By Mandy Treagus

© all rights reserved. AHR is published in PDF and Print-on-Demand format by ANU E Press

This paper concerns Makereti Papakura (1873-1930), celebrity tourist guide of Rotorua, performer, tour organiser, English landed gentry and ultimately anthropologist. Known as ‘Maggie’ to tourists who found Makereti a challenge, she was famous enough in the first decade of the twentieth century in Aotearoa/New Zealand for a letter addressed to ‘Maggie, New Zealand’ actually to reach her (Makereti Papers). Though still well known in Aotearoa, she is little remembered elsewhere. Makereti made three voyages from New Zealand to England, and each is indicative of choices she made about her roles and the ways in which she would or would not be represented. The first was in 1911 as the organiser of a Maori concert party attending exhibitions associated with the Coronation of George V and Queen Mary in June of that year. The second was soon after in 1912, when she returned to marry the Englishman, Richard Staples-Brown, and take up residence on his estate in Oxfordshire. Later, having begun anthropological studies at Oxford University, research for her thesis brought her back to her home village of Whakarewarewa for six months of intensive field work and consultation in the first half of 1926. That voyage back to England in July 1926 was her last. In these quite distinct phases of her life, Makereti undertook a variety of tactics in response to both the range of colonising forces arrayed against her and the particular opportunities afforded her as a woman of mixed race. In this article I seek to examine how such tactics, though considerably varied over her lifetime, demonstrate a continuing assertion of Makereti’s own agency; because of her identification with the Arawa people, this invariably resulted in an accompanying assertion of Te Arawa agency.

I will refer to my subject as Makereti throughout. This is not to indicate a diminution by assumed familiarity that is sometimes attached to women, when their forenames are used almost exclusively instead of their surnames. She was born as Margaret Thom, married Joseph Dennan in 1891 (Stafford 53), and died, having remarried, as Margaret Staples-Brown, but her most commonly used surname was something of a stage name: Papakura. When a tourist in Whakarewarewa demanded to know her ‘Maori’ name, she provided one, taken from the nearby Papakura geyser (Stafford 56). Her brother and sister, also performers, came to be known by this name as well. But she was Makereti, the Maori pronunciation of Margaret, or its shortening Ereti, for all of her life (Diamond 13).

Born of an English father and Arawa mother in 1873, Makereti was taken at an early age to live with her maternal uncle and aunt, following the practice of whangai in which children are raised by relatives. They spent much of their time in the bush surviving by traditional hunting, gathering and farming. As part of this upbringing, she was taught, and became proficient in, oral traditions by the age of nine, especially whakapapa (genealogy)—she could recite the lines from which she was descended and knew all the inter-relationships of her hapu—and the stories of her Maori ancestors (Dennan 47-8). Te Arawa scholar, Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, claims that portentous signs at her birth led the old people to induct her into ‘the special knowledge of Ngati Wāhiao and Ngati Tūhourangi … the treasures’ (146). According to her daughter-in-law, Guide Rangi Dennan, Makereti was regarded as ‘“te aho ariki”, the first born of the eldest line of noble and sacred ancestors … a descendant of all the chiefs back to the seven canoes, and to the gods themselves’ (47). Each stage of Makereti’s life reflects a very different approach to how she would survive economically and how she would present herself to others. These stages in turn meant different choices about presenting Maori to others, as much of her work, life and finally research were explicitly concerned with Maori self-representation, albeit in vastly different ways.

Tourist Enterprises at Home

The village of Whakarewarewa, adjacent to modern day Rotorua, was where Makereti made her home after leaving school. In terms of sustaining themselves, with the loss of land and a developing currency-based economy, many Tūhourangi and Ngāti Wāhioa, Te Arawa hapu (sub-tribes), turned to tourism in the rapidly changing country. With much of their ancestral lands on areas of geothermal activity, the village of Whakarewarewa had a small tourism industry functioning while she was a child, charging 3/- per person to cross the bridge into the village to see the geothermal features (Diamond 24). The village expanded to take in relatives made homeless by the eruption of Mt Tarawera in 1886; they suffered the loss of their significant income from tourist guiding on the Pink and White Terraces when these were destroyed in the eruption. Pressure came from government manoeuvres to take control of the tourist industry by acquiring more land; in fact, by ‘the turn of the twentieth century, the government owned most of the geothermal features around the Whakarewarewa village’ leaving the people in the village even more dependent on building an income base from other tourist-related activities (Diamond 39). Instead of functioning as entrepreneurs controlling tourist attractions, ‘Te Arawa had been reduced, as a result of the Crown’s purchase activity, to little more than objects of curiosity for visiting tourists’ (O’Malley and Armstrong 219). Without control of the land, guiding and performance became the chief means of income: that and opening the village itself as a display. Once most avenues for income were cut off by pakeha and Government tactics, the village was extremely poor, even suffering an outbreak of typhoid (O’Malley and Armstrong 215-23).

Makereti was well-placed to play a prominent role in Whakarewarewa’s challenging economic circumstances and changing tourism industry; she had initiative, confidence and adaptability and she also spoke excellent English. Her father had taken over her education at the age of ten (Northcroft-Grant); she spent one year in an English style school, time with a governess, a stretch at the Rotorua District School and three further years at Hukarere, an Anglican boarding school for Maori girls in Napier (Makereti Papers; Stafford 53). She had grown up speaking only Maori and her brother teasingly called her a ‘Black Maori’ because of this (Diamond 25), but she soon showed an aptitude for understanding pakeha life and values; as she later told an English reporter of her first year away at school when she was teased: ‘That was the most horrible year of my life, but I learnt how you people think’ (Te Awekotuku 147). Going from being the treasured child in the bush to school in a vastly different cultural and language context must have been difficult, but Makereti clearly learnt and adapted. In this comment, she identifies explicitly as Maori and notably not as pakeha, perhaps not surprisingly as she was at the time a visiting performer in a Maori troupe, but as a child of mixed parentage she also chose to identify in other ways, and participated in the wider culture. For example, she was entitled to register as Maori on the electoral role in order to vote for specific Maori seats in Parliament, yet she chose to register for the ‘European’ seats, despite campaigning for Apirana Ngata, the Maori candidate (Diamond 15). Her identification with her Maori heritage did not prevent her from participating in a wider colonial mobility that was not confined to colonising figures (who often moved from post to post), but also to those who might be considered colonised.

With village income dropping to about a tenth of what it had been by 1898 (O’Malley and Armstrong 219), the compulsion to find alternative employment on almost no land was pressing. Despite her mixed parentage and relatively privileged education, Makereti was not immune from these pressures. She and her sister Bella gradually took charge of the Maori concert parties and guiding through the geo-thermal sites. By the time the group left for a London tour in 1911 they were seasoned performers, and Makereti had been working as performer, manager and promoter for some years. Tourism brought with it great intrusions from visitors though, with the village itself being one of the attractions; this had the effect of constructing Whakarewarewa as a site for the display of its inhabitants as ‘native objects’ and Makereti played a prominent role in this. By the time she came to public attention, Makereti was an accomplished young woman, proficient in upper-class social interactions and culture through engaging with visitors to the village, as well as maintaining her deep knowledge of Maori genealogy and tradition. From early adulthood, she moved in and between worlds with a facility few could match. A bystander in Melbourne in 1910 reported on how she entered a restaurant in Maori dress and ordered the best French champagne; he exclaimed: ‘By Jove! She knows what’s what’ (Table Talk, 10 November 1910). More significantly, her knowledge and genealogy brought her respect in her home community. But she had another quality, that Polynesian marker that is easy to identify but hard to quantify or describe: mana (authority, power, charisma, sacredness), which had an impact on those of any race or class who encountered her.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, reflecting these qualities, Makereti underwent a change in public status and this is seen in the postcards produced during the time. The period marks ‘a golden age for postcards’, with ‘billions in circulation’, especially in Europe and the US (Desmond 43). Postcards functioned in synecdochic relationship to the tourist sites they referenced, and in order to do so they needed to be distinctive and recognisable (Desmond 43-4). As the leading guide of the village, Makereti mediated the tourist experience and many of the postcards sold featured images of her. These postcards show a development in both her agency and the power she increasingly took over her own representation, albeit within limited discourses, as she moves from objectified Maori maiden to full-blown national celebrity, in charge of much of her own promotion. Early images negotiate with contemporaneous notions of the ‘native’, the ‘south seas belle’, the ‘Dusky maiden’ and the ‘primitive’, especially as these interact with the tropes of colonial photography (Jolly 99-122; Tamaira 1; Torgovnick). One of the more common of these tropes was the tendency for indigenous people to be ‘identified only by costume or perhaps a single cultural artefact’ (Whittaker, ‘A Century’ 426). In the following photographs, we see the use of Maori costume and the single artefact as one of the strongest guiding principles in the construction of images. Max Quanchi mentions the use of such ‘types’ in Samoan photography of the same period, in which studio poses of young men or women wearing traditional headdresses and holding ‘clubs or knives’ had already become ‘a cliché’, widely available in the region, including New Zealand, by 1907 (208).

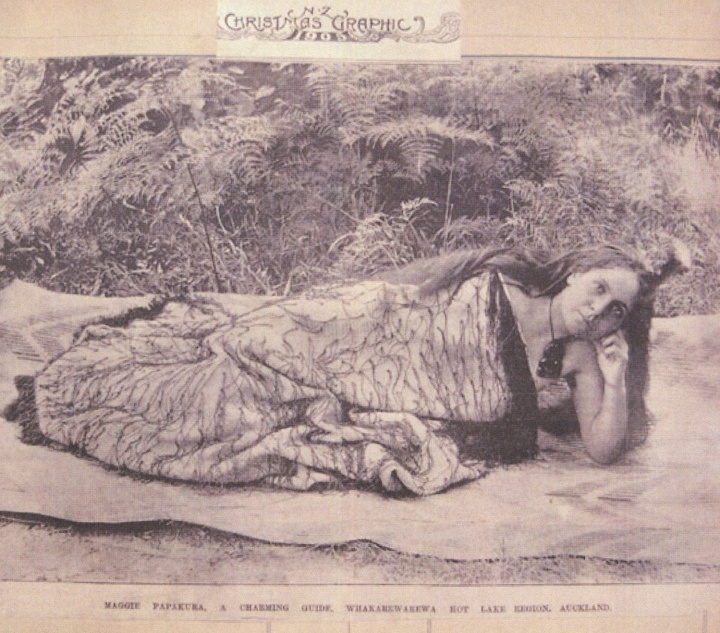

Figure 1. Cover of New Zealand Christmas Graphic, 1908, from photo taken & used in Auckland Weekly News, 22 March 1901. Reproduced with permission of Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries. AWNS-19010322-12-1.

Figure 1. Cover of New Zealand Christmas Graphic, 1908, from photo taken & used in Auckland Weekly News, 22 March 1901. Reproduced with permission of Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries. AWNS-19010322-12-1.

This image (Figure 1) was first used in 1901 before the royal visit of the Duke and Duchess of York brought Makereti to national attention later the same year, and was not, to my knowledge, used as a postcard, but rather featured in the press. The korowai (woven cloak), hei tiki pounamu (greenstone carved human pendant) around the neck, and huia feather1 worn in her hair evoke Maori identity for New Zealand viewers, but they also suggest a generalised ‘native’ one, especially for those outside the country. (Just as exhibitions of the time often used artefacts, dances and even peoples interchangeably in ‘native’ performances, so in colonial photography, ethnographic accuracy was not always paramount.) Makereti lies on her side on the woven mat, looking somewhat uncomfortable with her head propped on her hand, yet gazing back toward the viewer. Her pose, while evoking the ‘sexually saturated figure of the Polynesian woman’ (Jolly 99), with hints of nakedness under the cloak, does so within the bounds of respectability.

The setting, among the ferns, draws an affinity with nature, supposedly a quality of the ‘native’ and of the ‘primitive’ (Torgovnick 8). Rhythmic continuity between Makereti’s hair, the tassels of the cloak (designed to move with the wearer), and the surrounding ferns and grasses accentuates this. The lack of markers of time, suggesting an ahistorical space, furthers the notion that the ‘native’ is not part of the contemporary world and therefore insignificant in national life. A similar strategy can be seen in the representation of Hawaiians during the same period. Hawaii’s burgeoning tourist industry was predicated, especially in visuals, on the construction of a dichotomy between the ‘modern’ visitor and the ‘primitive’ Hawaiian: ‘Such a strategy lays bare the process of constructing the primitive as the necessary complement to modernity by denying the coevalness of the viewer and the viewed’ (Desmond 40). The practice of ‘decontemporizing’, as ‘a necessary way of “nativizing” the Native Hawaiian population’ (Desmond 40) can also be seen in these New Zealand images featuring Makereti, in which no signs of contemporary life are in evidence. The tourist viewer is free to see the subject of the photograph as ‘native’ in contrast to his or her position in modernity. Whittaker claims that ‘It was the photography related to tourism that disseminated a pervasive visual discourse about race’ (‘Photographing Race’ 117). There had already been a substantial history of photography in which ‘types’ were constructed and explained, through specific discourses, in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Within a supposedly educational context, ‘types’ were explained in ethnographic and biological terms, continuing the Victorian preoccupation with classification and taxonomy, and often perpetuating a vision of the world which was Social Darwinist in drive. For colonisers, this was part of the technology of racial ‘science’ that propped up unequal systems of power. As Christopher Pinney so persuasively argues, the truth claims of both anthropology and photography were fragile at best and needed specific textual strategies in order to erase the signs of their own construction (74-91).

Yet there are other ways of reading the image. Many would know the significance of the ancestral hei tiki around Makereti’s neck, and the huia feather in her hair as evocation of her birth and status as ariki (noble). Though not in full control of the image, Makereti can be seen to be asserting her identity, however it might be read by others. Similarly, Bella Papakura countered the potential objectification of her village and its inhabitants when guiding by insisting on ‘treating those guided around Whakarewarewa not as tourists but as manuhiri (visitors)’ (O’Malley and Armstrong 229). Such understandings promote a counter discourse in which the display of locals for outsiders, for pay, could maintain continuity with cultural traditions of hospitality while resisting modern commodification of people as objects. These tactics are important tools in countering the ways in which the long drawn out process of colonialism undermined both identity and dignity. During personal interactions it was much easier to resist; in static forms, such as photographs, it was more difficult, especially when images were used on postcards for sale that were decontextualised by circulation.

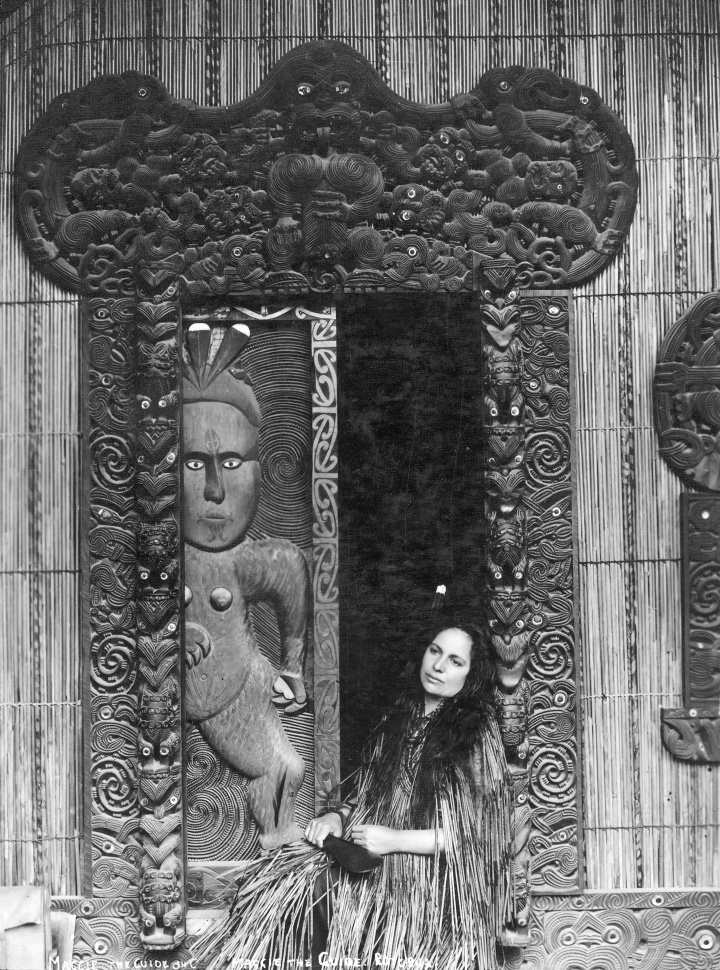

Figure 2. c. 1901-1910. At Te Raura meeting house, Whakarewarewa. William Andrew Collis. Reproduced by permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ. PAColl-6407-83.

Figure 2. c. 1901-1910. At Te Raura meeting house, Whakarewarewa. William Andrew Collis. Reproduced by permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ. PAColl-6407-83.

In this image (Figure 2), Makereti appears with a single artefact, in this case a mere pounamu (greenstone short-handled weapon). While potentially signifying readiness for battle, weapon artefacts in the genre of tourist postcard are seen to signify ‘native’ rather than antagonism, as there are no indications of aggression: quite the contrary, as Makereti looks away from the camera, allowing the viewer unimpeded gaze. As a representative of Maori at Whakarewarewa, this apparent submission speaks to the function of the whole group, reassuring the white viewer that there is no threat here, either to the colonial eye or to colonial activity. The superb carving of Te Raura meeting house behind her, and indeed dwarfing her, accentuates her position as part of the display that is the tourist experience in the village. Once again there is rhythmic continuity between Makereti and this backdrop, though rather than indicating affinity with nature, she is here positioned to show affinity with traditional culture, as exemplified by Te Raura, with the long vertical lines of her piupiu (skirt), blending with the vertical slats that make up the walls. The viewer’s eye is drawn to Makereti: she is framed by the doorposts, and juxtaposed with the strong female figure on the left, while the darkened interior (which remains unseen by the viewer), draws attention to her face. Yet a range of elements also suggest Makereti’s power, despite the invitation to the viewer to gaze. This is especially seen via the correspondence with the female ancestor figure, also shown wearing huia feathers and directly gazing at the viewer; it is further emphasised by the other challenging eyes in the carvings on the door posts. While the meeting house backdrop may have been used for its scenic and exotic function by the photographer, it also speaks of heritage, lineage and cultural assurance.

Figure 3. c. 1910. Makereti (Maggie) Papakura. William Henry Thomas. Reproduced by permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ. G-3055-1/1.

Figure 3. c. 1910. Makereti (Maggie) Papakura. William Henry Thomas. Reproduced by permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ. G-3055-1/1.

This image (Figure 3) shows Makereti in bare feet, wearing a kahu kiwi (kiwi feather cloak) over her piupiu, and holding a taiaha (staff-like weapon), and it makes no reference to any contemporary aspects of her life; rather, she is aligned with the landscape, the thermal steam rising around her, as wisps of her hair lift in the breeze. This primitivist depiction shows Makereti as outside any specific time frame, and her gaze, away from the viewer and into the distance, once again suggests that she is unconcerned with the present, as well as submissive to the gaze. As ‘woman’ and ‘native’ this conflation with the landscape is doubly inscribed. Maori might read this image differently though. Once again, the feather signals her birth as ariki, and the extremely precious kahu kiwi cloak is a taonga (priceless heirloom) with connections to both ancestors and spiritual forces, as is the hei tiki. Identification with ancestral land and its features can be read as an assertion of rights, ownership and privileges, rather than as a submission to colonising forces. Holding the taiaha, which is decorated with tufts of hair and carving, and looking relaxed, Makereti is proclaiming her status as chiefly (Te Rangi 277), and potentially her right to speak ceremonially as a result of this.

In both Figures 2 and 3, the images also engage with a wider history of the Polynesian woman as the object of voyeuristic gaze and fantasy. This dominant history of representation has seen the Polynesian woman over-inscribed, both in literary and visual history, as not only inherently sexual but sexually available, especially to the white male. From Cook and Banks, to Melville, Gauguin, Becke, London, Michener and in numerous filmic and photographic representations up until the present time, a set of tropes has worked to reinforce these perceptions and to encode the female Polynesian body in quite limited ways, as outlined by Margaret Jolly (99-122). In these images, Makereti’s long hair, flowing free in contrast to pakeha conventions of respectability, links her with this tradition, as do the glimpses of skin on her shoulders and feet (Jolly 106-7). That these photos are constructed in deliberate alignment with such conventions is suggested by the fact that in everyday life Makereti wore her hair up, sometimes in plaits, and usually covered with a cerise head scarf, a style that became something of a uniform for Whakarewarewa guides. She also often wore typical western dress of the time, again suggesting identification with a wider colonial identity, even expressing a colonial cosmopolitanism. While Makereti can be seen to resist dominant conventions about representing the Polynesian woman by remaining fully clothed and to some extent in control of the image, it is difficult to escape the historical over-inscription. Even aside from this particular history, the subject’s averted gaze encourages a voyeuristic gaze in the viewer, as it allows us to look without the return gaze of the subject.

Makereti’s diary entries of 1907-8 show that she organised photographic sittings and ordered the printing of photographs and postcards for sale in the village and beyond. That conventions around representation are on display in these postcards is not surprising, yet at the same time Makereti shows a high level of control over the production and distribution of the images. One image that has become well known recently is that shown in Figure 4.

- Figure 4. 1905. E.W. Payton. Rotorua Museum Te Whare Taonga o Te Arawa. OP-1971. Reproduced by permission of the Rotorua Museum of Art & History, Te Whare Taonga o Te Arawa, Rotorua, New Zealand.

This photo, which to my knowledge was not made into a postcard, shows her looking defiantly in direct address at the photographer, apparently tired of the whole process of performing the role of exotic photographic model. Despite having similar elements to the earlier figures, nothing about this image connotes lack of control, objectification or submission. Rather, we see a woman who is tired of the routine, but going through with it anyway. Increasingly, the kinds of images Makereti chose for distribution and those which appeared in the press shift from those connoting universalised ‘native’ or ‘Polynesian belle’ to distinctive ones indicating the specificity of Makereti’s world.

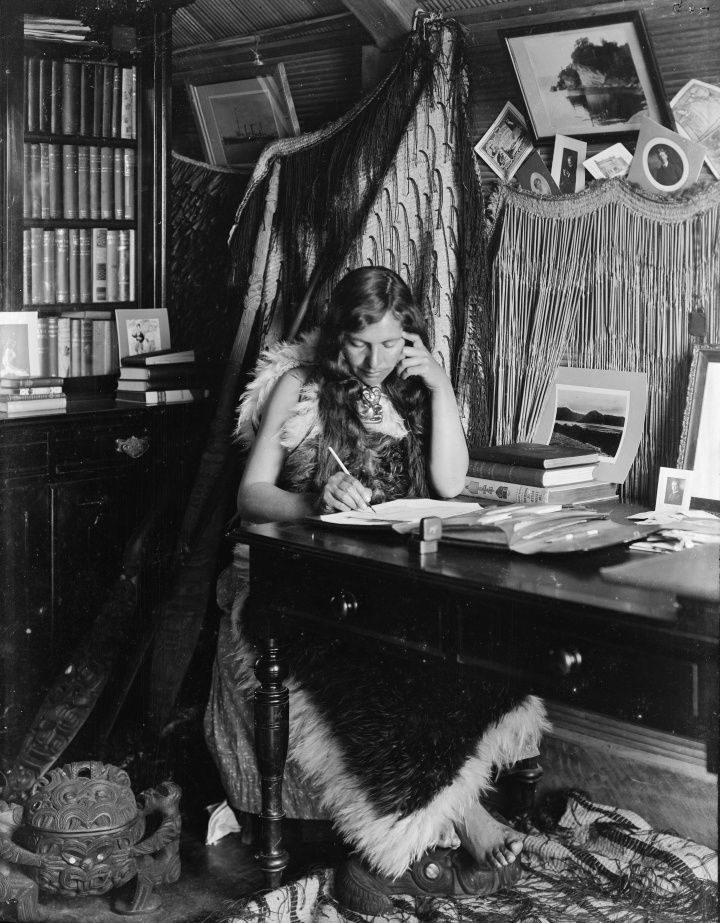

Figure 5. c. 1910 in her whare. William Henry Thomas Partington, Auckland Star Collection. Reproduced by permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. G-3054-1/1. Full size image.

Figure 5. c. 1910 in her whare. William Henry Thomas Partington, Auckland Star Collection. Reproduced by permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. G-3054-1/1. Full size image.

This photograph (Figure 5) moves away from the primitivism and stereotypical images previously shown to present a quite different conception of Makereti. The image is just as constructed, but its combination of elements evokes a specific personality rather than the over-inscribed ‘dusky maiden’ (Tamaira 1). Signifiers of the ‘native’ are still prominent in the image; Makereti wears the heirloom hei tiki and kahu kiwi feather cloak, and goes barefoot while surrounded by carved taonga, notable among which is the kumete whakairo (carved lidded presentation bowl)

near her feet. There are also cloaks, both korowai and piupiu, hanging from the wall, and another korowai under her feet. But the organisation of these clothing items now evokes home life more strongly than exoticism, as they are slung up out of the way. The traditional items are contextualised in a way they were not in previous images; they can be read as possessions by a western viewer (even if varying understandings of possession and material culture in Maori life cannot so easily be read). But Makereti also wears a dress under the cloak, along with long flowing hair, blending with the kiwi feathers, and bare feet. One might consider the composition as ‘hybrid’, though this suggests an artificial lifestyle binary in which Maori were out of the contemporary world. Makereti and her people were part of the colonial world, albeit one constrained by the depredations of colonisation, rather than existing in ahistorical cultural isolation; hence hybridity is an inaccurate cultural description. I also take Albert Wendt’s point that ‘“Hybrid”, no matter how theorists, like Homi Bhabha, have tried to make it post-colonial, still smacks of the racist colonial’ (Wendt).

The image is significant because here Makereti engages with signs of education, in the form of desk, books and writing set, hinting at her future life as a student and writer. These place her in a particular time and place, as do the array of cards from around the world and the selection of photographs. The titles of some her book collection are visible: The Living Rulers of Mankind, by H.N. Hutchinson (1902); The History of ‘Punch’, by M.H. Spielmann (1895), and Kim, by Rudyard Kipling(1901) are notable. The former is a contemporary overview of the world’s rulers, the second implies a metropolitan sensibility, while Kipling’s account of imperialism, ‘the great game’ and cross-cultural masquerade, is another sign of the mobility of colonial culture that Makereti participated in. She is occupied with writing, without acknowledgement of the camera, but there is no sense of submission in this; rather, she demonstrates her agency and engagement with the wider world. Some newspaper readers would have been familiar with her letters to the press defending Maori haka performances when they were attacked for being indecent and crude (Diary). The image indicates not so much a transition in her own life, but rather a change in the representation of it. Makereti’s persona came to signify much more than the tropes of colonial photography as she moved into celebrity rather than stereotype. There was enough public interest in her for shots like this of her new carved home Tuhoromatakaka to feature ‘in photo spreads in the picture papers during 1910’ (Diamond 97). Celebrity life is ultimately one she rejects, but it was to have a final expansive phase on tour to London for the Coronation.

The London Tour

The tour was organised after repeated requests from entrepreneurs, and Makereti negotiated with an Australian syndicate regarding pay and conditions. The troupe included a brass band, a quartet, and the singer Iwa, who was met with rapturous responses wherever she sang and who stayed in London to have a music hall career for several years afterward as ‘Princess Iwa’. The Maori carved village was also open for visitors to tour, with the quotidian activities of its occupants seen to be an authentic depiction of Maori village life. Ambivalence on the question of human displays in these exhibitions was indicated in the British press by comments such as the following, which despite its general disapproval still indicates interest: ‘In spite of the ransacking of the world that goes on to give London savage thrills, we have rarely seen Maoris here’ (Manchester Daily Guardian, 31 May 1911). While the exhibitions associated with the Coronation were having their runs in 1911, the city also played host to the First Universal Races Congress, held at the University of London, 26-29 July 1911 (Holton). The apparent extremes occupied by these two events—native displays on the one hand and the Congress on the other—indicate the range of thinking about race and empire at the time, but they also present a somewhat false dichotomy. One might suppose that the Congress would break down racial stereotypes while the display villages reinforced them, but in the case of this Maori tour it was not so simple. Exposure to those from different places and cultures in the native village did not always serve as an object lesson in European or American superiority, but could rather begin to break down assumptions of superiority. It also provided a unique opportunity for the metropolitan public to find itself reflected back through eyes that critiqued, as well as praised its achievements. For a touring indigenous party, this particular group received an enormous amount of press, and through it we can read their public impressions of London and English culture, among other things.

Initially the press positions the group as completely Other to those from the metropolitan centre. Consider this page from the Illustrated London News detailing the Maori response to the royal opening of the Festival of Empire: ‘New Zealand’s Primitive Inhabitants Greet Their King’:

Twice the Royal carriage halted for their Majesties to gaze upon the scene, and at the second time there was a strange and thrilling episode. … These dark children of the Southern seas, with their long black hair and lustrous eyes, and brown, bare limbs, women as well as men in their native dress, seemed to go mad upon the moment of seeing the great White Chief. They yelled to him a strange and wild chant, dancing up and down, and beating the turf with their naked feet, waving their war clubs, laughing and clapping their hands and shouting continually with extraordinary excitement. (20 May 1911)

This simplistic projection of primitivism onto the group and their performance of the haka, along with the assumption of their subservience to the King, indicates that initially their position as childlike and unsophisticated was very strongly entrenched in the popular press and, one assumes, in its readership. Bare skin and long, unbridled hair are also emphasised, evoking the long tradition of ‘dusky maidens’. This was typical of many early depictions of the Maori group, and their exoticism of course makes it more sensational. What is notable about the London press though, is how on closer acquaintance it changed its tune.

Once Makereti had actually been interviewed and reporters had the chance to engage with her and other members of her party, the tone of press reports changed markedly; this statement from a British journalist is typical:

Who is the most accomplished, the most gracious, the most winning stranger in London this great Coronation season? Maggie the Maori. If you don’t believe me, if you think I am exaggerating, if you find it difficult to understand how a Maori can be accomplished, gracious, or winning, go to the Crystal Palace, visit the Maori Village, and try to get a few minutes of conversation with Maggie, the unanimously elected Chieftainness of the Tribe. (The Sketch, 4 May 1911, 194)

Her social facility and range of cultural capital ultimately endeared her, and much of her touring party, to the press. A reporter commented that ‘Looking at her as she sat … back in her chair, wearing an everyday English white silk blouse and dark skirt, it was difficult indeed to imagine that her surroundings were in any way novel to her’ (Daily Mail, 1 May 1911). Like many journalists, this writer was at pains to emphasise her facility in the metropolitan centre, and though there are inherently imperial assumptions underlying the surprise expressed, the writer is unable to dismiss Makereti as a simple colonised Other. Accordingly, Makereti also assumes she has a real place in the Empire being celebrated and that she is not cut off from the imperial inheritance. She seems to take the empire at its word, in its rhetoric of civilisation, conversion and progress, speaking of England as ‘the old country’. ‘We, too, regard it as “home,” like other Colonials’, she told the Daily Chronicle (1 May 1911). It is almost like a dare to the imperial centre, to make good on its promises. Though the complications of coming from a tribal group that was kupapa (had fought with Crown forces in the wars) is beyond the scope of this article, it may have played a role in this apparent identification (Belich 286). During this tour Makereti became a celebrity in Britain; by September it was claimed that she was receiving over 300 letters a day from the British public (‘John Bull’).2

However comfortable she may have appeared as spokesperson and manager for the touring party, it was a life she was soon to leave behind. The tour was a financial disaster for its backers, despite the hard work of the performers themselves (Stafford 56). While there, Makereti became reacquainted with Richard Staples-Brown, a wealthy farmer she had met in New Zealand, who owned several properties in Oxfordshire. In accepting his offer of marriage, she was very clear that this would mark an end to her life as a celebrity. The marriage offered financial security which allowed her to leave the day to day work of guiding and managing cultural performances. Instead, she moved into a manor house, had a club in London, household servants, and a life of relative luxury, at least initially. She was also removed from New Zealand village life, and this may have been welcome after conflict and violence which followed her return from the London tour, when half of the party stayed on in London, much to the disappointment of their relatives (Makereti Scrapbook).

From the time of her acceptance of the marriage proposal, she explicitly refused celebrity life. She was extremely annoyed when her engagement was announced in Britain and Aotearoa/New Zealand before she arrived home, and after the wedding she wrote to her friend T.E. Donne, the former secretary for Tourism in Aotearoa/New Zealand: ‘Very few people know [I] am in Eng & I do not want anything to go to the newspapers. … Besides I had retired from public life many months ago & have no wish to have my name in print again’ (Diamond 130). In 1924 she refused to take part in a Maori Pageant in London, insisting in a letter that ‘My old name must not be used in either shape or form whatever’ (Makereti Scrapbook qMS-0621, 73). Eventually she acquiesced and took part, writing, ‘I must try & not let them have the Maori misunderstood. … Only for this reason did I join them’ (qtd in Diamond 145). The demands of upper-middle class respectability in England may have also influenced her decision to withdraw, but it seems that once she had the means to stop the performing life and its accompanying celebrity status, she did so. Along with her desire to retire from public life, the drive to protect Maori culture continued, but it found its clearest outlet in anthropological studies at Oxford University.

The Anthropologist

In 1922, Makereti became an associate member of the Oxford Anthropology Society, and in 1927 joined the University to study anthropology. In the meantime, her marriage had ended and she was once again in financial difficulty until the divorce could be granted. Despite this, in North Oxford, and in each place she lived in England, she had a ‘New Zealand Room’, in which she hung her precious cloaks and stored many other taonga. She made a final trip back to New Zealand in the first half of 1926, living in her former house there. Her sister Bella was still involved in guiding and tourism, while Makereti had become a great lady who, her relatives recalled, ate with a knife and fork instead of her fingers. She used this trip to gather further anthropological data from her own people, before returning to the UK on her final crossing. Sadly, she died suddenly in 1930, just three weeks before her work was to be submitted as her thesis at Oxford.

The thesis, eventually published as The Old Time Maori, is an assertion of traditional knowledge and values. It begins, as many anthological studies would, with a description of tribal and family organisation. In line with traditional Maori values though, this is expressed in genealogical lines, whakapapa—her own—demonstrating her descent from four original chiefly lines. This is part of the oral history she learnt as a young child. In his introduction to her work, T.K. Penniman, her friend, who became curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum the year after it was finally published, recorded that ‘She wrote regularly to her people at home to make certain that they were willing to allow the publication of various facts, or that the facts were exactly right’ (Penniman 25). This is therefore something of a collaborative effort, as all anthropological projects are, though many are not fully acknowledged as such.

Pacific scholars White and Tengan have suggested that anthropological ‘disciplinary models and practices—from fieldwork to publication—have worked historically to authorize and reinforce dichotomies that separate native subjects from anthropological agents’ (389). There has been limited understanding of the roles of indigenous inquirers, who are usually cast as ‘native informants’, rather than scholars capable of analysing the material ‘correctly’. Accordingly, in contemporary reviews of her work, Makereti was largely dismissed by male pakeha anthropological reviewers. Ralph Piddington, for example, asserts: ‘Unfortunately, Makereti’s lack of any conception of what it is important to record about a primitive people, and the personal character of her approach, produce an incoherent and highly idealized picture of Maori life’ (78). Similarly, Eric Ramsden assumes that Makereti could not, as a woman, have the required knowledge to even write an anthropological account of her people: ‘Though members of her sex had a definitely honoured place in ancient Maori society, they were never the repositories of sacred knowledge’ (191). The breathtaking arrogance of these responses hardly needs commenting on. Makereti’s determination to write her own account of her people seems to have been partly motivated by the desire to correct misconceptions she found in the work of other scholars, but these misconceptions continued well after her death. Somewhat surprisingly, it is The Illustrated London News that demonstrates the clearest sense of what Makereti’s book had achieved, giving it a full page article entitled ‘Maori Life From Within: By An Oxford-Trained Chieftainess’: ‘Outside observation, however painstaking, of other people’s odd customs can never be so revealing as explanation from within’ (Squire 480).

In The Old Time Maori, Makereti is both the ‘native informant’ and the scholar. This is just one of the ways in which she disrupts the usual fieldwork paradigm. She also places value on aspects of Maori culture that had been ignored by male pakeha scholars, including some of the men she had assisted in writing their works. She writes of childbirth and placentas, menstruation and menopause, child rearing and marriage and of protocol and ritual. She outlines agricultural and farming practices, control of food resources, and shows that life was organised, planned and abundant. As she does so, she engages with other scholars, pointing out where practices have been described but misunderstood. There is a strong sense of writing back, in the postcolonial sense, to earlier and contemporary writers. She also refuses to record everything, choosing to keep some cultural elements secret. This explicitly includes karakia (prayers and incantations) that she regarded as being too sacred to include or if included to translate. Makereti felt no compulsion to make all of Te Arawa culture available to western anthropology. Fortunately Penniman, who oversaw the publication, was respectful enough to carry out her wishes.

He suggests that ‘So intimately bound up with her people was she, that she could not write their history without unconsciously writing her own’ (20). Rather than being an unconscious move, I would suggest that she still saw herself as inextricably part of the culture she wrote about, and that the division between individual and group identity is an assumption that has its basis in western traditions of individualism, and not in Maori ones. Mary Louise Pratt has coined the term ‘autoethnographic text’ to refer to ‘a text in which people undertake to describe themselves in ways that engage with representations others have made of them’ (7). While this is not a conventional autobiography, as an autoethnographic text The Old Time Maori challenges both fieldwork reports and conventional autobiography, by presenting identity as collective, grounded in oral tradition and resistive of existing studies. Despite its reception, Makereti’s work is increasingly referred to by Maori scholars today. In writing it Makereti comes full circle in the sense that she recalls her early life in the bush with deep affection, and also mourns its passing, and the passing of a lifestyle that was last prevalent in the nineteenth century.

The identities adopted by Makereti appear to take dramatically different forms over the course of her life, yet she worked with what she had, finding agency in each particular situation, however limited. Even when potentially cast as ‘native object’, Makereti employed ‘the performativity of the stereotype’ as a ‘prop’ on which to fashion identities that would be useful to her and her people (Apter 18). In doing so, she enacted the tactic outlined by A Marata Tamaira, ‘in which the dusky maiden, of her own volition, shifts shape and direction’ to forge her own subjectivity (3).

Mandy Treagus is Head of English and Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide. She researches Victorian, Australian and postcolonial literatures and film, and cultural history. Her work has appeared in the Journal of Postcolonial Writing, Kunapipi, Australasian Victorian Studies Journal, Outskirts and The International Journal of the History of Sport. Her current project explores the display of Pacific peoples in colonial exhibitions and has appeared in several edited collections.

Acknowledgements

I thank the Te Arawa Maori Trust Board for its encouragement of the project that led to this article, and also Makereti’s relatives, June Northcroft-Grant and Jim Schuster, for their generosity in sharing family stories. I also thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, as well as my colleague Ros Prosser for her encouragement and suggestions, and Carolyn Lake for her usual efficient assistance.

I would also like to thank the Auckland Libraries, New Zealand (Fig. 1), Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand (Figs 2, 3 and 5) and the Rotorua Museum of Art & History, Te Whare Taonga o Te Arawa, Rotorua, New Zealand (Fig. 4)

for permission to reproduce the images used in this essay.

Notes

1 The huia, or New Zealand wattle bird, is now extinct, with the last confirmed sighting in 1907, suggesting that to even own feathers at that time was a mark of status.

2 See Treagus and Diamond for more extensive discussions of the London tour.

Works Cited

Apter, Emily. ‘Acting out Orientalism: Sapphic Theatricality in Turn-of-the-Century Paris.’ Performance and Cultural Politics. Ed. Elin Diamond. London: Routledge, 1996. 15-34.

Belich, James. The New Zealand Wars: and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict. Auckland: Auckland UP, 1986.

Daily Chronicle, 1 May 1911. Makereti Papers.

Dennan, Rangitiaria, with Annabell Ross. [1968] Guide Rangi of Rotorua. Christchurch: Whitcombe & Tombs, 1986.

Desmond, Jane C. Staging Tourism: Bodies on Display from Waikiki to Sea World. Chicago: Chicago UP, 1999.

Diamond, Paul. Makereti: Taking Maori to the World. Auckland: Random House, 2007.

Holton, Robert John. ‘Cosmopolitanism or Cosmopolitanisms? The Universal Races Congress of 1911’. Global Networks 2.2 (2002): 153-170.

‘John Bull’. 16 September 1911. Makereti Papers.

Jolly, Margaret. ‘From Point Venus to Bali Ha’i: Eroticism and Exoticism in Representations of the Pacific’. Sites of Desire, Economics of Pleasure: Sexualities in Asia and the Pacific. Ed. Lenore Manderson and Margaret Jolly. Chicago: Chicago UP, 1997. 99-122.

Makereti Papers. Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford.

Makereti Scrapbook. Alexander Turnbull Library, qMS-0621.

Manchester Daily Guardian, 31 May 1911. Makereti Papers.

‘New Zealand’s Primitive Inhabitants Greet Their King’. The Illustrated London News, 20 May 1911. 745. Makereti Papers.

Northcroft-Grant, June. ‘Papakura, Makereti—Biography.’ Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Web. 1 July 2012. <http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biographies/3p5/1>

O’Malley, Vincent and David Armstrong. The Beating Heart: A Political and Socio-Economic History of Te Arawa. Wellington: Huia, 2008.

Papakura, Makereti. Diary 1907-8. Unpublished. Makereti Papers.

[Papakura] Makereti. [1938] The Old-Time Maori. Ed. Ngahuia Te Awekotuku. Auckland: New Women’s P, 1986.

Penniman, T.K. ‘Makereti.’ Makereti, The Old-Time Maori, 1938. Auckland: New Women’s P, 1986.

Piddington, Ralph. Review of The Old-Time Maori. Man, May 1940: 78.

Pinney, Christopher. ‘The Parallel Histories of Anthropology and Photography.’ Anthropology and Photography 1860-1920. Ed. Elizabeth Edwards. New Haven: Yale UP, 1992. 74-91.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London and New York: Routledge, 1992.

Quanchi, Max. ‘The Imaging of Samoa in Illustrated Magazines and Serial Encyclopaedias in the Early Twentieth-Century.’

The Journal of Pacific History 41.2 (2006): 207-217.

Ramsden, Eric. Review of The Old-Time Maori. Mankind 2.6 (1939): 191.

Squire, John. ‘Maori Life From Within: By An Oxford-Trained Chieftainess’. The Illustrated London News, 19 March 1938: 480.

Stafford, D.M. The New Century in Rotorua: A History of Events from 1900. Rotorua: Rotorua District Council, 1988.

Table Talk, 10 November 1910.

Tamaira, A. Marata. ‘From Full Dusk to Full Tusk: Reimagining the “Dusky Maiden” through the Visual Arts.’ The Contemporary Pacific 22.1 (2010): 1-35.

Te Awekotuku, Ngahuia. Mana Wahine Maori: Selected Writings on Maori Women’s Art, Culture and Politics. Auckland: New Women’s P, 1991.

Te Rangi, Hiroa (Peter Buck). The Coming of the Maori. Wellington, Maori Purposes Fund Board, 1949.

The Sketch, 4 May 1911, 194. Makereti Papers.

Torgovnick, Marianna. Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives. Chicago: Chicago UP, 1990.

Treagus, Mandy. ‘“Britons of the South Seas”: The Maori Visit to London, 1911.’ Projections of Britain. Ed. Heather Kerr & Lawrence Warner. Adelaide: Lythrum, 2008. 52-62.

Wendt, Albert. ‘Tatauing the Post-Colonial Body.’ Span 42-43 (1996): 15-29. New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre. 1 July 2012. <http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/authors/wendt/tatauing.asp>

White, Geoffrey M. and Ty Tawika Tengan. ‘Disappearing Worlds: Anthropology and Cultural Studies in Hawaii and the Pacific.’ The Contemporary Pacific 13.2 (2001): 381-416.

Whittaker, Elvi. ‘A Century of Indigenous Images: The World According to the Tourist Postcard.’ Expressions of Culture, Identity and Meaning in Tourism. Eds. M. Robinson et al. Newcastle: U of Northumbria and Sheffield Hallam, 2000. 425-37.

—. ‘Photographing Race: The Discourse and Performance of Tourist Stereotypes.’ The Framed World: Tourism, Tourists and Photography. Ed. Mike Robinson and David Picard. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2009. 117-38.