By Brian Opie

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version. doi: 10.56449/14698743

The term humanities has little or no influence on decision-making by governments and the major institutions which provide form and continuity to democratic societies and individual lives. But there is no better term in English for the kinds of knowledge to which it traditionally refers. The university as an institution exists to locate a society’s advanced knowledge capabilities within the global spectrum of knowledges. It therefore differs in two important ways from other organisations—such as research institutes—working with knowledge at the most advanced levels. Firstly, it perpetuates a commitment to make access to the whole of human knowledge locally available; and, secondly, it is required not only to advance knowledge but to educate new generations in its understanding and social uses.

More than any other social institution, the university must not only react to changes in its environment, but it should be anticipating those changes by creating the knowledge needed to understand and shape them to good ends. While this new knowledge may be of global significance, I would argue that a particular society or nation invests in a university so that its citizens can achieve more of their goals for the future of their society through being well-informed about the challenges facing them and the possible ways of arriving at socially inclusive, productive solutions. These are social and human requirements beyond the ambit of science and even the social sciences.

At present, however, as a consequence of the universalist model of scientific research and the neo-imperialism of global corporations, universities are typically expected (and now put this expectation upon themselves) to be engaged in research according to programmes and criteria established by the most scientifically advanced nations, those nations where the ‘international’ standards for evaluating and rewarding research are set.

I am not trying to argue that knowledge creation is carried out in hermetically sealed domains, but that fundamental differences in object and method constitute two complementary and overlapping worlds of mind. The science system is distinguished by:

* its ‘given world’ objects of research;

* the search for universals, by experimental methods and quantification;

* its progressive conception of the discovery and obsolescence of knowledge, and the power of that knowledge when applied to materially transforming the given and social worlds;

* the commercial contexts in which its knowledge is valued;

* and its imperial tendency to assume or require communication in one dominant language.

There is no aspect of this list to which the humanities can properly conform, however much current policies for research evaluation and funding have required the academic humanities to accept technologies of measurement and evaluation based on the science system. The assumption that the research methods, practices and institutional formations specific to technoscience are universal dislocates the work of humanities research; the historically evolved, learned and internalised structuring of the former mode fails to mesh with the historically evolved, learned and internalised structuring of the latter.

Nevertheless, as John Hartley observes, ‘the distinction between the humanities and the sciences is itself dynamic’ (36). What needs to be recognised and properly theorised in policy work on knowledge systems is (1) the multiplicity of knowledge cultures within the frames of the two modes, and (2) the fact that the effective social, cultural and economic adaptation of any society to its existential conditions depends on the quality and openness of the interactions between these modes.

A compelling analysis of what is at stake is offered by Ronald Barnett in The University in an Age of Supercomplexity: ‘The new university that is not doomed to repeat the past (viz., the modern university) and not committed to making the mistakes of the present (viz., the neoliberal university), might be called, for lack of a better term, the “postmodern” university’ (22). The basis for this renaming is four concepts which Barnett takes to characterise postmodern societies and therefore the conditions under which individual subjectivity is formed, institutions now operate, and knowledge work is carried out: uncertainty, unpredictability, challengeability, and contestability (68). Supercomplexity is the combined effect of these qualities, in all domains of life, exemplified by what he calls the ‘discursive maze’ of postmodern knowledge: ‘The global age spawns continuous reframing in culture, work and life more generally. It is this continuous reframing that produces supercomplexity in which all our frames of understanding are challengeable’ (144).

For Barnett, the postmodern university will become a ‘pivotal institution precisely through its insight into the character of this world and through the human capacities it will sponsor to confront that world … creativity accompanied by critique’ (69). The tasks of intellectual work in the humanities are therefore to reveal to a human collective what has not yet become apparent in their thought about themselves, and also to illuminate previously unexplored dimensions of the idea of humanity. To pursue these tasks fully is to bring all knowledge, in all times and places, within the scope of humanities enquiry and to centre that enquiry on the question, what (more) does it mean to be human (than humanity already understands)? It grants a fundamental value to thought itself as a way to arrive at valid knowledge and truths.

To this end, the first of the following sections draws out the implications of the foregoing for the educative functions and institutions of the state, focusing in particular on a reconfigured university as a key institution into the future, and as a model by which to explore the roles of future humanities practitioners. The subsequent section completes and reinforces the argument by providing an elaboration of poetic thinking that would characterise what could be called ‘the poetic university’. Such a university, which would seek to place creativity and innovation in thinking at its foundations, must not only admit a claim to new knowledge from the humanities equal to that of the sciences; it must grant that singular thought, founded axiomatically, theorised and informed by immersion in some aspect of humanity’s collective knowledge, can generate new possible truths.

Settings and Institutions of Cultural Policy for an Education State

A knowledge society objectifies ordinary cognitive and communicative capabilities in the formation of specialised institutions for creating various types of knowledge. As Søren Brier puts it, ‘All these types of knowledge have their origin in our primary semiotic intersubjective life world of observing’ (‘Cybersemiotics: Merging’ 16). On this ground he argues both that ‘It is the human perceptive and cognitive ability to gain knowledge and communicate this in dialogue with others in a common language that is the foundation of science’ (Cybersemiotics: Why 83), and that, as a consequence, ‘the methodological ideals of science, as well as the actual practice of science, are cultural products made by human minds linked by meaningful language communication in a society with a cultural horizon of meaning’ (‘Cybersemiotics: An Evolutionary’ 1904).

Observation, and the technologies to record what is observed and to render it observable when unaided human senses are insufficient to perceive what is there to be observed (electron microscopes, the Hubble telescope, cameras, radar and so on), are fundamental to the growth of knowledge about ourselves and the world of which humanity is a part; but, as Brier observes, observation itself is a culturally framed activity, as are the institutions set up to regulate the creation of formal knowledge from it.

The work of the institutions of the state which command the high ground of policy is informed by knowledge derived by observation and perception of reality, natural and social, by members of those institutions, but, even more, by others outside their borders, who define the standards against which the truth value of such knowledge is assessed. An important effect of this orientation is to sustain the conviction that the work of Western governments is grounded in reality, even though much of that work is about hypothetical states of affairs, contingencies, and potentials in that segment of reality which is the relations within and between states as the present moment transitions to its future form.

Even if the administrative functions of the state continue to implement and enforce procedures which were developed in the past and have become (for good or ill) normalised as part of regulated social reality, its policy functions—confronted by hypotheses, contingencies, conflicting imperatives and imminent but indefinite futures—can only achieve a similar stability by imposing continuities on what is fundamentally discontinuous and heteronomous. If the condition of policy is also the condition of a culture when it is open to rather than reactive against or closed from its situation in the world of cultures and their impending futures, then cultural policy (with the arts as primary sources of observation and perception) becomes a powerful alternative basis for policy formation across the institutions of government.

In effect, all public institutions include within their scope observing ourselves and the given world from a specific position in it. Their potential power and public value lie in the ways that they can extend a singular mind’s perceptual processes for gaining information and producing knowledge by thought from it. Their unique responsibility, to observe what happens in all the dimensions of a nation’s life, discovering patterns, and providing information to government and the public—factually or fictionally, scientifically or artistically, in print or digitally—is central to the competence of a postmodern state.

The concept of an education state has been advanced by Mark Olssen, John A. Codd and Anne-Marie O’Neill in a wide-ranging study which was intended to critique the dominance of neoliberal economic theory in public policy and legislation and to reaffirm the fundamental importance of universal public education in the sustaining of a democratic society in a globalising world order. The study adopts:

a democratic model which, while it would seek to preserve and protect the important principles of liberal constitutionalism, locates these within a communitarian context, where they are allied to a concept of social inclusion and trust. Only such a model … can support a conception of education as a public good. In its turn, education … is seen as pivotal to the construction of a democratic society, and for the model of citizenship that such a conception implies. (15)

An education state is one committed to ensuring that its citizens have access to the knowledge they need to live well as citizens; knowledge which can only be acquired progressively as children become adults and assume adult responsibilities and roles. Such knowledge is finally an account for that time and in that society of what it means to be human; it cannot be provided or acquired only through a formally constituted curriculum (although some agreement on knowledge that all must have is needed in the public or formal education system), because all kinds of experiences and relationships contribute to each person’s understanding of themselves and their world. But the state must take responsibility for ensuring that there is open access to knowledge about all aspects of the functioning of society, including its history (cultural, social, political, economic), its laws, its institutions, its media, how it is governed, its military and police functions, how its wealth is managed and distributed, how it changes over time, and the role of citizens in this process of adaptation and innovation. Its citizens are the fundamental resource of a democratic state, not to be exploited for profit but, through understanding, to contribute in singular and collaborative ways to advancing the interests of society as a whole.

In the space available, one key and exemplary setting (fiction) and one key and exemplary institution (the university) for the construction of an education state worthy of the description just given are discussed below.

(a) Fiction at the Core of Policy

Placing art within the scope of institutions which conceive of their work as based solely on observation and perception of the real world makes possible a significant disruption of current conventions. Luhmann builds a fundamental part of his analysis of the art system on the position that

The work of art … establishes a reality of its own that differs from ordinary reality. And yet, despite the work’s perceptibility, despite its undeniable reality, it simultaneously constitutes another reality, the meaning of which is imaginary or fictional …. The function of art concerns the meaning of this split.

‘The imaginary world of art’, he elaborates,

offers a position from which something else can be determined as reality—as do the world of language, with its potential for misuse, or the world of religion, albeit in different ways. Without such markings, the world would simply be the way it is. Only when a reality ‘out there’ is distinguished from fictional reality can one observe one side from the perspective of the other. Language and religion both accomplish such a doubling, which allows us to identify the given world as real. (142)

This double perspective is intrinsic to human thought; it is a very special kind of cultural and knowledge politics that would highly value knowledge derived from empirical reality and deny equivalent value to knowledge derived from fictional reality.

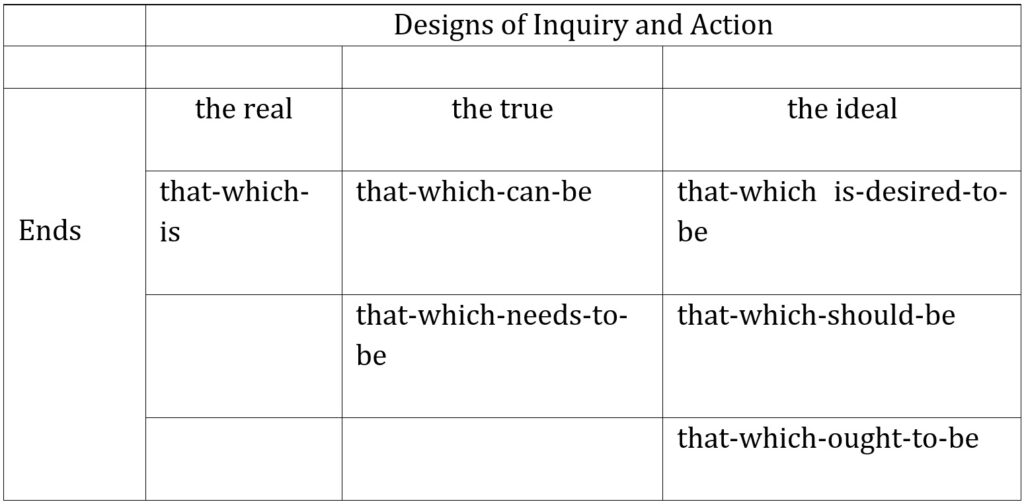

A table compiled by Harold G. Nelson and Erik Stolterman (second edition 39) to represent how the outcomes of a design process are dependent on the forms of enquiry being adopted is very helpful in this context for identifying the diversity of positions for thought which language makes available, and which collocate with fictionality:

As Nelson and Stolterman observe, while change is a condition of life in the given world, designed change is a function of human intentionality, and consequently ‘the kinds of outcome available to a change process vary wildly’ (first edition 43). Put another way, five of the six ends referenced in the table represent aspects of potentiality and emergence which are first realised in thought, imagined and objectified as texts (meeting reports, design briefs, plans, blueprints), before becoming new real things in the world.

Mapping this table together with Brier’s and Luhmann’s conceptions of the integral role of fiction in human thinking produces a critical conclusion: the scope of the domain of fiction in mental work, which is also the space of the imagination, is massively greater than the scope of the real. And it is not possible to have the one without the other. For Luhmann, fiction is that operation which inserts thought into the world as texts constructing and communicating manifold imaginable, and therefore possible, conceivable and enactable, forms of reality.

By contrast, those texts, and notably official texts, which claim to be governed by the real, are in fact governed by current conceptions of reality. In that respect, they largely diminish the possibility of significant innovation (in contrast to small variations on what is already the case) when written in conformity to current conceptions rather than by reaching forward into what is yet to be known. Policy work and those who commission it need to recognise the integral role played in it by fiction, and to give high value to culturally inflected knowledge and to those equipped to apply it. This would permit, for example, a movement away from the attempt to bring traditional knowledge within the limits of Western science by using a descriptor like ‘indigenous science’. Instead, attending to the distinctive ways in which the diverse modes of acculturated human perception have observed reality and conceptualised it can open possibilities for thinking that have become blocked by a particular acculturated conception of reality.

Humanity lives among possible worlds as well as on this planetary one. Critical to our species’ capability for survival in and modification of our given world is the objectification of possible worlds in ways which allow collectivities of minds to think, plan and act together in the implementation of originally singular new thinking. Exemplary forms of this process of textual objectification are the texts which provide the principal objects of enquiry in the fields of literature, media, and creative and performing arts: narrative fictions. Furthermore, as Hastrup argues in respect of theatre, narrative fiction can generate culturally transformative meanings from an asymmetrical relationship between the knowledge and experience of its readers/spectators and its representation of knowledge and experience in the world imaginatively realised from performing a theatre text. This capability of fiction, and the work of interpretation carried on in the humanities, are together crucial in giving effect to their joint role in the creation of new knowledge in culture.

What would be the role attributed to fiction in a university, or the Treasury or the Parliament, of an education state? Would it be marginal, as at present, valued as creative writing and so adding the traditional lustre of the arts to the truth-creating work of the sciences, or would it become a core source of the energy and vitality of the knowledge work of a creative university or an innovative government—the work of fiction holding equal place with the work of science in new knowledge creation?

No government is wise enough to see into the future, except in the form of best guesses made on the basis of forward projections from the present; but these are usually defined by organisations with interests in the outcome. What if speculative or future fiction became a basic source of cultural policy? The imperial expansion of the culture and methodologies of science has served to suspend or marginalise modes of thinking about complexity which have their basis in the human capacity to conceptualise complexity and to perceive it in social and cultural, rather than natural, terms.

Literary fictional forms are the exemplars of this situation. Currently, they are of no account in official thinking about knowledge, which is dominated by modernist scientific models. But they are the exemplars, because the matter from which they are composed is language, spoken and written—that is, symbolic matter—and the forms in which they are composed are means by which the uncontrollability/heterogeneity of language, society, subjectivity, human time and space is brought momentarily into an order which is conceptual, psychodynamic, perceptual, cognitive, social, cultural.

That which distinguishes the human in nature—that is, societies and cultures linguistically articulated, in values, ideologies, beliefs, politics, fictions, difference of all kinds—are elements in the production of knowledge with a much longer history than science. This knowledge is governed by other rules than those which govern science: most particularly, textual interpretation—not research in the scientific sense of the term—is the method by which new knowledge is produced; and fictional texts cannot be contained within any fixed system or grid of truth but always exceed any such system, and are always productive of different interpretations as the context of their interpretation changes.

A compelling example, given the present trials and failures of democratic societies, is Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, with its anticipation of faceless control through self-surveillance by democratic election, warfare engaged in by invisible elites, and the role of mass media in achieving and maintaining this state of affairs through the control of information in education and entertainment. But democratic governments are charged with responsibility for guiding the evolution of society towards a better version of itself, its fictional or possible futures implied, but not described, in the democratic principles informing public thought and values. It is the possible worlds imaginable from these principles which an education state would employ its resources to articulate in all their diversity in order to extend the boundaries of public knowledge, public thinking, public policy and decision-making.

(b) A New Humanities in the Postmodern University

Just as the university is the proper site of the most rigorous and systematic/methodological application of intellect to the understanding of the given world, so it is the proper site of the most rigorous and systematic/methodological application of intellect to the understanding of the cultural worlds invented by humanity. Granted this fundamental division in the objects of enquiry, it is not possible simply to allocate the first to the sciences, and the second to the humanities. But, by granting equality to both modes of enquiry and knowledge creation, the whole of reality enters the mind of the university as it is constituted outside the university by the interaction of culture with the given world through the medium of language (but also other media) and collective human action.

Jacques Derrida makes this point in a way which opens on to a critical factor in a conception of creativity in knowledge work in the humanities when he writes that ‘The limit of the impossible, the “perhaps,” and the “if,” this is the place where the university is exposed to reality, to the forces from without (be they cultural, ideological, political, economic, or other). It is there that the university is in the world that it is attempting to think’ (24). This limit or border zone has a double aspect, since it represents both the ambiguous area at the limit to thought marked out by each discipline and the excess in the object of enquiry which is not encompassed by the theories, rules, methods and conventions governing knowledge work in specific institutional settings like modern universities.

But for the university to locate itself fully in the semiotic space of culture it must widen its scope and restrain the social forces internal and external to it which would seek to control and delimit its engagements. It must recognise that human development is a cultural process enabled by fiction in the imaginative creation of possible worlds and by memory in the re-interpretation of inherited knowledge in new cultural settings. It must repay public and personal investment by rendering its knowledge work publicly accessible and by defining the ground on which knowledge policies are formed and knowledge politics are played out. It must understand itself before claiming to understand the worlds we live in.

Currently the commons, indigenous knowledge and fiction do not figure centrally in Western universities’ self-concepts, or in public policies for knowledge. But everything about the activity associated with creativity and innovation emphasises a discontinuity or rupture with the known, the customary, the repeated in knowledge and experience, in any domain of culture and society. When Derrida thinks of an institution or a quality of society (the university or democracy) in the aspect of the ‘to-come’, he is inviting engagement in creative, innovative mental work which will give expression to that which is as yet potential and of the future within a culture’s common resources of knowledge. His call for a new humanities is a call to forge a ‘humanities to-come’ which is capable of performing knowledge work according to these principles.

Conceiving of the position of the postmodern university in the social process of knowledge creation and exchange from a perspective in indigenous knowledge complements arguments based on a commons of the mind, since both place knowledge creation and exchange in the framework of the gift economy. Rauna Kuokkanen argues that ‘the academy must [reconsider] the epistemological and ontological assumptions, structures and prejudices on which it has been founded’ (125), if indigenous epistemes (systems of knowledge creation) are to participate equally in the work of the university through ‘ongoing epistemic engagement’ (120).

Engagement is premised on

the logic of the gift, which is characterized by commitment to and participation in reciprocal responsibilities … One is given a gift, which comes with a responsibility to recognize it—that is, not take it for granted—and to receive it according to certain responsibilities. When we understand the gift as an expression of responsibility towards the ‘other’, we foreground the law of hospitality. (127)

By adopting the concept of the gift as the anchoring principle of a theory of knowledge relations, Kuokkanen inverts the current dominant paradigm (which fully informs every aspect of current knowledge policy), which she describes as the

exchange paradigm, which is fuelled by self-interest, possessive individualism, and accumulation of profit (one form of which is cultural and intellectual capital) … Today’s logic of exchange is affecting the entire culture of learning, education, and academic freedom by limiting the possibility of engaging in the pursuit of knowledge … we should call the academy what it is: a corporation inhabited by privatised academics who manufacture a commodity called knowledge. (89)

Kuokannen’s argument that equality in the relation between Western and indigenous knowledges in the postmodern university can be attained only if the latter are able to participate equally in the work of the university through the ‘convergence of different epistemes’ (120) applies as well to the relations between the new humanities, the creative arts and the sciences just as much as to the relations between formal, informal and tacit knowledges, the relations between bureaucratic, commercial and academic knowledges, or the relations between cultures and their inherited knowledges.

The postmodern university as a public institution must be open to and permeated by the diversity of ways of knowing which constitute the complex society in which it is located, a locus of and focus for the intellectual and cultural energies animating social action towards enabling the coming into being of a society’s best future. Inevitably, since all conceptions of the future are politicised conceptions, such an institution will be a site for the engagement and negotiation of politicised thinking. This engagement would be premised, as Max Haiven argues, on a belief that knowledge work is a common pursuit characterised by commitment to and participation in reciprocal responsibilities (151). The concept of the gift and the concept of the commons anchor a theory and practice of knowledge relations governed by an ethic of mutual responsibility in which the asymmetry of cultures, languages, human purposes and values is the most important defining characteristic; they also anchor a theory of knowledge institutions which is grounded in discursive equality, not in the hegemony of one part of knowledge over all its other parts.

The Poem as Exemplar of Innovative Knowledge Creation

What is an available model for the kind of mental work which I have been arguing is to be performed by a new humanities, and can give a name to the postmodern university? To estrange the future as much as possible, and to reorient the university from the ground of a new humanities, my suggestion is to conceptualise the postmodern university as the Poetic University. Such a university, which would seek to place creativity and innovation in thinking at its foundations, must not only admit an equal claim to new knowledge creation from the humanities; it must grant that singular thought, founded axiomatically, theorised and informed by immersion in some aspect of humanity’s collective knowledge, can generate new possible truths.

Proposing to build the case for the importance of knowledge creation by a new humanities on poetry will undoubtedly seem incredible, including to many in the academic humanities. But I believe (while granting a bias inherent to my own context of English literary studies) that it is only by pressing as far as possible towards what locates the ground of a claim that the humanities have and can create knowledge of enduring value and innovative effect that a conception of the humanities to-come possessing equality with the claims for techno-science in its diverse disciplinary expressions can be formulated.

An opening which brings ancient traditions of thought to bear on the present can be found in the reflections of an Indian novelist and programmer, Vikram Chandra, who exemplifies in his writing the proposition that ‘The world is a web, a net, as is each human being nested within the world, holding other worlds within’ (166). These worlds for Chandra include Indian literature and literary theory, British colonial culture, modern and postmodern Western literature, and a ‘contemporary American culture of programming’ (61). As a result of attending a reading in New York by Indian poets on tour he began to explore the traditions of Indian literary theory; this dimension of his cultural inheritance provided the way to a different understanding of the relations between the two kinds of writing, particularly how far an analogy between programming and literature can be taken. Chandra quotes from the Rig Veda: ‘Language cuts forms in the ocean of reality’ (167), which points to a problem at the heart of his discussion that was investigated by ninth century CE Indian theorists of ‘the Sanskrit cosmopolis’: ‘how the effects of a language can escape language itself’ (221).

In respect of poetry, this question impels an enquiry into ‘how poetry moves across the borders of bodies and selves, and … how consciousness uses and is reconstructed by poetry, how poetry expands within the self and allows access to the unfathomably vast, to that which cannot be spoken’. For programming, he argues that emphasising traditional literary qualities like elegance ‘says nothing about the ability of code to materialize logic … Code is uniquely kinetic. It acts and interacts with itself, with the world. In code, the mental and the material are one. Code moves. It changes the world’ (221). The common factor, then, linking the writing of code with the writing of fiction is that both ‘are explorations of process, of the unfolding of connections’ (239). They make the as-yet unknown available to knowledge, giving culturally inflected forms to what is emergent in our human attempts to understand and modify the world in which we live.

Chandra’s book is a striking exemplification of humanistic thought in practice. In a move determined by my own literacy and characteristic of humanistic method, I intend to recover a text which engaged the same problematic over 400 years ago: Sir Philip Sidney’s An Apology for Poetry, the first elaborated theory of poetry in English, written at the very beginnings of the modern period and at the point of the first steps in the expansion of the British empire, in which the same issues of cultural disempowerment with which modern and postmodern humanities struggle were explored in relation to the nature and cultural standing of poetry. We can observe through Sidney’s text the articulation of a structure of relations which has been progressively entrenched by scientific and technological development and its commercial extension. Sidney noted the forces involved in terms of relations to knowledge and the role of information and communications media, in a way which was prescient not only because his argument failed in both the short and long term, but because the terms of his argument remain to be re-asserted in our present, now that the environmental and social consequences of the dominance of technocratic values and modes of thinking have become glaringly apparent.

By making his text present to us again, we can perceive what has become marginal in the official account that postmodern science-based societies give of themselves, and why public thinking and policy should become open (again) to knowledge formulated by a new humanities from its most original source in the poem.

The theory of poetry advanced by Sidney aims at the total reversal of what he notes is the situation of ‘poor Poetry, which from almost the highest estimation of learning is fallen to be the laughing-stock of children’ (96). Accomplishing this intention requires him to place poetry in the context of the other powerful modes of knowledge of his time, including religious knowledge. His argument clearly foreshadows the empirical, technocratic and pragmatic principles, conceptions and values on which modern western societies are now based, in research, government and economy. Specifically of the English, he writes that ‘Our nation hath set their hearts’ delight upon action, and not upon imagination, rather doing things worthy to be written, than writing things fit to be done’ (126). It also foregrounds the contest which persists in the academic humanities between literary, historical and philosophical studies, and offers a reason—in the derivation of the object of their knowledge work in the given world—why the latter two have been able to align themselves with the sciences and social sciences as these have evolved through the modern period, whereas literary studies (except, for example, in bibliography and literary history) have not.

He observes that ‘There is no art delivered to mankind that hath not the works of Nature for his principal object, without which they could not consist, and on which they so depend, as they become actors and players, as it were, of what Nature will have set forth’ (99-100). This is not an argument against, for example, the knowledge work of natural philosophers, or historians, or lawyers as such, or their accurate performance of the script nature presents them with, but it is an argument against its limitations, which are the limitations or ‘narrow warrant’ of nature itself. This knowledge when true is intended to ‘tell you what is and is not’ (124), which today is one foundation of the claim for the absolute priority of scientific over other modes of knowledge formation. But for Sidney, in a characterisation which is startling because it so completely runs against current conventions, the natural sciences (including history and philosophy) are but ‘serving sciences’ (104), the means to a larger end which they cannot accomplish by themselves.

All of the knowledge Sidney is considering shares a common quality: it is expressed linguistically, and in writing. So, at the heart of his argument lies a conception of writing and authorship which is capable of being a means for generating true knowledge by transcending the limits imposed on the creators of all other kinds of knowledge by the requirement of fidelity to the real (Nature), and by what we would now call disciplinary knowledge, in which the creators of new knowledge are limited by the protocols and boundaries of a discipline field; as he puts it, they are ‘wrapped within the fold of the proposed subject’ (102).

The uniquely different kind of author is a special kind of poet, conceived of as a radical source of transformative knowledge in contrast to those poets claiming authority because their writing is grounded in religious, philosophical or historical knowledge. Two classical terms, prophet and maker, capture the defining qualities of this poet’s creative knowledge work, which are summarised in two descriptions: the poet ‘borrow[s] nothing of what is, hath been, or shall be; but range[s], only reined with learned discretion, into the divine consideration of what may be and should be’ (102), and, ‘disdaining … subjection [to Nature], lifted up with the vigour of his own invention, doth grow in effect into another nature, making things either better than Nature bringeth forth, or, quite anew’ (100).

Poets are ‘makers of themselves, not takers of others’ (131); ‘whereas other arts retain themselves within their subjects, and receive, as it were, their being from it, the poet only bringeth his own stuff, and doth not learn a conceit out of a matter, but maketh matter for a conceit’ (120). Sidney is assisted in developing his conception of the poet by the Christian conception of God as maker and its consequence, that we are capable of knowing ‘what perfection is’ (101). The object of representation is ‘the Idea or fore-conceit of the work’ (101), which the poet discovers by ‘freely ranging only within the zodiac of his own wit’ (100), governed by ‘no law but wit’ (102).

This radical claim for the superiority of knowledge created poetically by a singular mind crossing the boundaries between the actual and the possible, generating new concepts by generating from the singular resources of that mind the intellectual matter from which they can be drawn, is of profound significance as a corrective to the now exclusive claims of scientific method to be the only valid source of new knowledge. Against such claims it proposes a singular origin for new knowledge in one resourceful mind exploring in thought and language beyond the limits of the collective knowledge work of those bound to Nature or the real.

This is not to privilege individualism or subjectivity over collective interests, so that the experience, sensations and perceptions of the poet are affirmed and expressed in a private and subjective space protected against the powers of the state, society and its institutions. Critical to this conception is the freedom to innovate (Sidney’s term is ‘invention’) given by following where the mind leads, and especially into the domain of what can be imagined as possible futures and moral transformations because of what thought can do and language can express. Its difference lies in the conception of humanity as not only part of nature, but also as its supplement, and it is in this kind of poetry that distinctive attributes and capacities of humanity are most fully realised.

The humanistic context which so fully informs Sidney’s thinking is integral to the specific conception of the work of poetry and the poet as he formulates it, but it is a context which postmodern Western societies need urgently to recover. Just as the singularity of the poet’s exercise of thought is a necessary condition for creating knowledge of value, so the immediate use of that knowledge is singular, in the enhancing of ‘the knowledge of a man’s self, in the ethic and politic consideration, with the end of well-doing and not well-knowing only’ (104).

Social action on the basis of this knowledge is as much a test of the quality of the person deriving knowledge from the poem, as the idea and its expression by the poem is a test of the quality of the poet’s mind. Not surprisingly, the human activity for which knowledge creation (and specifically poetry) is most important is education. As Sidney writes, ‘this purifying of wit, this enriching of memory, enabling of judgment, and enlarging of conceit, which commonly we call learning’ (104) connects the individual to social betterment through ‘virtuous action’ (104), ‘justice being the chief of virtues’ (106).

How reductive the present emphasis on education for economic development is in comparison to this humanistic conception of the person acting knowledgeably, morally and politically in the interests of achieving a more just society; that is, a society capable of achieving more of what we can know and imagine of what it means to be human in the given world.

Sidney’s conception of the ideal type of the poem and poet brings together a theory of knowledge and cognition and the linguistic and aesthetic forms which have evolved to express the work of the mind. He leaves the discovery of new knowledge of the real (Nature) to those whose work it is, drawing upon it but without conceding authority to it; instead, it is the poet who has ‘all, from Dante’s heaven to his hell, under the authority of his pen’ (111). As a resource for the work of the poet, existing knowledge is transformed in two ways, one linking imagination and fiction, the other the skilful use of artistically composed language to shape a reader’s reception of a poem. Both focus on affecting the mind by using media forms to open a mental space in which mental events can set up a critical relation to real world events.

The space constituted by the poem is the space of ‘what if?’, the space in which ‘what may be and should be’ can be explored, the space in which our humanity as the cultural supplement expanding the real can be engaged, and it is opened by employing the cognitive instruments of language and image. The poetic power of the medium must be married to a singular mind possessed by the highest conceptions of human capability for its power to produce the kinds of learning which Sidney understands to be critical in social evolution and which has the fullest achievement of human potentials in society and nature as its goal. He would surely grant the title poet to at least some of the writers of science fiction, those like Philip K. Dick or Iain M. Banks or William Gibson who employ current knowledge in the creation of fictions providing their readers with the means to think humanely forward and so contribute to shaping what may be and should be in the future worlds resulting from human thought and action.

Conclusion

Science and media technologies have shifted the boundaries between kinds of knowledge and their distinguishing characteristics as Sidney could know them. The creation of that which has never existed in nature now defines the goal of science and technology, for example, in genetic engineering, space exploration, and digital information and communications technologies. But Sidney’s fundamental contrast between poetry and the other professional domains of knowledge creation remains entirely relevant today. Throughout his essay, he holds fast to the criterion of personal moral quality as an integral component of knowledge work, locating the ultimate purpose of that work not in the end of knowledge for its own sake, or for power or wealth, but in the betterment of human society through the moral, intellectual and consequent civil betterment of humanity. If his assumption of universal moral values derived from European classical and Christian traditions has been displaced by conceptions of cultural difference and human rights, his humanistic anchoring of his discussion of the value and purpose of knowledge to the improvement of the quality of human living in social relations remains of critical importance to any consideration of the claims to be made for the humanities as knowledge of value.

As Sidney recognised, the problematic difference separating modern humanities disciplines, and the humanities from the sciences, has its origin in the fictionality and singularity of the objects of literary/media study and the refusal in the modern university or by government to admit evidence from the analysis of fictional objects as having probative value. Sidney’s humanistic argument challenges the current conception of society and its knowledge system created by the alignment of the techno-sciences, government, business, and the market. His model of poetic innovation emphasises the creation of socially transformative knowledge by the intellectual labour of free minds disseminated through media forms which stimulate imagination and desire for learning in their readers. It places realising the moral, social and intellectual potential of humanity in the foreground and its goal is the institution of the just society brought into being by the just acts of its citizens.

Sidney conceives of poetry as a techné of civilisation, a medium and mode of communication which makes available to other minds the truth-revealing thought of a singular mind located in a specific time and place. That thought, transcending the boundaries of any knowledge system or discipline, is authorised by nothing more than the singular creative intellectual action claimed by Sidney to be the distinctive attribute of the poet. For Sidney, the poet reaches mentally outside existing knowledge and into ideality; but this ‘outside’ might just as well be projected forward, as Derrida places the human knowledge project under the aegis of the emergent, the ‘to-come’, or Badiou under the aegis of the infinite. As a work of art, it has no correlative, however categorisable, until it is engaged through reading by a unique mind. It becomes a generator of meaning and knowledge when the effects of reading are communicated, the most basic mode being paraphrase or commentary, the poem translated into ordinary (prose) language. These forms of writing are not the poem itself, just as real world objects do not mean by themselves but have meaning attributed to them when they are brought into language. As Luhmann observes, art ‘depends on a supplementary linguistic mediation of its meaning’ (294; emphasis in the original). It is at this point that knowledge in the humanities comes into existence, engaged not only with works of art as events, but with all the kinds of textual events which humanity generates and which are productive of knowledge.

Brian Opie taught English at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, from 1977 to 2017. During that period, he worked tirelessly to establish an organisation that could fulfil the aims of a New Zealand humanities, most notably culminating in the founding of The Humanities Society of New Zealand/Te Whainga Aronui (HUMANZ). At its height, under Dr Opie’s direction, HUMANZ organised well-attended seminars for public servants, co-led with Creative New Zealand a cultural sector response to a major strategic futures initiative carried out by the New Zealand government in 1997 (‘The Foresight Project’), and prepared a commissioned report for government, Knowledge, Creativity and Innovation: Developing a Knowledge Society for a Small, Democratic Country (2000). Dr Opie was also influential in the success of the History of Print Culture Project in New Zealand, and the establishment of a Humanities Research Network. He was a long-term Chair of the Friends of the Turnbull Library.

Applying the methods of the humanities to the development of government knowledge policy was Dr Opie’s most treasured purpose, but he never lost sight of his teaching commitments, as will be fondly remembered by many past students who received his close and undivided attention, and he experimented continuously with teaching strategies to foster writing as a tool for learning. Dr Opie died in 2022; the following essay is a condensation of material he left unfinished.

Works Cited

Badiou, Alain. Infinite Thought: Truth and the Return to Philosophy. Trans. and Ed. Oliver Feltham and Justin Clemens. New York: Continuum, 2005.

Barnett, Ronald. The University in an Age of Supercomplexity. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open UP, 2000.

Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451. New York: Ballantine Books, 1996.

Brier, Søren. ‘Cybersemiotics: An Evolutionary World View Going Beyond Entropy and Information into the Question of Meaning.’ Entropy 12 (2010): 1902-1920.

—. ‘Cybersemiotics: Merging the Semiotic and Cybernetic Evolutionary View of Reality and Consciousness to a Transdisciplinary Vision of Reality.’ Plastir 26 (2012): 1-25.

—. Cybersemiotics: Why Information Is Not Enough. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2008.

Chandra, Vikram. Geek Sublime. Writing Fiction, Coding Software. London: Faber & Faber, 2013.

Derrida, Jacques. ‘The Future of the Profession or the Unconditional University (Thanks to the “Humanities,” What Could Take Place Tomorrow).’ Deconstructing Derrida. Tasks for the New Humanities. Trans. Peggy Kamuf. Ed. Peter Pericles Trifonas and Michael A. Peters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. 11-24.

Haiven, Max. Crises of Imagination, Crises of Power. Capitalism, Creativity and the Commons. London: Zed Books, 2014.

Hartley, John. Digital Futures for Cultural and Media Studies. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Hastrup, Karen. ‘Othello’s Dance: Cultural Creativity and Human Agency.’ Locating Cultural Creativity. Ed. John Liep. London: Pluto Press, 2011. 31-45.

Kuokkanen, Rauna. (2007). Reshaping the University: Responsibility, Indigenous Epistemes, and the Logic of the Gift. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007.

Luhmann, Niklas. Art as a Social System. Trans. Eva M. Knodt. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2000.

Nelson, Harold G. and Erik Stolterman. The Design Way: Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World: Foundations and Fundamentals of Design Competence. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Educational Technology Publications, 2003.

—. The Design Way: Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World. 2nd ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2012.

Olssen, Mark, John A. Codd and Anne-Marie O’Neill. Education Policy: Globalization, Citizenship and Democracy. London: Sage Publications, 2004.

Sidney, Philip. An Apology for Poetry; or, The Defence of Poesy. Ed. Geoffrey Shepherd. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1973.