscape Australia 2 (1985): 134-140. http://122.252.1.79/projects/VIC/RoyalPark/winner01.htm Accessed 8 Dec. 2009

—. ‘The Royal Park Landscape Masterplan Competition.’ Landscape Australia 3 (1985): 227. http://122.252.1.79/projects/VIC/RoyalPark/problems.htm Accessed 8 Dec. 2009

Bingham, Nick. ‘Slowing things down: Lessons from the GM controversy.’ Geoforum 39 (2008): 111–122.

Birch, Tony. ‘Returning to country.’ A museum for the people: A history of Museum Victoria and its predecessors, 1854–2000. Ed. Carolyn Rasmussen. Melbourne: Scribe Publications, 2001. 397-400.

Blunden, R. ‘Uprooting of park trees is vandalism.’ Letters to the Editor, The Age 15 Dec. 1984: 12.

Carr, G. W. ‘Australian plants as weeds in Victoria.’ Plant Protection Quarterly 16, (2001): 142-145.

Carter, Paul. ‘Lines of Communication: Meaning in the Migrant Environment.’ Striking Chords: Multicultural Literary Interpretations. Ed. S. Gunew & K. O. Longley. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1992. 9-18.

Clark, Nigel. ‘The Demon-Seed: Bioinvasion as the Unsettling of Environmental Cosmopolitanism.’ Theory, Culture & Society 19.1–2 (2002): 101–125.

Clarke, Neil. ‘Reading the Plants.’ Meanjin 47.3.Spring (1988): 458-467.

Donati, Laura. ‘Royal Park’ eMelbourne: the city past & present, 2008. http://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM01282b.htm Accessed 8 Dec. 2009

Dunlap, T. R. Nature and the English Diaspora: Environment and History in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Cambridge: Cambridge U Press, 1999.

Eager, L.F. ‘Think carefully before changing city gardens.’ Letters to the Editor, The Age Dec. 13 1984: 12.

Franklin, Adrian S. Animal Nation: The True Story of Animals and Australia. Sydney, UNSW Press, 2005.

Griffiths, Tom. Hunters and Collectors: The Antiquarian Imagination in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge U Press. 1996.

Goodman, David. ‘The politics of horticulture.’ Meanjin 47.3, (1988): 403-12.

Grant, A.G.A. ‘Park purpose’ Letters to the Editor, The Age 14 Dec. 1984:12.

Hage, Ghassan. White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society. Annandale: Pluto Press Australia, 1998.

Hagon, M. W., R. H. Groves, and C. W. Chan. ‘Establishing native grasses in urban parkland.’ Australian Parks and Recreation Nov. (1975): 11-14.

Haraway, Donna J. T he Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

—. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2008.

Head, Lesley, and Jennifer Atchison. ‘Cultural ecology: emerging human-plant geographies.’ Progress in Human Geography 33.2 (2009): 236-245.

Head, Lesley, and Pat Muir ‘Nativeness, invasiveness and nation in Australian plants.’ Geographical Review 94.2 (2004): 199-217.

—. ‘Suburban life and the boundaries of nature: resilience and rupture in Australian backyard gardens.’ Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers NS 51 (2006): 505-24.

—. Backyard: nature and culture in suburban Australia. Wollongong: U of Wollongong P, 2007.

Head, Lesley. Second Nature: The History and Implications of Australia as an Aboriginal Landscape. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2000.

Hitchings, Russell, and Verity Jones. ‘Living with plants and the exploration of botanical encounter in human geography research.’ Ethics, Place and Environment 7.1 (2004): 3-18.

Hitchings, Russell. ‘How awkward encounters could influence the future form of many gardens.’ Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 32.3 (2007): 363-376.

Hitchmough, J. D. Urban Landscape Management. Sydney, Inkata Press, 1994.

Hobbs, Richard J., Salvatore Arico, James Aronson, Jill S. Baron, Peter Bridgewater, Viki A. Cramer, Paul R. Epstein, John J. Ewel, Carlos A. Klink, Ariel E. Lugo, David Norton, Dennis Ojima, David M. Richardson, Eric W. Sanderson, Fernando Valladares, Montserrat Vilà, Regino Zamora and Martin Zobel. ‘Novel ecosystems: theoretical and management aspects of the new ecological world order.’ Global Ecology and Biogeography 15 (2006): 1–7.

Holmes, Katie, Susan K. Martin and Kylie Mirmohamadi. Reading the garden: the settlement of Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008.

Instone, L. ‘Dancing with Dingoes: Humans, Animals, and the Australian Landscape.’ UTS Review 6.1(2000): 165-175.

—. ‘Fencing in/fencing and: Fences, sheep and other technologies of landscape production in Australia.’ Continuum 13.3 (1999): 371 – 381.

Jacobs, Jane M. Edge of Empire: Postcolonialism and the City. London: Routledge, 1996.

Keulartz, Josef, and Cor van der Weele. ‘Framing and reframing in invasion biology.’ Configurations 16 (2008): 93-115.

Kull, Christian, and Haripriya Rangan. ‘Acacia exchanges: Wattles, thorn trees, and the study of plant movements.’ Geoforum 39 (2008): 1258-1272.

Latour, Bruno. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences Into Democracy. (Tr. by Catherine Porter), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., USA, 2004.

—. We Have Never Been Modern. New York: Harvester/Wheatsheaf, 1993.

—. What is the style of matters of concern? Two lectures in empirical philosophy. Department of Philosophy of the University of Amsterdam. Van Gorcum: Amsterdam, 2008.

Lorimer, Jamie. ‘Living roofs and brownfield wildlife: towards a fluid biogeography of UK nature conservation.’ Environment and Planning A 40 (2008): 2042-2060.

Low, Tim. Feral Future. Ringwood, Vic: Viking, 1999.

—. The New Nature: Winners & Losers in Wild Australia. Melbourne: Viking, 2002.

Mawditt, Phillip. Personal communication, December 2009, Januray 2010.

McManus, P. ‘Mangrove battlelines: culture/nature and ecological restoration.’ Australian Geographer 37.1 (2006): 57-71.

Meserow, Hale. ‘Parks are for people.’ Australian Parks & Recreation May (1977): 11-13.

Morton, J., and N. Smith, N. ‘Planting Indigenous Species: A subversion of Australian eco-nationalism.’ Quicksands: Foundational Histories in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Ed. K. Neumann, N. Thomas, & H. Ericksen. Sydney: U of New South Wales P, 1999. 153-175.

Muecke, Stephen. ‘What the cassowary does not need to know.’ Australian Humanities Review 39-40 (2006).

Munro, Angela. ‘Melbourne’s Royal Park.’ Landscape Australia 4 (1998): 350-353

Plumwood, V. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. London: Routledge, 1993.

—. ‘The Cemetery Wars: Cemeteries, Biodiversity and the Sacred’ Local-Global: Identity, Security, Community, 3 (2007): 54-71.

Powell, R. H. ‘Australian native grasses for amenity purposes.’ Australian Parks August (1974): 25-27.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge, 1992.

Presland, G, Aboriginal Melbourne: The lost land of the Kulin people, Harriland Press, Forest Hill, Australia, 2001.

Ripley, C., Thün, G. and Velikov, K. ‘Matters of concern.’ Journal of Architectural Education (2009): 6-14.

Robbins, Paul. ‘Comparing invasive networks: cultural and political biogeographies of invasive species.’ The Geographical Review 94(2004): 139-56.

—. How Grasses, Weeds, and Chemicals Make Us Who We Are. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2007.

Rose, Deborah. B. Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2004.

Ross, James. Guide to best practice conservation of temperate native grasslands. World Wide Fund for Nature Australia, 1999.

Royal Park Protection Group (RPPG). ‘Royal Park again under threat by Premier Brumby’s major transport project plans.’ The Royal Park Protection Group Inc. News Bulletin Oct. 2009.

—. ‘Whatever happened to Royal Park?’ The Royal Park Protection Group Inc. News Bulletin July 2009.

Sexton, R. and Reilly, T. ‘Lungs of city smothered under concrete.’ The Age, 9 March 2008.

Stengers, Isabelle. The Invention of Modern Science. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2000.

Stuwe, John. ‘Native grasses as a management tool.’ Australian Parks and Recreation May (1981): 39-44.

The Editor, ‘Creating an urban forest.’ The Age, 5 Dec. 1984: 13.

The Weed Society of NSW. ‘Can Australian natives be weeds?’ The Weed Society of NSW News 2/3/2001. http://www.wsvic.org.au/w_news.php Accessed 14 Feb. 2010.

Trigger, D., J. Mulcock, A. Gaynor and Y. Toussaint. ‘Ecological restoration, cultural preferences and the symbolic politics of “nativeness” in Australia’. Geoforum, 39 (2008): 1273-1283.

Trigger, David. ‘Native vs. exotic: cultural discourses about flora, fauna and belonging in Australia.’ Sustainable planning and development, The sustainable World vol. 6. Ed. A. Kungolos, C. Brebbia, and E. Beriatos. Southampton: Wessex Institute of Technology Press, 2005.1301-10.

Tsing, Anna. ‘Unruly Edges: Mushrooms as Companion Species.’ Thinking with Donna Haraway. Ed. Sharon Ghamari-Tabrizi. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, forthcoming.

Urban Camp. ‘History of the camp.’ Urban Camp Melbourne. http://www.urbancamp.org.au/history.htm Accessed 23 Apr. 2010.

Van Dooren, Thom. ‘Vultures and their people in India: towards a biography of extinctions.’ Paper presented at ‘New’ Biogeographies: Invasive, Transgenic, and Hybrid Landscapes, Symposium, 15-17 February 2010, University of Wollongong.

Van Vuuren, Kitty. ‘The environment as an asset.’ Trust News February, 1991: 14-15, 17.

Verran, Helen. Science and an African logic. Chicago: U of Chigago P, 2001.

Warren, C. R. ‘Perspectives on the “alien” versus “native” species debate: a critique of concepts, language and practice.’ Progress in Human Geography 31 (2007): 427-446.

Whatmore, Sarah. Hybrid geographies: natures cultures spaces. London: Sage, 2002.

Whitehat. ‘The Whitehat Guide to Royal Park and Princes’ Park.’ http://www.whitehat.com.au/melbourne/Parks/RoyalPark.asp Accessed 23 Apr. 2010.

Whitehead, Georgina. ‘Parks and gardens.’ eMelbourne: the city past & present, 2008. http://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM01114b.htm Accessed 8 Dec. 2009

—. Civilising the city: a history of Melbourne’s public gardens. Melbourne: State Library of Victoria, 1997.

Williams, Kathryn and Cary, John. ‘Perception of native grassland in southeastern Australia.’ Ecological Management & Restoration 2.2 (2001): 139-144.

Williams, N. S. G., M. J. McDonnell, Emma J. Seager,. (2005). ‘Factors influencing the loss of an endangered ecosystem in an urbanising landscape: a case study of native grasslands from Melbourne, Australia.’ Landscape and Urban Planning 71: 35-49.

Zagorski, T., J.B. Kirkpatrick, and E. Stratford. ‘Gardens and the bush: gardeners’ attitudes towards urban trees and supporting urban tree programs.’ Environmental and Behaviour 39 (2004): 797-814.