By Deborah Che

© all rights reserved

Understanding change in resource-dependent rural areas

Natural resource extraction is important to national economies such as Australia’s and to remote resource dependent areas within many developed nations. However, social scientists have long been concerned with the impacts of the ‘boom and bust’ nature of extractive industries on surrounding communities (Dana; Kaufman and Kaufman). Extractive communities’ poverty is attributed to the domination of external actors, specifically: 1) the state/natural resource agency that is a significant holder of rural resources and 2) capital, especially global resource corporations. The external state (bureaucratic power), capital and the national and global economic structure (declining terms of commodity trade and the lack of forward and backward economic linkages in the resource communities) affect resource production and responses within resource-dependent communities (Machlis et al.; Peluso et al.; Freudenberg and Gramling, ‘Linked to What?’). The communities’ geographic isolation also contributes to limited economic opportunities (Randall and Ironside), while the high but intermittent wages encourage people to stay and over-invest or over-specialise in resource extraction. Local community planning and economic development projects have little to no impact on the global and national decision-making environment that affects these communities which remain impoverished, domestic resource-producing colonies (Freudenberg). Preserving environmental amenities may enable the communities to shift to the service sector and decrease poverty in the long-term (Freudenberg and Gramling), but the resource-dependent community (and its employment possibilities) would change from being extractive to non-consumptive (tourism-related) or backdrop-oriented for industrial relocation (Peluso et al.). Tourism may itself lead to another form of export-led dependency (English et al.; Schmallegger and Carson).

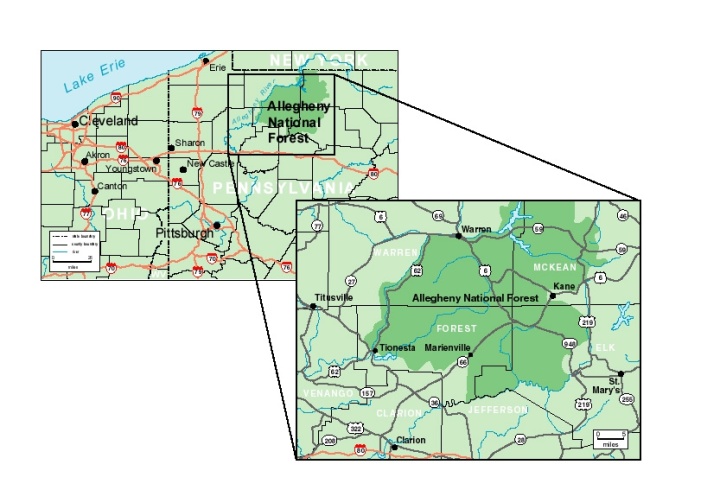

Scholarship about rural change shows how property regimes and resource demands have shaped stages of extraction and tourism development in the Allegheny National Forest (ANF) region in the following ways. Firstly, historical land use production has shaped current landscapes as both Native American and European settlers’ land use has led to forest clearing for timber, agriculture and oil (Williams; Whitney; Black). Secondly, the ecological implications of consumption have been recognised, including how rural resource hinterlands have been shaped by urban demands (Cronon). Thirdly, it has been shown that past resource management and land use policies precondition new rounds of development and policy decisions as changing desires for rural resource use are linked to broader global, national and regional economic shifts and the importance of the consumer becomes paramount.

Resource-driven land acquisition and extraction in Penn’s Woods

Native Americans actively shaped the forests of the Allegheny Plateau. Given the amount of annual precipitation, there was a low incidence of natural fire. Yet the land along the Allegheny River used by Native Americans for thousands of years as travel routes and for habitation have forest types born of fire. Native Americans used fire for warmth and cooking and as a tool in both agricultural and hunting practices. Due to their use of fire, Native American populations had the strongest effect on the growth of oak, hickory and chestnut forest types in the western part of the ANF region. Additionally black walnut is found only in proximity to Native American villages (Black, Ruffner, and Abrams). Thus, like the Aboriginal people in Australia, Native Americans shaped the landscape that European settlers ‘discovered’.

The ‘original’ or pre-European settlement forest found in the ANF region differed greatly from the present one. Hemlock and beech once made up 63 percent of all trees listed in early land surveys of the Allegheny Plateau. The now-abundant, commercially valuable, shade-intolerant black cherry made up only 0.09 percent of the original forest prior to 1820. Oak types associated with Native American settlements and white pine, whose wood initiated the area’s land acquisition and timber harvesting, respectively made up 5.7 and 3 percent of the pre-European settlement forest (Marquis).

Resource-based land acquisition in the Allegheny Plateau favoured industrial extraction of this forest, rather than pioneer settlement. The state of Pennsylvania purchased what is now the north-central and northwestern parts of the state from Native Americans in 1784-1785 (Southwest Pennsylvania Genealogical Services) which greatly reduced the Native

American presence. A Native American settlement on the 1791 Cornplanter Grant that the Pennsylvania General Assembly granted Cornplanter, a chief of the Seneca nation, and his heirs in gratitude for his diplomatic efforts checking the development of a threatening alliance between eastern and Ohio Indians against the settlers remained until 1964 when it was flooded out by the construction of a dam on the Allegheny River (Deardoff). The lands purchased from Native Americans in 1784-1785, known as the Indian Land Cessions, were largely sold in 1792 to large Philadelphia, Dutch and British capitalists who had the financial resources to purchase four million acres of land in 1,000-acre warrants at 13 cents per acre (Ross Northwestern Pennsylvania Timber Industry). Much of this land subsequently ended up in the hands of ‘Yankee’ New England and New York settlers interested in resource extraction and development (Childs History; Groenendaal & Jones Consultants).

Figure 1: The ‘original’ forest: Tionesta Old Growth Area, Allegheny National Forest (Source: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Allegheny National Forest)

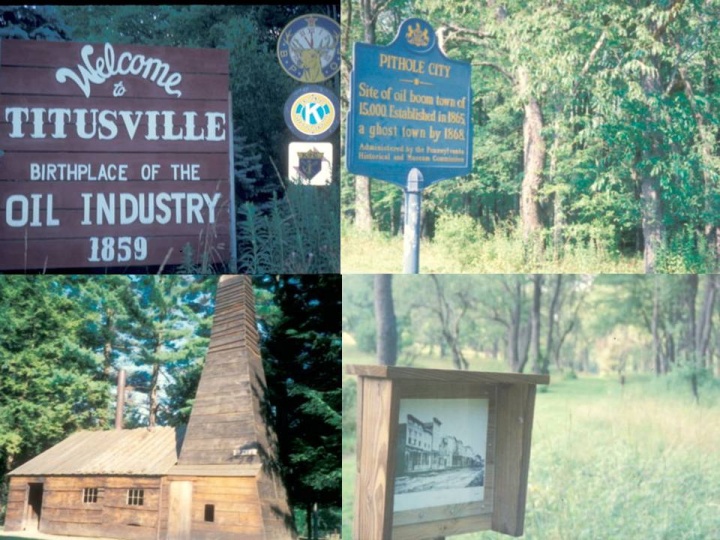

Timber harvesting of the hemlock-beech which dominated the Allegheny Plateau forests (Figure 1) occurred in distinct phases. The initial timber harvesting phase (1800-1830) consisted mainly of early pioneer clearings for cabin construction and agriculture. The water transportation harvesting phase (1830-1890) was dominated by the aforementioned large Yankee timber interests, who acquired large tracts of land and organised lumber companies, and was marked by the select harvesting of white pine from this resource hinterland to feed building construction in downstream Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and New Orleans (Wilhelm). Timber harvesting was also fuelled by the need of the oil and leather industries. Oil, used by Native Americans for medicinal purposes, was commercially discovered in 1859 along the Oil Creek Valley in neighbouring Venango County, the birthplace of the world’s commercial oil industry. Subsequent oil fields which required large quantities of lumber for rig construction were discovered and exploited throughout the ANF region (Casler; Childs History; Ross Allegheny Oil; Black). The capital-intensive, steam-powered, ‘logging railroad’ era (1890-1920) both facilitated and required year-round clearcutting of the remaining pine, hemlock and hardwoods (Marquis) to feed the large-scale sawmills, tanneries and wood chemical plants. As a result, the virgin and partially cut forests of the Allegheny Plateau were almost completely clearcut in what Marquis (11) called ‘the highest degree of forest utilization that the world has ever seen in any commercial lumbering area’. The end of this first stage of industrial resource extraction, lasting from the mid-1800s up until World War I, left behind millions of acres of bare hillsides, ghost towns and depopulated cities and resulted in Penn’s Woods being turned into the Allegheny Brush Pile (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Logged hillside, Pennsylvania (Source: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Allegheny National Forest)

Government acquisition and transition from the ‘Allegheny Brush Pile’ to the ‘Natural Escape’

Following unsustainable resource extraction, the importance of tourism and the role of the state increased as regional and local capital used concerns about deforestation and subsequent flooding in downstream Pittsburgh to push the federal government to acquire the cutover lands. Local business interests, many of whom were large landholders and/or involved in timber-related businesses, supported the creation of the ANF in 1923 as the federal government would also be a willing buyer for deforested private timber lands that might not be attractive to short-term private investors. Only surface rights, not mineral rights, were acquired since the government could only buy land for less than US$4.00/acre (US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Allegheny National Forest). This resulted in a split estate akin to that in Australia although with private subsurface owners and public surface owners on the Allegheny. The past private ownership and liquidation of timber stands led to state ownership of almost 50 percent of Forest County, one of the ANF counties (Figure 3). The local business elite believed that the ANF would reforest the acreage, develop recreational resources (such as campgrounds and reservoirs) and improve roads to, from and within this isolated part of northwestern Pennsylvania, thus making ‘a hunting, fishing and recreation ground amidst beautiful scenery, cool climate and gorgeous vistas, within easy reach of the great business centers’ of Pennsylvania and neighbouring states (Allegheny Highway Association). The state thus replaced capital as the dominant actor that would fuel development of this resource-dependent area.

State management fostered both resource extraction and tourism and the transformation of the ‘Allegheny Brush Pile’ to the ‘Natural Escape’.While ANF commercial timber harvests largely did not resume until 1960, the regenerating forest created ideal conditions for deer, cementing the region’s reputation for deer hunting. The ANF’s 500,000 once-deforested acres, which grew to provide quality, public-access deer hunting, drew deer-poor residents of urban and industrial western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. Production-oriented Forest Service policies that supplied timber for post-war suburban development also increased forest edges resulting in cover and browse favoured by game species (Alverson et al.), thus satisfying the multiple use management mandate for the national forests. In the pre- and post-World War II era, visitors from the region’s industrial cities such as Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Buffalo built hunting camps and seasonal homes on private tracts surrounding the national forest. One prominent developer, Ernie Matson, who first came to Forest County in 1923 from industrial New Castle, Pennsylvania, as a deer hunter, opened 13 areas for campers in the 1950s and 1960s, the largest of which contained over 4.5 miles of road and over 500 lots on 380 acres (Figure 4) (‘Ernie Matson’). Additionally, historical sites tied to the ongoing extractive industries were viewed increasingly as heritage tourism resources (Black; Fermata). In the case of oil heritage, such sites included the Drake Well, the first commercial oil well in the US, as well as the ghost town of Pithole (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Oil Heritage Sites (clockwise from top left: Welcome to Titusville, Pithole City sign, Pithole today, Drake Well Engine House in Titusville) (photos by author)

Yet job opportunities were limited for the year-round residents of this natural escape, given local and regional deindustrialization which impacted manufacturing and tourism. One ANF county, Forest, was eligible for US Department of Agriculture Forest Service (USFS) Economic Recovery funding for economically disadvantaged, forest-dependent, non-metropolitan local governments or counties which emphasised marketing, training and advice as well as entrepreneurship based on localised resources and enterprise (US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Economic Action Program). Forest County had the resource-dependency paradox of valuable resources, and one of Pennsylvania’s lowest median household incomes and its highest unemployment rate. County economic diversification projects funded by the USFS program included tourism-focused studies to assess the feasibility of developing (1) a tourist cabin/camp rental business that would use some of the 5,000 existing private camps/cabins that were only used by their owners for short periods during the year, (2) a Hunting and Fishing Museum and (3) ecotourism (Che ‘The New Economy’).

Demands on the ‘land of many uses’

Past clearcutting of the old- and second-growth hemlock-beech dominated forest produced the spatially unique Allegheny hardwoods forest which has a higher commercial value today than the remaining old-growth stands due to the prevalence of veneer-quality black cherry (which thrived under the open conditions) (Whitney). As a result of harvesting this mature black cherry, up until 1997 the ANF’s production of 80 percent of the world’s black cherry sawtimber and veneer used in fine furniture (Figure 6) led to its being the highest earning US national forest. Harvesting generated 99 percent of ANF gross receipts, with 25 percent going in lieu of taxes to the four counties with ANF lands. From 1987-1997, the ANF counties received a total of US$48.7 million, or an annual US$4.42 million average, for much needed school and road funding (US Department of Agriculture, ANF Fact).

However, only a limited number of jobs were generated as the valuable hardwoods were largely shipped out as raw logs. The ANF region and in particular the smallest ANF county, Forest, had limited value-added facilities. Also, local producers were outbid for the highest-value logs by fine furniture manufacturers in Italy and Germany, or by US furniture manufacturers in North Carolina. Akin to Australian resource-dependent towns in which minerals did not stimulate manufacturing but were exported to the highest bidders, veneer-quality hardwoods left the region with little or no value-adding. In an attempt to rectify this situation, the USFS funded a waste wood recycling project to locate Black Cherry tree crotches that were not currently saleable overseas due to size or defects, process them into usable blanks and then lathe/reprocess them to create unusual products such as upscale, large wooden bowls or wooden fishing plugs (Figure 6). The aim was to develop a business based on manufacturing unique wooden bowls (Forest County Action Team).

Figure 6: Black Cherry (clockwise from top left: Allegheny Hardwood forest including mature black cherry with its distinctive broken dark gray to black bark, fine furniture utilizing veneer-quality black cherry, black cherry bowls) (Top photos by US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Allegheny National Forest; bottom photos by author)

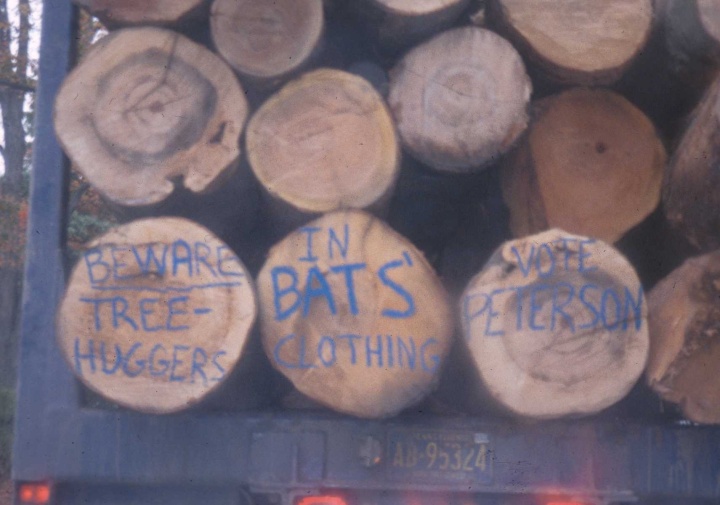

However, resource extraction has increasingly been in conflict with tourism and growing local and regional environmental concerns. While if not in the numbers of the post-World War II period, the orange army of hunters still arrives at the beginning of deer season. Non-consumptive tourism however is growing in relative importance as new visitors have diversified interests including hiking, canoeing, biking, ATVing, and horseback riding. Litigation first brought in 1997 by the Allegheny Defense Project (ADP), an environmental activist organization which advocated a ‘zero cut’ policy on public lands, dramatically reduced harvests. That year the ADP filed the first lawsuit against the forest and successfully halted Mortality II, a reforestation project developed in response to the deaths of insect-defoliated trees. Mortality II included seedling plantings, herbiciding, overstory thinning, erecting deer-proof fencing and tree harvesting on 18 tracts on more than 5,000 acres (Steiner and Steiner). The ADP won the case on procedural grounds that an environmental impact statement, not the less comprehensive environmental assessment, should have been performed (Hopey). Mortality II did not consider the cumulative effect of extraction across multiple tracts, which omission is akin to Australian mineral extractors’ not taking into account the effect of multiple projects. Timber harvests fell dramatically again as a moratorium on harvesting occurred from late 1998–1999 due to the capture of a live, endangered Indiana bat (Figure 7).

Different conceptions of the forest, community, and Native Americans

Timber harvesting resumed shortly afterwards. But the timber conflict, which was rooted in different views of community, the ideal forest, and Native Americans held by environmentalists and local communities tied to resource extraction, continued. While ‘dedicated to finding community-based solutions for restoring the ecological integrity of the region and building sustainable economies benefiting the health of all forest communities of the Allegheny National Forest’, the ADP’s proposition of tourism as ‘a replacement rather than a supplement to logging’ (italicised by author) would alter many lives, particularly those involved in resource extraction (Guilyard 1996). Although few Native Americans lived in the ANF region—hence the lack of an Indigenous perspective—the ADP’s concept of community would encompass them. The organization’s long term goals included building a coalition with Indigenous peoples ‘based on their respect for the earth’(Allegheny Defense Project). The ADP view echoes the popular signification of Indigenous Australians as a ‘simple, timeless, ecologically sustainable society’ (the eco-angel myth). Waitt, in his use of Barthes’ framework for analysing myths, argues this and other significations of Indigenous peoples make their portrayal as ‘primitive’ an effective marketing tool underpinning the Australian Tourist Commission’s (now Tourism Australia) international advertising strategies. For the ADP the desired forest was the native, pre-European settlement forest with ‘symbolic species’ such as the grey wolf, bison and mountain lion. These would need to be reintroduced since no viable populations of those animals were near enough to the ANF to naturally migrate there. The ADP has a ‘set-aside’ approach, which advocates protection/no logging and leaving nature to manage itself (which Native Americans did not do). This approach will not, however, support the maintainenance of eastern old-growth in the ANF, which probably most closely approximates the native forest. In the ANF’s Tionesta Research Area, which had never been clearcut, old-growth hemlock has declined over the past 60 years from 63 percent to only 45 percent or less of the canopy (Center for Rural Pennsylvania Pennsylvania Ecotourism).

Forest-dependent Forest County also connected with Native Americans. Forest County has long utilized this link as part of its tourist appeal. The Tionesta Indian Festival was its largest event, attracting 20,000 people to its 500+ person county seat. Started initially in 1963 by the West Forest Business Corporation, the event aimed ‘to promote a festive atmosphere and provide eight days of fun for both Forest County residents and visitors’ by using an Indian theme, as its original inhabitants were the Seneca Indians (Munsee tribe). The festival initially featured an Indian princess contest, mock battle between settlers and Indians, and games and events for teens (Childs ‘Tionesta Area’). Local and seasonal residents were participants, not Native Americans. Under the leadership of a white Tionesta resident, Jack McMichael, it incorporated more Native content. McMichael who wanted to learn more about the Seneca was eventually adopted by the tribe1 (‘McMichael Adopted by Seneca Indians’). His clan sister, Thelma Shane who had long been selling Indian Ghost Bread at the festival, said that although some Seneca Indians do not appreciate being imitated, she found it ‘a compliment to my race that other people want to be Indian. They put in a lot of time and effort into trying to be authentic and they do it with respect for the Indian’ (‘McMichael Adopted by Turtle Clan’). Although participants remain largely non-Indigenous Forest County residents, there have been presentations by Seneca Indian dancers (Figure 8). Ultimately, the Tionesta Indian Festival is a small town event which raises significant funds from tourists for non-profit community organizations.

Figure 8: Tionesta Indian Festival (clockwise from top left: Tionesta Indian Festival parade, Princess and Brave float, Seneca Indian Dancers, Tepee and Brave float bowls) (photos by author)

However, on the resource conflict issue, this connection with Native Americans played out differently in conceptions of the community and forest. The chairman of the Forest County Action Team, a group of local citizens who organised to access USFS funds for economic diversification projects, wearing his hat as Forest County Conservation and Planning District director wrote in his weekly column of the shutting down of Mortality II by the ADP, supposedly to help local citizens and the forest:

What we face is the same kind of blackness the Native American did, when they first said to themselves (as the pilgrims pulled up) ‘There goes the neighborhood’. Our neighborhood is being overrun by green uniforms, green camo fatigues, and green ideas, which derive from pagan philosophy rather than modern reality. Real stewardship begins with an investment of a life. Lots of the citizens of Forest County have made the life investment, they are stewards of the land, good stewards already! (Carlson, ‘Conservation’3).

A connection was also made between the current local resource management and use and that of Native Americans. Locals are following in the footsteps of Indigenous peoples, ‘who did not set aside land but managed it wisely, beginning with fire for hunting, both to draw game with new growth following fire and to drive game towards hunters, and for agriculture to clear the ground’ (Carlson, ‘Pristine Wilderness’ 9), thus resulting in the aforementioned oak stands. According to Carlson, the Native American was:

… NOT an environmentalist or any number of the modern day off-shoots of environmentalism. The Indian used nature and what the earth provided. He did not protect it nor did the Indian destroy it. To protect is to save and not use. To destroy is to disrespect and act in an ignorant or selfish manner. The Amerindians did not view the earth in either way…. Conservation IS the WISE USE of natural resources. The first conservationists in America were the Indian people. (‘Doin’ the Indian’ 17, capitalised in the original)

However, identifying with Native Americans and recognizing their conservation practices did not mean going back to the myth of the primitive past-tense noble savage or the pre-European settlement forest envisioned by the ADP. Carlson writes, ‘Where do we go from here? Like my brother says, “Hey, this is our country now, we stole it fair and square!” Another more famous person put it in another far better way, “You can’t go home again.” Instead of looking back, we need to look at the future’ (Carlson, Pristine Wilderness). The future to the local community reliant on resource extraction would involve continual harvesting and reproduction of black cherry, a valuable pioneer species, and not allowing the forest to be eventually dominated by climax species.

Continued resource conflicts in ‘Pennsylvania Wilds’

However despite these conflicts, timber production constrained more by the GFC and the US housing downturn may be more compatible with tourism than other forms of resource extraction. The ANF region, along with much of the Northern Tier of Pennsylvania, has been branded and marketed for outdoor recreation and heritage tourism as Pennsylvania Wilds, a 12-county region containing hundreds of miles of land and water trails and the largest block of public land between New York City and Chicago. The Pennsylvania Wilds recreation plan which recognised the region’s hardwood forests and forest products industry would also implement the interpretive plan of the Lumber Heritage Region (within the Pennsylvania Wilds region) (Fermata Inc., ‘Lumber’; Fermata Inc., ‘Recreation’).

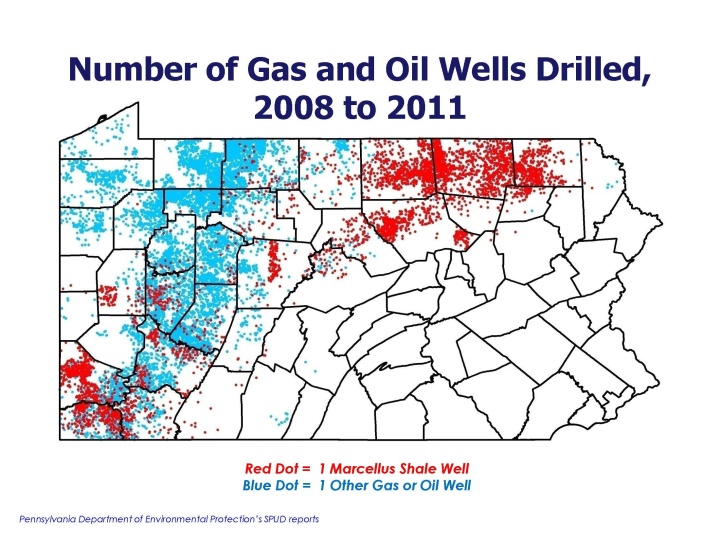

By comparison, expanded oil and gas production over which there is less regulation due to the split estate on the ANF may lead to greater environmental conflicts and conflicts between resource extraction and nature-based tourism and recreation. While the ANF is in the middle of the Marcellus Shale region which is, given the technological advance of hydraulic fracking, seen as the newest frontier of natural gas production in the US, most of the oil and gas wells drilled to take advantage of rising oil prices have been the traditional shallow ones (Center for Rural Pennsylvania) (see Figure 9). Organizations representing private oil and gas interests which own the subsurface rights have sued the ANF over its management plan. They have opposed the ANF’s intention to undertake NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) analysis to protect surface resources, including those for tourism and wildlife, prior to issuing notices for oil and gas development on the forest. In order to proceed, according to the Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Association and Allegheny Forest Alliance, Forest Service notices need to restrict access to subsurface mineral rights, a right the agency does not have as they claim it is required by law to ‘accommodate oil and gas development on lands with privately owned OGM (oil, gas, and mineral) rights’ (Ferry, ‘Lawsuit’). Subsequently, a judge has issued an injunction preventing the Forest Service from halting new drilling on the national forest until environmental impact assessments can be performed (Schellhammer). The US Department of the Interior (DOI) has proposed new oil and gas drilling rules which would require companies to publicly disclose the chemicals they use in hydraulic fracturing on the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) managed mineral estate which includes 700 million subsurface acres of federal estate and 56 million subsurface acres of Indian mineral estate.2 As over 93 percent of the ANF subsurface is privately held, only drilling on the less than seven percent federal estate would be subject to these rules (Ferry, ‘Fracking Rule’). To address the problem with the split estate, another environmental organization, Friends of Allegheny Wilderness, is driving an effort to purchase the subsurface mineral rights under 5,200 acres in a proposed wilderness area in the ANF, but such rights would cost an estimated US$1,000-2,000 per acre (Wells). The legacy of the split estate on the ANF will have a lasting impact on surface land uses including tourism.

Summary and concluding remarks

On the Allegheny Plateau, past human use has reshaped the land and established the property regimes and conditions for future land uses. Resource-based land acquisition in the Allegheny Plateau favored industrial extraction, a consumption linkage between urban and rural ecosystems. Although the almost complete clearcutting and historic oil extraction of the Allegheny Plateau left behind millions of acres of bare hillsides, ghost towns, and polluted waterways, a new forest seemingly miraculously arose from the ‘Allegheny Brush Pile’. Past private ownership and liquidation of timber stands led to the state, in the form of the US Department of Agriculture Forest Service and ANF, replacing capital as the largest landholder in Forest County, Pennsylvania. The ANF, like other national forests, was legislatively required to manage the land for favorable water flows, provide continuous timber supplies for the nation, stabilise forest-dependent communities and, later, manage the land for other multiple uses including outdoor recreation and wildlife. The state used federal reforestation, highway and flood control programs to establish the timber and recreational resources (campsites, reservoirs, deer habitat) which attracted those from industrial cities and fueled post-World War II seasonal home development on adjacent private lands.

However, resource extraction and tourism have increasingly been viewed as conflicting, not complementary uses. More recently, harvesting of the mature Allegheny hardwoods, which replaced the ‘original’ hemlock-beech dominated forest, has initiated battles over land use. Such battles are rooted in different views of the desired forest. For resource-dependent communities, a forest dominated by pioneer species like black cherry that reproduce under the open conditions produced by logging is ideal, while environmental activists like the ADP wish for the pre-European settlement forest dominated by climax species. In these land use battles, largely non-present Indigenous peoples have alternately been symbolically envisioned as respecting the earth through preservation or as wise users of resources. Yet timber production may be more compatible with tourism than other forms of resource extraction when policy and management frameworks are in place. Branding the Northern Tier of Pennsylvania as ‘Pennsylvania Wilds’ recognises the present hardwood forests, currently managed harvests on public and private lands, and the hardwoods industry as well as its lumber heritage. While historic resource booms are evidenced in the Victorian mansions, theatres, churches and municipal buildings built with oil and timber wealth in towns and cities throughout the region, current oil and gas extraction may pose the greater threat to tourism. As the state acquired only the surface rights, not the mineral rights, of cutover timber lands in the 1920s to create the ANF, regulating extraction of private subsurface resources which impacts the public surface ones is constrained by the split estate.

Historical analysis of shifting, sometimes conflicting, land uses that have shaped and been shaped by property regimes in the ANF region can inform decisions regarding resource extraction that are being faced in Australia, with its split estate scenarios and regional resource dependency. In the ANF case, costs largely preclude purchasing expensive private subsurface rights other than under particularly treasured proposed wilderness areas. In Australia, where the state owns the subsurface, similarly rare National Heritage rulings in mineral-rich areas may be one of the few ways to preserve Aboriginal heritage.

In the likely situations where resource extraction will occur, issues regarding management and regulation of resource extraction as well as questions about who benefits from extraction must be addressed. As previously noted, US counties with national forest lands have received 25 percent of the relevant national forest’s gross receipts in lieu of taxes for schools and roads. Given the variability of timber harvests, the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 (SRS Act) was passed to stabilise funding as well as fund investments in projects that enhance forest ecosystems and improve cooperative relationships. Under the amended SRS Act (2008), these counties can accept either a newly modified 25 percent seven year rolling average payment of receipts from national forest lands or a share of the individual state payment calculated with a formula using multiple factors, which include acreage of federal land within an eligible county, the average three highest 25-percent payments and an income adjustment based on the per capita personal income for each county (US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service). The latter option to some degree decouples payments from the harvests. The SRS funding recognises the impact of federal government lands and resource extraction on local communities. Of real concern is how Australia’s minerals, which are owned by the Crown (in the right of the state), will be managed for the greater national benefit and for local communities. The state has not maximised the national benefits from these publicly-owned resources, offering tax breaks and often selling the resources off cheaply to corporations. While the state provides local communities with services, they do not necessarily compensate for impacts, particularly those from fly-in, fly-out mining (see Carrington et al. in this issue of Australian Humanities Review). Policy and legal frameworks need to be developed so that surface owners and surrounding communities accrue benefits from mining, akin to the percentage of receipts in SRS funding, not just the costs.

Past and current extraction shapes possibilities for future land use and can impact the quality of life. Under ANF administration, the state turned the ‘Allegheny Brush Pile’ into a ‘Natural Escape’. Following regeneration, timber harvesting did not follow the earlier ‘cut-and-run’ practices of the pre-ANF, industrial harvesting era. The quality of life has in part derived from over 500,000 acres of public land that has attracted tourists as well as tourism and value added manufacturing entrepreneurs to the ANF region. Past high manufacturing and extraction wages in paternalistic, dominant resource and manufacturing industries created disincentives for entrepreneurship and educational attainment. Accordingly, amenity-based development may depend on amenity migrants who can help overcome pervasive pessimistic feelings held by long-term residents of resource-dependent areas that new economic development activities won’t work. Many of Forest County’s current entrepreneurs in tourist-oriented businesses (outfitters and sporting goods retailers, for example) are urban in-migrants who first came to the area as tourists and seasonal residents and have decided to live and raise their children there. Similarly the business location decisions of Pennsylvania’s small-scale, value-added hardwood manufacturers ranked an area’s lifestyle, community attitude towards industry, and personal ties (that is whether people previously resided in or had family connections to the area), as more important than traditional economic factors (such as tax and regulatory considerations, infrastructure, services and utilities) (Bodenman et al.; Bodenman). While state and privately managed timber harvesting has coexisted with recreational land uses on the ANF, this coexistence may be more difficult to achieve with oil and gas drilling there, or with mining in Australia. In Australia, mining threatens both the environment and Indigenous culture, significant bases of different types of tourism (see Wergin and Muecke’s introduction to this issue). It is critical to protect Indigenous cultural capital, which is invaluable, truly unique to Australia, integral to its branding, a differentiating draw for international tourists (Franklin; Muecke; Waitt) and a contributor to the quality of life which can support local economic development.

At the same time, while preserving environmental and cultural amenities and capturing benefits from extraction can enable communities to shift to the service sector and decrease poverty in the long term, tourism itself may lead to another form of export-led dependency. Like tourism in remote Australia, tourism in Forest County was impacted by external fluctuations. However, unlike that in the ANF region, tourism in remote Australia is dominated by large external players focused on external mass markets, which is in part due to government policies. In Yulara outside Uluru, the Northern Territory government replaced competing accommodation operators with a single one to maximise its return on investment and grow tourism most rapidly (Schmallegger and Carson). As a result, many Aboriginal-owned, small-scale cultural tourist enterprises are not able to access the international market (Waitt). Such resource-dependent places in Australia could, like those in the US, benefit from planning, if sustained, decentralised marketing assistance; training and advice are provided by the government that would aim to increase local involvement in tourism. As Altman argues, there needs to a better understanding of Indigenous customary activity, and whether Indigenous peoples are producing for their own use or for commercial exchange such as in tourist encounters. But, as he notes, state institutions could be redesigned to better support their efforts. Planning could involve State guidance of Indigenous development as it has done for non-Indigenous people in remote Australia. On-going assistance to build local resources and linkages could encourage local amenity-based business development and help Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities to escape the treadmill of resource dependency, as it is shaped by property regimes and historic land uses.

Deborah Che is a Lecturer in the School of Tourism and Hospitality Management and a researcher in the Centre for Tourism, Leisure, and Work at Southern Cross University. Her research interests include rural and community development, natural resource-based tourism (i.e., agritourism, ecotourism, hunting) development and marketing, cultural/heritage tourism, and arts-based economic diversification strategies. A common theme in her extensive rural and small town research involves the interconnection between economic restructuring and shifting land uses. She has published in geography, tourism, and social science journals including Geoforum, The Annals of the Association of American Geographers, The Professional Geographer, Tourism Geographies, Journal of Heritage Tourism, Tourism Recreation Research, Tourism Review International, Social Science Quarterly, and Agriculture and Human Values. She is on the editorial board of Tourism Geographies and has served as Chair of the Recreation, Tourism, and Sport specialty group of the Association of American Geographers.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Carsten Wergin, Stephen Muecke and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript, which clarified and strengthened this article. I am particularly grateful to Carsten Wergin, who provided comments, guidance, encouragement and support throughout the publication process. I would also like to thank the Center for Rural Pennsylvania and the Allegheny National Forest for permission to use their images. Thanks also to Anne Gibson for cartographic assistance.

Notes

1 Such adoptions are not likely to occur in the future as tribal membership disputes and disenrollment have escalated nationwide, in large part due to the division of casino profits and bonuses as well as health insurance, educational scholarships, and other benefits among tribal members (Dao).

2 The Indian mineral estate refers to the 57 million acres of subsurface minerals estates that are held in trust by the United States for American Indians, Indian tribes, and Alaska Natives and that are administered and managed by the US Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), an agency of the US Department of the Interior. The BIA also manages 55 million surface acres of Native lands. Native Americans have sued the BIA and US Department of the Interior over billions of dollars missing and unaccounted for in the Indian Trust Fund.

Works Cited

Allegheny Defense Project. ‘Allegheny Defense Project.’ 18 Nov 1996. http://www.alleghenydefense.org Accessed 2 Dec. 2012.

‘Allegheny Highway Association.’ Forest Republican, 1 February 1922:4.

Altman, Jon C. ‘Economic development and Indigenous Australia: Contestations over Property, Institutions and Ideology.’ The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 48.3 (2004): 513-34.

Alverson, William Surprison, Walter Kuhlmann and Donald M. Waller. Wild Forests: Conservation Biology and Public Policy. Washington: Island Press, 1994.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. London: Jonathon Cape, 1972.

Black, Brian. Petrolia: The Landscape of America’s First Oil Boom. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 2000.

Black, Bryan A., Charles M. Ruffner and Marc D. Abrams. ‘Native American Influences on the Forest Composition of the Allegheny Plateau, Northwest Pennsylvania.’ Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36.5 (2006): 1266-75.

Bodenman, John E. ‘Analysis of Hardwood Manufacturers Location Decisions: Northern and Central Appalachian States, 1989-1999.’ Middle States Geographer 35 (2002): 76-85.

—, Stephen M. Smith and Stephen B. Jones. ‘Do Manufacturers Search for a Location? The Case of Hardwood Processors.’ Journal of the Community Development Society 27 (1996): 113-29.

Carlson, Douglas E. ‘Conservation District Notes: Doin’ the Indian!’ Forest Press, 6 August 1997: 17.

—. ‘Conservation District Notes: Pristine Wilderness: The maculate assumption!’ Forest Press, 27 September 1995: 9.

—. ‘Conservation District Notes: Thanks a lot!’ Forest Press, 3 December 1997: 3.

Casler, Walter C. Tionesta Valley. Williamsport, PA: Lycoming Printing Co., Inc., 1973.

Center for Rural Pennsylvania. Map: Number of Gas and Oil Wells Drilled, 2008 to 2011. Unpublished document. Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 2012. 625 Forster Street, Room 902, Harrisburg, PA 17120, USA. http://www.rural.palegislature.us Accessed 2 Dec. 2012.

—. Pennsylvania Ecotourism: Untapped Potential. Harrisburg, PA: Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 1995.

Che, Deborah. ‘The New Economy and the Forest: Rural Development in the Post-Industrial Spaces of the Rural Alleghenies.’ Social Science Quarterly 84.4 (2003): 963-78.

Childs, Ronald. History of Forest County 1867-1967. Tionesta: Forest Press, Inc., 1989.

—. ‘Tionesta Area Indian Festival.’ Forest Press,22 August 1984: 6.

Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1991.

Dana, Samuel Trask. Forestry and Community Development. US Department of Agriculture Bulletin 638. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, 1918.

Dao, James. ‘In California, Indian Tribes With Casino Money Cast Off Members.’ New York Times, 12 December 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/13/us/california-indian-tribes-eject-thousands-of-members.html. Accessed 2 Dec. 2012.

Deardoff, Merle H. Chief Cornplanter. Historic Pennsylvania Leaflet No. 32. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1972.

English, Donald B. K., David W. Marcouiller and H. Ken Cordell. ‘Tourism Dependence in Rural America: Estimates and Effects.’ Society & Natural Resources 13 (2000): 185-202.

‘Ernie Matson.’ Forest Press, 9 February 1967: 8.

Fermata, Inc. Lumber Heritage Region’s Interpretive Plan. Austin, TX: Fermata, Inc., 2005.

—. A Recreation Plan for the State Parks and State Forests in the Pennsylvania Wilds. Austin, TX: Fermata, Inc., 2006.

Ferry, Brian. ‘Fracking rule affects tiny part of ANF.’ Times Observer, 8 May 2012. http://timesobserver.com/page/content.detail/id/557357/Fracking-rule-affects-tiny-part-of-ANF.html. Accessed 8 May 2012.

—. ‘Lawsuit, Litigants Unsettled.’ Times Observer, 11 April 2009. http://timesobserver.com/page/content.detail/id/515034.html. Accessed 11 Apr. 2009.

Forest County Action Team. Proposal for Wood Waste Recycling Pilot Project. Tionesta, PA: Forest County Action Team, 1997.

Franklin, Adrian. ‘Aboriginalia: Souvenir Wares and the “Aboriginalization” of Australian Identity.’ Tourist Studies 10.3 (2010): 195-208.

Freudenberg, William R. ‘Addictive Economies: Extractive Industries and Vulnerable Localities in a Changing World Economy.’ Rural Sociology 57.3 (1992): 305-22.

—, and Robert Gramling. ‘Natural Resources and Rural Poverty: A Closer Look.’ Society and Natural Resources 7 (1994): 5-22.

—. ‘Linked to What? Economic Linkages in an Extractive Economy.’ Society and Natural Resources 11 (1998): 569-86.

Groenendaal & Jones Consultants. Lumber Heritage Region Feasibility Study (draft), Groenendaal & Jones, Easton, PA, 1997.

Hopey, Don. ‘Judge Halts Big Tree Sale, Orders Study.’ 18 Oct 1997. Envirolink. http://www.envirolink.org/orgs/adp/archive/m2winhopey.html. Accessed 2 Dec. 2012.

Kaufman, Harold Frederick and Lois C. Kaufman. ‘Toward the Stabilization and Enrichment of a Forest Community.’ Community and Forestry: Continuities in the Sociology of Natural Resources. Eds. Robert G. Lee, Donald R. Field and William R. Burch, Jr. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1990. 27-52.

Machlis, Gary E., Jo Ellen Force and Randy Guy Balice. ‘Timber, Minerals, and Social Change: An Exploratory Test of Two Resource-Dependent Communities.’ Rural Sociology 55.3 (1990): 411-24.

Marquis, David A. The Allegheny Hardwood Forests of Pennsylvania. Upper Darby, PA: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, 1975.

‘McMichael Adopted by Seneca Indians.’ Forest Press 6 August 1975: 1.

‘McMichael Adopted by Turtle Clan.’ Forest Press 21 August 1985: 1.

Muecke, Stephen. Opening remarks at ‘Songlines vs. Pipelines? Mining and Tourism Industries in Remote Australia.’ University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, 28-29 February 2012.

Peluso, Nancy Lee, Craig R. Humphrey and Louise P. Fortmann. ‘The Rock, the Beach, and the Tidal Pool: People and Poverty in Natural Resource-Dependent Areas.’ Society and Natural Resources 7 (1994): 23-38.

Randall, James E. and R. Geoff Ironside. ‘Communities on the Edge: An Economic Geography of Resource-Dependent Communities in Canada.’ Canadian Geographer 40.1 (1996): 17-35.

Ross, Philip W. Allegheny Oil: The Historic Petroleum Industry on the Allegheny National Forest. Morgantown: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Eastern Region and West Virginia University, Institute for the History of Technology and Industrial Archaeology, 1996.

—. The Northwestern Pennsylvania Timber Industry. Forthcoming.

Schellhammer, Marcie. ‘Possible Resolution Pending in ANF Mineral Rights Case.’ Times Observer, 4 February 2012. http://timesobserver.com/page/content.detail/id/555498/Possible-resolution-pending-in-ANF-mineral-rights-case.html. Accessed 4 Feb 2012.

Schmallegger, Doris and Dean Carson. ‘Is Tourism Just Another Staple? A New Perspective on Tourism in Remote Regions.’ Current Issues in Tourism 13.3 (2010): 201-21.

Southwest Pennsylvania Genealogical Services. Pennsylvania Line: A Research Guide to Pennsylvania Genealogy and Local History. 4th ed. Laughlintown, PA: Southwest Pennsylvania Genealogical Services, 1989.

Steiner, Bob and Linda Steiner. ‘Court’s Decision Could Decide Hunting’s Future.’ The Derrick, 8 January 1998: 12.

US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Allegheny National Forest. ANF Fact Sheet. Warren, PA: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Allegheny National Forest, 1998.

US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Economic Action Program. Economic Recovery Program Participation and Eligibility Guidelines. 1995.

US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. ‘Secure Rural Schools Program, 2008-2011.’ http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5102926.pdf. Accessed 5 Mar 2009.

Waitt, Gordon. ‘Naturalizing the “Primitive”: A Critique of Marketing Australia’s Indigenous Peoples as “Hunter-gatherers”.’ Tourism Geographies 1.2 (1999): 142-63.

Wells, Dean. ‘OGMs in Proposed Wilderness Sought: Group Hopes Rights Will Be Donated.’ Times Observer, 18 June 2008. http://timesobserver.com/page/content.detail/id/502387.html. Accessed 2 Dec. 2012.

Whitney, Gordon G. From Coastal Wilderness to Fruited Plain: A History of Environmental Change in Temperate North America, 1500 to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1994.

Wilhelm, Samuel Alfred. ‘History of the Lumber Industry of the Upper Allegheny River Basin during the Nineteenth Century.’ PhD Diss. University of Pittsburgh, 1953.

Williams, Michael. Americans and Their Forests: A Historical Geography. Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 1989.