By Jeremy Tsuei

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version. doi: 10.56449/14624296

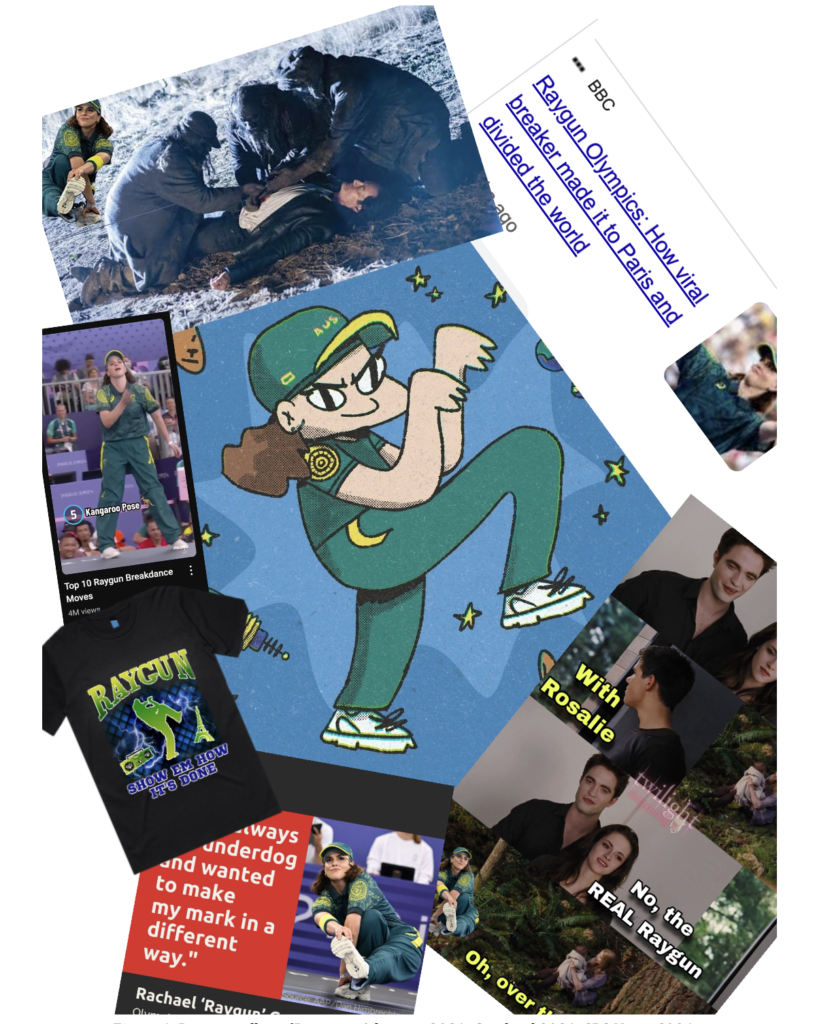

During the Paris 2024 Olympics, the first to feature competitive breakdancing, or ‘breaking’, as an Olympic sport, Australian female breaker Dr Rachael Gunn (otherwise known as b-girl Raygun) performed a routine which failed to attract any competitive points yet became an internet obsession. In an Olympics already making headlines due to online ‘culture wars’, the responses to Raygun were particularly polarised (Tocci; Stewart; Doyle). It seemed like everyone—from family members on Facebook, to TikTok influencers, to Reddit conspiracy theorists, to American comedian Jimmy Fallon and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese—had a fresh take on Raygun (The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon; Convery and Cox). Generally, critics took issue with her academic platform, the opacity of the Australian Olympic Committee’s (‘AOC’) selection process, and apparent taking of opportunities from other breakers, while defenders embraced her dedication, adherence to the Australian principle of ‘having a go’, creativity, and distinctiveness. For critics and embracers alike, vacillating between earnest and ironic, there was one aspect that all had in common: the agreement that Raygun was worth discussing—at a level of fervent insistence comparable perhaps to Raygun’s own dancing.

Figure 1. Raygun collage (Beetoota Advocate 2024; Cowland 2024; SBS News 2024; @MovedOnNotice 2024; Turnbull and Rodd 2024; WatchMojo 2024; Wood 2020)

Figure 1. Raygun collage (Beetoota Advocate 2024; Cowland 2024; SBS News 2024; @MovedOnNotice 2024; Turnbull and Rodd 2024; WatchMojo 2024; Wood 2020)

Approximately a decade prior, Sianne Ngai presented three aesthetic categories for understanding ‘how aesthetic experience has been transformed by the hypercommodified, information-saturated, performance-driven conditions of late capitalism’: cute, interesting, and zany (Our Aesthetic Categories 1). I argue that the Raygun moment pressures Ngai’s aesthetic categories and their claims to exclusive and everyday application, and specifically heralds an eclipse of the zany.

Particularly, the image of Raygun’s frenetic performance—literally on the floor, dancing under the clock and desperately competing for points, representing her country, and showcasing or somehow proving the focus of her academic career to the world—seems to exemplify Ngai’s description of the ‘unusually beset’ zany agent locked into a ‘desperate playfulness’:

In contrast to the rational coolness of the interesting, the discursive aesthetic of nonstop acting or doing that is zaniness is hot: hot under the collar, hot and bothered, hot to trot. […] [T]hese idioms underscore zaniness’s uniqueness as the only aesthetic category in our repertoire about a strenuous relation to playing that seems to be on a deeper level about work. (Our Aesthetic Categories 235, 7)

Yet Raygun is also many other things: cringe, larrikin, icon. These are general and culturally specific affects which zany is less equipped to capture, yet all describe and explore different and valid aesthetic responses to Raygun. I contend that Raygun pressures Ngai’s aesthetic categories because through this example they are not entirely undone or overridden; rather, Raygun signals a point or opportunity for evolution—one which Ngai also pre-empts in her own writing when she refers to zany as an ‘profoundly ambiguous or unstable’ category (Our Aesthetic Categories 231). By the ‘eclipse of the zany’, I suggest the zany has been obscured, but it remains to be seen by what, and if it will somehow re-emerge.

When We Talk about Raygun…

I have so far been begging the question of what ‘Raygun’ refers to—the performance or the responses. I suggest that ‘Raygun’ (whether in this analysis or in general communication) enfolds both and neither and refers to the inchoate storm of mediated internet artifacts: a large, chaotic, and digitally tangible and malleable mass. In the spirt of Ngai, who refers to ‘not only specific subjective capacities’ but also ‘the larger social arrangements these ways of relating presuppose’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 11), it is not an isolated episode or phenomenon, but the aesthetic takeup, reproduction, and gradual substitution in reaction to a stimulus.

Like the vast majority of Raygun commentators, I have not personally or directly witnessed Raygun’s breaking, only the myriad reaction videos, compilations, and edits available online. In Australia, the closest most can get to watching Raygun directly is through the 9Now streaming service, but even this is mediated through an app, a personalised profile, a commercial channel, and Channel 9’s commentators. Raygun, whose popularity and circulation can entirely be traced to live software technologies, is a software image who reproduces software, and, following theorists such as Wendy Chun and Adrian Mackenzie, resembles less the ‘real person’ for the purposes of our analysis, and more a particularly busy street in the ‘neighbourhood of relations’ that is software, where ‘relations are assembled, dismantled, bundled and dispersed within and across contexts’ (Mackenzie 169 in Chun 3). Towards this, the commentary of ‘[w]e are all Raygun’ is quite apt (FitzSimons). We—as global observers and commentators—all consume Raygun and (re)produce Raygun; we are the mediators, gatekeepers and meaning-makers, active participants in a continuous content churn. Raygun’s routine and the responses to it operate in a feedback loop where neither make sense, nor are any longer be accessible, in isolation.

While this focus on subject and responses as commonly and reciprocally implicated may be in keeping with some aspects of Ngai’s analysis, this is another area in which the zany is left wanting. The scale and chaos of this ‘Raygun mass’, made possible with high-speed internet and massive amounts of data, the capacity for instant content creation supported by rapidly advancing and adapting algorithms, and a politically fractured online audience primed for hot takes and wild (perhaps zany in themselves) conspiracy theories materially outpaces Ngai’s description and problematises some of her underscoring claims. Where Ngai’s zany is predicated on the rapidly shrinking distinction between work and play (Our Aesthetic Categories 231), with the Raygun phenomenon—which enfolds global competition and an academic career, as well as content generation for a continued stream of likes, subscriptions, and ad revenue—the distinction between work and play seems wholly irrelevant, even arbitrary or beside the point, and suggests a modified productive site in late capitalist processes which penetrates evermore into day-to-day life. To respond to these contemporary examples, the zany needs to become more inclusive of different, increasingly chaotic, affects, as well account for an adjusted playing field for aesthetic production and reception.

Understanding Ngai’s Claims

Ngai presents three aesthetic categories based on late capitalism’s ‘most socially binding processes’ of production, circulation, and consumption (Our Aesthetic Categories 1). Zany is about production and involves a ‘distinctive mix of displeasure and pleasure’ from the extreme lengths an actor goes to in performing a (productive) job (Our Aesthetic Categories 11). Interesting facilitates an information economy—when one says something is ‘interesting’, it is an invitation for further discussion mobilising ‘a desire to know reality by comparing one thing with another, or by lining up what one realizes one doesn’t know against what one knows already’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 6). Lastly, cute speaks to ‘a desire in us not just to lovingly molest but also to aggressively protect’ objects we have deemed as familiar and unthreatening, a desire which activates a deep sentimentality inhering in consumable commodities (Our Aesthetic Categories 4). Ngai claims that these categories have immense illuminative power amongst the chaos of postmodern life and culture, and function like ‘quilting points’ in ‘what might otherwise be a truly inchoate sea of postmodern styles and judgments’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 22).

To achieve the radical applicability which she describes, Ngai claims her categories are exclusive, and part of everyday experience. Regarding exclusivity, she states that ‘No other aesthetic categories in our current repertoire speak to these everyday practices of production, circulation, and consumption in the same direct way [as zany, cute, interesting]’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 1). This is to say, other categories in our ‘current repertoire’ such as camp, beautiful, sublime, and disgusting are unable to as effectively explain our conditions under late capitalism (Our Aesthetic Categories 12, 18). As David Gordon summarises: ‘We need not abandon the beautiful and the sublime, but we need to give attention as well to what best enables us to understand today’s culture, thus lessening the gap between aesthetic theory and practice’ (103). What makes Ngai’s aesthetic categories distinct is their ‘undeniably trivial’ status which binds them to the everyday (Our Aesthetic Categories 18). Ngai claims that zany, cute, and interesting:

[A]re not […] exotic philosophical abstractions but rather part of the texture of everyday social life, central at once to our vocabulary for sharing and confirming our aesthetic experience with others (where interesting is rhetorically pervasive) and to postmodern material culture (where cuteness and zaniness surround us). (Our Aesthetic Categories 29)

The revolutionary aspect of these aesthetic categories is that they are supremely quotidian—because they are so suffused into our day-to-day experiences as late capitalist subjects, they can shed light on our cultural touchpoints and modes of structuring. Zany, cute, and interesting need not be activated by some ‘moral and theological’ gravitas before becoming realised; they are constantly and atmospherically available to us and reflecting back on us as everyday words and judgments (Our Aesthetic Categories 18).

The width of Ngai’s claim has been criticised, however, for example in Douglas Dowland’s review where he writes: ‘Ngai’s range is encyclopedic: while such range is insightful, the book often feels unrestrained as Ngai attempts to negotiate the entire history of modern and postmodern aesthetic theory while simultaneously performing contemporary cultural criticism’ (97). Similarly, I suggest Raygun pressures Ngai’s claim for radical applicability because it reveals the zany’s slippage away from exclusivity and everyday prominence, and thereby lifts the unwieldy corners of her argument to which Dowland refers. Where Ngai’s claim reaches furthest, it is at its weakest. In a simple example, Raygun has been described using many words, but ‘zany’ is scarce among them, least of all in Australia where I am writing from. Other aesthetic categories not accounted for by the zany, or an assemblage of other aesthetic categories, may be better suited to aesthetically capturing Raygun and the cultural conditions shaping the phenomenon.

Zany is the most appropriate category here, as while Raygun includes elements of the cute and interesting, aesthetic responses generally didn’t see her as belonging to ‘the diminutive, the weak, and the subordinate’ and were not underscored by ‘the desire for an ever more intimate, ever more sensuous relation’ to her as an unthreatening object as in the cute (although some, including those featured above, did refashion her as a cute figure) (Our Aesthetic Categories 53, 3). Nor was this a case of the ‘interesting’ ‘filling the slot for a judgment conspicuously withheld’, with most responses being only too ready to mete out judgment, to present a definitive explanation, to already convince viewers and perspective critics exactly how to receive Raygun—too much immediate information and noise instead of a deferral for future pedagogy and processing (Our Aesthetic Categories 134, 171).

Another aspect of Ngai’s overall work worth flagging is the gimmick, which describes ‘overrated devices […] [that] strike us as working too little […] but also working too hard’ (Theory of the Gimmick 1). Raygun critics suggested that she had made the team through corrupt processes or had ‘sucked on purpose’, likely for political or academic purposes (Beazley). For them, the best way to ‘explain’ Raygun was that she was either not trying hard enough (and needed a fraudulent hand up) or trying too hard (to play some covert double game). In comparing gimmick and zany, Ngai notes the ‘gimmick however uniquely reflects on the interlinking variables that makes capitalist exploitation measurable, even if, as an aesthetic rather than cognitive judgment, it leaves its own estimations blank’ (Theory of the Gimmick 38). As our inquiry is less concerned with ‘devices’ and the variables that make capitalist exploitation measurable, zany remains our principle point of reference.

The zany is characterised by its ‘stressed-out, even desperate quality’ which sees ‘action pushed to strenuous and even precarious extremes’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 185). Ngai describes zaniness as:

[T]he only aesthetic category in our contemporary repertoire explicitly about [the] politically ambiguous intersection between cultural and occupational performance, acting and service, playing, and laboring. Intensely affective and physical, it is an aesthetic of action in the presence of an audience that bridges popular and avant-garde practice across a wide range of media. (Our Aesthetic Categories 182)

The zany is activated when we witness incessant activity—a confused, wayward need to produce, to maximise output at any given time in a ‘perpetual improvisation and adaptation to projects’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 189). Indeed, the zany subject has been so overwhelmed with projects, such that their own lives (like their constantly updating list of ‘to-dos’) become ‘dissolved into a [sic.] undifferentiated stream of activity’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 231). Ngai traces the zany etymologically and historically to the zanni/zagna, in which ‘personal services [are] provided in the household on a temporary basis’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 194). Similarly, in her post-Fordist examples such as The Cable Guy (a movie some commentators have directly compared Raygun to!) the zany occurs where productive projects intrude into a domestic environment, leading to frantic ‘scenes of unfun fun’ (OzzyManReviews; Our Aesthetic Categories 198). These are superficially ‘fun’ activities whose playful, innocent veneers are uncannily underscored by an imperative of production and the fragmented agent charged with doing multiple things at once, and as quickly as possible.

Breaking Zany

The process of breaking seems a perfect site for the zany’s ‘aesthetic of incessant doing, or of perpetual improvisation and adaptation to projects’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 189). In breaking, dancers ‘battle’ one another while surrounded by a group of interactive onlookers (the ‘cypher’), while responding to a DJ’s improvisations and their opponent/s’ moves:

In the battle scenes, dancers stand facing one another and perform their improvisational dance for 30-40 seconds in turns. Dancers in break dance have to perform while listening to unfamiliar music, communicating with an opponent, and responding to the dance of the opponent. Hence, the battle scenes of breakdance are highly improvisational. (Daichi and Takeshi 2322)

Breakers, then, are faced with a rapid succession of multiple projects or shifting interactive points—the music, the cypher, the opponent—which force them to adapt and/or respond. A missed cue or an awkward deployment of one of breaking’s key patterns is a lost opportunity which could potentially prove catastrophic for the competitor’s standing and competitive claims. While breaking is not always zany, we can observe that the precarious elements are there for the ‘hot under the collar’ zany figure to rapidly emerge (Our Aesthetic Categories 7)—a slip up, a break in flow, an intimidating gesture getting to a dancer’s head as they find themselves one step behind the overwhelming demands of music, cypher, opponent, ad infinitum (or at least until the dance is over). The naming of the competitive circle as ‘cypher’ is particularly interesting here—like a codebreaker tasked with making sense of ‘a message in code’ (‘Cipher’), the breaker must always stay on top, lest they fall behind and reveal themselves comically out of the loop, their moves dissolving into an ‘action pushed to strenuous and even precarious extremes’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 185). The constant threat of non-understanding precariously summons the spectre of the zany.

In her own academic writing, (Ray)Gunn describes her first experience witnessing a b-girl perform at the Australian B-Boy Championships. This included a mixture of nervousness, excitement, and vicarious experience, culminating in a moment of inspiration and determination:

I was struck by her confidence to step into the centre of a circle of dancers (a cypher) and perform a series of fast, intricate combinations of kicks, spins, jumps, and slides, and then nonchalantly return to the circle’s edge. […] It was in this moment that I decided to commit to learning breaking. (1447)

This touches on—while not just yet fully activating—the key tenets of the zany described so far, chiefly the combination of the intensely homely and familiar (the vicarious experience and sense of freedom, dance as a form of liberating self-expression, and possibly the aesthetic of the ‘street’ environment (Campos, Pavoni, and Zaimakis (eds)), with the imperative to transform it into work (the determination to learn the form, and make something of it to the point of being competitive). Gunn’s observance of the breaker’s confidence neatly follows Ngai’s analysis, where in the zany spectacle ‘the experience of zaniness ultimately remains unsettling, since it dramatizes, through the sheer out-of-controlness of the worker/character’s performance, the easiness with which these positions of safety and precariousness can be reversed’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 11). In recognising the breaker’s confidence, Gunn refers to the precariousness of their position and the inherent risk tied to the intense and intricate spectacle of ‘kicks, spins, jumps, and slides’. Her anecdote finishes with tacit acknowledgement of her own need to build up this same confidence as she transforms from spectator to participant, substituting her position of safety for one of precariousness. The sensation is a thrilling and motivating one, yet it carries with it the unsettling counterpart of possibly not being able to achieve the right level of confidence, or suddenly reverting back to the same state of stunned, confused awe characteristic of the fascinated yet uninitiated—the paranoia of becoming zany, against the thrill of narrowly avoiding such.

Figure 2. A still of Raygun’s upside-down face (AFP Wire Services)

Figure 2. A still of Raygun’s upside-down face (AFP Wire Services)

Amongst Raygun media, commonly proliferated photos and videos seem to bear a common fascination with her face, with a focus on facial expressions that present her as flustered, confused, haughtily arrogant (which arguably would be in keeping with the ‘battle’ nature of the sport), or sometimes eminently loveable. In contrast to many of the other memes coming out of Paris 2024 which emphasised particular moments and facial expressions (for example those of Turkish marksman Yusuf Dikeç (Knowyourmeme)), Raygun was especially multiplicitous—she was many things, but certainly not restrained and at best barely composed. In the now-iconic image above for example, the profile of Gunn’s face gives the impression that she is struggling to pull off her headstand—it almost seems like she is drowning [Figure 2]. Her face is distorted, and the sharpness seems to draw attention to her makeup as façade. The extremely shallow focus turns her head into a comically large spectacle, as if we are seeing something in the vein of James and the Giant Peach. We seem to have literally zoomed in on a private moment, where things are about to fall apart—perhaps already have fallen apart. In his guidance for sports photographers, Peter Read Miller notes the difficulty with filming gymnasts: ‘their faces are often distorted into masks of fear, stress, pain, or just plain weirdness. Add to this the fact that no one looks good upside down […] Faces wrinkle in odd ways, hair flies wildly, and eyes bulge’ (unpaginated). Yet these qualities seem to be exactly what have made this image and so many others so compelling and shareable—the usual rules for what makes a sport photograph ‘good’ have literally been turned on their head; in a contest between personality and prowess, the personality has become the prowess. For Raygun critics, these facial expressions seemed to be a shifting, readily adapting, source of backpfeifengesicht, while for supporters her face cemented her place as an unhinged icon truly existing in her moment (McGuire).

Similarly, the zany is marked by its chimeric, multi-role, multi-faced, quality: ‘Far from being “divinely untroubled,” zaniness projects the “personality pattern” of the subject wanting too much and trying too hard: the unhappily striving wannabe, poser, or arriviste’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 188). As a zany figure, Raygun cannot settle on one face or one subject position. Continuously and frantically involved in pattern to pattern, project to project, move to move, meme to meme, yet nary seen with a straight, laconic face—or at least an expression composed enough to refute an onslaught of accusations and conspiracy theories—Raygun embodies how with the zany, the ‘desperation and frenzy of its besieged performers, due to the precarious situations into which they are constantly thrust, point to a laborious involvement from which ironic detachment is not an option’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 12). If the zany is about the plasticisation of the human body in response to capitalistic demands, then the contorted images of Raygun’s face act as synecdoche for the ways in which she has been plasticised by rapid media processes.

Breaking Beyond Zany

What other affects are at play when we comprehend Raygun? One of the key terms associated with Raygun is ‘cringe’, with some punters (falsely) claiming that her routine was so cringe-worthy that she single-handedly prevented breaking from appearing in future Olympics competitions (Cheong; Pu). ‘Cringe’ has drawn cultural and critical attention since the early 2000s and has been described as ‘a form of hostility against others and the form of life they exhibit, albeit non-violent hostility which is in line with the proliferation of pluralistic forms of life’ (Spiegel 2). Countering these are the responses which have stuck up for Raygun, such as the #istandwithraygun trend on X (formerly Twitter). These commentators have labelled Raygun critics ‘un-Australian’ and choose to instead draw attention to Gunn’s ‘creative and individual’ achievements as an Olympian and cultural theorist (THE Russell; Hastings). Far from seeing Raygun as a zany spectacle or cringe social outcast, these responses have instead conceived of her as a loveable and admirable icon. Another aesthetic response was larrikinism—a culturally specific affect evident in statements from Australian officials such as Chef de Mission Anna Meares and Prime Minister Albanese who applauded her for demonstrating ‘the Australian tradition of people having a go’ and implicitly laid a genealogic link between Raygun and the ‘innocent victimhood of the convict’ (AAP; Albanese in Convery and Cox; Blaine 13). On the sustaining of the larrikin’s principles in the contemporary era, Lech Blaine writes: ‘The larrikin is dead. Long live the larrikin! Anti-authoritarianism doesn’t need the vocabulary of the bush poets, the accent of Mick Dundee […] It sounds like Grace Tame, and acts like Behrouz Boochani, and looks like Adam Goodes’ (101). Perhaps it dances like Raygun too.

We need to take seriously Ngai’s claims that her three aesthetic categories draw their explanatory power from being exclusive and everyday. I do not contend that cringe, loveable, and larrikin are new aesthetic categories of tantamount weight and power to Ngai’s, but they do all describe affects and aesthetic contributions which appear to fall outside zany’s remit. These aesthetic categories arguably displace fundamental pillars of her argument as they were far more commonly used in the texture of everyday social life regarding Raygun. Use the search term ‘Raygun zany’ on X, and (as of writing) less than half of the results are about the breaker. In comparison to these terms, which largely speak for themselves, ‘zany’ seems like the ‘exotic philosophical abstraction’ which is best applied to the situation through the process of lengthy exegesis (see my analysis above) (Our Aesthetic Categories 29). In my analysis alone, using terms beyond ‘zany’ has allowed us to examine a richer canon of aesthetic responses and judgments that together form what we talk about when we talk about ‘Raygun’—including more positive and earnest responses compared to those which treat her as an object of zany spectacle and ridicule. Describing Raygun as ‘zany’ seems to do Raygun, and the genuine responses of sympathy, affection, and admiration for her, a fundamental disservice.

What happens to the zany’s explanatory power of late capitalist processes if we accept that it could have fallen out of fashion, and is no longer central to our vocabulary? To an extent, this ‘end’ of the zany was foregrounded in Ngai’s writing, where she observes:

‘Zany’ thus seems to be in the process of slowly vanishing from our lexicon of feeling-based evaluations, even as ‘cute’ and ‘interesting’ have come to dominate it. Ironically, this aesthetic category about high-affect performance is noticeably weak as a performative utterance, and particularly deficient in both verdictive and imperative force. […] The aesthetic category of the zany, as such, thus becomes profoundly ambiguous and unstable. (Our Aesthetic Categories 231)

Ngai goes further to explain this apparent weakness, claiming that ‘the shrinking distinction between work and play’ is correlated with ‘the shrinking of an aesthetic capacity caused by it’ and that it is ‘precisely in accord with how the object style of post-Fordist zaniness qua aesthetic of desperate laboring/performing continually points to the conditions of its own aesthetic ineffectuality’ (Our Aesthetic Categories 231, 235).[1]

But what if the friction point between work and play is no longer desperate or ineffectual, but for all intents and purposes quite immaterial—no longer a rich source of aesthetic power but a discarded plaything? Anna Kornbluh provides a different perspective on late capitalist productive processes in her writing on immediacy, where:

underlying all these compressions and expressivities is the economy of hurry and harry, same-day shipping and on-demand services, where the ease of one-click buying covers up a human hamster wheel, and innovative circulation pulls off a just-in time deflection from the multi-decade crisis in capitalist production […] ‘Immediacy’ names a unifying logic that should also aid us in interpreting separate instances; if we want to understand what is going on with mediation, what is up with immersive art or cringe TV or antifictionality, it helps to theorize their categorical commonalities (4-6).

In these new conditions of ‘too late capitalism’ whereby ‘we are fastened to appalling circumstances from which we cannot take distance, neither contemplative nor agential’, it is no longer the case that productive demands are zanily trying to do too many thing at once—now they are successfully doing too many things at once; may even have already done too many things at once (6-7). In Raygun’s case, stepping away from the zany allows us to perceive a legion of immediate, potent, and contradictory affects and processes and sites, simultaneously too much and not enough happening at once to generate contemporary capitalism’s latest infinitely exploitable resource of content (which enables ad revenue, subscriptions, shares, investments, platform upgrades, ad infinitum). I say too much and not enough, as simultaneously there is far too much media on Raygun for one (human) social agent to receive, yet at the same time there continues the imperative to keep generating more memes, more headlines, more shareable content.[2]

The eclipse of the zany, heralded by Ngai in her own writing, seems to have come about lexiconically as the conditions for the zany have themselves been eroded. If the zany originally came about due to an inefficiency within the capitalist system, then the end of the zany comes about through a smoothing out of that inefficiency; the employment of new algorithmic platforms capable of handling the pluralistic and contradictory productive demands of its users, the implementation of a new form of capital in content generation that is able to exist immediately, simultaneously, and chaotically. The aesthetic result of these new means of production is something exponentially more multivariate, simultaneously more demeaning and more sincere, than anything heretofore explained through the zany.

Conclusion

Where to now, if we are living through the death of the zany? Future research might propose new categories or update the definition of the zany to more suitably describe what we have covered here. When I consider Raygun, aesthetic categories such as ‘awesome’ or ‘iconic’ come to mind—perhaps my personal response is a resigned embrace, vacillating swiftly between ironic and unironic. Yet this too seems to fall short in the intensity and immensity of the Raygun obsession. As we consider new modes and categories, and even the continued usefulness of already accepted modes and categories, it is worth bearing in mind that capitalism’s principal aim is to expand, even and especially to the point of crisis (Marx 41). Attempts to categorise and bind up its productive and aesthetic outputs, then, will always be pressured by the next crisis, the next bubble, the next thing.

Jeremy Tsuei completed his English Honours research project in 2024 and was a recipient for the Grahame Johnston Prize in Australian literature for his thesis, ‘Theorising the Dingo Howl: Jazz in Australian Film in the 1990s and Early 2000s.’ His work has also been published in the ANU Undergraduate Research Journal and on the ANU College of Law’s website. Although Jeremy is not (yet) a breaker, he is also a keen jazz musician.

Notes

[1] One could also observe the ‘shrinking distinction between work and play’ in debate between the term ‘breaking’ as opposed to ‘breakdancing’, with the former seen by practitioners (including Gunn) as a more ‘authentic’ term against the institutionalised and sportified latter term. These terms seem to enfold to work/play tensions and ideas of ‘unfun fun’ in unstable ways. Breakers refer to ‘breaking’ the culture, while simultaneously the term ‘breakdancing’ seems to refer to the culture which is being broken—indeed a breaker might well claim that the ‘real work’ is in breaking, and not in breakdancing. The slippage between these two terms in common use and media environments, and the insistence on their opposite yet dyadic relationship, suggests that there is much work to be done in play yet. The distinctions between these work/play notions, as we will go on to discuss, are likely no longer evident at all, even as the terms ‘breaking’/ ‘breakdancing’ fluctuate in use, legitimacy, and license.

[2] The potential for AI to speak to this new sense of aesthetic desire or hunger is immense, given its potential to generate infinite variations of content (or ‘slop’) almost instantaneously. In one video, the creator had fed Raygun’s performance into Midjourney (or similar), and generated warped, surrealistic images of the breaker that saw her body folding in on itself and morphing into a headless torso with multiple flailing limbs. In a rush to generate seemingly new variations out of algorithmically catalogued information, we have a literal ‘falling apart’, a plasticisation, transfiguration, and mutilation of the human body through the digital medium of the (potentially) viral meme.

Works Cited

AAP. ‘“It took great courage”: Australia’s Olympic chief defends “Raygun” against online abuse.’ SBS News 11 August 2024. <https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/i-love-her-australias-olympic-chief-anna-meares-defends-breaker-raygun-against-wave-of-online-abuse/uuutd9lwl>.

AFP Wire Services. ‘Australia’s Raygun officially ranked as the world’s best female breakdancer.’ IOL 11 September 2024. <https://www.iol.co.za/sport/olympics/australias-raygun-officially-ranked-as-the-worlds-best-female-breakdancer-5a5bde30-3e4f-4f32-bb55-80b92bdce6d9>.

Beazley, Jonathan. ‘Raygun: Australian Olympic Committee Condemns “Disgraceful” Online Petition Attacking Rachael Gunn.’ The Guardian 15 August 2024. <https://www.theguardian.com/sport/article/2024/aug/15/raygun-olympics-breaking-petition-aoc-response-ntwnfb>.

Beetoota Advocate. ‘RAYGUN Limited Edition Black T-Shirt.’ Beetoota Advocate. <https://shop.betootaadvocate.com/products/raygun>.

Blaine, Lech. 2021. ‘Top Blokes: The Larrikin Myth, Class and Power.’ Quarterly Essay 83 (2021).

The Cable Guy. Dir. Ben Stiller. Perf. Jim Carrey, Matthew Broderick and Leslie Mann. 1996.

Campos, Ricardo, Andrea Pavoni and Yiannis Zaimakis, eds. Political Graffiti in Critical Times: The Aesthetics of Street Politics. New York: Berghahn, 2021.

Channel 9. 9Now. August 2024. <https://www.9now.com.au/>.

Cheong, Ian Miles [@stillgray]. X. 13 August 2024. <https://x.com/stillgray/status/1823078830250315811>.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Programmed Visions: Software and Memory. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011.

‘Cipher.’ Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cipher>.

Convery, Stephanie and Lisa Cox. ‘Albanese praises breaker Raygun for having “a crack” – as it happened.’ The Guardian 11 August 2024. 3 September 2024. <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/live/2024/aug/11/australia-news-live-anthony-albanese-murray-watt-mike-burgess-asio-queensland-stabbing-cost-of-living>.

Cowland, Andy. ‘Twin Peaks Logposting – Raygun.’ Facebook. 20 August 2024. <https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=10219848490681092&set=gm.3383473191961664&idorvanity=1528224180819917>.

Daichi, Shimizu and Shultz Takeshi. ‘Creative Process of Improvised Street Dance.’ Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (2012): 2321-2326.

Dowland, Douglas. Review of Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting, by Sianne Ngai. American Studies 53.3 (2014): 96-7. <https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/ams.2014.0142>.

Doyle, Michael. ‘Rachael “Raygun” Gunn Says Criticism Over Paris Olympics Performance is “Pretty Devastating.”’ ABC News. 15 August 2024. <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-08-15/raygun-calls-for-end-to-pretty-devastating-criticism-olympics/104232074>.

FitzSimons, Peter. ‘I am Raygun. You are Raygun. We are all Raygun!’ Sydney Morning Herald 11 August 2024. <https://www.smh.com.au/sport/i-am-raygun-you-are-raygun-we-are-all-raygun-20240811-p5k1f5.html>.

Gordon, David. Review of Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting, by Sianne Ngai. Library Journal (2012): 103.

Gunn, Rachael. ‘Where the #bgirls at? Politics of (In)visibility in Breaking Culture.’ Feminist Media Studies 22.6 (2022): 1447-62. <https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1890182>.

Hastings, Fred [@HastingsFred]. X. 11 August 2024. <https://x.com/HastingsFred/status/1822595296356147299>.

James and the Giant Peach. Dir. Henry Selick. Perf. Paul Terry, Simon Callow and Richard Dreyfuss. 1996.

Jensen, Jayson [@JaysonJensen5]. X. 8 September 2024. <https://x.com/JaysonJensen5/status/1832602502447137194>.

Knowyourmeme. ‘Yusuf Dikeç Turkish Pistol Shooter.’ Know Your Meme. August 2024. <https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/people/yusuf-dikec-turkish-pistol-shooter>.

Kornbluh, Anna. Immediacy, or The Style of Too Late Capitalism. Verso Books, 2024.

Mackenzie, Adrian. Cutting Code: Software and Sociality. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2006.

Marx, Karl. Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Penguin, 1939-41.

McGuire, Jess [@jessmcguire]. X. 10 August 2024. <https://x.com/

search?q=raygun%20unhinged&src=typed_query>.

Miller, Peter Read. ‘The Olympics Big Three: Swimming, Gymnastics, and Track and Field.’ Peter Read Miller on Sports Photography: A Sports Illustrated Photographer’s Tips, Tricks, and Tales on Shooting Football, the Olympics, and Portraits of Athletes. New Riders, 2013.

Ngai, Sianne. Our Aesthetic Categories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2012.

—. Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 2020.

OzzyManReviews. ‘Ozzy Man Reviews: Raygun.’ Facebook. 13 August 2024. <https://www.facebook.com/watch/?ref=search&v=816377193819810&external_log_id=f89fac83-7804-4220-905e-62124adb2380&q=i%20stand%20with%20raygun>.

‘Breaking.’ Olympics.com. Paris 2024. <https://olympics.com/en/paris-2024/sports/breaking>.

Pu, Jason. ‘Breaking Will Not Be In the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics—What’s Next?’ Forbes 15 August 2024. <https://www.forbes.com/sites/jasonpu/2024/08/15/breaking-will-not-be-in-the-2028-los-angeles-olympics-whats-next/>.

SBS News. ‘Rachael “Raygun” Gunn.’ Facebook. 10 August 2024. <https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=917834200388141&set=a.617456000425964>.

SèánoSerious [@MovedOnNotice]. X. 11 August 2024. <https://x.com/MovedOnNotice/status/1822477749900222810>.

Spiegel, Thomas J. ‘Cringe.’ Social Epistemology 1.1 (2023): 1-12.

Stewart, Ky. ‘The Olympics of Culture Wars.’ Junkee. 13 August 2024. <https://junkee.com/articles/2024-olympics-culture-wars>.

THE Russell [@THE_Russell]. X. 11 August 2024. <https://x.com/THE_Russell/status/1822408084720935173>.

Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, The. ‘Rachel Dratch Interrupt’s Jimmy’s Monologue as Australian Olympic Breakdancer Raygun.’ YouTube. 12 August 2024. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8q1d4LZb1Y>.

Tocci, Nathalie. ‘A Global Conflict Is Playing Out At the Paris Olympics—Just Not in the Way We Think.’ The Guardian 8 August 2024. <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/aug/08/paris-olympics-culture-wars-russia-west>.

Turnbull, Tiffanie and Isabelle Rodd. ‘How Raygun Made It to the Olympics and Divided Breaking World.’ BBC. 18 August 2024. <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4gl34v4r98o>.

WatchMojo. ‘Top 10 Illest Raygun Moves.’ YouTube. 14 August 2024. <https://www.youtube.com/shorts/bi2x9f_DcZM>.

Wood, Leslie. ‘Twilight Shitposting.’ Facebook. 11 August 2024. <https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=26237978455847066&set=gm.2877056429138290&idorvanity=1685087155001896>.