By Rachel Fetherston, Emily Potter, Kelly Miller and Devin Bowles

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version. doi: 10.56449/14233338

In their work on how narrative may help audiences think differently about other species, Wojciech Malecki et al. refer to the ‘narrative turn’ within academia and its proliferation of research that addresses how ‘moral intuitions often yield to narrative persuasion’ (2). In other words, many scholars are currently asking whether narratives can persuade readers to reflect on and perhaps reconsider their own moral beliefs. The research presented in this paper follows a similar trajectory in its discussion of the results and possible implications of a reader response study that investigated how Australian readers respond to works of Australian eco-crime fiction that portray non-humans and global ecological issues such as climate change in a local Australian context. Resonant with ‘narrative persuasion’—the idea amongst social scientists that ‘a narrative is a catalyst for perspective change’ (Hamby et al. 114)—we consider the capacity of such texts to possibly engage readers with the plight of non-humans in Australia under the impacts of climate change.

This study employed reader response methodology to determine some of the key themes that Australian readers are drawn to when reading Australian eco-crime fiction, with particular emphasis placed on understanding their responses to representations of the non-human and associated environmental issues in these texts. While this study originally focused on literary as well as genre ecofiction, this paper focuses in a more targeted way on the reader responses to Australian crime fiction texts which we are also defining as ecofiction. Our hope is that this emphasis on genre fiction provides a pathway to future researchers wanting to understand how different readers respond to and are influenced by a broader environmental literature—one that is inclusive of popular genre texts as well as more literary works. In this paper, we discuss the qualitative results of a reader response survey, with a particular emphasis on how readers may be interpreting, or not interpreting, Australian eco-crime works. We believe this study brings together two different modes of literary studies practice in a productive manner, highlighting the complementary relationship between reader response methodology and ecocritical thought. This relationship is yet to be utilised to its full potential by ecocritics and social scientists wanting to understand how narrative affects audience perspectives on the natural world.

This research therefore sits partly within the emerging field of empirical ecocriticism, which is defined as ‘combin[ing] social scientific methodologies with the kind of textual analysis that has long been the métier of ecocriticism’ (Schneider-Mayerson et al. 329). In many ways, it is a response to the following question put by Matthew Schneider-Mayerson: ‘How do the assumptions and intuitions of ecocritics align with empirical evidence about what environmentally engaged narratives do when they encounter flesh-and-blood readers?’ (‘“Just as in the Book”?’ 2). Or, in the context of this study, how do readers’ responses to Australian eco-crime fiction align with ecocritical assumptions about the representation of nature and the non-human in these texts? The results of this study provide a means for ecocritics to better understand and even reconsider their own readings of these same, or similar, narratives.

Crime Fiction as Ecofiction

We identify Australian ecofiction as a genre because it exhibits certain tropes that are expected by the reader, as will be outlined shortly.[1] Australian ecofiction encompasses speculative and science fiction, crime fiction, and realist fiction, amongst other forms. Some common tropes of the genre of Australian ecofiction include the portrayal of the present and future impacts of anthropogenic climate change,[2] environmental activism, environmental exploitation such as logging, mining and farming, the depiction of various non-humans, and an exploration of human-non-human relationships. While such characteristics can no doubt be applied to the conceptualisation of ecofiction more broadly, Australian ecofiction is defined by its engagement with different kinds of non-human—in this case the wide range of Australian species (both native and introduced) and habitats, and environmental phenomena such as flood, drought and bushfires that are particularly pertinent in an Australian context.

What also makes the exploration of these tropes uniquely Australian are the links drawn between environmental themes and Australian settler-coloniality in these texts. Some common tropes of Australian settler-colonial literature include the depiction of the domination of native habitats and their inhabitants, an emphasis on the settler-coloniser (whether as an early settler or a more contemporary form of non-Indigenous inhabitant) as a hero or heroine fighting for belonging in a place that is difficult to fully know or understand, and the marginalisation of Indigenous Australian characters. Other tropes also include a focus on settler-colonial human action and endeavour, with the non-human world rendered either as a threat to overcome or as a passive and agency-less background (see Carter; Gibson).

This paper does not focus on ecofiction broadly but rather a particular subset of this genre which adheres to the genre conventions of Australian crime fiction. Throughout the remainder of this paper, we will refer to this subset of Australian ecofiction as ‘Australian eco-crime fiction’. While it is of course not unusual for Australian crime texts to take place in Australian environments, we argue that there are many texts—notably many that have been published in the past decade—that engage with environmental themes that go beyond mere setting, as will be described below. The term ‘eco-crime’ may be partly misleading, though, and it is worth exploring this briefly here. ‘Eco-crime’ is often used to refer to crimes committed against or with some strong connection to the environment, such as oil spills, illegal logging, cases of animal cruelty, or the climate crisis itself as a crime facilitated by capitalist and settler-colonial systems of domination. Here, we use the term more broadly to also encapsulate crime fiction that depicts intra-human crimes that happen within the context of climate crisis—a crisis that has and will continue to exacerbate conflict, criminality and violence amongst humans as the impacts worsen (see Hsiang et al.; Ranson; Agnew).

As advanced by Rachel Fetherston in her work analysing non-human representation in Australian crime fiction, this genre has long depicted ‘the troubling relationship between intra-human violence and the treatment of the nonhuman’ (1). The connection between human crime and the more-than-human as elucidated in such texts speaks to the possibilities within such genre texts of speaking to audiences about environmental issues in broad and accessible ways (Fetherston 1). The texts chosen for this study, Jane Harper’s The Dry and Chris Hammer’s Scrublands, challenge some of the long-standing and problematic tropes that centralise the non-Indigenous Australian quest for assured place and control over an ‘unpredictable’ environment (Potter 2019). A notable consciousness amongst Australian ecofiction works published within the last ten to fifteen years highlights the threat of the climate crisis to Australian humans and non-humans by citing ecological devastation that is a result of the nation’s still largely colonial logic. Such a logic invokes the colonial claim to stolen Indigenous lands and waters and the resulting exploitation of these places through large-scale resource extraction, which can be linked to local ecological impacts as well as the climate crisis through associated carbon emissions. Relatedly, many Australian eco-crime texts in this same period diverge from the perspective of the Australian natural world as an unforgiving, alien place in need of taming by the colonisers, often depicting such a relationship as incredibly problematic or shifting this narrative to instead reflect a more nuanced connection between the settler-coloniser and surrounding habitats. At the same time, Harper and Hammer’s texts also perpetuate problematic, settler-colonial views of the natural environment, but they do this, as Fetherson argues elsewhere, ‘through the lens of drought as an ecological catastrophe’ (5-6). For this reason, we have identified Australian eco-crime fiction as a genre—or sub-genre of Australian ecofiction—that is worth investigating in terms of its potential to engage readers with ecological perspectives.

Reader Response and Ecocriticism

Whilst many scholars are critically engaging with environmental crises in various ways, there is the question of how lay readers are responding to the representation of environmental catastrophe in the texts that they read. James Procter argues that professional reading—as in that which takes place within the academy—can place ‘a distance between the effects of texts’ (190). We therefore believe it is important for researchers to investigate the potential impact that the reading of both environmental fiction and non-fiction has on readers outside of the academy.

Reader response methodology is a mode of literary studies practice that has long-strayed outside the lines of clear definition, neither falling within the practice of close-reading analysis, nor more empirical social science methodology that employs stricter selection processes and often vastly different study designs. For the sake of this paper, though, reader response methodology can be summarised by drawing on the work of Wolfgang Iser, who argues that ‘a text can only come to life when it is read, and if it is to be examined, it must therefore be studied through the eyes of the reader’ (4). Within the discipline of literary studies, there has been a move towards research that includes more empirical studies of reader response to texts; this is what many scholars deem the ‘empirical turn’. David S. Miall suggests that turning to ‘the empirical study of reading’ may allow for a better understanding of how reading processes function (293). In his words, the empirical turn represents ‘a serious commitment to the examination of reading and the testing of hypotheses about reading with real readers’ (307).

In addition to the empirical turn within literary studies, the aforementioned empirical ecocriticism is a similar field and one that has been rapidly developing in recent years. The reader response research discussed in this paper is a contribution to this burgeoning field due to its collection and analysis of qualitative data relating to environmental literature. Empirical ecocriticism is described by Matthew Schneider-Mayerson et al. as ‘an empirically grounded, interdisciplinary approach to environmental narrative’ (328). Many of the assumptions tested by those working within empirical ecocriticism stem from the ideas put forward by various ecocritics on the matter of environmental literature and its capacity to influence readers (Schneider-Mayerson, ‘Just as in the Book”?’ 2). As quoted by Malecki et al., Lawrence Buell contends that literature can further our ‘environmental imagination’ by engaging the reader ‘with [the] experience, suffering, [and] pain … of non-humans’.[3] Empirical ecocritics seek to test what might be termed this ‘assumption’ about the power of literature to influence readers’ environmental imaginations.

The reader response survey described in this paper was undertaken within the conceptual frameworks of the above schools of thought: reader response and empirical ecocriticism. Our study does not definitively answer the empirical ecocritical question of whether eco-crime fiction does or does not influence environmental attitudes, values or behaviours (primarily as we did not conduct a before/after study). What it does do, though, is examine the responses of readers to Australian eco-crime fiction with the aim of better understanding the ecological themes, motifs and perspectives that eco-crime readers are most drawn to, if any at all.

Methodology: Selected Texts and Reader Recruitment

This study called for participants who had read at least one of six selected works of Australian ecofiction. These were:

The Dry (2016) by Jane Harper;

Dyschronia (2018) by Jennifer Mills;

Scrublands (2018) by Chris Hammer;

Storyland (2017) by Catherine McKinnon;

The Swan Book (2013) by Alexis Wright;

and The World Without Us (2015) by Mireille Juchau.

Recruitment of study participants was achieved with the assistance of the Centre for Adult Education (CAE), Australian libraries, the authors’ personal and professional social media platforms, and scholarly organisations and networks. By sharing a URL that linked potential participants to an online Qualtrics survey, readers who had read one of the six texts of Australian ecofiction were targeted. Based on the advertising used for recruitment (‘Are you an avid reader of Australian fiction?’), these readers also identified as regular readers of Australian fiction. The group of survey participants discussed in this paper is limited to those who responded to the two crime texts—The Dry and Scrublands. This is because an overwhelming number of survey respondents (74.8 percent) chose to respond to one of these texts, meaning that most of the qualitative responses received through this survey are concerned with eco-crime fiction. We will henceforth refer to this group as the eco-crime reader group or eco-crime readers.

The Dry introduces us to Federal Police agent Aaron Falk, who returns to his drought-stricken hometown of Kiewarra to mourn the death of an old friend and his family, only to find that the alleged murder-suicide is more complicated than the locals believe. Scrublands tells the story of Martin Scarsden, a veteran journalist who visits the drought-stricken New South Wales town of Riversend in an attempt to tell the story of a mass shooting that occurred there one year prior, discovering that the real truth behind the shooting is yet to be uncovered.

Many of the organisations and channels through which participants were recruited were literary in nature. As could be predicted using Michelle Kelly et al.’s discussion of an Australian ‘reading class’, this method may have restricted this study to a certain kind of reader: those who typically read ‘“literary” fiction and “serious” non-fiction’ rather than genre fiction, and those who are often more engaged with broader literary consumption in Australia (for example, attending writing festivals, attending their own book group, and reading book reviews) (292). Investigating the reading practices and responses of this study’s participants is therefore mostly an exploration of crime fiction readers but also readers whose habits are not necessarily representative of more widespread Australian reading, based on the recruitment that took place through the CAE and because some participants also identified themselves as academics.[4]

It is also important to note that any conclusions we draw about readers’ feelings regarding the representation of the non-human in the selected texts of Australian ecofiction are based on responses that are possibly coming from readers who are already engaged with current ecological discourse in some way.

Methodology: Survey Questions

The reader response survey was undertaken by the self-selected participants, with additional questions concerning the text that each participant chose to respond to. Similarly to Schneider-Mayerson’s recruitment process in his study of North American climate fiction readers, participants had to describe their chosen text in their own words, without referring to online sources or the book’s blurb (see below) (‘The Influence of Climate Fiction’ 476). Participants were also asked to include a local postcode to confirm their Australian residency and select their age bracket to indicate that they were over 18 (the legal age of adulthood in Australia). Participants responded to a range of other demographic questions (such as age, gender, and education). The following open-ended discussion questions prompted participants to reflect on particular aspects of their chosen text. If participants answered ‘Yes’ to any of these questions, they were invited to explain their response further:

In 2–3 sentences, how would you describe this book? Please respond without consulting the book’s blurb or online sources.

Was there a particular lesson or message that you took away from your reading of this book? If yes, please describe what this lesson or message was. (Response options: Yes, No, I can’t remember)

Did the text’s portrayal of natural places make you feel a particular way? If yes, please describe this feeling. (Response options: Yes, No, I can’t remember)

Were there any particular descriptions of or events regarding animals, plants or natural places that prompted this feeling (as described in the previous question)? If yes, what were they? (Response options: Yes, No, I can’t remember)

Did the text’s portrayal of animals and their relationships with human characters resonate with you? If yes, please describe in what way. (Response options: Yes, No, I can’t remember)

Have you read other books of Australian fiction that made you feel a similar way? (These may or may not include other books on the list of six used in this study.) If yes, what are they and how did they make you feel a similar way? (Response options: Yes, No, I’m not sure)

Asking participants to recall particular descriptions in the text that relate to nature and the non-human allowed us to understand how Australian eco-crime texts may encourage the reader to interpret the narrative in certain, often personal, ways. However, it should be acknowledged that respondents in this study were asked to remember their selected text quite some time after they had originally read it; limitations in their ability to recall certain details therefore exist.

The phrasing used in some of the survey questions should also be noted here. In particular, the use of ‘natural places’ is a term that in hindsight should perhaps have been evaluated more closely prior to the survey being undertaken by participants. The reason for this relates to the key differences between conceptualisations of ‘nature’ and ‘place’. Place is inherently performative and is constituted through interventions and encounters of and between humans and non-humans. While the concept of ‘nature’ is well problematised in ecocritical scholarship, and is not a straightforward opposition to ‘culture’, the term is deployed here to reference non-human material agents that constitute environments, an agency that precedes human engagement. The concept of ‘natural places’ is thus potentially ambivalent. However, in the context of this survey it was deployed as alternative nomenclature for situated habitats or material environments.

While we will briefly acknowledge the demographic results of the participant group, most of our discussion focuses on the qualitative responses of participants to their chosen text; these responses have been analysed using a thematic coding approach (Robson 467). Participants’ responses were anonymous and selected quotes discussed here are reported verbatim with any identifying information removed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Reader profile

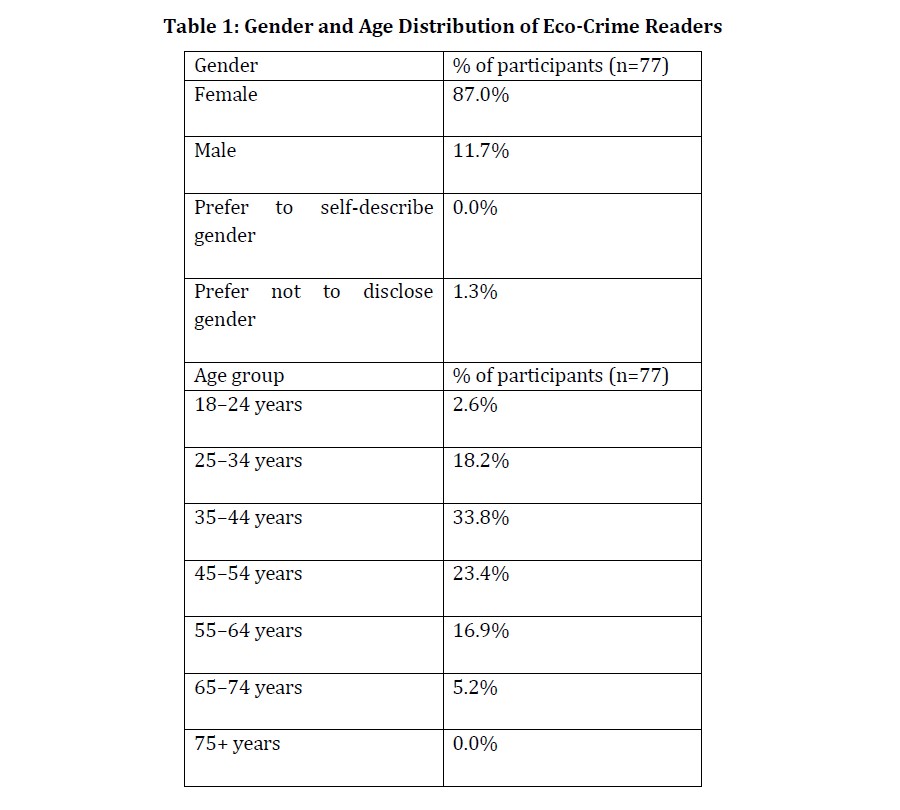

The eco-crime reader group primarily consisted of people who identified as female (87.0 percent) and were aged 35–44 (33.8 percent) and 45–54 years (23.4 percent) (Table 1). Participants were located across all Australian states and territories (with the exception of the Northern Territory) with the majority (63.6 percent) residing in the state of Victoria, which is most likely due to our recruitment strategy being focused in this state.[5] Most participants had either an undergraduate (41.6 percent) or postgraduate degree (52.0 percent) as their highest qualification, which fits with Kelly et al.’s description of those within the Australian reading class as typically possessing a tertiary education (292).

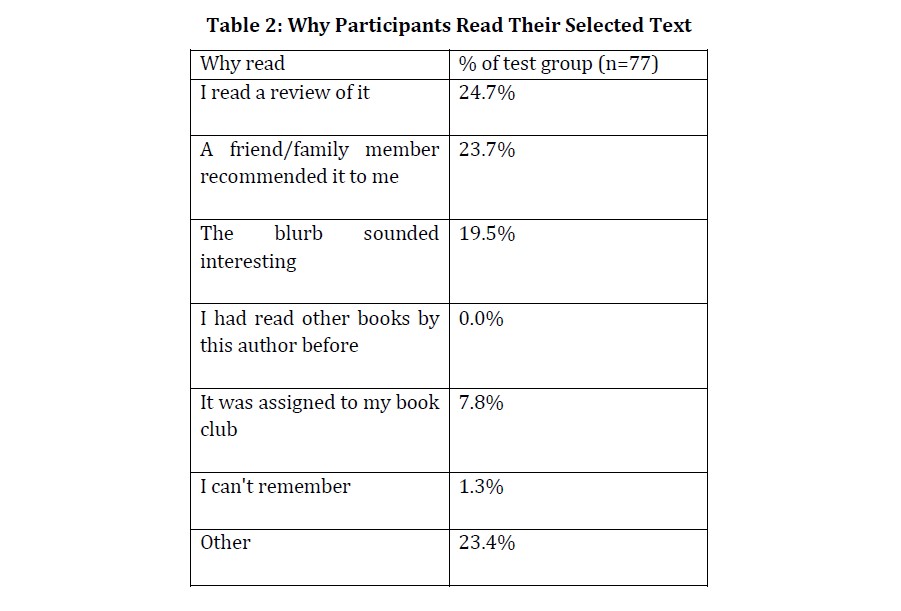

Many participants had read one of the study’s six texts because they had either read a review of it (24.7 percent) or a friend or family member had recommended it to them (23.4 percent) (Table 3). Most of the eco-crime readers selected The Dry as the text they had read and were responding to in the survey (87.0 percent), with the remaining eco-crime readers (13.0 percent) responding to Scrublands. This is perhaps not surprising given both the national and worldwide popularity of Harper’s text when compared to Scrublands.[6]

Response to the Representation of Natural Places

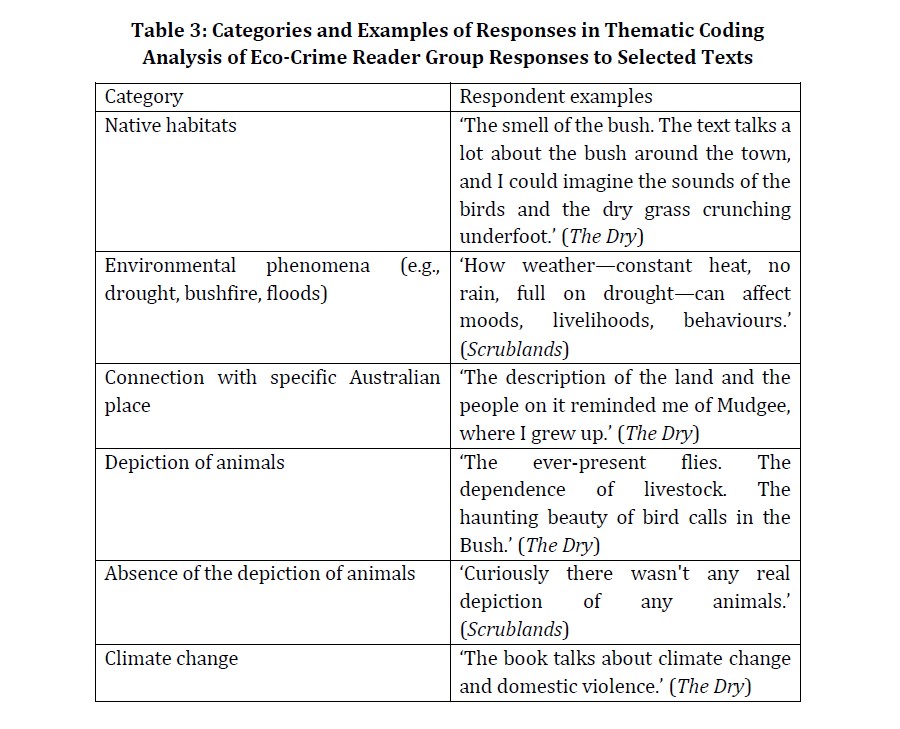

Now shifting focus to the qualitative responses to the text-specific questions asked of the surveyed readers, the results indicated that participants were most likely to respond to the question regarding the depiction of natural places in their selected text (‘Did the text’s portrayal of natural places make you feel a particular way?’). The places depicted in many of these texts can be defined as native Australian habitats, such as the bush, although many, such as the farming landscapes, may be viewed more as a product of human (and colonial) intervention than ‘natural’. This prevalence of place and habitat in participants’ responses was determined using thematic coding analysis of the answers that participants provided to the questions regarding their selected text (Table 3). Whether it was a native habitat such as the Australian bush or a colonial landscape such as a farm, these portrayals evoked strong responses from readers regarding their own relationships to place and how environmental phenomena such as flooding and drought can impact these places.

The affective component of attitudes was especially represented in readers’ responses, as many participants described how certain depictions of the non-human made them feel. As will be demonstrated by readers of The Dry, the stifling feeling pertaining to a drought-ridden, rural farming community was one of the most common reactions described by readers in this study, but some participants also commented on feelings of nostalgia regarding their own experiences of similar settings. For example, a communications director from Victoria described Harper’s depiction of the Australian landscape in The Dry as reminiscent of their ‘own experience of wheatbelt towns’. Similarly, an historian from New South Wales ‘found the description of the landscape and environment to be absolutely compelling and authentic. I’ve spent too much time in areas just as oppressive and stark’.

Despite the often-negative feelings towards the inhospitable setting of The Dry, some readers saw positives in Harper’s descriptions of country life. A public servant from Victoria reflected on how ‘it felt free and light to be reading a book set in the country. The space, the fresh air… reminded me of my childhood’. A communications advisor from New South Wales wrote that The Dry made them feel ‘inspired to spend more time in the country and proud of the landscapes we have in Australia’—a surprising response in many ways, given the violently tragic themes of the text and the tense political climate that often surrounds the issue of drought in Australia.[7] This response indicates that depictions of these altered landscapes and their relationship to surrounding non-human elements play a key role in engaging the reader with their own experience of place and various habitats in Australia.[8]

Thinking about the selected texts as ‘regionally specific’ (Schneider-Mayerson, ‘The Influence of Climate Fiction’ 488) is potentially a productive means of understanding the impacts of Australian eco-crime fiction. Some readers, such as a PhD student from Victoria, picked up on the geographical specificity of some of these texts, stating:

I think the strength of The Dry and the reason for its success is its depiction of a really specific Australian landscape and performative geography linked to that landscape and psyche. It’s not ‘quintessential’ Australia, and that’s why it works so well.

These varying descriptions of personal connection to place were also seen amongst respondents in Schneider-Mayerson’s study of climate fiction readers (‘The Influence of Climate Fiction’ 487), suggesting that a reader’s response to a text may relate strongly to the places where they have grown up, lived or even visited briefly. As Schneider-Mayerson emphasises in the context of climate fiction, the consideration of spatial distance is important:

We might conclude from this… that the geographical setting… matters a great deal, because it can capitalize on spatial proximity or potentially decrease spatial distance. Readers may be more likely to find diegetic events believable or ‘realistic’ if they identify with the work’s setting, which speaks to the value of regionally specific ecofiction. (‘The Influence of Climate Fiction’ 487-8)

Survey responses often emphasised either human place over nature in the text or the natural world over human place (in terms of which resonated with the participant most). For example, a sessional teacher from Victoria noted the depiction of ‘crops, livestock and people’ in The Dry, indicating that the agricultural environment of the text resonated with them strongly (although they also mention that the ‘dry’ nature of the land as a whole resonated strongly as well). Comparatively, a housewife from Victoria suggested that the sublimity of the described natural setting of The Dry was registered by readers as opposed to human place and environment; specifically, they emphasised ‘the rock tree’, ‘the cliff edge’ and ‘the dry river bed’ in their response.

As can be seen, some of these responses provide a generative starting point from which to consider the significance of habitat, and its entanglement in place. As discussed above, the relationship between ‘nature’ and ‘place’ is complex, and we see readers engagement with different ideas of ‘natural place’ as a particularly significant outcome of this study. Many readers of the eco-crime texts have understood the term ‘natural place’ as representative of native Australian habitats—like ‘the bush’—and/or more ‘built’ environments that are a product of settler-colonialism—like farming landscapes and rural townships. The relationship between these latter places and environmental phenomena such as drought, bushfire and flood perhaps explains this. These might be human—particularly settler-colonial—places that the readers are reflecting on, but they exist in relation to the ‘natural places’ and phenomena that surround and permeate them—drought, bushfire, and flood. Thus, some of the responses in this study are reflecting this complicated connection between place and ‘nature’, showing how readers perhaps felt invited to reflect on their own conceptualisations of place and nature, even if inadvertently, and consider the multiple possibilities of place and its relationship to the non-human.

This emphasis on both place and habitat in reader responses to texts such as The Dry relates to Alexis Weik von Mossner’s work on narrative environment and empathy. Using Ann Pancake’s Strange as This Weather Has Been (2007), Von Mossner examines how readers are encouraged to care about the endangered environment of the Appalachian Mountains through this text. Readers of Pancake’s text view the environment through multiple perspectives, which, according to Von Mossner, encourages an understanding of how the destruction of the mountain environment affects the families that rely on it (564). While Von Mossner’s rendering of diverse environmental perspectives and the potential impact its depiction has on readers’ beliefs, attitudes and actions is not explored in this study, it is nonetheless interesting that The Dry also addresses connections between rural labour and environmental crisis in a small and isolated community. It is possible that such a narrative might encourage greater awareness of the portrayed habitat and the people and non-humans that are impacted by its destruction.

Response to Environmental Phenomena

Another common theme in the eco-crime reader group’s text-specific responses was a reference to environmental phenomena such as drought, bushfire and flooding. Drought and fire both play a significant role in Harper’s narrative and seem to strongly shape the experience of the survey participants who read it. All of the novels in this study address these themes in a variety of ways and while The Dry may not overtly explore the impact of climate change in Australia, its striking portrayal of the ruinous impacts of drought and bushfire speaks volumes about the future reality of climate catastrophe for many Australians.

Many readers of this text commented on the significance of drought, its familiarity to Australians, and its overarching impact on rural Australian towns. One particularly striking response came from an editor in Victoria who described the following:

I find books that … describe the Australian landscape give me a yearning feeling. I love nature and enjoy imagining the descriptions in books but I’m particularly affected by well crafted Australian descriptions—e.g. Tim Winton, Jasper Jones and [The Dry]. I can hear sticks cracking under my feet, smell the wood smoke and feel the driving rain on my face.

Similarly, the sessional teacher from Victoria wrote the following:

There were frequent references to the dry land, described with reference to trees, roads, crops, livestock and people. The ‘dry’ theme was strong and impactful throughout. The parched natural landscape was a powerful component of the narrative.

These examples are just some of many that reflect on the depiction of drought and bushfire in these texts, with some participants—like the sessional teacher above—pondering how ‘the dry’ affects not only livestock and people, but trees and the broader ‘natural landscape’ as well.

The overall emphasis on drought in participants’ responses speaks to our own understanding of how non-human phenomena are utilised in the crime texts. The fact that many respondents focused on this element of the text but did not reflect on the depiction of individual non-humans is significant. We chose to include both The Dry and Scrublands in our research because of their striking portrayal of environmental phenomena; even though the depiction of animals in these texts is also important, the threat of drought and bushfire that permeates these novels is what we believe makes them interesting examples of Australian eco-crime fiction. The fact that so many readers of these same texts recognised the importance of phenomena like drought in The Dry and, to a lesser extent, Scrublands, validates this. Readers’ acknowledgements of these phenomena likely relate to the descriptions of heat and aridity that are so strongly represented in both texts in comparison to the isolated events involving individual non-humans, such as livestock and wildlife. Additionally, most Australian readers would be familiar with and have different attachments to the immersive experience of heat and so a significant response to heat’s representation in the texts is to be expected.

One response that struck us as particularly attuned to the ecological considerations of The Dry was one provided by the aforementioned housewife in Victoria who noted that

there was room for both the really breathtaking beauty of nature and a kind of fear of the unforgiving character of the natural world … Nature is very present, and so much bigger than the people, and unconcerned for them. Nature is kind of an alien other.

In some ways, this reflection evokes a partly ecocentric perspective in its suggestion that the non-human exists externally to the human, even if in devastating ways and even if said non-human phenomena, such as drought and bushfire, may be intensified by human actions. However, this participant’s assertion that the Australian non-human is ‘an alien other’ also exemplifies the still largely prevalent colonialist ideology of the Australian natural world as an other in need of control. Marcia Langton describes how Australian settler-colonial culture encourages ‘the dominion of civilisation over nature’ (16), and an understanding of nature as the other can result in an exacerbation of this dominion. Consequently, this reader’s interpretation of the text as demonstrating both complex human-non-human relations and an othering view of nature as ‘alien’ affirms that Harper’s text brings important perspectives on the cause-and-effect relationship between humans and non-humans to the fore, but also upholds problematic settler-colonial perspectives on nature and the non-human.

Response to the Representation of Non-human Animals

One of the most notable findings to come out of this study is how participants responded to the representation of non-human animals in these texts or, more specifically, how they did not respond. Only 11.7 percent of the eco-crime reader group described particular depictions of animals in their chosen texts. Whether they had read The Dry or Scrublands, the vast majority of readers did not reflect on the representation of non-human animals in these texts. This could perhaps be related to the fact that both eco-crime texts did not focus primarily on animals (although as discussed below, animals still play roles in the narratives) but could also indicate that readers are more likely to feel a connection to place than to particular species or individual non-humans.

Some readers did take the time to reflect on the fact that there was an absence of animals in their selected text. One participant, a software developer from Victoria who had read Scrublands, wrote that ‘Curiously there wasn’t any real depiction of any animals’. Hammer actually highlights in his narrative that animals (and plants) are few and far between in the drought-stricken landscape, describing how ‘the cattle yard is empty, of cattle and grass and any other living thing; even the flies have abandoned it’ (78). The text’s portrayal of a lack of non-human animals emphasises the harsh impacts of catastrophic drought in rural communities, in many ways drawing more attention to the plight of the non-human animal by highlighting their absence. As evidenced by the results of the study, though, readers—apart from the software developer above—did not feel a need to reflect on this absence in their responses, indicating that their attention was not drawn to this aspect of the novel.

It is also notable that very few participants specifically commented on the descriptions of animal cruelty in both crime texts. The Dry contains a confronting scene with a mutilated calf and Scrublands describes an equally brutal killing of a cat. The housewife from Victoria who had read The Dry stated that ‘every time there were animals in the story they were being misused by people: shooting rabbits, cruelly shearing sheep, the calf… that got its throat cut and left on… Falk’s doorstep’. A public library employee in Victoria referred to ‘the senseless killing of a cat [and] drought-affected stock’ in Scrublands. A retiree in Queensland who read Scrublands recalled the ‘dead animals’ mentioned throughout the novel and stated that such depictions revealed ‘how hard it was to be owners of livestock in dry times [and] how humans relate to animals in different ways including cruelty’. Apart from these responses, though, no other readers commented on the representation of animal cruelty in the crime texts. It is difficult to pinpoint why this might be, although the texts’ focus on intra-human crime and violence (and a less clear focus on non-human experiences) may be key here.

The other main focus of those few responses discussing the portrayal of animals was flies—both the animal and the general atmosphere suggested by their presence in a hot, rural Australian town. A marketing executive from Victoria who read The Dry wrote that ‘I have felt the suffocating heat and the flies that can only come from an Australian town’ and, when asked whether there were any particular narrative events regarding animals, plants or natural places that prompted this feeling, they simply responded with ‘The flies! The damn flies!!’ A research fellow from Victoria mentioned that ‘The ever-present flies’ in The Dry resonated with them, while a dental assistant in Queensland who also read Harper’s novel recalled ‘The opening scene of flies swarming over arid countryside and drawn to the bodies of the murdered family…’ This connection between flies and death in The Dry was also noted by a teacher from Victoria, who described how ‘the heat and flies at the funeral were visceral’. They are describing one of the early scenes of the text where, following the opening scene where the flies swarm the dead bodies of the Hadlers (the novel’s primary victims), a funeral is held for them in the drought-stricken town of Kiewarra where, unsurprisingly, flies are a common presence. This focus on flies, rather than other animal representations in these crime texts, is arguably aligned with the main focus of most of the eco-crime reader responses on place and environmental phenomena. That is, the flies are not ‘just’ animals in their own right, but are culturally construed to represent the supposed harshness of the land and the aridity of the Australian continent that Australian settlers—particularly farmers—need to survive. Harper and Hammer certainly uphold this settler-colonial perspective in their writing, although what makes their work distinct from others writing into the Australian settler literary tradition is their emphasis on conditions that are even more extreme than normal, alluding to the drastic impacts on Australian ways of life under climate crisis. The fact that readers primarily spoke of these flies is at least testament to the cultural capital that these insects hold in Australian society.

Conclusion

While further research is needed to better articulate what themes resonate with readers of Australian ecofiction, particularly those who may not be environmentally inclined, this study reveals that readers can experience strong feelings about the non-human as depicted in Australian eco-crime fiction, and that this non-human is likely to be drought, bushfire or other non-human phenomena. The fact that some participants shared personal memories of places in Australia whose landscapes and natural surroundings were represented in their selected text also demonstrates the role of relatability in reader response to environmental themes. Significantly, this finding emphasises the importance of local narratives if literature is to be an effective tool to encourage more environmental awareness and sympathetic behaviour. In particular, the reader responses in this study make clear that it is reader familiarity with, and memories of, particular environments which makes them powerfully evocative.

The qualitative responses to the representation of the non-human animal in the selected texts provide plenty of questions for future research. Why did so many readers not report strong feelings regarding the depictions of animals, especially in texts that involve some horrific scenes of animal cruelty? Do readers take more notice of setting and place than they do of non-human ‘characters’? Considering the particular influence of a popular genre fiction in this study, it is worth further investigating the role that popular genres play in affecting readers’ emotions in response to depicted environmental issues. As Schneider-Mayerson contends in a study examining readers of Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife (2015), a ‘pulpy, hard-boiled, and often violent thriller’ may appeal to a broad audience (‘“Just as in the Book”?’ 3). Harper’s The Dry—described by reviewer Janet Maslin as a ‘breathless page-turner’—is just that, but with a less direct focus on climate change. Further studies are necessary to establish whether texts like The Dry and Hammer’s Scrublands encourage a response in the reader regarding environmental issues more so than those texts that are considered to be literary, rather than genre, fiction.

One potentially restrictive element of eco-crime fiction in terms of its potential to engage readers with pro-environmental understandings is the dark and confronting atmosphere of most of these texts. Crime fiction by nature is grim. Add to this an emphasis on catastrophic ecological crises and the connections between such crises and violent crime, and there is a strong possibility that such texts may not do much to convince people that positive change is possible. It is significant that this hopelessness may actually be a deterrent for some readers to engage with climate action in the real world. Schneider-Mayerson reflects on this, arguing that readers’ intensely negative emotional responses to some climate fiction texts may not be particularly effective in persuading people to act on climate change (‘The Influence of Climate Fiction’ 489), and could actually result in ‘individualistic “prepping” instead of engaged citizenship or political mobilization’ (Peak Oil, cited in ‘The Influence of Climate Fiction’ 495). It would be interesting to further investigate whether eco-crime fiction set in the present day warrants similar reactions from readers as more dystopian, speculative climate fiction.

Given the international popularity of The Dry, future research could also investigate how non-Australian readers respond to the depiction of drought in this text—especially those who do not reside in places where drought or periods of hot, dry weather are considered the norm. Significantly, some texts of North American climate fiction have speculated on the future of states such as California and Nevada in the context of water shortages and drought. Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife and Clare Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus (2015) explore the potential impacts of climate change and water politics on a United States of the near future. Based on what we know about the eco-crime texts featured in our study, it is perhaps true that Australian authors are developing a similar kind of drought-focused genre in response to the climate emergency.

Acknowledgements

The reader study described in this paper was undertaken with ethics approval from Deakin University’s Human Ethics Advisory Group (HAE-19-012). The authors would also like to thank Matthew Schneider-Mayerson, Wojciech Malecki, Alexa Weik von Mossner and Frank Hakemulder for their valuable feedback on an earlier version of the reader study design.

Rachel Fetherston is an early career researcher in literary studies and the environmental humanities. Her research investigates the representation of the non-human in Australian ecofiction and the potential impact that such fiction has on the reader’s relationship with nature. This work includes considerations of speculative and science fiction, crime fiction, multispecies studies, and the intersection of reader response and nature connection. She is currently teaching across literature and the environmental humanities at the University of Melbourne, La Trobe University and Deakin University and is a co-founder of Remember The Wild, Australia’s first nature connection charity.

Emily Potter is Professor of Writing and Literature at Deakin University. Her research considers how imaginative and material socio-cultural practices and infrastructures shape environments and communities in a context of colonial legacies and environmental crisis. Emily’s most recent book is Writing Belonging at the Millennium: Notes from the Field of Settler Colonial Place. She is currently undertaking the ARC-funded project ‘Reading in the Mallee: the literary past and future of an Australian region’ (with Brigid Magner and Torika Bolatagici) and is the co-editor of the Journal of Australian Studies.

Kelly Miller is an Associate Professor and Environmental Social Scientist in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences at Deakin University, with over 20 years’ experience in Higher Education and a PhD in the Human Dimensions of Wildlife Conservation. Kelly’s work centres on the interface of human experience and nature, exploring if and how human values, attitudes and behaviours can align with global, national and local goals for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Kelly specialises in the human dimensions of wildlife conservation and management with major studies in wildlife and environmental value orientations, community attitudes toward threatened species conservation, urban wildlife management, wildlife-human conflict, environmental education, education for sustainability, and sustainable behaviours. With extensive experience in social research and community engagement, Kelly’s work has contributed to conservation planning and education for sustainability in Australia and internationally.

Devin Bowles is an epidemiologist and social scientist with a research focus on the socially-mediated health effects of climate change. He is a former board member of both the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Public Health Association of Australia. He is on the editorial board of Pedagogy in Health Promotion and is vice-president of the Benevolent Organisation for Development Health and Insight.

Notes

[1] As argued by John Frow, genres are categories bestowed by publishers, booksellers and consumers of books, rather than belonging innately to a text or set of texts (29–28).

[2] This includes depictions of the broader global impact of climate change, as well as the impacts specific to Australian locales.

[3] Lawrence Buell, Writing for an Endangered World: Literature, Culture, and Environment in the U.S. and Beyond (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001), 2, cited in Malecki et al., Human Minds and Animal Stories, 9.

[4] Many of these participants did not specify which academic discipline they worked within, so it cannot be assumed that these readers were necessarily scholarly readers working within literary studies.

[5] The CAE, one of the organisations that assisted with the recruitment process, is based in Victoria. However, it is worth noting that the primary academic organisation utilised for recruitment—the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, or ASAL—has networks across Australia, so recruitment of survey participants was by no means solely focused on the south-eastern states.

[6] For international reviews of Harper’s work, see Janet Maslin; Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore.

[7] For an overview of government responses to drought in Australia, see Karen Downing et al.

[8] These types of responses raise the question of how international readers have responded to these texts, particularly the internationally successful The Dry. There would be merit in a future study investigating the role that readers’ personal experiences of the places alluded to, or directly mentioned, in works of Australian eco-crime fiction has on their response to the text/s in question.

Works Cited

Agnew, Robert. ‘Dire Forecast: A Theoretical Model of the Impact of Climate Change on Crime.’ Theoretical Criminology 16.1 (2012): 21-42.

Bacigalupi, Paolo. The Water Knife. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015.

Carter, Paul. The Lie of the Land. London: Faber and Faber, 1996.

Downing, Karen, Rebecca Jones and Blake Singley. ‘Handout or Hand-up: Ongoing Tensions in the Long History of Government Response to Drought in Australia.’ Australian Journal of Politics and History 62.2 (2016): 186-202.

Fetherston, Rachel. ‘“Little Difference between a Carcass and a Corpse”: Ecological Crises, the Nonhuman and Settler-Colonial Culpability in Australian Crime Fiction.’ Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature 21.2 (2021): 1-17.

Frow, John. Genre. Milton Park, Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxon: Routledge, 2006.

Gibson, Ross. South of the West: Postcolonialism and the Narrative Construction of Australia. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1992.

Guillory, John. ‘The Ethical Practice of Modernity: The Example of Reading.’ The Turn to Ethics. Ed. Marjorie Garber, Beatrice Hanssen and Rebecca L. Walkowitz. New York: Routledge, 2000. 29-46.

Hamby, Anne, David Brinberg, and James Jaccard. ‘A Conceptual Framework of Narrative Persuasion.’ Journal of Media Psychology 30.3 (2018): 113-24.

Hammer, Chris. Scrublands. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2018.

Harper, Jane. The Dry. Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia, 2016.

Hsiang, Solomon M., Marshall Burke and Edward Miguel. ‘Quantifying the Influence of Climate on Human Conflict.’ Science 341.6151 (2013): 1212.

Iser, Wolfgang. Prospecting: From Reader Response to Literary Anthropology. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins UP, 1989.

Juchau, Mireille. The World Without Us. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015.

Kelly, Michelle, Modesto Gayo and David Carter. ‘Rare Books? The Divided Field of Reading and Book Culture in Contemporary Australia.’ Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 32. 3 (2018): 282-95.

Langton, Marcia. ‘What Do We Mean by Wilderness?: Wilderness and Terra Nullius in Australian Art [Address to The Sydney Institute on 12 October 1995].’ The Sydney Papers 8.1 (1996): 10-31.

Malecki, Wojciech, Piotr Sorokowski, Boguslaw Pawlowski and Marcin Cieński. Human Minds and Animal Stories: How Narratives Make Us Care About Other Species. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Maslin, Janet. ‘“The Dry”, a Page-Turner of a Mystery Set in Parched Australia.’ The New York Times 9 January 2017. <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/09/books/review-dry-jane-harper.html>. 11 Mar. 2022.

McKinnon, Catherine. Storyland. Sydney: HarperCollins, 2017.

Miall, David S. ‘Empirical Approaches to Studying Literary Readers: The State of the Discipline.’ Book History 9.1 (2006): 291-311.

Mills, Jennifer. Dyschronia. Sydney: Picador, 2018.

Pancake, Ann. Strange as This Weather Has Been. Emeryville: Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007.

Potter, Emily. Writing Belonging at the Millenium: Notes from the Field on Settler-Colonial Place. Bristol: Intellect Books, 2019.

Procter, James. ‘Reading, Taste and Postcolonial Studies.’ Interventions 11.2 (2009): 180-98.

Ranson, Matthew. ‘Crime, Weather, and Climate Change.’ Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 67.3 (2014): 274-302.

Robson, Colin. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods. Oxford: Blackwell, 2011.

Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew. ‘The Influence of Climate Fiction: An Empirical Survey of Readers.’ Environmental Humanities 10.2 (2018): 473-500.

—. ‘“Just as in the Book”? The Influence of Literature on Readers’ Awareness of Climate Justice and Perception of Climate Migrants.’ ISLE 27.2 (2020): 337-64.

—. Peak Oil: Apocalyptic Environmentalism and Libertarian Political Culture. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2015.

Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew, Alexa Weik von Mossner and W.P. Malecki. ‘Empirical Ecocriticism: Environmental Texts and Empirical Methods.’ ISLE 27.2 (2020): 327-36.

Sebag-Montefiore, Clarissa. ‘Horror in the Outback: Jane Harper, Charlotte Wood and the Landscape of Fear.’ The Guardian 19 October 2016. <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/oct/19/horror-in-the-outback-jane-harper-charlotte-wood-and-the-landscape-of-fear>. 11 Mar. 2022.

Von Mossner, Alexa Weik. ‘Why We Care about (Non)Fictional Places: Empathy, Character and Narrative Environment.’ Poetics Today 40.3 (2019): 559-77.

Watkins, Claire Vaye. Gold Fame Citrus. New York: Riverhead Books, 2015.

Wright, Alexis. The Swan Book. Artarmon: Giramondo Publishing Company, 2013.