By Melinda Hinkson

© all rights reserved. AHR is published in PDF and Print-on-Demand format by ANU E Press

In December 2008 Australia’s National Portrait Gallery opened to the public in a new building prominently positioned in the parliamentary triangle in the nation’s capital. In this essay I explore depictions of Aboriginality in the Gallery’s opening hang. The Gallery’s development since 19921 has coincided with a tumultuous period in relations between Indigenous and other Australians and a clash of interpretations over the past, present and future place of Aboriginal people in Australian society. Simultaneously over the same timeframe Aboriginal cultural production has continued to gain increasing recognition and prominence within the terms of fine art both nationally and internationally, and to be widely mobilised in support of a range of nationalist projects. The majority of non-Aboriginal Australians have little opportunity to interact with Aboriginal people and form their perceptions via media imagery that tends to deal in starkly negative or (less often) positive representations. What kind of visual experience of Aboriginality has been unveiled before the Australian public in this new cultural institution? Here I am interested to consider what kind of recognition the Gallery works with—does it include the work of Aboriginal cultural producers and subjects in support of a unified idea of the nation? Does it embrace difference procedurally, a kind of recognition identified by political philosopher Charles Taylor, that simultaneously denies the substantive claims associated with that difference? Or, does the Gallery have the capacity to foster recognition with transformative potential? Taking seriously the idea that interactions between visitors to the Gallery and the pictures they encounter will be influenced by the associations they bring with them, I interpret my own visits against a backdrop of a series of relevant events that unfolded in Canberra in February 2009.

I

On Monday 2 February I attend the High Court to hear the judgment in Wurridjal and others versus the Commonwealth of Australia and Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust, the challenge by traditional owners of the Aboriginal community of Maningrida in north Australia to the compulsory leasing of their lands, as part of the Northern Territory Intervention. The Intervention, which had been dramatically declared on 21 June 2007 by then Prime Minister John Howard, saw the deployment of armed forces personnel to help ‘stabilise’ remote Aboriginal communities, as well as a raft of measures introduced under the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act ostensibly as a response to reportage of widespread sexual abuse of children (Altman and Hinkson 2007). Coincidentally, the bringing down of the Court decision occurs on the first day of a ‘Convergence on Canberra’ by Aboriginal people from the Northern Territory to protest against continuation of the Intervention by the Rudd Labor government. They are here for the first sitting of Parliament for 2009, just weeks before the first anniversary of the Rudd government’s ‘Apology to the Stolen Generations’. Having learnt the High Court judgment is to be announced, they walk the few hundred metres from their camp at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy to be present. In Canberra as part of this contingent is my Warlpiri friend Napaljarri. She spots me as she enters the public gallery of the Court and rushes over. We embrace and then in characteristic Warlpiri style she sits down and proceeds to bring me up to date on ‘news’. Her niece’s son, she tells me, died before Christmas. He was twenty years old, a young man full of promise when I’d last seen him at his home town north-west of Alice Springs in central Australia.2 He had succumbed to some kind of cancerous tumour. Napaljarri is visibility distraught as she describes how she cared for this young man in his final days. After registering my shock, I ask after her daughter—just home, she tells me, after having been hospitalised in Adelaide following a heart attack. When I had last seen Napaljarri a year earlier she was grieving the loss of her youngest daughter who had died suddenly of heart related complications, also aged about twenty. In this short exchange I’m jolted back to a world far removed from Canberra. The importance of family, the ever-presence of death, invoked so straightforwardly as twin poles that structure daily life for Warlpiri people, provides a sobering backdrop to our anticipation of the High Court decision.

I try to process Napaljarri’s news as we sit side by side, taking in our unfamiliar surroundings, looking each other over for the first time in a year, waiting for the judges to enter the room and take their chairs. The public gallery of the court is by now nearly full—an audience composed largely of the Aboriginal visitors from the NT and those hosting their visit and providing support at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, a motley crew of the marginalised and radicalised, some sporting dreadlocks, torn clothes, bare feet, with a small number of suited advisers, legal types, media personnel, bureaucrats and academics interspersed across the benches. A court warden approaches a man seated in front of us and attempts to remove the plastic Aboriginal flag he is waving; then beats a hasty retreat on being warned ‘don’t touch it!’.

We are called on to ‘All Rise!’ (not all do), as the judges file in. Much of the room erupts in spontaneous laughter on the declaration ‘God Save the Queen!’. This is, I am reminded, a quite particular audience for a quite particular kind of performance of Australian law. And then proceedings quickly get underway. One by one each of the judges state their findings in a series of cases that have been heard in recent months. The talk is fast and difficult to grasp for a newcomer. ‘Hard language’ I murmur to Napaljarri, who keeps looking at me in expectation that I’d be able to translate the legalese.

The Wurridjal finding is 6-1 against the plaintiffs, with a direction that they pay the costs of the Commonwealth. But it is some time before the decision is translated by someone with an understanding of the language of this place, and then for it to sink in. Before this has occurred, the call comes again to ‘All Rise!’ as the Court adjourns and the judges and those in the public gallery file out.

Aboriginal people and their supporters mill just outside the front doors of the Court, trying to make sense of what has just happened. After a few minutes the reality (if not the full comprehension) of the Court’s decision sinks in, and a demonstration is hurriedly formed behind a megaphone chanting ‘Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land!’, and this newly animated social body re-enters the Court and occupies the foyer. Within minutes the group is surrounded by federal police, and, after a skirmish, encouraged to disband and leave the building. One man is taken into custody but later released without charge. Senior Aboriginal men from the Northern Territory stand visibly distant from this protest, outside the Court looking on in muted discomfort as the action unfolds. For such seasoned land rights warriors, this is not their style of protest.

II

Flashes of these experiences keep me awake that night and are at the forefront of my mind as I enter the National Portrait Gallery the following morning, specifically to explore how depictions of Aboriginality feature as a dimension of the new visual experience recently unveiled before the Australian public. The Gallery finally acquired status as a fully-fledged national cultural institution with the completion and opening of its new building in December 2008. Positioned in the parliamentary triangle, sited next to the High Court and within a few hundred metres of the National Library of Australia, National Gallery of Australia and the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, it now makes claim to a prominent and distinctive role in reflecting what it means to be Australian back to its visitors.

The opening of a new national cultural institution in Australia is a relatively rare event. What is this new gallery? Part of its interest and potential surely lies in its very ambiguity: this is not simply another fine art gallery, nor a museum in the conventional sense of the term. The Gallery is concerned specifically with ‘portraits of subjects who have made a major impact on Australia’ (National Portrait Gallery). For this reason the very idea of a portrait gallery built around the recognition of ‘notable’ individuals and their contribution to nation making has been scorned by some as an exercise in barren elitism, and the gallery’s ambiguous status accused of giving rise to nothing more than a mix of ‘bad history and inadequate psychology with inferior art’ (McQueen). Yet such criticism seems to miss a fundamental point: this is a Gallery born in an era of accelerated technological mediation. Part of the aim of the Gallery requires it to eschew the values of high art in favour of forms of image-making drawn from a wider public domain. This is a place where the story of the nation is to be amplified through the story of individual experience and imagination. The genre of portraiture and presumably the Gallery itself appeals to a broader audience than other forms of art precisely because it looks through the lens of individual experience (note the 300,000 visitors to the Gallery in the first three months of its opening). Portraiture has been crucial to the formation and articulation of modern individualism (Woodall); it might be seen as a primary genre through which the culture of western modernity is animated and reinforced. In a society that measures social achievement in large part through a person’s attainment of status as image, most often attended to in the form of the face, a portrait gallery is likely to have a particular appeal, especially for its direct engagement with the cult of celebrity, with forms of image culture that are embraced in the world beyond art galleries.3 And while I will show that chronology and individualism provide the underlying structures that organise the viewing experience here, it will be seen that they by no means imply an interpretive straightjacket.

The Gallery’s stated aim is strongly educational: ‘to increase the understanding of the Australian people—their identity, history, creativity and culture—through portraiture’. Yet it is possible to read much potential latitude into such a seemingly straightforward didactic statement. Because its business is images, representations, the Gallery must avoid the classical museological practice of attempting to tether objects too closely to particular classificatory interpretations (whether these be scientific or art historical). As in any gallery, the images themselves must be allowed to appeal to the viewer for the many ways they might fire the imagination. The Gallery’s founding director, Andrew Sayers,4 suggested the Gallery be approached as ‘an idea’, emphasising the work of imagination involved in any artistic endeavour to render the complex lineaments of identity into visible form. It may well be that the very looseness of ‘idea’ can work to paper over a lack of coherence or clear organising principle, but if we approach this gallery as a product of the cultural environment with which it simultaneously engages, we arrive, I shall argue, at a somewhat different assessment.

Demand for recognition of Aboriginal people’s distinctive status as first inhabitants of this country characterises a core dynamic of Australian national politics. But as political philosopher Charles Taylor has argued, there is a tendency in modern liberal societies to perform certain kinds of recognition that ultimately result in substantive difference being dissolved in the name of national unity (Taylor; Povinelli; Hage; Lattas; Everrett). In this sense democracy and its privileging of the rights and freedoms of the individual citizen has particular and insidious implications for the cultural forms of colonised peoples, as well as for marginal migrant groups within multicultural societies. Taylor cites the acceptance of other societies’ traditions of visual culture within the terms of our own canon of ‘art’ and ‘artist’ as an example of the kind of recognition that ultimately reduces the different to the homogenised preferences of the nation-state and commodity market (see Merlan; Dibley). We can rejoice in the wonder of Aboriginal art and its enrichment of the nation while disparaging or rejecting the ways of life that sustain those very forms of cultural production. Is this the mode of recognition that the Gallery performs, or does it have the capacity to foster a transformative kind of recognition that Taylor invokes from philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer, in which a ‘fusion of horizons’ might be born of our willingness to open our existing frames of value to other ways of seeing, to a genuine, and potentially transformative, interaction with those of the other? Can the Gallery be a place where visitors might change the way they understand Australia and Aboriginal people’s place within it? Can it crack open our assumptions about the relationship between an individual and society? The paradigm of recognition has been dismissed by some as lacking the kind of transformative potential we find in dialogical encounters. Yet the situation considered here is one in which the presence of the other, self-other dialogue, is not achievable. Instead the other is only graspable here through pictures, representations. In such contexts the question of the limits and potentiality of recognition seems usefully to reassert itself.

This essay is an experiment in making visible the conjunction between what we observe as processes of public culture and policy making occurring at the level of the everyday, and analytic reflection on a particular set of visual experiences. As I was exploring the opening hang of the Gallery in February 2009, a series of unrelated events unfolded in Australia that both drew attention to and called forth aspects of public imagination that seemed to bear directly on issues I was grappling with. The High Court decision in Wurridjal reflected upon above came hard on the heels of a series of contradictory messages conveyed in federal government statements on Indigenous affairs: the first anniversary of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s historic Apology in the federal parliament to the Stolen Generations on the one hand, firm insistence on retaining the controversial Northern Territory Intervention on the other. The shaping of nationalist sentiment that occurred in and through these events came to constitute something of a backdrop against which my analysis developed. My proposition is that such an interpretive model is entirely apposite for making sense of the Gallery for two reasons. Firstly, because it mirrors the process viewers enter into when they interact with any picture—they draw upon a conjunction of personal experience and abstract knowledge in order to produce meaning and form judgments (Elkins; Clark); and secondly, because the Gallery’s charter places it at the centre of a creative collision between fine art and wider understandings of social value. In a society where recognition is principally achieved in media images, there is a recursive loop between the Gallery and its visitors who bring with them expectations and desires increasingly fostered and produced through this same mediatised process. Is it possible to simultaneously sustain and fracture that loop?

III

The first picture encountered on entering the most centrally located contemporary gallery is Gordon Bennett’s portrait Eddie Mabo, 1996; highly symbolic given my experience of the preceding day, and a powerful reminder of the high-water mark of the High Court’s 1992 decision, giving legal and moral force to the recognition of Aboriginal claims. Bennett’s image of Eddie Mabo’s joyous face is taken from a newspaper, overlaid partly with a faint dotted stipple indexical of central Australian acrylic ‘dot’ painting, and surrounded by layered grabs of text. The partial words that frame Mabo’s head are taken from newspaper headlines, a multi-layered jumble conjuring the toxic environment of race relations and the complex discursive field of conflict that erupted as his claim to ownership of his customary lands in the Torres Strait was interpreted in law and subsequently legislatively enshrined in the Native Title Act. Simultaneously, a transformative set of events and an ongoing unresolved tension at the heart of Australian identity are galvanised in this picture.

Rather than portraying Mabo the man heroically, Bennett’s picture is a powerful statement about the nature of our mediated public culture and the processes through which we grasp and indeed produce images of persons, the events with which they are associated and the ideas they come to stand for in the present. As Bennett reflects in his statement about the work, Mabo himself is only knowable to us through the images and discourses that make him present in the public domain.5 Here there is no attempt to depict physical likeness, or to get at qualities that might be associated with ‘Eddie Mabo the man’. Bennett’s work points in another direction. It conveys a sense of the myth making we, the nation, undertake when we turn a person and his achievements into an element of public imagination. In looking at Mabo we see our collective moral redemption—redemption echoed in our regard for ‘authentic’ Aboriginal art, as we are reminded by the faint stipple of dots that intrudes on our view of Mabo’s face. But simultaneously with this redemption Bennett conjures up the conflicting narratives of national self-understanding that have been, and continue to be, hotly contested in Australia in the ensuing ‘culture wars’ (Windschuttle; Manne). In short, in producing Mabo we produce ourselves.

Hanging beside Mabo is Ross Hannaford’s 2006 portrait of Lowitja O’Donoghue, first chairperson of the now disbanded national Indigenous representative body, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, tireless campaigner for Aboriginal rights, former Australian of the Year, a once-touted possible Governor-General of Australia, a formidable woman known for her straight talking, uncompromising principles. It is a painting of compelling likeness, and conveys well a complex sentiment; one feels drawn to the picture but simultaneously held at reserved distance by the subject’s regal disposition. At the opening of the Gallery in December 2008 O’Donoghue took aside celebrity portrait painter and Australian icon Rolf Harris for a ‘quiet word’ about recent comments he had made in the media suggesting Aboriginal people should ‘get up off their arses’ and clean up their communities. At the conclusion of the forty-minute discussion a suitably chastened Harris was quick to issue a public apology (Edwards). He lingered in front of O’Donoghue’s portrait for newspaper photographers.

Recalling this episode in the gallery space, it seems to ricochet off Bennett’s Mabo; confirming the artist’s analysis, echoing a sense of the circular processes through which stereotypes are produced. Harris’ directive: ‘get up off their arses’ endorses, reproduces and fuels a conventionalised view of Aboriginal styles of life that he freely admits to having taken from the mainstream mediascape. The media reportage of Harris’ exchange with O’Donoghue in the Gallery in the context of its opening might from one perspective be interpreted as a kind of performative gift to the new cultural institution—these two noteworthy Australians have enacted in the flesh exactly the kind of horizon-shifting encounter this Gallery might hope to facilitate: disrupting stereotypes; confounding an imagined stark separation between the abstracted spaces of media and those of the intimate face-to-face; fostering a clear sense that coming to know the other is a relational and potentially transformative exercise.

The third large portrait that completes this wall is Matthÿs Gerber’s lurid 2002 work, George Tjungarrayi. This lush abstract image in a wash of purple, green, blue and orange only settles into the recognisable dimensions of a face once the viewer forces that form upon it. Meditating on the creative tension between portraiture and abstraction, Gerber’s work celebrates his Western Desert subject’s own contribution as an abstract painter in his own right, but gives no access to the physicality of the person, nor his own painterly aesthetic, nor the ‘natural’ environment in which we might expect to see him pictured.

Taken together these three images make a powerful statement about the kind of visual experience the Gallery intends to foster. At the most obvious level is a statement about the central place of Aboriginal experience, perspective and achievement in moulding ‘Australia’ as we know it today. For the majority of Australians who have no interaction with Aboriginal persons in the course of their daily lives, here is an opportunity for a particular kind of mediated intimacy with their images. Three acclaimed individuals—an abstract painter of relationships of people to country, a political leader and activist, and a subversive whose image came to stand for the recognition of Aboriginal land title and Australia’s moral redemption from its colonial origins, convey a sense of the breadth of such contributions. This might be interpreted as the incorporative aspect of the Gallery’s recognition (ie at its simplest: Aborigines have contributed to the building of the nation). But beyond this, these works present a challenging and complex set of statements about the nature of portraiture and more broadly about representation itself. The diversity of depictions simultaneously reassure and provoke viewers as to the range of portraits they will encounter. If visitors were under any misapprehension, Mabo makes this abundantly clear: an image is not a person, nor is it necessarily indexical of a person in a straightforward way. These works challenge viewers to consider the relationship between a person and his or her image. And of particular interest to the concerns of this essay is a sense in which all three paintings explore what might be described as the limits of recognition in relations between Aboriginal and other Australians.

In the terms established by the Gallery, as stated clearly on text panels, the images to behold here are ‘encounters’: between artist and subject, between viewer and picture, between Indigenous and other Australians. More than simply offering a new place to celebrate Australian heroes of modern individualism, in subtle ways the Gallery provokes visitors to think about the relational processes in which both art and identity are created. Its displays challenge the vision of a unified nation, particularly those ways of imagining ‘Australia’ that would disentangle Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal experience from their interpenetration, or conversely imagine the dissolution of their difference. On the face of it this may appear an unsurprising narrative strategy for a new national cultural institution to pursue.6 While the themes of ‘encounter’ and ‘relatedness’ may have become ubiquitous in new museums (Message), and to establish a form of recognition that takes the sting out of the visceral, violent, repressive relations that lie at the very foundations of settler-colonial nations in favour of more gentle, celebratory and blood-less readings of nation making, it will be seen that something more complex is achieved here.

IV

A distinctive characteristic of the way the Gallery structures viewing experience is in the interplay between an artwork and its text panel. Unlike a conventional fine art gallery, here we find text panels of 150-200 words of carefully crafted text, often conveying more information about subjects than artists. These panels are fundamental to the Gallery’s stated educational aim, and may play a role in attracting a wider pool of visitors than tend to be drawn to conventional fine art galleries (I’m reminded of the extensive survey of visitors to European galleries conducted by Bourdieu and Darbel that found that 89% of respondents identifying as ‘working class’ stated they would like artworks to be accompanied by explanatory panels). In this Gallery it is common to find viewers dedicating as much if not more time to reading text as looking at pictures. The exhibition experience, suggests the Gallery’s senior curator, is intended to be ‘a good read’.7

One of the interesting things about looking at portraits of an earlier era in conjunction with text panels is that temporal experience is complicated in particular ways. This is strikingly the case with Aboriginal portraits of the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, where a clear gulf exists between events described in the text and the pictures before one’s eyes. Tasmanian Trucanini is depicted here by Duterrau (c. 1835) as unblemished, proud, attired in ceremonial regalia, in a stance of radiant, confident nobility. Her head and torso takes up much of the canvas, the only contextual backdrop an eerily coloured sky, evoking twilight, as if in the moment before history overran Trucanini and her community: ‘Trukanini saw many of her family members and close associates killed by white people’ states the text panel bluntly. The picture radiates one set of associations, the text another; the viewer’s own perspective ultimately organises the conjunction between the two. The first two historical galleries, laid out chronologically, have a deeply melancholy aura deriving from our knowing what became of these persons and the communities to which they belonged after their portraits were made. Yet these first rooms also disrupt any expectation that the visual journey here will be simply celebratory of Australia’s origins in European settlement. While large portraits of James Cook and Joseph Banks establish the gallery’s origin point for thinking about ‘Australia’, in this distinctively post-Mabo hang, pictures of colonisers and colonised share the same space, eye-balling each other across the room, as in the pairing of Duterrau’s pictures of Trucanini and George Robinson, architect of the notorious civilising experiment that saw hundreds of Tasmanian Aboriginal people transported to Flinders Island, where most died soon after. These works were all created by non-Aboriginal artists; nevertheless they animate complex trajectories, their subjects defying each other’s versions of nation making.

Here lies the first important way in which the gallery’s carefully structured chronological narrative is disrupted in the experience of viewing. We encounter these colonial pictures in the cultural time-space of the present. The Port Jackson Painter’s delicate picture, Bennelong, conveys an imagined pre-colonial innocence starkly at odds with what we know of his eventual demise. Augustus Earle’s Bungaree is a masterly study of the contradictory experience that characterised life in the colony for Aboriginal mediators of the nineteenth century. Thomas Bock’s 1842 portrait of Tasmanian Aboriginal girl Mathinna takes on a new significance and set of associations when we know it inspired Aboriginal dance company Bangarra to produce a performance by the same name. Similarly we might read Mathinna’s tragic biography not just through the gallery text panel, but through the widely publicised narratives of those Aboriginal people we have come to recognise as members of the Stolen Generations, and in the culture wars that contest such recognition; through the symbolic discourse of the federal government’s recent Apology to those people; and again through Richard Flanagan’s fictionalised account of Mathinna’s story in his 2007 novel Wanting. Pictures become mired in the complex associations and forms of imagining we bring to bear upon them. We cannot enter into the time of their making. Rather, we encounter them within ours.

VI

Just as a National Portrait Gallery is primarily concerned with national identity, ultimately it assumes a particular kind of subject to animate that identity: the individual achiever, the self-made modern subject. Throughout the Gallery are many instances of Aboriginal individuals being included in this story of nation building through individual pursuit: as great artists, actors, poets, musicians, sportsmen and women, bureaucrats, politicians. Against this apparently seamless flow of nation making come moments where we are reminded that race has and continues to be a primary point of agitation in national identity—in St Kilda football player Nicky Winmar’s defiant lifting of his football jumper to bare his black skin; in then Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s pouring earth into the hand of Gurindji man Vincent Lingiari as he is granted ownership of his land; Charles Perkins absorbed in thought riding on a train evoking the ‘Freedom Rides’; and, looking back further, Barak’s campaign for his community to live in relative autonomy at Coranderrk in Victoria. Pictures by Tommy McCrae subtly invoke a highly charged way of seeing ceremonial action in a place and time when such ceremony was under attack by white authorities; while William Dargie’s portrait of Albert Namatjira is a lightning rod for thinking about the collision of two cultural orders and what many find an impossible challenge of navigating between them.

The inclusion of these pictures and the symbolic moments they stand for in a chronological narrative of individual achievement is significant—here the story of nation making is conveyed not in terms of discrete or parallel black and white histories, not simply as an incorporative process, but a chronological narrative inflected with recognition of its multiple, contradictory, and often devastating implications for Aboriginal people.

But can the Gallery go beyond this? What scope is there to unsettle the metanarrative of individualised subjectivity that the very idea of a portrait gallery rests upon? Can different ways of being Australian, different modes of personhood be conveyed here that challenge claims to the universality of individualism? Can Taylor’s idea of a possible ‘fusion of horizons’ be explored here or does the very idea of a portrait gallery preclude us from recognising ontologically different ways of conceiving relations between persons and their forms of visual culture, and beyond this the possibility of relating empathetically across such divides?

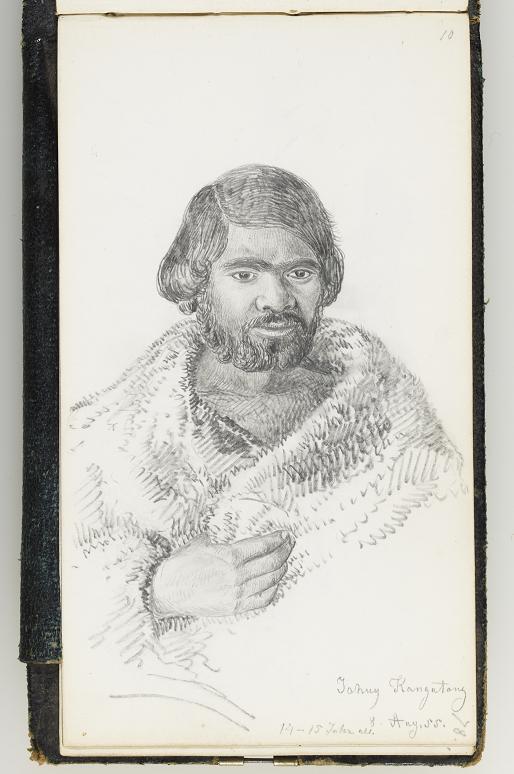

“Johny the Artiste Kongatong – 8 Aug 55 (Aborigine).”

Pencil drawing by Eugene von Guerard in his Sketchbook XXIV, No. 6: Australia. 3 Jul. – Aug., Dec. 1855. (Ref: DGB 16/v. 3/f.77)

Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales. Reproduced by permission.

One particular visual enactment of ‘encounter’ arguably takes us some distance in this direction. In the room dealing with portraits of the second half of the nineteenth century, two small drawings are mounted side by side in a display case: Eugene von Guérard’s ‘sketch of Johnny the artist, Kangatong’ and ‘Eugene von Guérard sketching’, by an artist identified as ‘Black Johnny’. These two sketches were made in the winter of 1855 during the month von Guérard spent at Kangatong near Warrnambool. Von Guérard’s sketch of the teenaged stock keeper is a clear, confident pencil drawing of the features of a handsome male face, executed with the finesse of an artist at the height of his powers. Johnny’s sketch of the painter is made in coloured pencil; it is the work of a gifted novice. It depicts the whole physical person, his dress, the detail of his hat, and captures well von Guérard’s bodily disposition as he sits at work on a chair, legs crossed, drawing tool in one hand, paper in the other.

Portrait of von Guerard sketching, 1855.

Portrait of von Guerard sketching, 1855.

Coloured pencil drawing by Black Johnny, inscribed in ink: “Mein Portrait / v[on] / dem Eingeborenen—Black Johnny Kangatong August. 1855”. (Ref: PXA 606/f.3)

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Reproduced by permission.

Johnny’s sketch of the artist puts me in mind of a series of wax crayon drawings made by Warlpiri people at Hooker Creek in the Northern Territory in the early 1950s for anthropologist Mervyn Meggitt. The drawings were produced as part of the tutelage the anthropologist and his informants were engaged in, primarily dealing with ceremonial themes. A small number of drawings explored vernacular topics, some revealing Warlpiri perspectives on European styles of life. In one of the most memorable of these pictures Larry Jungarrayi Spencer draws the superintendent’s house as a block of black flyscreen hovering above the earth, a deep blue sky separating its foundations from the yellow Spinifex ground. Here Spencer evokes a widespread sensibility among Warlpiri people of his generation that a notable difference between themselves and Europeans is that the latter lived above, not on, the ground (Hinkson ‘Warlpiri drawings’). Johnny seems to give a similar significance to the technology that mediates the European artist’s experience of the landscape—his chair, his drawing materials, his dress. Von Guérard meanwhile works in the tradition of life drawing, focusing his attention on the precise depiction of his subject’s head. In both cases drawing is a creative medium of sense making, it contributes a vital dimension to a wider conversation between persons attempting to grasp each other’s view of the world.

Andrew Sayers has observed that a very particular kind of encounter is exercised in Johnny and von Guérard’s drawings, not one that can be made to stand for a generalised interaction between Aborigines and Europeans of the era (Sayers, Aboriginal Artists 2). The meeting of these two artists was not accidental; they came together on the property of wealthy squatter James Dawson who had a reputation for genuine interest in and empathy for Aboriginal people and their customary practices. Johnny acquired from Dawson his European name and employment as a stock keeper. Dawson in turn invited von Guérard, by now a renowned artist, to his property to paint. Positioned side by side here for the first time, these sketches provoke simply, but powerfully, a sense of picture-making as a dialogical process of coming to grips with another from a distinctive perspective.

Sharing the display case with these drawings is Fred Kruger’s ‘Souvenir album of Victorian Aboriginals, kings, queens, etc’ c. 1877. Here are four individual portraits—the first two of bare-chested ‘kings’, while a third ‘King William—Mt Cole’ and fourth ‘Queen Mary—Ballarat’ are ceremonially attired and piled high with arms full of paraphernalia, possum skins, boomerangs. Kruger’s pictures are powerful indications of the role of image-making in the politicking of nation-state dealings with Aboriginal persons.8 These photographs reveal one conventionalised approach to picturing Aboriginal subjects in this period, as Aborigines were caught between the impossible poles of how we imagined their pre-colonial existence on the one hand and their successful assimilation on the other. Yet Johnny and von Guérard’s pictures make clear this was by no means the only possible framework for representational engagement, nor its only outcome. Something disruptively productive is achieved by placing Kruger’s pictures alongside the sketches by Johnny and von Guérard. As a suite, these pictures draw attention to the radically different possibilities of representation as a medium of encounter, as othering or intersubjective, as projection or negotiation, as inclusionary or transformative.

VII

Wednesday 4 February: It is perhaps unsurprising that I’m feeling drawn to think about how Aboriginality is conveyed in the Gallery just as the federal government reasserts its commitment to the Northern Territory Intervention, with its ‘normalising’ and individualising measures (see Altman and Hinkson, ‘Very risky business’). After work I drive to the Tent Embassy to pick up Napaljarri and bring her home for dinner. The Warlpiri people who have travelled to Canberra are resting in a tarpaulin-shaded area. A number of their painted canvases are laid out on the grass nearby on display for prospective purchasers. These have been brought along to help generate ‘pocket money’ for the trip.9 It has been a stinking hot day and there is a disconsolate mood among the group. They tell me they are upset at the response they received earlier in the day in their meeting at Parliament House with the Minister for Indigenous Affairs. A meeting scheduled for thirty minutes was reduced to just fifteen, the Minister apologising she had ‘orders to sign’. She was said to have spent much of their short time together ‘tippin’ elbow’—looking at her watch.

These residents of one township have been highly outspoken critics of the NT Intervention. Yet the strength of their case has been fractured by the countervailing voice of an ex-resident Warlpiri woman, whose public pronouncements contradict an otherwise largely unified public position. In her forays into the media this woman suggests domestic violence is widespread in the town and pleads for the Intervention to continue. On visiting the town in October 2008 to open a new swimming pool, the Minister was handed a petition signed by more than 200 residents that described the government’s decision to continue with the Intervention as an insult. But reportage of the pool opening event provoked local unrest when one prominent senior woman was quoted as saying the government’s income quarantining was ‘working’, in direct contradiction of the claims of the petition. The woman in question subsequently issued a statement describing the reportage of her comments as ‘lies’ and denouncing the Intervention as ‘rubbish’. She had travelled to Canberra with the group ostensibly seeking an apology from the Minister. Just days earlier, at the conclusion of a government sponsored workshop on domestic violence, the Minister had posed for assembled media alongside the ex-resident Warlpiri woman. This pro-Intervention campaigner has subsequently been made chair of a new advisory group for the NT government.

Perhaps ironically, for these people for whom English is spoken as a second, third or fourth language, the articulation of opposing views on government policy from within the same locality continues to be played out in globalised media space: projected outwards from central Australia, snippets of commentary spoken to journalists find their way into diverse media outlets, in one recent case no less prominent than the Wall Street Journal (Trofimov), before being electronically bounced back to central Australia to further agitate debate and division. But the full complexity of the local-global nexus in this particular case is revealed by Napaljarri who over dinner describes to me the ways in which Warlpiri contestation over the Intervention now maps onto the turbulent local politics of retribution following the suspicious death of a young man. Here I am reminded with profound clarity that while Warlpiri regularly participate in regional, national and international events, and strive to assert their rights as Australian citizens in political contests with governments, they continue to invoke clear (albeit at times contradictory) lines between the moral and rational coordinates of their lifeworld, expressed as Yapa (Warlpiri) way, and those of Kardiya (white people, wider Australia).

VIII

The most compelling sense of the Gallery’s potential as a place that will deal creatively with both questions of identity and its definition of portraiture is to be found in the opening special exhibition Open Air: Portraits in the Landscape.10 The first ‘work’ encountered here is a set of Tiwi Pukumani Poles, paint faded and peeling, wood half-rotten, detritus falling at their base. If this cultural production is taken to be a portrait then it stands for a more complex and multi-levelled set of associations than tends to be grasped in the notion of individual achievement. These funeral poles manifest relations between the living and dead, between a lineage of kin associated with a particular place through a body of ancestral knowledge and that of a deceased person. Baldwin Spencer’s compelling photograph of an unnamed Tiwi man crouching among a set of poles deep in a north Australian tropical forest hangs nearby. It humanises the poles for an unknowing audience and conveys something of this different way of enlivening the world through visual cultural production.

The distinctive basis of forms of Aboriginal identity and the visual expressions to which these give rise are core themes of this special installation. Here we find what are essentially portraits of the creation of the world in all of its physical, social and moral dimensions. Art becomes seen here most clearly, in the words of Howard Morphy (2), as ‘a form of action in the world’. The flair of individual producers is to be appreciated in the context of collectively held visual languages through which the world is conjured and depicted. This double distinction is strongly elaborated through the bark paintings produced by members of the Marika family and in the collaborative canvases of brothers Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri.

The works selected for this exhibition emphasise that the contemporary coordinates of Aboriginal identity are by no means isolated from the time-space of mainstream Australia. There is a clear sense here of art as a thoroughly contemporary and intercultural production: in Marika’s Sydney; in the Wik sculptures of Cape York that incorporate new carpentry techniques; and in a series of works that deal in various ways with Aboriginal people’s relationships to land in the wake of dispossession, most poignantly Ricky Maynard’s prison series and Darren Siwes’ meditation on contemporary alienation.

Aside from confronting head-on the complexity of Aboriginal identity in post-colonial Australia, works in this exhibition convey ideas that seem central to the question of whether the gallery might have the capacity to transcend Taylor’s ‘procedural’ recognition in pursuit of a ‘fusion of horizons’. The first of these concerns the recognition of the very ontological basis of different visual culture systems, the idea that there might be different ways of conceiving persons and their portraits. The second attends to the ultimate limits of what might be knowable across these systems.

One of the most affecting paintings to my eyes is Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri’s Trial By Fire. This large and highly-charged painting makes an imposing presence. It takes some of its force from our knowledge of the context of its creation. As has been described vividly by Geoffrey Bardon, the school teacher who was centrally involved in the establishment of Papunya painting movement, Papunya was a place of devastating sickness, distress and death for the Aboriginal people who came to live there either willingly or by force from the late 1950s, in the midst of a prolonged drought and a governmental push to centralise and make sedentary nomadic desert Aborigines. The indifference and disdain shown to these people by many of the white officials charged with running the settlement, and the melancholy despair that flourished as a result of the stifling of their deeply-held cultural imperatives, produced the demoralising features of this new outback ghetto. The first wave of visual production by senior men under Bardon’s encouragement resulted in pictures of astonishing power and radiance—a torrent of built up creative energy poured forth onto plywood, particle board, scraps of old wood and any other material the men could get their hands on. In the period in which these first works were produced the painters were isolated from their customary lands, having no transport of their own and, as wards of the state, being restricted in their movement by government regulations. Their painting was an inexhaustible process of invoking the cosmological world that bound them to their distant country. In Bardon’s words, painting allowed them to become ‘free men in an otherwise brutal and degrading environment’ (24).

Trial by Fire was produced a few years after this initial outpouring of creativity, and after the painting men had in certain respects secularised their aesthetic, following accusations by their neighbouring ritual partners that the paintings were revealing more ‘inside’ knowledge to the outside world than was acceptable. But Leura’s work retains a clear sense of the vital energy of the earliest paintings, its charged ceremonial context shimmers in the haunting smoky shadows that make present the bodies of two figures running over a dotted ground of sacred sites. This is the kind of visual narrative to which anthropologist WEH Stanner might have been referring when he spoke of there being dimensions of the beauty and mystery of Aboriginal religious thought and expression that ‘lay, and properly so, beyond the reach of anthropology’ (Sutton). Trial by Fire is a work of great power, and part of that power derives from the sense that it deals with organising principles that lie beyond our comprehension, ideas and ways of seeing the world and people’s place within it that might be apparent to us but ultimately ungraspable outside of that system.

One other body of work in Open Air seems particularly to manifest both the possibilities and limits of portraiture as a vehicle for a kind of recognition that transcends the procedural: the paintings by Tim Johnson. Here the artist has produced what are essentially visual diaries of his visits to Papunya in the early 1980s. Most compellingly he reveals the inner workings of his own head, a sense of the process he is engaged in as he attempts to come to terms with an utterly different way of ordering the world (see also Sayers, Open Air 24). Works call attention to different elements of this experience. One portrait of Daisy and Tim Leura depicts their camp, and the searing central Australian light through which the artist glimpses the scene, but only faintly recalls the artists’ faces. Here and in other pictures Johnson is more preoccupied with the detail of the painters’ work than the fine detail of their physical form. What we seem to be presented with here, again, is an idea of painting as a meeting point between persons trying to grasp each other’s worlds.

The work from this series that holds my attention longest is Johnson’s 2002 portrait Clifford Possum Tjapaltarri. Here sits Possum, his face and physical form clearly rendered, meditating contentedly, Buddha-like, clothed in white, surrounded by an ether filled with elements—persons, animals, flora, camp scenes, artists at work, boomerangs and spears, the Rainbow Serpent. Johnson attempts to assemble the various dimensions of a person around his physical likeness, to call forth the ontological ground of the subject who floats, as yet unanchored in the artist’s mind, or rather and more particularly against a sea of dotted and brushed paint. No element is privileged over another; it is as if Johnson is aware he is yet to acquire the language, the worldview, through which they might be ordered. It is through the language of paint and Buddhism that he reveals himself visually grasping and rendering Possum.

Morphy has drawn attention to a similar reflexive process at work in Mawalan Marika’s portrait Djan’kawu, also included in this exhibition, which in one panel depicts the artist reflecting upon himself and his acts of ceremonial production (16). Both artists seem to be engaged in painting as self-reflexive sense-making activity. But it is in Johnson’s painting that something important is enacted before the eyes of the viewer about the potential and the constraints of representational systems as mediums of cross-cultural encounter. Johnson conveys well the heady experience of being immersed in a world one is yet to understand, the mesmerising excitement, the awareness that so much of interest lies outside of one’s grasp. He reveals the lenses through which he attempts to know the Other and his awareness of the limits of his knowledge. In a number of works he puts his paint beside that of some of the Papunya painters, perhaps reaching for a kind of fusion of horizons upon the same canvas? I’m not convinced that these works are successful in that venture. But perhaps part of the ultimate message in Johnson’s work is about the immense difficulty of that very process?

Like Bennett’s Mabo, Johnson’s pictures point away from their subjects in a number of important respects. They meditate on the apparently unbreachable ontological gulf between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal experience. Johnson renders the partiality of his comprehension of the universe he briefly enters at Papunya in the manner of an unfinished work, a grasping that will always and necessarily be partial. His painting Don Tjungarrayi conveys this sensibility most clearly, a seemingly unfinished painting of a subject at work on an unfinished canvas, both acts still in a process of becoming.

IX

Johnson enacts something that agitates at the centre of current debates over what kind of future Aboriginal people in remote Australia might aspire to, and the nation’s ongoing failure to empathetically respond to the difference that lies at the core of such aspirations; a crucial question for those people, for the nation, and for this new Gallery that seeks creatively to respond to its multiple, contradictory and contested desires. Will we foster a vision for the future for these people that is constrained by our still dominant (but increasingly precarious-looking) market-driven individualist aspirations? Will we treat them simply as citizens? Or, will we support Aboriginal people vesting hope in other kinds of value and forms of relatedness, including ways of seeing the world and humanity that seem to directly run against those privileged by the dominant society?11

Following its election to office in late 2007 the new Rudd government was quick to act on a promise to offer a formal apology to the Aboriginal Stolen Generations. The potential transcendentalism of this event was powerfully evoked in the Prime Minister’s speech:

Let us seize the day … let it not become a moment of mere sentimental reflection. Let us take it with both hands and allow this day, this day of national reconciliation to become one of those rare moments in which we might just be able to transform the way in which the nation thinks about itself. (Rudd)

Twelve months later this rhetoric had fallen flat, the galvanised focus and promised energy dissipated. With some limited exceptions, Aboriginal affairs seemed, especially when viewed from Warlpiri country, to be conducted in a manner broadly continuous with that of the previous government. As certain intervention measures took hold, combined with the dissolution of community governance structures (following their replacement with new regional shires) and the disbanding of bi-lingual education programs, demoralisation was setting in. The Apology increasingly appeared to be a cunning act of procedural recognition (Povinelli; Kowal).

A year after the Apology, Reconciliation Australia published their first ‘Barometer’, a survey comparing attitudes of Indigenous and other Australians to each other. The striking finding of this survey fixed upon by media outlets was that the overwhelming majority of Indigenous and other Australians do not trust each other. If trust is principally established in face-to-face interactions (Giddens) then this finding is unsurprising—the majority of non-Aboriginal Australians have little opportunity to interact with Aboriginal persons in the course of ordinary daily life (see Hinkson ‘Media images’). They take their impressions from the mediated encounters offered by television, newspaper reportage and other sources of public imaginary. The opening hang of the National Portrait Gallery offers a significant new avenue for differently-inflected mediated encounters, an encounter where pictures of persons and ways of seeing the world complexify the stark images of undifferentiated otherness that so often circulate in other arenas.

Perhaps most significantly, the opening displays gently urge visitors to see depictions of Aboriginality in the relational terms of their production, as part of a shared past-present in which the trajectories of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australia may seem at odds, yet also deeply entangled. However, Open Air with its great diversity of ways of reflecting on the place of Aboriginal people in Australian society is a temporary display. As this essay is finalised prior to going to press, the director who oversaw the opening program has now left the Gallery to head up the National Museum of Australia. To what extent similar ideas might be carried through in the next stage of the Gallery’s life is yet to be seen.

* * *

I didn’t take Napaljarri to the Gallery during her short stay in Canberra; she was occupied with more pressing business. But I would have been interested in her response. A painter herself, a passionate defender of Warlpiri people’s aspiration to continue living close to their customary lands and to pursue a life that differs in many ways from mainstream Australia, Napaljarri is also an enthusiastic traveller, video maker, broadcaster and observer of global popular culture. I will never forget her confronting me in Alice Springs one day in 1997, distressed and in tears on having just learned of the death of Princess Diana. ‘I idolised that woman!’, she cried as her adult son and I exchanged bewildered looks. Napaljarri has grown up with a fusion of horizons. But when I discussed this essay with her, she brought my attention back to the other side of the viewing encounter. Did I know of photographs of her mother and father that might be hanging in ‘the gallery’ in Canberra, she asked? It was only on later reflection that I recalled, with deep embarrassment, that Napaljarri had raised the issue of these photographs in conversation with me some fifteen years ago, when our discussion would have been fixed on other matters. And I had not followed up on my promise to try and locate them for her.

This essay has explored what kind of engagement might be possible with an Other when the only medium available for interaction is images, portraits. Just as the majority of Australians know Aboriginal people only in the abstract terms of those representations that circulate in the public sphere, so too ‘the gallery’ along with other institutions of ‘Canberra’ remain abstractions for Aboriginal people living in remote areas until circumstances refigure them as personalised, tangible forms. The spaces of national identity-making and the lives of remote Aboriginal people are deeply entangled. The question that continues to agitate at the core of Australian politics is one of how and to what degree the abiding distance between them might be breached. The opening of the new National Portrait Gallery provides a potent experience for reflecting on these issues.

Melinda Hinkson teaches social anthropology and convenes the visual culture research postgraduate program in the Research School of Humanities and the Arts at the Australian National University. She is co-editor of three books, Coercive Reconciliation: Stabilise, Normalise, Exit Aboriginal Australia (Arena Publications, 2007), An Appreciation of Difference: WEH Stanner and Aboriginal Australia (Aboriginal Studies Press, 2008), and Culture Crisis: Anthropology and Politics in Aboriginal Australia (UNSW Press, 2010).

Acknowledgements

For helpful discussions and comments on earlier versions of this paper I am grateful to Jon Altman, Tim Bonyhady, Nigel Lendon, Valerie Napaljarri Martin and Andrew Sayers.

I would also like to thank Russell Smith and AHR’s two anonymous referees.

Notes

1 See Engledow for an overview of the corporate history.

2 The name of this township is deliberately elided in this essay.

3 Over the period of its development, while occupying a smaller and more restrictive space in Old Parliament House, the Gallery has participated in some modest ways in the creative redefinition of portraiture as a medium, strategically interspersing challenging exhibitions with more conventional displays. The most controversial exhibition mounted in the previous location was Reveries: Photography and Mortality. See Ennis.

4 Andrew Sayers left the Gallery in June 2010 to take up the position of Director of the National Museum of Australia.

5 Gordon Bennett’s statement is available at <http://www.portrait.gov.au/gallery/portmnth/february/portmnth.htm> Accessed 12 Feb. 2009.

6 Kylie Message, for example, writes ‘themes of dialogical flow and exchange have become ubiquitous in museum practice in the last fifteen years or so. They have been employed as strategies integral to the production of museological spaces, exhibitions and public programmes globally, and form a plank that is central to the development of the “new museology” over that period’ (Message 755).

7 Michael Desmond, senior curator, National Portrait Gallery, personal communication 16 March 2009.

8 See Lydon for a detailed and compelling study of Kruger’s work at Corranderrk.

9 Under the terms of the Intervention half the welfare payments of all Aboriginal people living in the Northern Territory are quarantined by use of a ‘Basics Card’ which can only be used for purchasing designated goods at particular licensed stores in the Northern Territory. Travelling interstate presents particular problems of cash flow.

10 Open Air: Portraits in the Landscape ran from 5 December 2008 to 1 March 2009.

11 Here I invoke Ghassan Hage’s argument in Against Paranoid Nationalism.

Works Cited

Altman, Jon and Melinda Hinkson. ‘Very risky business: the quest to normalise remote Aboriginal Australia.’ In Risk, Responsibility and the Welfare State. Eds. G. Marston, J. Moss and J. Quiggin. Melbourne: Melbourne UP, 2010. 185-211.

—, eds. Coercive Reconciliation: Stabilise, Normalise, Exit Aboriginal Australia. Carlton North: Arena Publications, 2007.

Bardon, Geoffrey. ‘The men’s story.’ In Papunya: A Place Made After the Story. The Beginnings of the Western Desert Art Movement. Ed. Geoffrey Bardon and James Bardon. Melbourne: Miegunyah Press, 2004.

Bourdieu, Pierre and Alain Darbel. The Love of Art: European Art Museums and their Public. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1990.

Clark, T.J. Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing. New Haven: Yale, 2006.

Dibley, Ben. ‘The museum’s redemption: contact zones, government and the limits of reform.’ International Journal of Cultural Studies 8.1 (2005): 5-27.

Edwards, Lorna. ‘Time to get off your arses: Rolf’s advice to Aborigines’. The Age, 2 December 2008. Available at http://www.theage.com.au/national/time-to-get-off-your-arses-rolfs-advice-to-aborigines-20081127-6k28.html?page=-1 Accessed 20 Feb. 2009.

Elkins, James. The Object Stares Back: On the Nature of Seeing. San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1997.

Engledow, Sarah. ‘The National Portrait Gallery and its collection.’ The Companion. Canberra: National Portrait Gallery, 2008. 2-9.

Ennis, Helen. Reveries: Photography and Mortality. Canberra: National Portrait Gallery, 2007.

Everett, Christine. ‘Welcome to country … not.’ Oceania 79.1 (2009): 53-64.

Giddens, Antony. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1990.

Hage, Ghassan. Against Paranoid Nationalism: Searching for Hope in a Shrinking Society. Annandale: Pluto, 2003.

Hinkson, Melinda. ‘Media images and the politics of hope.’ Culture Crisis: Anthropology and Politics in Aboriginal Australia. Ed. Jon Altman and Melinda Hinkson. Sydney: UNSWP, 2010. 229-47.

—. ‘Warlpiri drawings collected by Mervyn Meggitt.’ Likman’mirri—Connections: the AIATSIS Collection of Art. Exh. cat. Canberra: AIATSIS, 2004. 32.

Kowal, Emma. ‘The politics of the gap: Indigenous Australians, liberal multiculturalism and the end of the self-determination era.’ American Anthropologist 110.3 (2008): 338-48.

Lattas, Andrew. ‘Aborigines and contemporary Australian nationalism: primordiality and the cultural politics of otherness.’ Social Analysis 27 (1990): 50-69.

Lydon, Jane. Eye Contact: Photographing Indigenous Australians. Durham: Duke UP, 2005.

Manne, Robert. ed. Whitewash: On Keith Windschuttle’s Fabrication of Aboriginal History. Melbourne: Black Inc. Publishing, 2003.

McQueen, Humphrey. ‘“In for ‘higher art’ I’d go”: At the National Portrait Gallery.’ Australian Book Review, May 2009: 41-3.

Merlan, Francesca. ‘Aboriginal cultural production into art: the complexity of redress’. In Beyond Aesthetics: Art and the Technologies of Enchantment. Ed. Chris Pinney and Nicolas Thomas. Oxford: Berg, 2001. 201-235.

Message, Kylie. ‘Reflecting on the new museum through an Antipodean lens: The Museum of Sydney and the “ Imaginary Museum ”.’ Third Text 22.6 (2008): 755-68.

Morphy, Howard. ‘Mediating forms—the spiritual dimension of Yolngu portraiture.’ Unpublished paper presented at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, 12 February 2009.

National Portrait Gallery http://www.portrait.gov.au/site/Vision_Statement.php (accessed 18 February 2009).

Povinelli, Elizabeth. The Cunning of Recognition. Durham: Duke UP, 2001.

Reconciliation Australia. Australian Reconciliation Barometer Comparative Report: Comparing the Attitudes of Indigenous People and Australians Overall. Canberra: Auspoll, 2009. Available at: http://www.reconciliation.org.au/home/reconciliation-resources/australian-reconciliation-barometer 2009. Accessed 20 Feb. 2009.

Rudd, Kevin, PM. ‘Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples.’ Canberra: Parliament of Australia, 13 February 2008. Available at www.aph.gov.au/HOUSE/Rudd_Speech.pdf Accessed 17 Feb. 2009.

Sayers, Andrew. Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century. Melbourne: Oxford UP, 1994.

—. Open Air: Portraits in the Landscape. Exh. cat. Canberra: National Portrait Gallery, 2008.

Sutton, Peter. ‘Stanner’s veil: transcendence and the limits of scientific inquiry.’ In An Appreciation of Difference: WEH Stanner and Aboriginal Australia. Ed. Melinda Hinkson and Jeremy Beckett. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2008. 115-25.

Taylor, Charles, ‘The politics of recognition.’ In Multiculturalism: A Critical Reader. Ed. David Goldberg. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994. 75-106.

Trofimov, Yaroslav. ‘“Tough love” in the outback.’ The Wall Street Journal, 17 January 2009. Available at http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123214753161791813.html Accessed 20 Feb. 2009.

Windschuttle, Keith. The Fabrication of Aboriginal History. Sydney: Macleay Press. 2002.

Woodall, Joanna, ed. Portraiture: Facing the Subject. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1997.