By Agata Mrva-Montoya, Maggie Nolan and Rebekah Ward

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version. doi: 10.56449/14408765

Even within the humanities, the discipline of English is unusually diverse in both its object of study, and its approaches and methodologies. It has multiple subfields and frequently aligns with other disciplines including creative writing, cultural studies, and theatre/screen studies. As Ronan McDonald explains:

A typical department of English … might include one faculty member working on a research-funded project with colleagues from the sciences on neurological dimensions to narrative, another researching the philology of Icelandic quest narratives, another working on performativity and gender in relation to contemporary urban street theater, and another working on neglected social histories of Jacobean chapbooks. All these projects are informed by diverse agendas and methods and would provide widely different accounts of their raison d’être. (3)

The porousness of its disciplinary identity is what makes English studies so compelling. However, this openness may also make it difficult to survive let alone flourish in the metric-driven rankings culture that currently dominates the academy, and which frequently determines institutional priorities as well as the flow of funding. Moreover, in the Australian context, waves of restructures have seen many English departments folded into larger institutional entities with which they are more or less aligned.

Despite these challenges, Australia-based English academics have continued to publish in numerous outlets on a diverse range of topics, as all scholars in Australia have long been expected to. The nature of that pressure, however, has not remained static. In the 20th century, the focus was on the ‘publish or perish’ adage, generating a culture of quantity over quality. The federal government of the 1990s used the DEST (Department of Education, Science and Training) scheme (later Higher Education Research Data Collection [HERDC]) to assign research funding based on publication volume. In the competitive landscape of the 21st century, the focus has shifted to the quality of outputs, driven by the increasing importance of global university rankings. Not surprisingly, and in spite of widespread recognition that global rankings distort both the agendas and research of universities, the use of citation metrics and journal rankings has expanded in importance and complexity.

The proliferation of journal rankings using citation data has produced a large body of scholarship that examines, and often critiques, such systems of research evaluation. Amongst this scholarship, there is a consensus that rankings are problematic and often unreliable, particularly for the humanities (Ochsner et al., ‘The Future’; Pontille and Torny). The citation-based metrics have poor coverage of books, which remain important for the humanities scholars (Thelwall and Delgado). Moreover, while in the sciences there is a strong correlation between citation counts and peer review quality score, this is not necessarily the case in humanities where ‘citation counts are likely to be, at best, a weak indicator of scholarly impact in the arts and humanities’ (Thelwall and Delgado 825).

Despite the recognition of their shortcomings, journal rankings influence scholarly publishing, and are implicitly or explicitly used by institutions to make decisions about staff promotions and workloads (Mrva-Montoya and Luca). The present study, commissioned by the Australian University Heads of English (AUHE), a peak body comprising academics from more than 30 universities, used an online questionnaire to investigate how journal rankings are being used by tertiary institutions within the discipline of English, and what the impacts of these rankings are on English academics at various careers stages and institutions.

This article begins with a brief overview of the scholarship on journal rankings in the humanities. We then present quantitative and qualitative data from the online questionnaire before examining the institutional policies, the types of journal rankings used, and their impact on the publishing decisions, research areas and academic careers in the discipline of English. We conclude with a discussion of the usefulness and impacts of journal rankings in the discipline of English in Australia.

Journal Rankings in the Australian Context

Australia was relatively slow to adopt journal rankings, but in 2007 the Australian Research Council (ARC) formed the Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA). As part of this exercise, discipline-based panels allocated some 21,000 academic journals into four tiers based on quality: A* (top 5% of papers), A (next 15%), B (next 30%) and C (final 50%). Those tiers were used as a proxy to assess the quality of individual articles. Following a consultation period, that frequently involved various scholarly associations lobbying the ARC on behalf of their own journals, the initial list was revised and released again in 2010. Although some academics saw the ratings as an improvement to the previous quantity-based approach, the scheme also attracted significant criticism, with many suggesting it would produce considerable and unwelcome changes to the research environment it sought to measure (Bennett et al.; Cooper and Poletti; Genoni and Haddow; Vanclay).

The key criticisms of the ERA-ranked journal lists echo existing scholarship on the problematic nature of journal rankings for the humanities. Of particular concern was the assumption that a consistent definition of quality could be reasonably applied across the breadth of scholarly research. Yet Vanclay found significant and inequitable differences in the ratings. Not all fields, even those within the same broad discipline area, follow the same bell-curve and some fields do not have any top-ranked journals. Even expert-based evaluation, though considered superior to metric-based measures, is not free from bias, and is associated with the scholar’s personal knowledge and experience with a journal (East).

That is not to say that a positive correlation between journal and article quality is impossible. In a study of a similar Italian scheme, Bonaccorsi et al. found a ‘positive relationship among peer evaluation and journal ranking’, interpreting that as ‘evidence that journal ratings are good predicators of article quality’ (Bonaccorsi et al.). However, this was not the case in Australia, with several discipline-specific studies finding little correlation between ERA ratings and other assessments of quality (Genoni and Haddow). Generally speaking, bibliometric and scientometric methods remain problematic for the humanities (Hammarfelt and Haddow; Ochsner). Humanities scholars are concerned about quantification, the application of assessment methods developed for the sciences, and their negative impact on the diversity of research, particularly in emerging fields, disciplines and associated journals (Ochsner et al., ‘Four Types’). For many scholars in the humanities who undertook research on Australian topics the ERA’s privileging of the ‘international’ as indicative of higher quality has been frustrating.

In the face of such concerns, the ARC abandoned journal rankings in 2011, much to the relief of many academics. Since that time, however, as Mrva-Montoya and Luca found, rankings, including the discarded ERA list, survive at the institutional level with implicit pressure to publish in outlets considered to be high ranking or prestigious. Additionally, many Australian universities pivoted to global rankings performance evaluation tools which have even less relevance to the Australian context. The global uptake of similar systems has generated widespread concern about the impacts on academic careers. For example, the 2012 Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) and the Leiden Manifesto of 2015 (Hicks et al.) both recommend that journal rankings should not be used to evaluate individual researchers. Even studies of the Italian scheme, which has been found to be relatively accurate in terms of journal/article quality, warn against using ratings to assess individuals, noting that it should only be used as part of aggregate evaluation (Bonaccorsi et al.; Ferrara and Bonaccorsi). Yet, as mentioned earlier, there is evidence that the ERA scheme, which was considerably less rigorous than the Italian equivalent, was used by institutions to make decisions about staff recruitment, promotion, and workload allocations (Mrva-Montoya and Luca).

Concerns about the negative impact of current research assessments in Australia are well grounded. The ERA scheme fed institutional pressure for academics to publish in top-ranked journals, irrespective of where the research was best suited, and this pressure has continued in different forms and plays out variously across the country. Hughes and Bennett found that academics were increasingly selecting publication outlets based on ‘maximising externally assessed performance’ (such as rankings) rather than publishing in journals that would reach the most relevant audience for their research, even though respondents acknowledged the system was flawed (347). The system has not only impacted the diversity of publishing options, but also narrowed academic freedoms, redirecting attention towards fields with more top-ranked journals. This is particularly apparent for early career researchers (ECRs) who tend to be more responsive to institutional demands and need to publish in top-ranked journals for career advancement, while more senior researchers were better placed to rebel by resisting pressure to publish in particular outlets (Hughes and Bennett). At the same time, ECRs also need to publish quickly, while they negotiate the intricacies of the ranking system and peer review from the position of limited power and little experience (Merga et al.; Mrva-Montoya, ‘Book Publishing’).

Scholars of English literature in a country such as Australia face additional challenges in a globalised ranking culture. As Genoni and Haddow argued in 2009 in the wake of Australia’s defunct ERA exercise, local ranking systems that privilege ‘international’ journals inevitably disadvantage journals with local, regional, or national focus and readerships. Their research indicated that journals ‘originating in middle ranking countries in terms of research production’ are under-represented in the citation indexes used to calculate metrics, further disadvantaging researchers in the fields of Australian literature and literary cultures, for whom publishing in Australian literary journals is frequently most appropriate. The pressure to publish with international outlets deemed prestigious, without ‘paying attention to the disciplinary fit, the target audience and the motivations of the author’ (Mrva-Montoya, ‘Strategic Monograph Publishing’ 12), clearly disadvantages scholars working on Australian literature.

In the face of such pressures, many Australian literary scholars responded by enthusiastically participating in the transnational turn in literary studies which produced some significant scholarly outcomes in the early 21st century. As Osborne, Smith and Morrison observe, however, such strategies risk reproducing the values of the globalised ranking machine and further marginalising literary scholarship on Australian Indigenous, migrant and emerging writers and threaten the very future of certain fields and subfields, including those that are fundamental to national self-understanding (see Nolan, Mrva-Montoya and Ward).

Introducing Our Study and Its Respondents

In order to explore these general findings, we carried out a research project about the impact of journal rankings on publishing strategies and academic careers. It targeted academics who teach and research in the discipline of English at all Australian universities. The online questionnaire included a combination of closed-ended questions, enabling subsequent quantitative analysis of results, and open-ended questions, providing opportunities for respondents to elaborate and provide detailed qualitative responses. The questionnaire, created using Qualtrics, was anonymous but captured demographic information about the type of university with which the respondent was affiliated, their specific research subfield, their career stage, gender, and employment status. This information helped us to understand whether individuals within the same discipline face different publishing pressures and/or are afforded different opportunities depending on the type of universities they are employed at, such as the Group of Eight (research-intensive universities) versus other universities (especially those in regional Australia), the structural disadvantages at work in the application of journal ranking systems, and how these play out across the sector.

The online questionnaire was tested on a small sample of English researchers before being disseminated via AUHE email lists and social media. This broad but purposive distribution strategy was designed to gather responses from across the spectrum of English staff, allowing valid and valuable conclusions to be drawn from the study. Respondents volunteered to participate and were asked to provide informed consent at the start of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was available for two months between 13 December 2021 and 25 February 2022. The quantitative data was analysed using a combination of SPSS and Excel, while qualitative data was thematically coded in Microsoft Word.

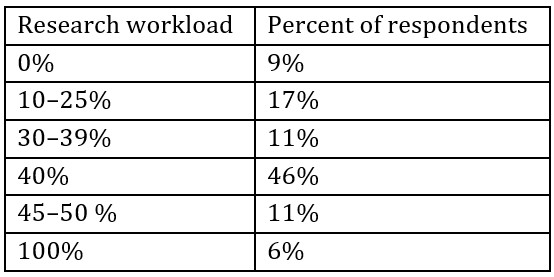

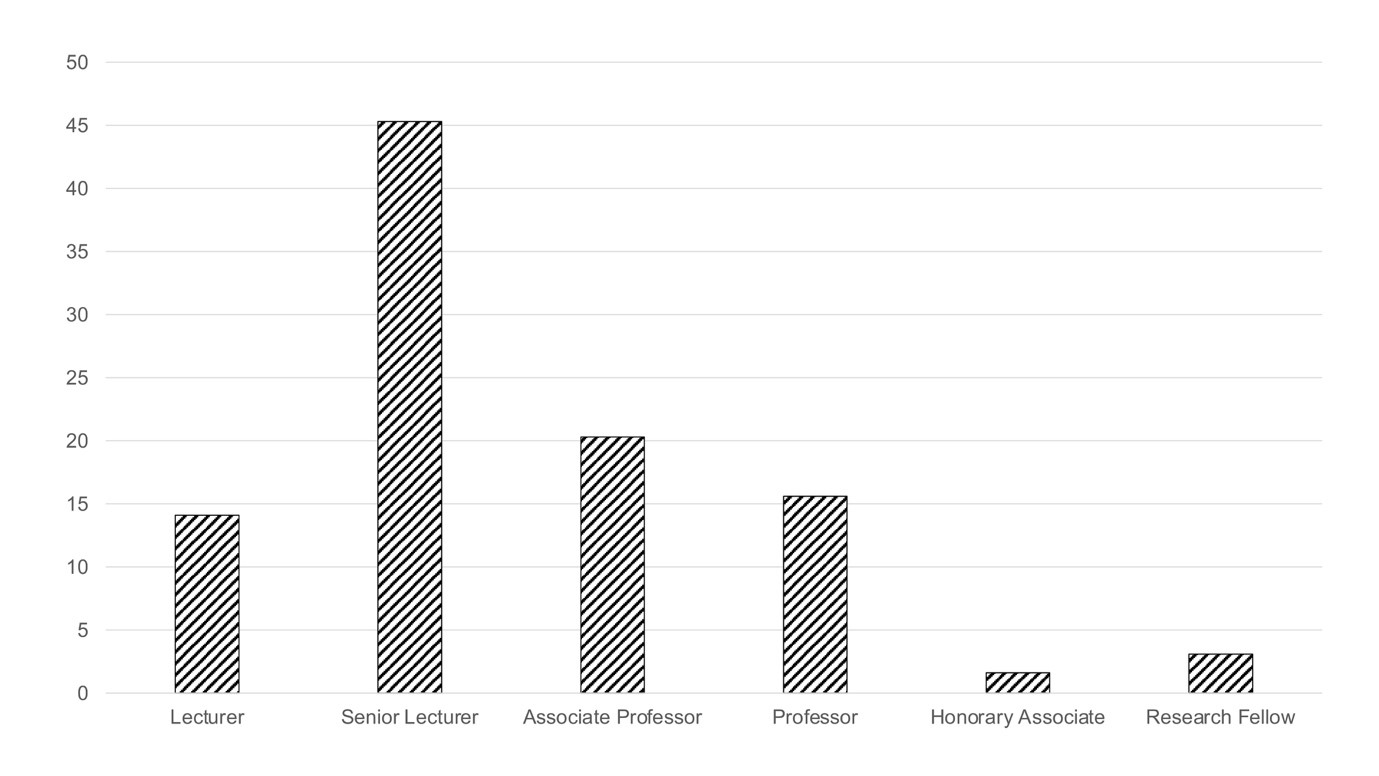

We received 68 valid responses to the online questionnaire, with 64 responding to most demographic questions (unless marked otherwise). It is difficult to determine what percentage of academics undertaking teaching and research in English studies in Australia participated in the questionnaire. Almost all Australian universities offer some literary or English studies, but not all offer a full program or major, with some offering English literature as part of creative writing or teacher education programs. Moreover, some academics work across more than one field and/or program and it is not uncommon for smaller universities to only have a single member of staff overseeing English studies. We are confident, however, that with 68 respondents, the responses are fairly representative of the experience of English academics in Australia. The respondents were aged between 30 and 70 years old, with an average of 48 years old and a median of 47 years. No respondent identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, and only 16% (n = 63) identified as culturally and/or linguistically diverse (with a further 5% preferring not to answer this question). Overall, senior lecturers were the most represented group (45%) followed by associate professors (20%), professors (16%) and lecturers (14%) [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents in different roles.

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents in different roles.

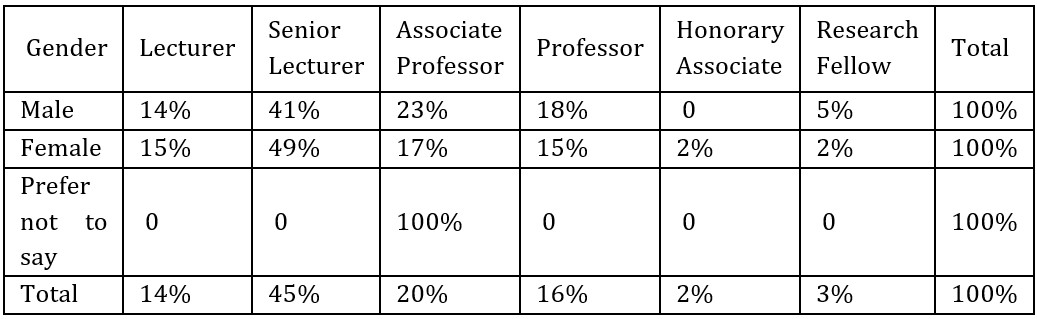

The majority of respondents are in continuing full-time positions (86%), another 9% have full-time contracts, while 3% are on part-time contracts and 2% are sessional. The workload allocation is quite diverse though the conventional 40/40/20 workload model (40% teaching, 40% research, and 20% administration) was the most common (47%) [Table 1]. Not every respondent with lower research workload has greater teaching commitments, as some carry a substantial service allocation. Some were in research-only or teaching-only roles.

Table 1: Percentage of respondents with different research workload allocations.

While overall there were more women among the respondents (64%) than men (34%), men are more likely to occupy higher positions at universities [Table 2].

Table 2: Correlation between gender and seniority.

The largest cohort of respondents came from the Group of Eight (GO8) universities (47%), (not surprising given their larger numbers) followed by universities that are not members of any groupings (28%). Next 11% work in organisations that are members of Innovative Research Universities Australia (IRUA), 8% in the New Generation Universities (NGU) and 6% in the Australian Technology Network of Universities (ATN). As some universities are members of multiple groupings, we also asked about location; 30% of respondents came from regional universities. The respondents (n = 62) represented a variety of research areas within the discipline of English and most respondents reported working across multiple subfields in English. Indeed, respondents identified 42 disparate research areas, with Australian literature (n = 16) and creative writing (n = 8) mentioned most often.

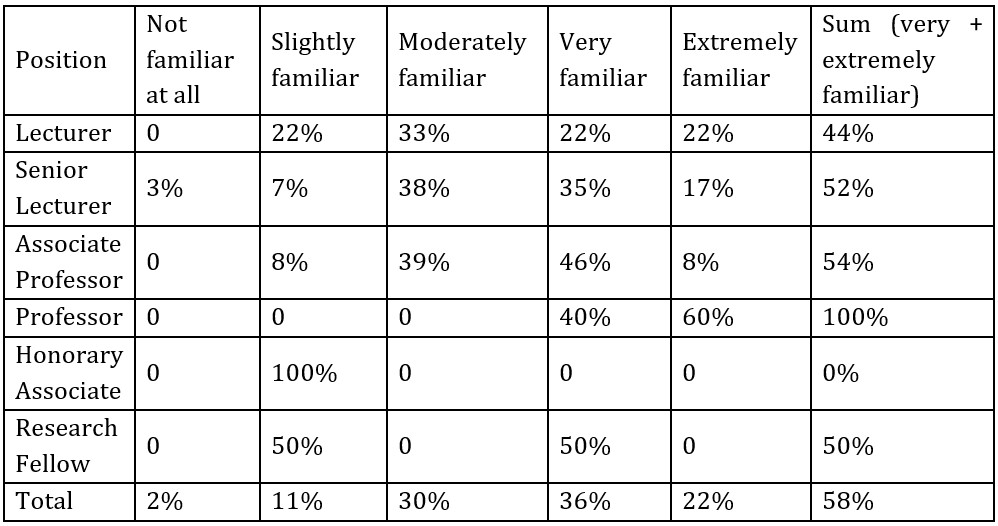

Overall, the respondents are relatively familiar with journal ranking systems and their career implications, with 58% reporting that they are very or extremely familiar, and another 30% as moderately familiar [Table 3]. There is a degree of correlation between the position and level of familiarity with professors reporting the highest confidence in understanding the system.

Table 3: Correlation between seniority and familiarity with journal ranking systems.

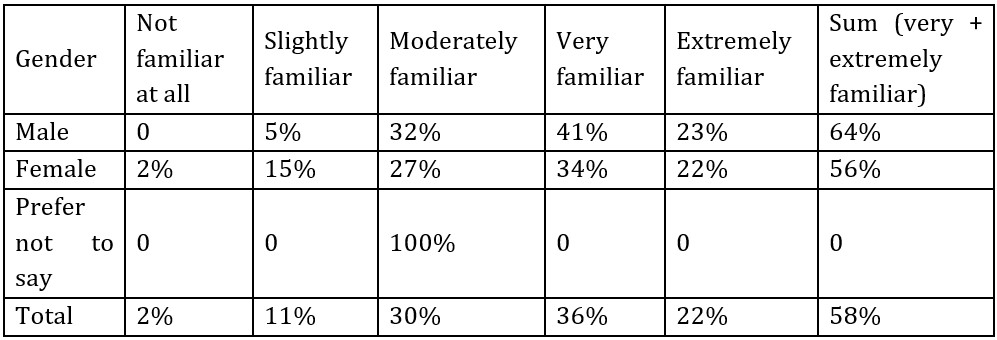

Interestingly, male respondents seem to be slightly more familiar overall with journal ranking systems, which corelates with the greater percentage of men found in more senior positions [Table 4].

Table 4: Correlation between gender and familiarity with journal ranking systems.

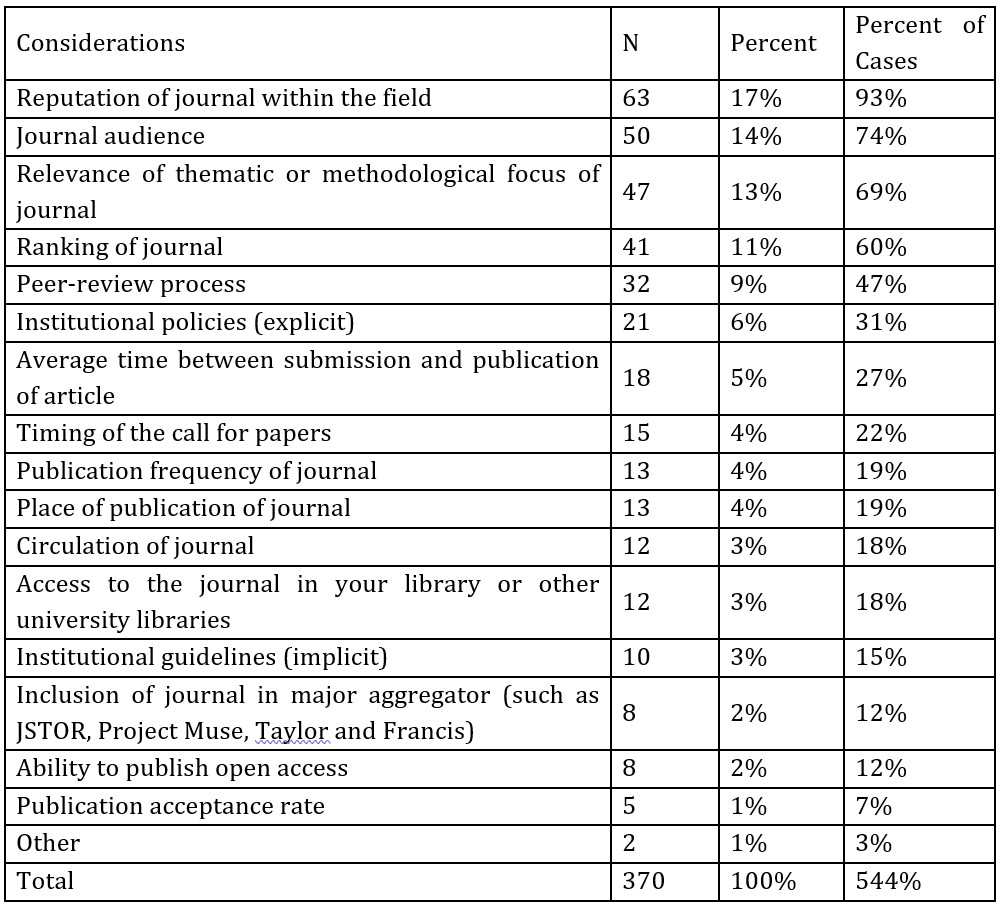

We asked respondents about the top five considerations impacting the choice of journal when publishing academic articles including journal reputation within the field (selected by 93% of respondents), its audience, its thematical and methodological relevance, its ranking and peer review process [Table 5].

Table 5: Considerations impacting respondents’ choice of journals.

The Use of Journal Rankings and Their Impacts

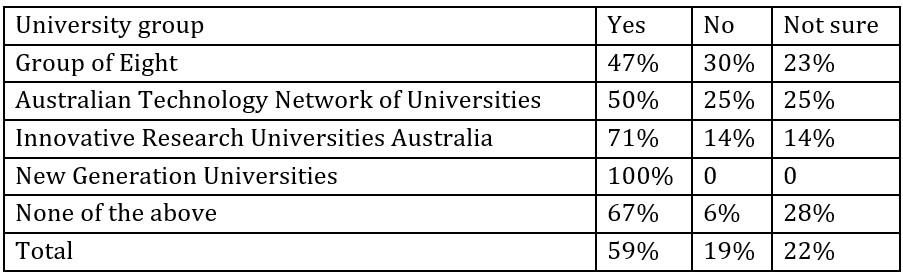

If journal rankings are indeed a clear and objective measure of quality, one would expect that such systems would be both pervasive and similar across the sector. But this does not seem to be the case. Although almost 60% of respondents (n = 67) reported that their university had specific policies, guidelines or mandates about preferred publishing outlets, 18% of respondents said no, and 22% weren’t sure [Table 6].

Table 6: Percentage of respondents reporting the presence of specific policies, guidelines or mandates in various university groupings.

GO8 universities are somewhat less likely to have specific policies, guidelines or mandates in contrast to the newer universities, especially those that are members of IRUA and NGU or respondents from regional universities, 68% of whom reported the presence of a range of institutional directives. Forty respondents provided more information about the various requirements used at their university. The most commonly used directives (n = 18) stipulate the use of Scimago, Scopus Q1 or the defunct ERA ranking of journals. These directives vary from encouraged to required, and from subtle to blatant in their implementation, and are often associated with clear rewards for doing so, including larger research workload allocations and enhanced chance of promotion. The second most reported approaches (n = 12) employed an institutional journal ranking system, associated with questionable value and often with a lack of transparency. Such bespoke journal lists, created internally by institutions and which combine modified Scimago and Scopus rankings and other idiosyncratic decisions, are frequently seen to be the worst of both worlds. Several respondents mentioned lack of transparency and the disciplinary bias against humanities, a concern associated with research assessments more broadly. As one respondent reported, ‘Unfortunately, the university’s bespoke literature journal ranking list is a short hodge-podge of scholarly outlets, apparently assembled at random’. Another respondent wrote:

In addition to mandating Scopus as the main landmark for quality, Faculty has its own a list of journals that is supposed to indicate quality but this is made up of journals nominated by individual school programs so it is extraordinarily biased towards the journals nominated by the people appointed by our Head of School to sit on the School’s Research committee.

At one university the lists are ‘a product of the old, repudiated 2011 ERA list + new additions volunteered by academics during a specific call about 3 years ago’. Fewer respondents (n = 9) mentioned a non-specified (or otherwise unclear) system of ranking journals, as well as a list of preferred book publishers (n = 4) and the fact that articles were preferred to books (n = 4). Only one respondent referred to an open access policy.

We were keen to understand how journal ranking systems in different universities came about and the responses were telling. These various approaches have been usually developed by management (n = 17), with limited consultation (n = 18). In some cases, consultation was ignored or dismissed (n = 12), or there was no consultation at all (n = 8). Many discipline-based scholars reported attempts to influence the process, including with jointly authored submissions, most of which fell on deaf ears. As one academic wrote, ‘My efforts to understand the literature journal ranking list—and to consider attempting to intervene in it—have been stymied by a general lack of understanding of its history, its structure, and its utility’. Organisational units responsible for these directives and lists included research units, school research committees, or deans and associate deans research at the faculty level, and outcomes differ depending on the institutional location of the discipline. As one respondent commented, ‘consultations do occur but are not usually heeded by management most at home in the sciences and unable or unwilling to take differentiated and nuanced approaches to humanities work’. The disciplinary bias against humanities was noted by another four respondents. According to one of them, ‘These policies seem to have been developed by STEM disciplines, and left to Humanities leadership to haggle over the details (and not always satisfactorily)’. Only five respondents, all from unclassified, regional institutions, reported staff have been consulted. In the words of one of them, this happened on a program-by-program basis: ‘In 2017, or thereabouts, the English program was asked to produce a document on accepted and best practices in publication. The regular reviews of the institution’s journal list include staff feedback.’

Overall, our respondents perceived journal rankings as an unnecessary and/or problematic exercise (n = 10). As one commented, ‘They are a very imprecise measure of “quality” and should be abandoned’. Another wrote in a similar vein, that a:

[c]entrally generated list, disputed by disciplines, minor adjustments made, [is] still a very blunt instrument for measuring quality when the quality of individual publications and/or journals ought to be assessed at annual performance reviews instead.

And yet another stated, ‘It’s another form of punitive metrification. Makes it easier to cull staff, keep us docile, and slowly erode humanities publishing’.

Academics’ views on the impacts of journal rankings on subfields and interdisciplinary research tended to be shared. Consistent with concerns outlined earlier about the impacts of globalised rankings on nationally focused research, seven respondents noted the negative impact on local journals, publishing culture and ‘national literature’, one of whom pointed out that ‘journal rankings also seem to favour publications owned by multinational corporations’, and ‘serve the interests of the multinational publishers who own many of the highly ranked journals, and help to stifle innovation and competition’. They also ‘dissuad[e] us from writing for the natural audience for our scholarship’. Several academics (n = 5) mentioned the ‘disastrous’ impact on subfields, including the subfield of Australian literary studies, and ‘the unintended consequence of marginalising certain areas of research’. Moreover, ‘journal rankings are self-reinforcing, ossify research culture, and militate against disciplinary change’. Another respondent pointed out that ‘journal rankings militate against the interdisciplinarity and exploratory research that our institutions simultaneously require of us; it’s worth publishing elsewhere and broadening horizons’.

Of most concern, though, were the inequities both within and between institutions that such directives seem to exacerbate. Mrva-Montoya and Luca found that ‘less research-intensive universities actually put greater pressure on their faculty to publish in particular ways, or they were more transparent about doing so, likely because these smaller universities wanted to improve their standing’ (81), and this study confirmed these findings. While 60% of respondents reported their university had specific policies, guidelines or mandates about preferred publishing outlets, these were slightly less common in GO8 universities in comparison to less research-intensive and/or regional universities. A number of respondents pointed out the inequity of the system (n = 6) and impact on staff (especially casual academics and ECRS) (n = 4). As one of them wrote:

Being able to pay attention to journal rankings, to target highly ranked journals and build demonstrable impact seems like luxuries of continuing careers. Insecure staff, increasingly comprising the majority of academic teaching staff, are often happy to get anything published as it can be so hard to make this happen. Journal rankings therefore feel like another cog in a system that reinforces inequity and privilege, dividing the academic community between career and casual academics.

Such institutional approaches also impact junior and sessional academics and more established or continuing academics differently, but some academics are working to ameliorate these inequities. As one respondent wrote ‘now that I have some traction, I use my powers/reputation (such as they are) to publish in interesting places, to support small journals with work that can be published open access, and to support students and early career researchers with opportunities’.

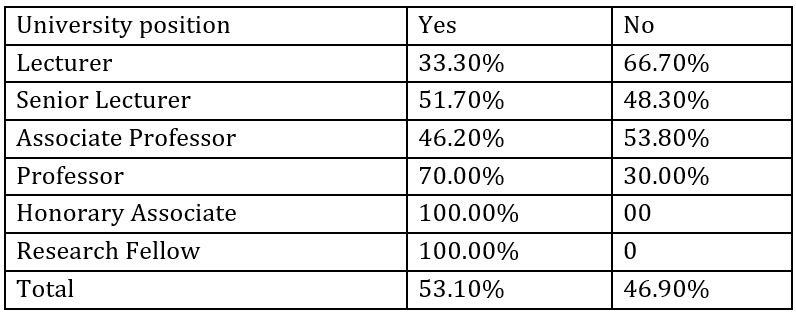

Similarly, the consequences for not publishing in an institution’s preferred outlets were experienced differentially as well. While 53% of respondents (n = 67) reported being personally impacted by journal ranking systems, surprisingly, the gender breakdown shows more male (59%) than female (49%) academics feeling the impact, and more senior academics over junior [Table 7], findings which require further investigation.

Table 7: Correlation between seniority and reported feeling of being personally impacted by journal rankings.

These findings contradict previous studies in which early career researchers are seen as having less autonomy, but understanding the connection between research evaluation and employability better (Hughes and Bennett; Merga et al.). Gender disparity was not noted in the Mrva-Montoya and Luca study, and can potentially be linked with the greater awareness of the implications of journal rankings and a more strategic approach to careers among male and more senior academics. Similarly, research shows some female academics are ‘ambivalent about seeking promotion’, while others ‘lack the necessary information and are unsure about the qualifications and skills required’ (Bagilhole and White).

The perception of impact of the institutional directives is stronger among colleagues from less research-intensive universities, especially those working in New Generation Universities, which can exacerbate existing inequalities across the discipline. There was some correlation between the feeling of being impacted and the type of university, with 47% of respondents at the GO8 universities feeling personally impacted, in contrast to 50% of respondents from the ATN, 57% from the IRUA and 80% from the NGU. The percentage was also higher than the average among respondents from regional universities (58%). This is consistent with findings from Mrva-Montoya and Luca’s study, which noted greater pressure to comply with specific requirements at the non-GO8 universities, suggesting structural inequalities across the sector. Moreover, the current study also confirmed the ongoing presence of the defunct ERA list of journals in research assessment policies. The prevalence of Scimago and Scopus Q1 journal rankings in those policies is also concerning, given that prior research shows the use of metric-driven methods in the humanities is problematic.

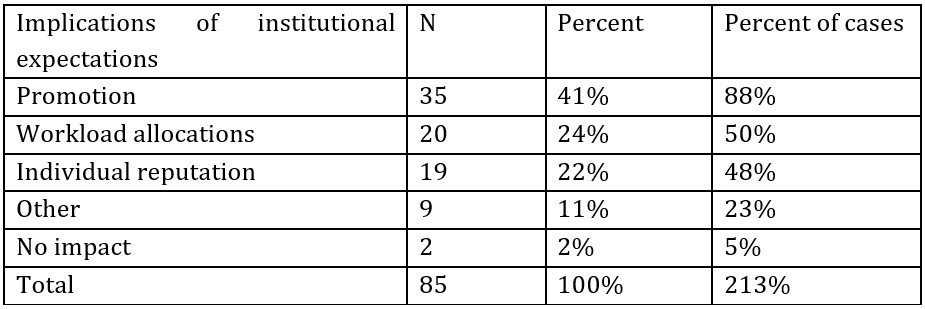

We asked about implications for publishing or not publishing in the institution’s preferred outlets. These are most frequently felt at key stage of academic careers, such as job interviews, annual performance reviews and promotion applications, but also workload allocation. Academics are also concerned about the impact of such systems on their reputation [Table 8]. Other issues mentioned included grant support, eligibility for sabbatical, and performance review in general.

Table 8: Frequency of the various types of implications of institutional expectations.

Those respondents who elected to elaborate on the impact of the journal ranking system on their careers (n = 35) pointed to annual performance reviews, promotion applications and job interviews (n = 15), usually with negative outcomes although two respondents had benefited from this model. As one of them wrote, ‘Publishing in highly ranked journals has enhanced my research record, grant success and broader publishing opportunities and outcomes’. While conforming to changing institutional directives clearly has its benefits, the capacity to do so is unevenly distributed and, in general, academics who publish in outlets deemed ‘inappropriate’ can be, and are, penalised with increased teaching load, further restricting capacity to research and publish quality work.

For many academics, journal rankings systems are determining decisions they make, not only about where they publish, but what they publish. One respondent said they were ‘choos[ing] journals and sometimes even topics with an eye to institutional requirements’, and another prioritising ‘publishing in journals with high impact factors and rankings over those which are most respected in the field’. Other academics reported prioritising journal articles over books and resorting to publishing more interdisciplinary work in science journals such as Nature, Letters and Current Anthropology. As we’ve noted, colleagues working in Australian literary studies are particularly disadvantaged. As one respondent wrote:

we have no highly ranked journals, which does impact my ability to contribute to my university’s ERA ranking (which is of some importance in a research-intensive institution), and also implicitly impacts how the quality of my research is regarded within the university.

Another similarly commented that ‘my research has not been taken as seriously as I like to publish in Australian literary journals’. The perception of publishing in low-ranking journals leads to ‘sub-standard ratings in annual performance reviews’, and ‘self-doubt and anxiety about research planning’. Some reported prioritising journal articles over books, a more traditional marker of prestige, and others resorted to changing subfields and publishing more interdisciplinary or collaborative work in order to comply with institutional expectations.

So, is there a place for journal rankings and lists? While some respondents see the value in having an informal discipline-based list of reputable journals, the creation of yet another ranking is perilous. One academic commented that: ‘Journal rankings are very important but work best as an informal measure, not something imposed by the university, which renders them rigid and possibly erroneous, as well as regionally dependent.’ Another one wrote:

I am not opposed to having some kind of indication of journal quality and ranking. I think that currently humanities and social science journals are not well served by the SJR [Scimago Journal and Country Rank] ranking list and SCOPUS … I think as well that there should be more acknowledgement of national journals, as I know that Australian literary journals do not do well on the current lists. The lists, as they stand, benefit scholars who can publish in generalist journals.

It became clear that any attempt to produce a journal list for the discipline of English would be fraught, partly because of the diversity of the discipline we alluded to at the beginning of this article. We asked respondents to list what they considered to be the top three most highly regarded journals in their area of research. We then collated all the journals listed under each rank, first into three lists and then into a single one. In total, the 67 respondents suggested 93 unique journal titles as the ‘top’ three journals in their specialty, with the most frequently mentioned journal ranked as number 1 by eight respondents, as number 2 by three respondents and as number 3 by another four respondents. In total, the three most frequently mentioned journals were listed by 15, 14 and 12 respondents, the fourth one by only seven respondents, with 59 journals mentioned only once.

Considering the diversity of research fields, this is not surprising. This large number of distinct journals demonstrate how problematic the creation of lists is even within a single discipline. As one respondent wrote, ‘English literature studies is too diverse a field, and too intersectional a field … to only recognise a small group of ranked journals as appropriate publication forums’.

For our participants, journal reputation within the field was the most important consideration when deciding where to publish a journal article. While it is not clear what all respondents mean by reputation, there was a strong sense that individual academics should be ‘trusted to choose [their] own publishing outlets, based on factors such as the audience and the reputation of the journal, instead of feeling coerced into publishing with journals that are not of [their] own choosing’. An individual researcher should have the ‘right to design and execute a research career, based on passion, interest, and expertise’. In the light of this, it is interesting to note that recent findings from the Ithaka S+R US Faculty Survey 2021 show that in the USA ‘Faculty are according less importance to a journal’s impact factor when deciding where to publish their scholarly research’ (Blankstein). The journal’s relevance and high readership were listed as the top characteristics followed by the journal’s ‘high impact factor or an excellent academic reputation’ across humanities and other areas (Bagilhole and White).

Conclusion

The ‘typical’ respondent to our questionnaire is a senior lecturer, female, of Anglo-Saxon background, who is 47 years old and working full-time in a 40/40/20 role at a GO8 university. She is researching across various subfields within the discipline of English and considers herself to be relatively familiar with journal ranking systems and their implications. But not as familiar as her male, usually more senior, colleagues. Consistent with the gender inequity in academic employment at universities in Australia, but also the UK and USA (Probert), there were more men than women at the professorial level among the respondents. The under-representation of women in senior roles has been linked with limited opportunities for promotion and professional development, ‘different treatment’ and ‘a difficult organisational culture, stemming from gendered organisational practices within universities’ (Bagilhole and White). The lack of cultural diversity among respondents is noteworthy.

Many academics in the discipline of English working at Australian universities are expected to comply with institutional policies, guidelines and/or mandates, which use various journal rankings as a proxy for quality. This is in spite of the fact that extensive research demonstrates that such rankings are problematic when used to evaluate individual researchers, particularly in the humanities. The journal rankings used in institutional mandates include the defunct ERA list of journals, metric-based Scimago and Scopus Q1 rankings, and other internally created lists. Such directives were typically developed using top-down approaches with limited or no consultation and without transparency, and have been associated with the disciplinary bias against humanities. In institutions in which academics were consulted about these directives, the lists are considered fairer and less punitive. Less research-intensive and/or regional universities are more likely to have such rules in place and put greater pressure on their staff to comply compared to GO8. While there is a degree of overlap between policies, guidelines or mandates, these terms mean different things. We didn’t distinguish between them in the questionnaire, which is a limitation of the study. That said, the distinction is not always clear, even within universities, and we can infer from the free-text responses that the GO8 universities are more likely to use informal guidelines, while in other universities more prescriptive mandates are in place. In contrast to previous studies, senior academics reported being more personally impacted by journal rankings than their junior colleagues, and male academics more than female. This is a surprising finding and requires further research.

While there may be some value in producing a discipline-specific journal ranking, it seems to us that any such attempt would be counterproductive. It is hard to see how any ranking system would not exacerbate the issues we’ve identified. It would also perpetuate research assessment systems which ‘systematically marginalise knowledge from certain regions and subjects’ (Chavarro and Ràfols; Chavarro et al.). Ironically, in the Australian context, Australian literary studies, and the local publishing programs that support it, are most vulnerable. At a time when academic research is expected to deliver national benefits, and in the context of a new national cultural policy, this outcome seems particularly perverse. In our view, it would be more strategic for the discipline to focus on educating its members and the broader academic community about the shortcomings of journal rankings and limitations of metrics in the discipline of English, and advocate to universities and the government for fair and rational processes of research assessment, which avoid one-size-fits-all policy instruments, recognise disciplinary conventions and follow clear and transparent quality criteria.

We are writing at time when there seems to be an appetite for review and change for Higher Education on the part of the Federal Government. On 30 August 2022 the recently appointed Minister for Education, the Hon Jason Clare MP, announced a ‘pause’ on the Excellence in Research in Australia (ERA) and the Engagement and Impact Assessment (EI) Exercise for 2023 pending a review of the objectives of the exercise, its operating model and the future (Australian Government, Review; Clare). The subsequent Review, Trusting Australia’s Ability, was released in April 2023 and recommended that the ERA, along with the ARC’s Engagement and Impact assessment, be discontinued. One its most strident recommendations was to not replace ERA and EI with a ‘metrics-based exercise because of the evidence that such metrics can be biased or inherently flawed in the absence of expert review and interpretation’ (Sheil et al). The Shiel review, as it has become known, wants to see cooperation between the ARC and the university regulatory body TEQSA (Tertiary Education and Quality Standards Agency) in developing a framework for research quality and impact. This signals a major shift in the role the ARC plays in auditing for research quality.

The review also addressed questions of ministerial interference that had disproportionately impacted the discipline of English, making the ARC more independent and objective (see Lamond). In so doing, the review addressed the decline of both the ARC’s autonomy and the erosion of trust in the ARC (to which the abandoned ERA journal ranking exercise no doubt contributed). In August 2023 the Australian Government released a response to the review that agreed or agreed in principle with all the recommendations, which was welcomed by universities and academics alike.

At the same time, the Minister initiated an Australian Universities Accord to build a plan for the future of Australian Higher Education. The final report was released in February 2024 and shows a strong focus on access and equity (as required by the terms of reference). It also touches upon questions of research evaluation, highlighting the need for improving the measurement of the quality and impact of Australian research including by ‘tak[ing] advantage of advances in in artificial intelligence, particularly natural language understanding, and data science to develop a “light touch”, automated metrics-based research quality assessment system’ (Australian Government 217). We await, with some trepidation, the flow-on effects of any new models on the institutional research performance policies and mandates, particularly for the humanities.

Much remains unknown. What we do know is that the evaluation of research quality and engagement and impact will continue in some form, and that it will likely be both data-driven and deploy peer review. What all this means for the future of journal rankings, let alone the discipline of English, remains to be seen, but now is a good time for academics in the discipline to continue to make their voices heard. It is clear that the individual careers of literary academics at different places and at different stages have been profoundly and differentially impacted by journal rankings. So too has the field of English studies, and particularly Australian literary studies. What is heartening, though, is that in February 2023 the federal government released a new National Cultural Policy—Revive—with a clear focus on the importance of national storytelling. Its subtitle is ‘a place for every story and a story for every place’ and scholars of Australian literary studies have the opportunity to remind governments and universities of the key role they play in ensuring that these stories continue to find a place in the national literary tradition. More broadly, we hope that this article contributes to the conversation about the discipline of English and draws attention to the impacts of research evaluation mechanisms that may well prevent it from flourishing.

Acknowledgements

We thank the respondents to our questionnaire for their time and insights. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Australian Catholic University (2021-260E).

Funding

This project was supported by the Australian University Head of English.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Dr Agata Mrva-Montoya is a lecturer in Media and Communications at the University of Sydney. She has published on the impact of digital technologies and new business models on scholarly communication and the book publishing industry. Her research explores how innovation, digital technologies, and power dynamics shape the publishing industry, with a focus on inclusive publishing and accessibility.

Maggie Nolan is an Associate Professor of Digital Cultural Heritage in the School of Communication and Arts at the University of Queensland. She is also the Director of AustLit, the Australian literary bibliographical database. She has published on representations of race and reconciliation in contemporary Australian literature, contemporary Indigenous literatures, literary imposture, and literary value. She currently holds an ARC Discovery grant on Irishness in Australian literature with Ronan McDonald (University of Melbourne) and Katherine Bode (ANU).

Rebekah Ward has recently completed her PhD in book history at Western Sydney University. Her research focuses on the history of print culture, blending traditional archival research with digital humanities approaches. Her doctorate explored how Angus & Robertson (the largest Australian publishing house) solicited book reviews from around the world on a mass scale in order to promote their publications.

Works Cited

Australian Government. Review of the Australian Research Council Act 2001. 2022. <https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education/review-australian-research-council-act-2001>.

Australian Government. National Cultural Policy—Revive: A Place for Every Story, a Story for Every Place. February 2023. <https://www.arts.gov.au/publications/national-cultural-policy-revive-place-every-story-story-every-place>.

Australian Government. Australian Universities Accord: Final Report. 2024. <https://www.education.gov.au/australian-universities-accord/resources/final-report>.

Bagilhole, Barbara, and Kate White. ‘The Context.’ Generation and Gender in Academia Ed. Barbara Bagilhole and Kate White. Basingstoke, UK; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. 3-20.

Bennett, Dawn, Paul Genoni and Gaby Haddow. ‘FoR Codes Pendulum: Publishing Choices within Australian Research Assessment.’ Australian Universities Review 2 (2011): 88-98.

Blankstein, Melissa. ‘Ithaka S+R US Faculty Survey 2021.’ Ithaka S+R. 14 July 2022. <https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/ithaka-sr-us-faculty-survey-2021/>.

Bonaccorsi, Andrea, Tindaro Cicero, Antonia Ferrara and Marco Malgarini. ‘Journal Ratings as Predicators of Articles Quality in Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences: An Analysis Based on the Italian Research Evaluation Exercise.’ F1000Research 4.196 (2015): 1-19.

Chavarro, Diego, and Ismael Ràfols. ‘Research Assessments Based on Journal Rankings Systematically Marginalise Knowledge from Certain Regions and Subjects.’ 30 October 2017. LSE Impact Blog. <https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2017/10/30/research-assessments-based-on-journal-rankings-systematically-marginalise-knowledge-from-certain-regions-and-subjects/>.

Chavarro, Diego, Puay Tang and Ismael Ràfols. ‘Why Researchers Publish in Non-mainstream Journals: Training, Knowledge Bridging and Gap-filling.’ Research Policy 46.9 (2017): 1666-80.

Cooper, Simon, and Anna Poletti. ‘The New ERA of Journal Ranking: The Consequences of Australia’s Fraught Encounter with “Quality”.’ Australian Universities Review 53.1 (2011): 57-65.

Clare, Jason. ‘Statement of Expectations 2022.’ Australian Government, Australian Research Council. <https://www.arc.gov.au/about-arc/our-organisation/statement-expectations-2022>.

Declaration on Research Assessment. San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment. <https://sfdora.org/read/>.

East, John. ‘Ranking Journals in the Humanities: An Australian Case Study. Australian Academic and Research Libraries 37.1 (2006): 3-16.

Ferrara, Antonia, and Andrea Bonaccorsi. ‘How Robust Is Journal Rating in Humanities and Social Sciences? Evidence from a Large-scale, Multi-method Exercise.’ Research Evaluation 25.3 (2016): 279-91.

Genoni, Paul, and Gaby Haddow. ‘ERA and the Ranking of Australian Humanities Journals.’ Australian Humanities Review 46 (2009): 7-26.

Hammarfelt, Björn, and Gaby Haddow. ‘Conflicting Measures and Values: How Humanities Scholars in Australia and Sweden Use and React to Bibliometric Indicators.’ Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 69.7 (2018): 924-35.

Hicks, Diana, Paul Wouters, Ludo Waltman, Sarah de Rijcke and Ismael Ràfols. ‘Bibliometrics: The Leiden Manifesto for Research Metrics.’ Nature 520 (2015): 429-31.

Hughes, Michael, and Dawn Bennett. ‘Survival Skills: The Impact of Change and the ERA on Australian Researchers.’ Higher Education Research and Development 32.3 (2013): 340-54.

Lamond, Julieanne. ‘Ministerial Interference is an Attack on Academic Freedom and Australia’s Literary Culture.’ The Conversation 4 January 2022. <https://theconversation.com/ministerial-interference-is-an-attack-on-academic-freedom-and-australias-literary-culture-174329>.

McDonald, Ronan, ed. The Values of Literary Studies: Critical Institutions, Scholarly Agendas. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2015.

Merga, Margaret K., Shannon Mason and Julia Morris. ‘Early Career Experiences of Navigating Journal Article Publication: Lessons Learned Using an Autoethnographic Approach.’ Learned Publishing 31.4 (2018): 381-9.

Mrva-Montoya, Agata. ‘Book Publishing in the Humanities and Social Sciences in Australia, Part Two: Author Motivation, Audience, and Publishing Knowledge.’ Journal of Scholarly Publishing 52.3 (2021): 173-89.

Mrva-Montoya, Agata. ‘Strategic Monograph Publishing in the Humanities and Social Sciences in Australia.’ Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association 70.4 (2021): 375-90.

Mrva-Montoya, Agata, and Edward J. Luca. ‘Book Publishing in the Humanities and Social Sciences in Australia, Part One: Understanding Institutional Pressures and the Funding Context.’ Journal of Scholarly Publishing 52.2 (2021): 67-87.

Nolan, Maggie, Agata Mrva-Montoya and Rebekah Ward. ‘“It’s Best to Leave this Constructive Ambiguity in Place!”: The Evaluation of Research in Literary Studies.’ Australian Literary Studies 38.2 (2023). <https://doi.org/10.20314/als.8ec9216602>.

Ochsner, Michael. ‘Bibliometrics in the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences. Handbook Bibliometrics. Ed. Rafael Ball. Munich: De Gruyter Saur, 2021. 117-24.

Ochsner, Michael, Sven E. Hug and Hans-Dieter Daniel. ‘Four Types of Research in the Humanities: Setting the Stage for Research Quality Criteria in the Humanities.’ Research Evaluation 22.2 (2013): 79-92.

Ochsner, Michael, Sven E. Hug and Ioana Galleron. ‘The Future of Research Assessment in the Humanities: Bottom-up Assessment Procedures.’ Palgrave Communications 3.1 (2017): 1-12.

Osborne, Roger, Ellen Smith and Fiona Morrison. ‘What Counts? Mapping Field and Value in Australian Literary Studies: The JASAL Case Study.’ Unpublished conference paper. ASAL Conference 2023.

Pontille, David, and Didier Torny. ‘The Controversial Policies of Journal Ratings: Evaluating Social Sciences and Humanities.’ Research Evaluation 19.5 (2010): 347-60.

Probert, Belinda. ‘“I Just Couldn’t Fit It In”: Gender and Unequal Outcomes in Academic Careers.’ Gender, Work and Organization 12.1 (2005): 50-72.

Sheil, Margaret, Susan Dodds and Mark Hutchinson. Trusting Australia’s Ability: Review of the Australian Research Council Act 2001. Australian Government, 2023. <https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-reviews-and-consultations/resources/trusting-australias-ability-review-australian-research-council-act-2001>.

Thelwall, Mike and Maria M. Delgado. ‘Arts and Humanities Research Evaluation: No Metrics Please, Just Data.’ Journal of Documentation 71. 4 (2015): 817-33, 825.

Vanclay, Jerome. ‘An Evaluation of the Australian Research Council’s Journal Ranking.’ Journal of Informetrics 5.2 (2011): 265-74.