By Ann Rigney

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version.

On Sunday 30 January 1972, on the occasion of a civil rights demonstration calling for greater equality for the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland, members of the British army started shooting into the crowd, killing 13 innocent civilians (a 14th died later of his wounds).[1] This atrocity has come to be known as ‘Bloody Sunday’ and is generally considered to have been a turning point in the Troubles that marked a swing towards paramilitary violence. In the course of the last forty years, Bloody Sunday has time and again been mediated and remediated (Erll and Rigney) across a range of genres and platforms. It has been depicted in literature, theatre, cinema, music, murals, monuments, and evoked through iconic photographs (Herron and Lynch).[2] It has been annually commemorated in the streets of Derry (Conway). It has been the subject of two major judicial inquiries, one of which (the Widgery report of 1972) exonerated the army of all blame, while the other (the Saville report of 2010) acknowledged almost four decades later that its actions were ‘unjustified and unjustifiable’, an admission of culpability that led to an official apology on the part of the British Prime Minister (Rigney). In short: Bloody Sunday has become a central ‘site of memory’ (Nora) for the nationalist community across the island of Ireland. Thanks to the many representations mentioned above, the name stands for a singular, site-specific event, with an enormous local impact, but also for the long-term struggle of the nationalist-Catholic minority in Northern Ireland or, even more generally, for the long-term struggle for national sovereignty in Ireland as a whole. It is usually within a national framework that its significance and impact has been studied (Hayes and Campbell; Herron and Lynch; Dawson; Conway).

Figure 1: Mural in Derry, remediating iconic photograph of Bloody Sunday 1972; Photograph Timothy J. Barron (2010); reproduced with permission

What has received less attention, however, is the fact that the memory of this highly-localised event has also ‘travelled’ (Erll) across national borders with the help of the news media and the arts (the U2 song ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ (1983) and the movie Bloody Sunday (2002) by Paul Greengrass being of particular importance in this regard). The fact that there are Wikipedia articles in no fewer than 42 languages is testimony to the transnational reach of its impact. While being a central site in local, regional, and national memory across Ireland, Bloody Sunday has also come to figure in the cultural memory of groups elsewhere and become connected to other histories. The mere fact that Bloody Sunday has ‘travelled’ in this way indicates that some memories have a greater geopolitical reach than others, and that events at different locations can become connected as part of a larger transnational dynamics of remembrance. But what gives some local events a greater transnational resonance than others? That will be my central concern here.

As I have argued elsewhere (De Cesari and Rigney), transnationalism as an analytic perspective involves a ‘multiscalar’ approach that acknowledges the interplay between the intimate and familial, the local, the national and the transnational, without privileging any one scale as the locus for the production of cultural memory. In setting out to explore from a multiscalar perspective how events in Derry on 30 January 1972 resonated with events elsewhere (in Northern Ireland, in Ireland, in Britain, in Europe, and beyond), I do not wish to deny the intense importance of Bloody Sunday to the victims’ families and the local community in Derry; nor to deny the importance of the Irish national framework, since this has clearly played a huge role in the public interpretation of the atrocity. However, in line with other critiques of methodological nationalism, my analysis does challenge the national framework as the exclusive determinant of any collective meaning that is broader than the local. It does so in order to understand better how the sharing and ‘articulation’ of memory (De Cesari and Rigney) also occurs along lines that transcend and sometimes challenge national borders.

The Differential Distribution of Memorability

Elsewhere I have described how memory sites come into being, arguing that the cultural production of memory sites is governed by the principle of scarcity (Rigney ‘Plenitude’). It is by virtue of selection and recursivity that common points of reference can emerge, since if all details were retained sharing would become impossible. This means that particular events, and particular figures, details, or moments within those events, must become the focus of disproportionate attention, and be recollected time and again, while others are sidelined. What Judith Butler has called ‘the differential distribution of public grieving’ with reference to media representations of contemporary wars (Butler 38) would thus also seem to be a structural, if hitherto insufficiently recognised principle in public remembrance. Whatever the underlying principles of selection may be, it appears that cultural memory is the outcome of a fundamentally non-egalitarian process, which I propose to call ‘differential memorability’. The sharing and elaboration of collectively significant stories works in tension with the respect for the singularity of each victim’s story which underpins discussions of historical justice and memory, where the individual witness and individual victim are taken as the privileged unit of analysis.

That public grieving is distributed unevenly becomes evident when the salience of Bloody Sunday, and with it that of the 14 victims whose names and faces have figured in so many mediations, are compared to the relative obscurity of another event that took place some six months earlier. Over a three-day period in August 1971, 11 Catholics going about their daily business in the Ballymurphy area of Belfast were killed in drive-by shootings by members of the British army. Although the number of individual victims is comparable, the ‘Ballymurphy Massacre’ as an aggregate event is much less prominent in cultural memory at home and abroad than Bloody Sunday. It has generated very little media attention outside the local community: so far there are Wikipedia articles about Ballymurphy in four languages only, including English, and no television drama or movie, though recently it has been the subject of an award-winning documentary (The Ballymurphy Massacre). Crucially, it has not been the subject of any judicial inquiry, though demands are growing for one in the wake of the publication of the Saville report on Bloody Sunday. In that context, Ballymurphy is now regularly referred to as ‘Belfast’s Bloody Sunday’—a nomenclature that, even as it seeks to generate attention for these particular victims of state-sponsored violence, also derives its memorability, and its claims to justice, from its perceived similarity to the more salient event. So far demands for an inquiry relating to these particular victims have been rejected, however, on the grounds that such a review would not provide ‘answers which are not already in the public domain’.[3]

So what has made Bloody Sunday more memorable than Ballymurphy? The very different mnemonic trajectories of these two actrocities could only be fully explained by a closer analysis of the politics of remembrance in Northern Ireland against the background of a deeply-fraught peace process in which the desire for historical justice continuously struggles against the desire for closure. In what follows, however, it is the specifically cultural factors underpinning the differential distribution of memorability that I wish to explore.

The most obvious difference between the two atrocities has already been mentioned: the fact that Bloody Sunday from the get-go became the subject of intense mnemonic investment in multiple media and genres. Bearing in mind the scarcity principle, one might speculate that there was only ‘room’ in the mnemonic economy of Northern Ireland for one major site of memory relating to the killing of un-armed civilians by members of the British army. What is certain is that the chances of Bloody Sunday occupying that salient position were enhanced by the insult-added-to-injury of the Widgery report. This official report, hastily produced in the immediate aftermath of Bloody Sunday, had explicitly denied the unlawfulness of the killing of the demonstrators and instead justified it as a legitimate response to terrorist threats. This meant that the desire for historical justice which fed the recursive representation of Bloody Sunday became compounded, and rendered all the more urgent, by the perceived need to ‘undo Widgery’ and over-write its egregious un-truth. Over the years, the campaign to overturn Widgery thus fuelled the desire to represent Bloody Sunday in a more truthful way in whatever cultural forms were available.

This intense public preoccupation with Bloody Sunday in the years and decades following the atrocity goes a long way to explain its current salience relative to Ballymurphy. But the post-hoc remembrance does not tell the whole story. The memory of ‘Bloody Sunday’ did not actually begin in 1972, but much earlier. The events in Derry activated in their very occurrence the memory of multiple other ‘Bloody Sundays’. When the Derry atrocity entered into ‘the figurability of the present’, to use Kristin Ross’s phrase (Communal Luxury 2), it did so as a new instantiation of a powerful event-type that had developed over the course of at least a century. This event type combined civic activism, massacre, and melodrama.

Civic Movements, City Memories

Derry’s Bloody Sunday was a singular event at the same time as it belonged to a tradition of civic massacres, events in which a peaceful demonstration by citizens is violently suppressed by state forces. Beginning with the so-called Massacre of the Champs de Mars in Paris in 1791, the civic massacre can be seen as a specifically modern genre, related to the political condition of democracy where the will of the nation aims to be represented in the workings of the state and citizens have the right to demonstrate. Civic massacres, as their association with particular squares and parks below indicates, are also linked to modern conditions of urban living and the availability of squares and parks in which citizens assemble to air their hopes and grievances (see Mitchell, Harcourt and Taussig). While the causes brought into play in these demonstrations alternate between workers’ rights, civil rights, and the right to national self-determination among others, the central opposition between active citizens and state terror remains a constitutive feature of the event type.

Table 1

Table 1 provides a canon of civic massacres reconstructed using digital searches in newspaper archives, Wikipedia, and other online and print resources, taken as indicative of the public discourses surrounding these events.[4] The left-hand column lists those events that have come structurally to be known as ‘Bloody Sunday’ (be this in English or another language). The central column lists massacres that are primarily known by other names (‘Selma’, ‘Maidan Square’ etc.), but are sometimes referred to as a ‘Bloody Sunday’. Finally, the right-hand column lists massacres that are known above all by the place in which they occurred but which are often compared multidirectionally (Rothberg Multidirectional Memory) to Bloody Sunday or to each other (as when the Peterloo massacre of 1819 was invoked as an antecedent for the events in Trafalgar Square in 1887[5]). As we shall see, the use of the term ‘Bloody Sunday’ with reference to these multiple events reflects the entanglement in both history and memory of internationalist socialism, anti-colonialism, and particular nationalisms.

The term ‘canon’ is justified here by the commonly-expressed view that these events belong together: they provided mutual points of reference for calibrating atrocity and thus resonated with each other. The word resonance should be understood here in the strong sense of vibration, meaning in this case that the affective and symbolic impact of one event, as known through the media, can be picked up at another time and another place in such a way as to create ‘scripted linkages’ between the actors involved.[6] The phenomenon of resonance is linked to premediation (Erll), understood as the ways in which the understanding of new events can be informed by the representation of earlier ones (Erll shows for example how the earlier representations of the Indian Mutiny of 1857 informed—premediated—the understanding of later events in colonial India). ‘Resonance’, however, involves more than the application of a cognitive schema in the experience of new events. It includes the self-conscious awareness that an event-type is being instantiated again at a different time and place, such that the affect of one outrage is transferred to the other and affiliations created between distant actors. The accumulative recurrence of the name ‘Bloody Sunday’ is symptomatic for the participants’ awareness of this resonance: that in some way the ‘same’ event is happening over and again, with each new Bloody Sunday working accumulatively to build up a long-term memory of civic massacres that is multi-sited (Marcus) as well as highly-localised. Each ‘Bloody Sunday’ is thus a singular event at the same time as it is grafted onto the memory of other massacres as these have travelled through the media and the arts with the help of transnational networks of activists. The analysis of such repetitions calls for an understanding of time that includes the non-linear temporalities brought into play by historical injustice (see Bevernage) and by hope (Ross, May ‘68 and its Afterlives; Ross Communal Luxury).

Multi-sited Protests

Given the number of civic massacres mentioned earlier, it is impossible to deal with them all in any detail. Suffice it here to sketch the most important antecedents that played into the prefiguration of Bloody Sunday 1972 and indicate how they echoed and referred to each other. The digital archives of nineteenth-century English-language newspapers indicate that the first ‘Bloody Sunday,’ and the prototype for the ones which followed elsewhere, took place in 1887. It involved a demonstration in Trafalgar Square in London on Sunday, 13 November 1887, when some 10,000 people marched to demonstrate against a recent coercion bill which had restricted the citizen’s right to protest. The marchers’ approach to Trafalgar Square was brutally halted by the police and army, which led to many injuries and, indirectly, three fatalities. The demonstration had involved a coalition of various workers’ associations, socialist intellectuals like William Morris and George Bernard Shaw, and activists involved in the movement for Irish independence. As we shall see, this mixed genealogy in internationalist socialism and in Irish nationalism would be reflected in later uses of the term ‘Bloody Sunday’, with opposition to the status quo and the hope of changing it through peaceful protest being the common denominator.

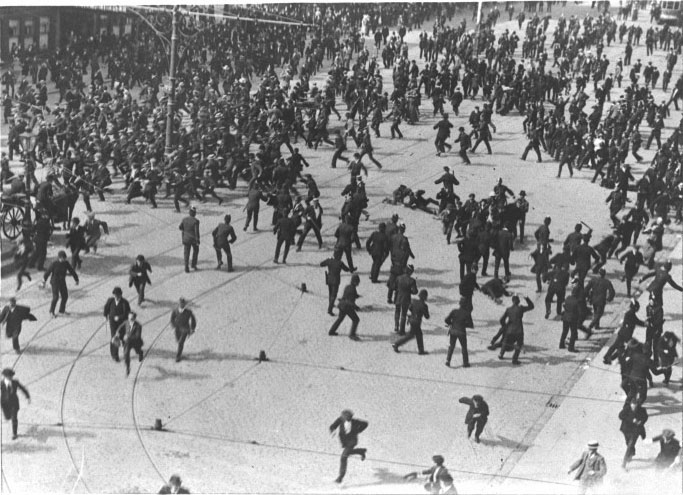

Figure 2: Riot in Trafalgar Square (1887); Graphic 19 November 1887. Public domain.

The events in Trafalgar Square were described initially as a ‘disturbance’ or ‘riot’ and the latter was the term of choice in the London Illustrated Weekly (26 November 1887). A close study of the British and Irish press over a period of several months suggests that the name ‘Bloody Sunday’ was first used on 14 November in a protest poster displayed outside the Rotherite Radical Club[7], and that this name ultimately ‘stuck’ across the board, among both supporters and critics of the original demonstration. Within a couple of days, references were made to the event that ‘the working men of London are beginning to call “Bloody Sunday”’, and a couple of years later to ‘that day now known in the melodramatic parlance of visionary politicians as “Bloody Sunday”’.[8] Those ‘visionary politicians’, William Morris foremost among them, were indeed active in ‘branding’ the event and, linked to this, in ensuring that it would not be forgotten. In November 1888 a new demonstration was accordingly organised in Hyde Park on the occasion of the first anniversary of Bloody Sunday. Indicative of the internationalist orientation of the activists involved, the same occasion was also used to commemorate the so-called ‘Chicago martyrs’, the eight American anarchists who had been executed in the previous year.[9] The linking of the two events illustrates how the memory of Bloody Sunday was actively cultivated so as to give extra traction to the causes, both nationalist and internationalist, for which people had originally demonstrated. In keeping with this principle, Bloody Sunday figured on the socialist Commonweal’s revolutionary calendar for 13 November 1888 alongside the trial of the Scottish Chartists in 1848 and the prosecution of Richard Pigott in 1861 for having forged documents detrimental to the cause of the Irish Home Rule movement.[10] In this way, ‘Bloody Sunday’ was embedded as a memory site within a larger revolutionary canon of key events, heroes, and martyrs whose memory fed into the continued pursuit of shared ideals that crossed the boundaries of states and nations. This remarkable conjunction of commemoration and activism belies the commonly-held idea that future-oriented revolutionary movements are by definition amnesic and that memory is always backward looking. We are dealing here with the memory of a cause, and of commemoration with a cause, an energising combination where the past and future reinforce each other.[11]

The next major ‘Bloody Sunday’—a key memory site of the Russian Revolution and the international workers’ movement—took place in Saint Petersburg in 1905, when unarmed demonstrators marching to present a petition to Tsar Nicholas II were fired upon by soldiers of the Imperial Guard. Calculations of the number of fatalities have varied enormously, but the consensus among historians would now seem to put the figure at around 1,000 dead. In his Road to Bloody Sunday (261n), Walter Sablinsky has linked the name ‘Bloody Sunday’ to the Irish journalist E.J. Dillon, a reporter for various British and American newspapers, who claimed responsibility for having first applied this term.[12] The subsequent appropriation of the English name into Russian would have been facilitated by the fact that the Trafalgar Square event was also known in Russia through the international socialist movement.[13]

Figure 3: Still from Vyacheslav Viskovsky Devyatoe Yanvarya (1925), representing Bloody Sunday in St. Petersburg 1905; Wikimedia commons.

Figure 3: Still from Vyacheslav Viskovsky Devyatoe Yanvarya (1925), representing Bloody Sunday in St. Petersburg 1905; Wikimedia commons.

Whatever its exact origin, the name ‘Bloody Sunday’ (or rather its Russian equivalent: Крова́вое воскресе́нье) became the standard term in Russian. Crucially, it was the term used by Lenin when he gave a lecture in Zurich in January 1917 commemorating the 1905 Revolution as well as anticipating the Revolution-to-come: ‘Today is the twelfth anniversary of “Bloody Sunday”, which is rightly regarded as the beginning of the Russian revolution’ (Lenin). In the English-speaking press the event had also become widely known as Saint Petersburg’s Bloody Sunday, a nomenclature that invited retrospective linking to the much less bloody violence in Trafalgar Square. In January 1906, reflecting the internationalist commemorative culture mentioned earlier, the first anniversary of the Saint Petersburg massacre was commemorated by Toronto socialists as part of the ‘international celebration, held world-wide, of the first anniversary of “Bloody Sunday”, the eventful day when hundreds of Russian workmen were slaughtered by the Cossacks of capitalism in St. Petersburg’ (The Globe, 22 January 1906).The next important antecedent for the 1972 Bloody Sunday, and the one most immediately at play in Irish responses, was the Dublin Bloody Sunday of 21 November 1920 at the height of the Irish war of independence. The naming of the violence on that day has had a complicated history because it actually involved two sets of killings: in the morning, the assassination of 12 suspected British spies by Irish independence fighters; in the afternoon, the reprisal killing by the British army of 14 civilians attending a Gaelic football match at Croke Park (since 1884 the symbolic centre of Irish national sports). It would appear that the term ‘Bloody Sunday’ was used initially in the pro-British press, in an ironic appropriation of the Trafalgar square prototype, with reference to the assassination of suspected English spies in the morning rather than to the killings by the British army at Croke Park later that afternoon.[14] The Freeman’s Journal reported the next day (22 November 1922) on ‘Dublin’s Bloody Sunday’ with reference to the day as a whole, but with a particular emphasis on the afternoon. And in the long term it is the afternoon as ‘Bloody Sunday’ which has dominated in Irish national memory, in the process over-writing the memory of the assassinated British agents. It retrospectively also upstaged and occluded the memory of the violent suppression of strikers in 1913 which had initially been seen, in an echo both of Trafalgar Square and possibly also Saint Petersburg, as Ireland’s ‘first Bloody Sunday’.[15] The centrality of Dublin’s 1920 Bloody Sunday was later strengthened by its being the subject of an annual commemoration in the following decades, with its salience later reflected in the fact that it was one of a select number of locations visited in 2011 by Queen Elizabeth on the first state visit of a British monarch to post-independent Ireland.

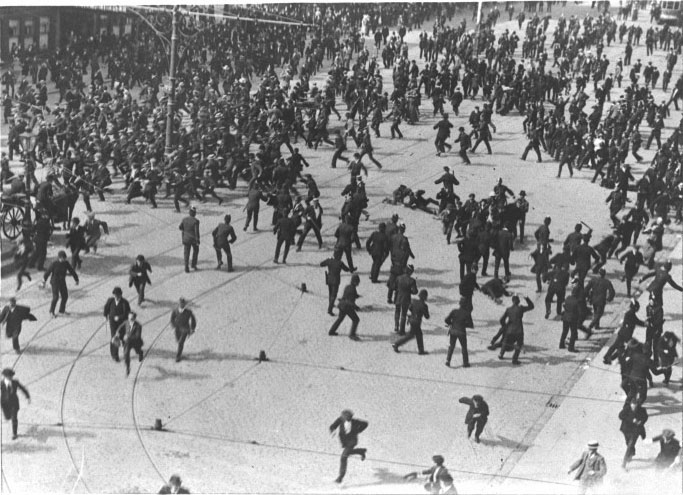

Figure 4: Baton charge of the Dublin Metropolitan Police during the Dublin Lockout (1913); © RTÉ Stills Library (Cashman Collection).

Figure 4: Baton charge of the Dublin Metropolitan Police during the Dublin Lockout (1913); © RTÉ Stills Library (Cashman Collection).

It seems plausible that the cultural memory of these earlier Bloody Sundays—Trafalgar Square, Saint Petersburg, and the 1913 strike—played into the emergence of ‘Bloody Sunday’ as the name par excellence to sum up the Croke Park massacre.[16] Even though the Freeman’s Journal had reported on both morning and afternoon events as part of the same cycle of violence, the very choice of ‘Dublin’s Bloody Sunday’ as the key term meant that the killings were self-consciously inscribed in a tradition which pitted civic liberties and activism against repression, innocent citizens against state violence. This tendency was further enhanced by the evocation, in the same article, of the recent memory of the Amritsar massacre of 1919 (the killing of hundreds of Indian demonstrators by British soldiers) as a further point of comparison: yesterday ‘Croke Park was turned into Amritzar’ (sic), wrote the Freeman’s Journal. The idea that one place (‘Croke Park’) could be perceived as having been transformed into another place thousands of miles away (‘Amritsar’) is indicative of the thickening both of space and time which the idea of a ‘Bloody Sunday’ could multidirectionally bring into operation. ‘Bloody Sunday’ as an event-type could link Amritsar, Dublin, Trafalgar Square, Saint Petersburg as part of a multi-sited, but shared experience of (colonial, class) repression that was all the more outrageous precisely because it attacked innocent citizens as they optimistically exercised their rights. At first sight the Dublin case would seem to be an exception since it involved a football match rather than a demonstration, but the question of rights played a role here too since Gaelic sports were closely linked at the time to cultural self-determination.Much more could be said about all of these events. But suffice it here to point to the occurrence of multiple cross-references in which local, national, and international frameworks were brought into play. The result is the ongoing transfer of a multi-sited, specifically urban memory that connects one city to another through the shared experience of state violence against an active citizenry.

Bloody Sunday 1972

The shootings of demonstrators in Derry in 1972 occurred against the background of this deep memory of massacre and its multiple representations. Although it has proven difficult to pinpoint exactly when the shootings in Derry became known as Bloody Sunday, it seems to have occurred very quickly. Within less than 24 hours an editorial in the Dublin-based Irish Times (31 January 1972) was inscribing the events in a sinister tradition, as part of the transnational canon: ‘Sharpeville, Amritsar, and Bloody Sunday 1920—the parallels are inadequate’. This was echoed a week later in a poem entitled ‘Elegy for Bloody Sunday, Derry 1972’ that was published in the Ulster Herald and that refers to the ‘vivid bloodgash memory / of murder in the streets / Sharpeville, Amritsar, Bloody Sunday, Derry 1972’.[17] The name ‘Bloody Sunday’ thus very quickly and very firmly ‘stuck,’ so much so that the findings of the official Saville inquiry were entitled ‘Report of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry’ (2010); and that when Prime Minister Cameron subsequently offered his official apology for these events, he explicitly referenced ‘the tragic events of 30 January 1972, a day more commonly known as Bloody Sunday’.[18] Indeed, the name ‘Bloody Sunday’ has become so powerfully associated with the events in Derry in 1972 that for the time being at least, they would appear to have become the new mother-ship ‘Bloody Sunday’ that has retrospectively transformed all precedents into variants of this prototype: Dublin’s Bloody Sunday, Belfast’s Bloody Sunday, Vancouver’s Bloody Sunday (Brodie 1974), and so on. It has become an internationally-known yardstick in interpretations of state violence against protestors. Illustrative in this regard is the fact that in 2009 Paul Greengrass’s movie Bloody Sunday (2002) was screened as part of the bicentenary commemorations of a nationalist uprising in South Tirol in 1809. Its relevance lay in the fact that another ‘Bloody Sunday’ is central to Tirolean memory: the ‘Blutsonntag’ which took place in Bozen, South Tirol in 1921 when Italian fascists killed German-speaking demonstrators.[19] In recent years, the music group U2 has been inflecting their world-famous song ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ so as to highlight its resonance with various ongoing causes outside of Ireland, most notably that of the Iranian protest movement of 2009.[20] In doing so, they are continuing a longer tradition of internationalist activism.

When the 14 victims of Derry’s Bloody Sunday are now compared with the 11 Ballymurphy victims (with which I began this essay), it becomes evident that the affective and symbolic impact of the Derry killings was enhanced by their resonance with the long-term memory of other ‘Bloody Sundays’. Together the 1972 killings fitted into an event-type whereas the killings in Ballymurphy did not, being drawn out over several days and not involving demonstrators. The weight of a multi-sited history was thus brought to bear on Bloody Sunday, allowing those remembering it to make common cause (Gandhi) with citizens at other locations, with a long history of state violence and with the more recent history of the civil rights movement in the US, including ‘Selma’, America’s 1965 ‘Bloody Sunday’.The very strength of the event-type in turn begs the question why ‘civic massacres’ in particular are so memorable. The combination of the right to protest and concentrated state violence has a ‘stickiness factor’ (Gladwell) that calls for further explanation.

Melodrama and Massacre

Why certain events or event-types are recalled over and again in new situations while others are forgotten, and why some stories travel across national borders and others do not, is something that has been under-studied and under-theorised in memory studies. The concept of trauma has been useful up to a point in explaining the cultural recurrence of the preoccupation with outrage. But following what was said earlier about the differential distribution of memorability, the fact that particular events are traumatic to those directly involved does not guarantee them a significant afterlife in cultural memory. The killings in Ballymurphy offer a case in point. So do cases of structural oppression and deprivation where violence is continuous rather than disruptive (see Craps).

As Rob Nixon has demonstrated in his Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, the slow violence of poverty and the quotidian traumas of radical inequality have not traditionally lent themselves to narration and representation in the same way as critical eruptions of violence (Nixon). Following this insight, we can say that the unequal distribution of our memory of violence is not simply the outcome of indifference to particular victims or classes of victims (though this too is involved), but also of the fact that ‘slow violence’ is less easily recollected as a story than an attention- and affect-grabbing outburst such as a massacre, which is concentrated in a short period of time and offers a quasi-Aristotelian unity of time and place. The sad reality is that massacres are eminently narratable. Concentrated acts of violence thus provide a potent resource for encapsulating long-term structural inequalities in an intensely dramatic way. It is presumably for this reason that Rachid Bouchareb’s film Hors-la-loi (Outside the Law 2010), about the Algerian liberation struggle, begins with the massacre in Sétif in 1945 and ends with one in Paris in 1961.

Hayden White once defined narrativity in terms of a conflict between ‘desire’ and the ‘law’ (White). Following this line of thought, civic massacres can be said to be particularly memorable because they exemplify the very essence of storytelling in pitting aspirations and hope against state-sponsored violence. Even more importantly, they bring into play what Peter Brooks has called the ‘melodramatic imagination’ (Brooks). In The Melodramatic Imagination Brooks definitively put paid to the idea that melodrama is a culturally insignificant form of overly sentimental kitsch, arguing instead that it is the aesthetic mode par excellence of modernity. He showed how melodrama emerged from the French Revolution, its cultural predominance thus coinciding with the growth of modern cities and of democratic political cultures, where it provided an imaginative resource for negotiating ‘moral legibility’ in a changing world. Melodrama works through dramatisation, emotivity, and moral polarisation whereby the conflict between good and evil, between villainy and innocence, is made hyperbolically visible in a secular form of revelation. In particular, as Linda Williams has added, this moral legibility is linked to a dialectic of pathos and action, in which victimhood and ‘the exhilaration of action’ are held in an emotively charged balance (Williams 30). Seen in this way, the aesthetics of melodrama should be taken seriously both as a tool of moral legibility and as one of the vehicles par excellence of what has recently been called the ‘cultural politics of emotion’ (Ahmed).

One of the recurrent figures mentioned by Brooks as encapsulating melodrama, and which seems particularly relevant to our case here, is that of the ‘interrupted feast’. This is typically a moment of innocent celebration which is radically interrupted by the forces of evil such that, in a shocking reversal, celebrators become victims. The melodramatic force of such reversals can help explain the special importance of ‘Sundays’ in the canon of massacres. That historically there should been so many demonstrations in modern cities on a Sunday is of course simply an offshoot of the fact that this was generally when people had some free time. But it also made the violence perpetrated by the forces of the state against law-abiding citizens exercising their rights on their ‘free day’—especially their rights to demonstrate for a better world—all the more shocking.As a form of melodrama, ‘Bloody Sunday,’ dramatises and makes manifest a moral configuration where innocence is pitted against culpability, right against might, citizenry against the state, hope against its destruction. As a figure of memory, ‘Bloody Sunday’ combines both victimhood and agency or, to use Williams’ terms, the dialectic of pathos and action: on the one hand, the suffering at the hands of state forces; but on the other hand, the agency of demonstrators seeking to achieve change through peaceful protest and, later, the agency they exercise in running away. Bloody Sunday thus melodramatically dramatises modern citizenship and configures structural concerns about the actual ‘power of the people’ to exercise their rights in a modern democracy.

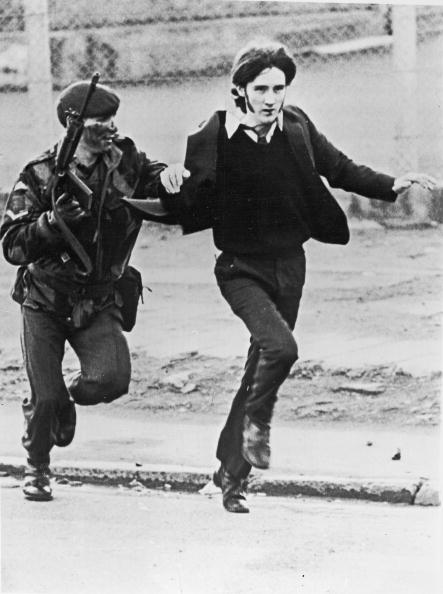

Figure 5: British paratrooper takes a captured youth from the crowd on ‘Bloody Sunday’ (1972); Getty Images News.

Figure 5: British paratrooper takes a captured youth from the crowd on ‘Bloody Sunday’ (1972); Getty Images News.

Not only is this tension between victimhood and agency implicit in the verbal accounts of these events, it is also made manifest in the rich visual archive of Bloody Sundays, the first of which coincided with the heyday of the illustrated press. The resonance between these multiple Bloody Sundays is also enhanced by echoes between iconic images and their depictions of movement. The underlying drama of ‘citizens in action’ becoming victims of state violence is performed over and again in photographs and drawings that capture the movement of the crowd as they first assert their right to demonstrate and then have to flee from violence. The paradoxical combination of victimhood and agency, of powerlessness and empowerment, feeds into the mobilising power of such images, exemplifying Aby Warburg’s concept of Pathosformel (Pathosformula), a visible constellation with the power to arouse deep memory and deep affect (Hurttig).[21]Together these considerations support the claim that melodrama is key to the resilience of Bloody Sunday as an event-type and to the cultural work it does in articulating outrage. It also provides the key to its capacity to articulate a distinct mode of remembrance that is both forward-looking and memorialising.

Conclusion

To highlight the melodramatic underpinnings of Bloody Sunday as an event-type is not to diminish the gravity of historical injustice by somehow reducing it to a ‘merely’ aesthetic phenomenon. It is instead an attempt to understand better the enabling role of aesthetics in shaping and articulating memories, in capturing outrage and in communicating it to the world at large in an affective and mobilising way. Being able to capture outrage also helps in re-capturing the causes to which the murdered citizens were committed.

There is of course a price to be paid: the melodramatic memorability of massacre means that some events are upstaged at the cost of others, or at the cost of failing to grasp the ‘slow violence’ of chronic injustice or the singularity of individual suffering. Bearing in mind that memory can never be egalitarian, however, and that the price of long-distance solidarity may be the ability to arouse a particular intensity of emotion or answer to a particular type of legibility, the best we can probably do with this finding is to continue to explore further the conditions under which events make their mark across national borders and the occlusions which are the byproduct of such salience.But one thing is already clear: memory and activism are deeply entangled in ways that we are only just beginning to understand (see Reading and Katriel). In the cases studied here, the commemoration of outrage fed back into the broader struggle to which the original demonstrations belonged—be this an internationalist struggle for workers’ rights, a struggle for national self-determination, or a struggle for civil rights. Establishing a more extensive archive of activist memory—memory of a cause and memory with a cause—is a desideratum in memory studies. Especially if combined with a transnational approach that is alert to the interactions of the different social frameworks of memory, it would help the field move beyond the over-emphasis on the traumatic and on victimhood, and to think more clearly about the ways in which remembering the past and shaping the future can work together.

[sta_anchor id=”bio”]Ann Rigney is professor of Comparative Literature at Utrecht University, where she also convenes the Utrecht Forum for Memory Studies. She has published widely in the field of cultural memory studies and historical fiction. Her books include The Afterlives of Walter Scott: Memory on the Move (OUP, 2012), Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory (edited with Astrid Erll, 2009), Commemorating Writers in Nineteenth-Century Europe (edited with Joep Leerssen, 2014), and Transnational Memory (edited with Chiara De Cesari, 2014). www.rigney.nl

Notes

[1] My thanks to Marek Tamm for provoking me into inquiring further into the prehistory of Bloody Sunday 1972. I am also grateful to Yesim Yildiz and Yasemin Yildiz for help with the Turkish cases.

[2] For an overview of the artistic production related to Bloody Sunday 1972, see especially Herron and Lynch. The artistic corpus includes poems by Seamus Heaney (‘Casualty’, 1979) and Thomas Kinsella (‘Butcher’s Dozen’, 1972), work by video-installation artist Willie Doherty (30 January 1972, 1993), plays by Brian Friel (Freedom of the City, 1973) and Frank MacGuiness (Carthaginians, 1988), films by Paul Greengrass (Bloody Sunday, 2002) and Richard Norton-Taylor (Bloody Sunday: Scenes from the Saville Inquiry, 2005), and songs by John Lennon (‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’, 1972) and U2 (‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’, 1983).

[3] Statement by Theresa Villiers, Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, 29 April 2014. <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/decision-on-ballymurphy-independent-review-panel>.

[4] This list does not claim to be exhaustive. Among others, it omits a 1900 Bloody Sunday (used to describe the battle of Paardeberg), whose naming seems to reflect more the number of casualties than the event-type being discussed here, and also the ‘Bromberger Blutsonntag’, which phrase was used by the Nazis (a remarkable appropriation of the event-type) to describe the deaths of Germans at the hands of Poles in 1939. As digital archives and Wikipedia further facilitate the uncovering of transnational connections and examples beyond Europe, the list of Bloody Sundays and other civic massacres can also be expected to grow and hence to complicate even further the picture presented here.

[5]Pall Mall Gazette, 14 December 1887.

[6] The phrase ‘scripted linkages’ is used here by way of counterpart to the idea of ‘unscripted linkages’ in Rothberg, ‘Multidirectional Memory’, 150.

[7]The Times, 15 November 1887. For more details, see the contrasting accounts of the London Illustrated Weekly (26 November 1887) and Morris.

[8]Pall Mall Gazette, 15 November 1887; Green Bag 4 (1892). For other uses of the term ‘Bloody Sunday’ see also: Westminster Review 128, issue 109 (1887); Commonweal, 10 November 1888;Birmingham Daily Post, 16 November 1887; The New England Magazine 16 (1897).

[9] According to The Times (12 November 1888), the anniversary meeting in Hyde park was attended by some 4,000 people holding banners that read ‘Remember Trafalgar-square’ and ‘Remember Chicago, November, 1887’. For details see United Socialist Societies. See also ‘Chicago Martyrs & Bloody Sunday’, Commonweal, 3 November 1888.

[10]Commonweal, 10 November 1888.

[11] See also the account of Morris’ celebratory commemoration of the Commune in Ross, Communal Luxury. For a more ethnographic approach to the memory of activism, see Marlière.

[12] Sablinsky refers to Dillon, The Eclipse of Russia, 157, where Dillon refers to ‘the public procession to the Winter Palace on the historic 22nd January, to which I afterwards gave the name of “Bloody Sunday”’. Although Dillon refers a few lines earlier to his 1905 reports on the killings in Saint Petersburg, there is no direct evidence in the sources he gives that he actually used the term ‘Bloody Sunday’, although he might have considered it implicit in his various accounts of the ‘bloodbath of Sunday 22 January’ (Dillon, ‘World Politics’ 460; Dillon ‘The Situation in Russia’).

[13] A narrative of the Trafalgar Square events was provided for example in Русскоебогатство: Russkoe bogatstvo [Russian abundance: A Literary, Scientific, and Political Journal] (1903), 12. My thanks to Anastasija Pupynina and Neil Stewart for their invaluable help in checking the Russian sources.

[14]The Herald (Glasgow), 23 November 1920; Pall Mall Gazette, 22 November 1920; The Times, 23 November 1920; The Daily Telegraph, 23 November 1920; Daily Mail , 23 November 1920; Daily Herald, 23 November 1920; Leeds Mercury, 23 November 1920; Manchester Guardian, 23 November 1920; Nenagh Guardian, 27 November 1920. Critiques of the tendency of nationalist memory to overlook the morning victims are offered in Bowden 1972; and especially Dolan 2006.

[15] The violence against strikers in 1913 was called ‘Ireland’s first Bloody Sunday’ in the Kerryman, 22 January 1916, and ‘Dublin’s Bloody Sunday’ in the Irish Independent, 29 July 1914. The deaths of 22 civilians as a result of sectarian violence in Belfast on 20 July 1921 were initially known as ‘Belfast’s Bloody Sunday’ (Parkinson). But this name did not ‘stick’, presumably because it was upstaged by Dublin 1920, but also because it did not fully answer to the event-type (the deaths were on a Sunday, but involved sectarian violence rather than state terror against demonstrators); this meant that the Ballymurphy massacre, as mentioned earlier, could later be called ‘Belfast’s Bloody Sunday’. For a similar reading of the shifting nomenclature of the Belfast violence of 1921, see <http://www.theirishstory.com/2010/06/24/four-bloody-sundays/#.ViJ6hX4rLiw>. 15 Oct. 2015.

[16] The 1905 Bloody Sunday was well-known in Ireland, as evidenced in the Freeman’s Journal, 29 October 1905 and 30 December 1905.

[17] Signed Raymond na Hatta (pseudonym of Stephen McKenna), Ulster Herald, 5 February 1972.

[18] House of Commons Debate 15 June 2010, vol 511, col 739. <http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmhansrd/cm100615/debtext/100615-0004.htm>.

[19] <http://www.1809-2009.eu/v2/textversion/detail.php?artnr=8031&ukatnr=10584>. On the Tirol massacre see: Steininger; Thaler and Mumelter. I am very grateful to Susanne Knittel for drawing my attention to this case.

[20] The causes espoused by U2 through their song range so widely as perhaps to prelude the end of Bloody Sunday’s specific association with civic demonstrations. See <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunday_Bloody_Sunday>.

[21] For an exemplification of Warburg’s ideas about images in movement see the project by Georges Didi Huberman at <http://creative.arte.tv/fr/community/histoire-de-fantomes-pour-grandes-personnes-georges-didi-huberman-arno-gisinger?language=en>. With thanks to Astrid Erll for this reference.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sarah. The Cutural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

The Ballymurphy Massacre. Dir. Sean Reynolds, Kyle Gibbon and Jonny Lewis, 2012.

Bevernage, Berber. History, Memory, and State-Sponsored Violence: Time and Justice. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Bowden, Tom. ‘Bloody Sunday—A Reappraisal.’ European Studies Review 2.1 (1972): 25-42.

Brodie, Steve. Bloody Sunday: Vancouver 1938: Recollections of the Post Office Sitdown of Single Unemployed. Vancouver: Young Communist League, 1974.

Brooks, Peter. The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess. 1976. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1995.

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? London: Verso, 2009.

Conway, Brian. Commemoration and Bloody Sunday: Pathways of Memory.Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Craps, Stef. Postcolonial Witnessing: Trauma out of Bounds. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Dawson, Graham. Making Peace with the Past?: Memory, Trauma and the Irish Troubles. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2007.

De Cesari, Chiara, and Ann Rigney. ‘Introduction.’ Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales. Eds. Chiara De Cesari and Ann Rigney. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014. 3-25.

Dillon, E.J. The Eclipse of Russia. London: J.M. Dent, 1918.

—. ‘The Situation in Russia.’ The Contemporary Review 87 (March 1905): 305-32.

—. ‘World-Politics. London: St. Petersburg: Paris: Washington.’ North American Review 180.580 (1905): 453-80.

De Cesari, Chiara, and Ann Rigney, eds. Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014.

Dolan, Anne. ‘Killing and Bloody Sunday, November 1920.’ Historical Journal 49.3 (2006): 789-810.

Erll, Astrid. Prämediation—Remediation: Der Indische Aufstand in Imperialen und Post-Kolonialen Medienkulturen (1857 bis zur Gegenwart). Trier: WVT, 2007.

—, and Ann Rigney, eds. Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2009.

Gandhi, Leela. The Common Cause: Postcolonial Ethics and the Practice of Democracy, 1900-1955. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2014.

Gladwell, Malcolm. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. New York: Little Brown, 2000.

Hayes, Patrick, and Jim Campbell. Bloody Sunday: Trauma, Pain and Politics. London: Pluto Press, 2005.

Herron, Tom, and John Lynch. After Bloody Sunday: Representation, Ethics, Justice. Cork: Cork UP, 2007.

Hurttig, Marcus Andrew. Die entfesselte Antike: Aby Warburg und die Geburt der Pathosformel. Köln: Walther Hönig, 2012.

Lenin, Vladimir. ‘Lecture on the 1905 Revolution.’ Lenin Collected Works. Vol. 23. Trans M. S. Levin et al. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1964. 236-53. <www.marxists.org>.

Marcus, George E. ‘Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.’ Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (1995): 95-117.

Marlière, Philippe. La mémoire socialiste 1905-2007: Sociologie du souvenir politique en milieu partisan. Paris: Harmattan, 2007.

Mitchell, W. J. T., Bernard E. Harcourt and Michael Taussig. Occupy : Three Inquiries in Disobedience. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2013.

Morris, William. ‘London in a State of Siege.’ Commonweal 3.97 (19 November 1887): 369-70.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2011.

Nora, Pierre, ed. Les lieux de mémoire [1984-92]. 3 vols. Paris: Gallimard, 1997.

Parkinson, Alan F. Belfast’s Unholy War. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2004.

Reading, Anna, and Tamar Katriel, eds. Cultural Memories of Non-Violent Struggles: Powerful Times. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Rigney, Ann. ‘Do Apologies End Events? Bloody Sunday, 1972-2010.’ Afterlife of Events: Perspectives on Mnemohistory. Ed. Marek Tamm. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. 242-61.

—. ‘Plenitude, Scarcity and the Circulation of Cultural Memory.’ Journal of European Studies 35.1 (2005): 209-26.

Ross, Kristin. Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune. London: Verso, 2015.

—. May ‘68 and its Afterlives. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2002.

Rothberg, Michael. ‘Multidirectional Memory in Migratory Settings: The Case of Post-Holocaust Germany.’ Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales. Eds. Chiara De Cesari and Ann Rigney. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014. 123-45.

—. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2009.

Sablinsky, Walter. The Road to Bloody Sunday: Father Gapon and the St. Petersburg Massacre of 1905. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1976.

Steininger, Rolf. South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century. Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2003.

Thaler, Elmar, and Norbert Mumelter, eds. 24. April 1921, Der Bozner Blutsonntag. Zirl: Edition Südtiroler Zeitgeschichte, 2011.

United Socialist Societies. Chicago Martyrs and Bloody Sunday. London: n.p., 1888.

White, Hayden. ‘The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality.’ The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 1987. 1-25.

Williams, Linda. Playing the Race Card : Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2001.