By Erika Kerruish and Mandy Hughes

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version. doi: 10.56449/14651318

Non-metropolitan HASS students face intersecting educational challenges in a higher education landscape that duplicates entrenched inequalities already experienced in the regions. The Australian Universities Accord drew attention to the ‘compounding disadvantage’ (O’Kane et al. 266) of regional students, yet little material effort has been yet made to reverse the barriers to higher education for regional students, including the introduction, in 2021, of the so-called ‘Jobs Ready Graduate’ legislation, a government- sponsored campaign that has been directly responsible for $50,000 humanities degrees in Australia.

In this environment, the vulnerability of HASS programs in the regions has never been more evident. Across Australia, HASS programs face mounting challenges: low levels of public funding for tertiary education, increased student contributions to HASS degrees with the Jobs Ready legislation, and the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. The situation is even more dire in regional universities, with a system driven by school leavers’ demand prompting decisions to reduce HASS offerings. Moreover, metropolitan universities’ online offerings of HASS programs have persisted after the pandemic, enabling regional students to enrol in programs that provide them with greater choice. With this endangerment of HASS disciplines in regional Australia, we risk ceasing to teach vital skills and knowledge that support equity, social justice, belonging, and truth-telling essential to regional communities and students.

HASS disciplines have the potential to address disadvantage and transform the lives of precarious and marginalised students, yet despite rhetorical platitudes defending the social value of HASS more broadly, these benefits are rarely articulated and even more rarely evidenced. In this essay, we foreground regional graduates’ voices to reflect on how regional students understand how studying HASS strengthened their individual capacity and identity to shape their lives and communities. These graduate stories suggest that the critical, reflexive, and communicative skills provided by a regional HASS program assist in addressing compounding disadvantages. They reveal ways that HASS plays a key role for this cohort of students in building confidence, equipping students for employment, connecting people and ideas, and promoting social cohesion to strengthen regional communities.

Study Participants and Their Circumstances

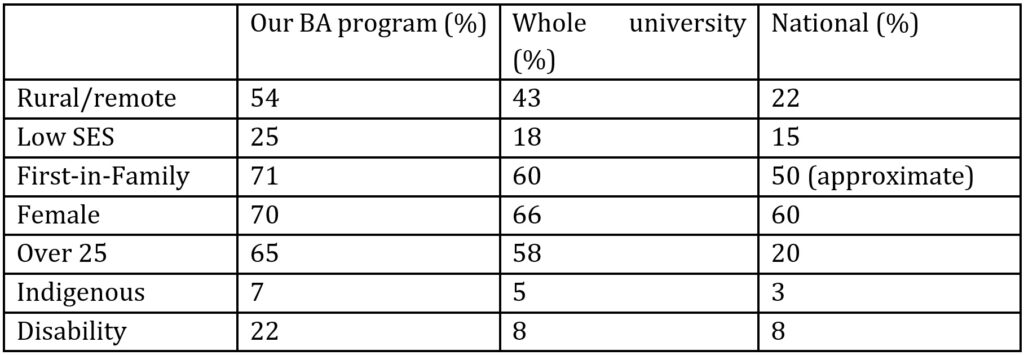

Our regional university—Southern Cross University—has two campuses located in northern NSW and one in South East Queensland. Formally established in 1994, ours is one of the most recently established universities in Australia, developing out of a College of Advanced Education servicing local communities. The university’s purpose and values include a commitment to changing lives and fostering community capacity and resilience. Forty-two per cent of our students live in rural or remote areas, and 21 per cent have low socioeconomic circumstances. According to course data, students pursuing HASS studies at our university experience high rates of disadvantage. The proportions of students in a regional or remote area, first-in-family, with low socioeconomic circumstances, or who may be female, disabled, or Indigenous, are all substantially higher in HASS than the university average. They are also higher than national figures, with the share of students in low socioeconomic circumstances already exceeding the Bradley Review’s goal of 20 per cent (DEEWR). The table below details information about the disadvantage of students in the HASS program.

Source: BA Course Data 2022, Higher Education Statistics 2022, Student Equity Data, O’Shea 2023.

Source: BA Course Data 2022, Higher Education Statistics 2022, Student Equity Data, O’Shea 2023.

Many of our HASS students face intersecting difficulties, not only between regionality, gender, low SES (socioeconomic status), Indigeneity and disability, but notably between regionality and first-in-family status, with 50 per cent of first-in-family students in the program located in rural and remote areas. With low entrance thresholds, well-supported pathway options, and flexible requirements, the HASS program enables disadvantaged groups to access tertiary education. Removing non-metropolitan HASS programs like this one, which has been and continues to be under threat, narrows the pathway to tertiary education. We argue that HASS programs in regional universities like ours are strategically valuable to address issues of equity and inclusion in tertiary education and support regional communities’ well-being and capacity building.

In 2017, students from regional and remote areas were less than half as likely as metropolitan students to attain a university qualification (Nelson et al.), while higher education participation rates have increased among Australians nationally (Gibson et al.). Geographical location, financial constraints, emotional factors, and socio-cultural incongruity have been identified as factors impeding access and completion in higher education (Nelson et al. 14-29). Multiplying disadvantage factors mean Australian university students from rural or remote areas tend to leave university early due to health or stress, workload difficulties, study/life balance, financial difficulties, or need to be in paid work (Edwards and McMillan). Regional students are more likely than their urban counterparts to live in low socioeconomic status areas, identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, study online and/or part-time, be female, be older, or have carer responsibilities (Crawford and Emery). A crucial compounding factor is the greater likelihood that regional and remote students are first-in-family students (Nelson et al. 26). This compounding factor places such students at an educational disadvantage in universities, which are experienced by them as unfamiliar and alienating environments (Luzeckyj et al.; Patfield, Gore and Weaver).

Regional universities can uniquely provide access and support to students experiencing disadvantage and living in the diverse circumstances of regional areas. Remaining in the community avoids housing, transport, and general living expenses that are higher in cities (Nelson and Picton 23-4). Students can retain their social support networks and face fewer cultural and social adjustments than if they transitioned to metropolitan areas. Gibson and co-authors explain that regional students face diverse emotional and material realities shaping their futures, so their needs and desires differ from those of metropolitan students. Importantly, they point out that this is not facilitated through a generalised notion of rurality but requires deep knowledge of local and individual conditions affecting equality in higher education if inequalities are not to be reproduced.

Although there is little research on HASS in regional universities, that which does exist suggests such universities have a first-hand awareness of disadvantaged students’ needs and are able to respond. Regional universities are equipped to ameliorate obstacles experienced by marginalised students who tend to be adversely affected by ‘systems designed for traditional students that privilege some “types” of students over others’ (Crawford and Emery 19). A lack of cultural, social, and pedagogical alignment between the traditional ideal university students and non-traditional students is starkly apparent in the difficulties experienced by first-in-family students in figuring out the ideal desired of them, a process that has often been metaphorically described as a difficult journey into the unknown (Luzeckyj et al.). The broader regional environment does not always support this journey. While non-metropolitan areas can be welcoming, close-knit, and diverse, they can also harbour conservative values and be suspicious of difference (Colvin). In this context, the social value of HASS disciplines’ teaching of empathy and communication through cultivating communication skills and knowledge of diverse perspectives is beneficial (Campion). Providing access to tertiary education for disadvantaged regional students is not about simply allocating places to fill but establishing a supportive environment (Gale and Mills) that regional universities are well-placed to provide.

In our quest to better represent and analyse regional graduates’ own experiences of and reflections on the value of their HASS education, we applied a qualitative methodology. Nine participants were recruited by purposeful and snowball sampling (a methodology described well by Onwuegbuzie and Leech). As long-term employees at the regional university, we drew on existing knowledge of HASS graduates, alum data, and discussions with colleagues to compile a list of potential participants. We emailed potential participants and provided them with an information sheet about the study. Interested participants provided informed consent, and in-depth, semi-structured interviews of up to one hour were conducted online. After transcribing the interviews verbatim, we used thematic analysis to organise the data (Berg; Perakyla). Reading the transcripts, we discussed potential themes and re-read the data, highlighting key quotes and organising the material into colour-coded themes. The findings are presented according to these identified themes.

We recognise that the small sample size could be perceived as a potential limitation of the study; however, we consider this sampling method appropriate in this instance as the enquiry had a narrow focus and produced large amounts of usable data (see, for instance Vasileiou et al.). Importantly, the sample size was not predetermined, and we were guided by the interpretative concepts of data saturation and the richness of the findings to decide when to stop recruiting. The small sample size is also considered a strength of the research as it allowed for deep engagement with the data and clear narratives to unfold (as noted in similar approaches conducted by Sim et al.)

The graduates interviewed identified with a range of intersecting equity groups. All nine graduates had been regional or remote students. Four graduates were first-in-family, six identified as being in low socioeconomic circumstances, and three were from non-English speaking backgrounds. Four students registered as having a disability, eight were mature-age, and five mature-age students were over forty at the commencement of their studies. While the participants were not asked about their gender and sexuality, one of the graduates commented that they were gender diverse, and two identified as sexually diverse. Participants have been allocated pseudonyms to preserve their anonymity.

Our account of HASS studies is formed by the stories, ideas, regions, and experiences of the graduates who participated. There are undoubtedly other perspectives that require examination, such as the significant number of students who begin but do not complete HASS programs and those who transfer into other programs. While we sought to engage with a diverse range of interviewees, no Indigenous graduates contributed to our study. It also must be recognised that our study participants faced varying levels and types of disadvantage, underscoring the need for multiple strands of research on this topic to avoid reducing regional HASS studies to a single story (Gibson et al.). The diversity of the regions means that each regional HASS program has its own particular set of challenges to negotiate.

Many of the graduates in this research achieved high marks over the course of their studies. However, many struggled in the initial phases of their tertiary education due to experiencing a range of challenges, including lacking confidence, juggling personal commitments or circumstances, lack of financial and other resources, confusion around administrative processes and academic expectations, returning to studies after an extended break or being the first in family to attend university, and cuts to offerings and courses. These challenges associated with regional study will be explored in another paper. In this essay, we have chosen to present positive examples of the significant impact of HASS courses on regional students, and conclude with a call for a maintained commitment to our transformative disciplines.

‘It colours my world’: HASS Education as Transformative

Study participants strikingly and consistently commented on how their HASS education had transformed their quality of life, using terms such as life-changing, mind-expanding, and world-opening. Comments included:

It colours my world. Like before … I feel that I was walking around seeing things in black and white and now I see them in colour. (Tess)

HASS education has opened the world to my experiences and my understandings. … I see a whole lot different. (Stephen)

It’s been an enormously rewarding journey for me personally … it’s been life-changing. (Andrew)

This life impact of studying HASS in a regional university was considered to be a profound and multifaceted personal transformation.

A sense of the world opening up was often accompanied by increased confidence, voice, agency, and connectedness. Tess and Beau described how their studies increased confidence and connection:

It opened up my world. It gave me a sense of myself as interesting, as valuable as someone I could learn to be proud of, when at a time in my life before that, it had a lot of isolation and shame and disconnection and loneliness. (Beau)

I’m so much more aware and more confident … than I used to be. (Tess)

I am interacting more with other issues and people that I normally wouldn’t have before. (Tess)

Patricia and Stephen commented on how they had gained a sense of their voice’s value:

I didn’t have a lot to say prior to studying, so it really increased my sense of: hey, you’d better listen to me; I’m someone worth listening to. (Patricia)

It’s provided voice, it’s provided my understanding of that agency and how agency can be used. (Stephen)

Stephen noted the relationship between voice, belonging, connection and self, commenting that his studies led him to

developing voice and developing connection and a sense of belonging, which is again linked to a sense of self-worth, a sense of value.

Bernard stated that his studies allowed him to respond to questions about

where do I fit in here and how can I contribute to addressing some of these stark injustices that I witness.

Beau said that their degree helped build

a sense of myself that was resilient and that was valuable and that was connected into the communities that I belong to.

Increased confidence was interwoven with the ability to interact with others and exercise agency.

Several graduates commented that comprehending their social, political and ethical landscapes made them more open and questioning. Tania and Tess reflected:

I’m much more open to questioning where I fit in my ideological beliefs, and also my political beliefs … to being flexible in that and not so rigid and fixed. (Tania)

It’s definitely stripped away a lot of judgment. (Tess)

The life transformations wrought in studying HASS included creating further study and employment opportunities. Comments included:

So I enrolled at the age of 38, I think, or 39, and 10 years later I came out with a PhD. So it was pretty, pretty transformative. (Andrew)

I pretty much got the first graduate position that I applied for. (Tania)

I had no employment options prior … and I was actually engaged with employment before I completed my undergrad. (Stephen)

This included equipping students with a variety of work skills:

I do a bunch of freelance work, but it’s all very much based on the skills that I learned in that degree. (Beau)

[HASS studies] allowed me to be adaptable. The ones [skills] that allowed me to sort of move into a position and figure it out. (Sara)

The flexibility of the skills acquired during HASS studies enabled them to take up and succeed in different employment opportunities.

The skills Andrew, Stephen, Sara, Beau and Bernard acquired supported them to build substantial, long-term careers. Beau commented that their degree and their lecturers’ support

enabled me to really sustain my advocacy and activism across the last ten years or more now since the degree and have a really kind of grounded sense of social justice work and what it looks like for the long haul and how to bring people along with me.

Bernard stated that the skills and knowledge used in his employment

are things that I was exposed to as part of my degree and learned to value.

Andrew said,

I started working at [NGO] as a volunteer, so there’s a legend that at [NGO] that I started working as a volunteer and ended up being the CEO and that’s literally what happened.

The transformative effects of HASS supported research participants for decades after their study, guiding work choices and sustaining their careers and their communities.

‘Step outside of your experience’: Benefits of HASS Studies

HASS disciplines built graduates’ understanding of their own and others’ situations, whereby epistemic change was bound up with personal transformation in processes understood to be central to HASS’s broader value. Beau commented that HASS

enabled me the space and the time as a young person with a disability who’s queer and trans and coming from that kind of that socioeconomic, disadvantaged space at home to start to contextualise myself and my identities in my life and some of the barriers that I was encountering not as individual or personal problems, but as systemic issues that have very structural and human rights centred solutions to them.

For Stephen, HASS enabled the investigation of his relationship to society:

I wanted to delve into the study of society, the science of society, to try and understand that disconnect between myself and society.

Similarly, seeking to understand her own experience led Tania to understand how social and cultural positioning shaped people’s lives. She commented that after experiencing racism:

I realised that there was a lot of inequity and … a lack of understanding and a lack of nuance in terms of intersectionality and different experiences and different world views, and that kind of got me on a bit of a path to wanting to educate myself further to advocate for myself. … to learn more about social science rather than an individual psychological view of the person that’s the problem, but more of a holistic worldview of how society impacts different people.

Reflexivity in the context of HASS studies of society, politics, and culture meant that participants understood not only their own lives but also others’ circumstances better.

Several graduates thought HASS studies developed empathy and sensitivity to other people’s perspectives and promoted social cohesion through developing an understanding of how society interacts and knowledge of the human experience. They commented:

It [studying HASS] would just stop so much bigotry. (Tess)

the skills that you learn in humanities are understanding the world and having empathy for people. (Sara)

study has opened my eyes into looking at all of the different perspectives. … understanding context around things and different voices and who gets heard and who doesn’t get heard. (Tania)

if you don’t have those fundamental understandings of how society interacts and how they impact each other in different ways then social cohesion is not going to really happen. (Bernard)

Several participants noted that their study took them beyond their own life experiences:

[Humanities] requires that you step outside of your experience. I had never read a book by an Indigenous author until I went and studied at [name of university]. I had studied high school…. all of the English courses. (Sara)

It covered globalisation and then Indigenous inequality … gender and sexuality, that was really great. And these are all things that … I knew nothing much about really. (Zoe)

Tania stated that class dialogue and diversity contributed to learning beyond one’s experience:

I really like having the different generations and a wide variety of experiences and opinions about things, because I think that really engages me in thinking outside of a bubble and thinking outside of my own experience.

Moving beyond their own life experience developed participants’ understanding of culture, society and the life experiences of others. This included people’s disadvantages and how they might be addressed. Beau commented that HASS

Enables us to think about the ways in which we need to challenge and change society to be more equitable and accessible to people. … really important social change work.

A greater comprehension of diverse people’s circumstances and challenges learned in studying HASS in the regions was seen to generate impetus towards positive social change.

Bernard articulated how HASS exposes students to new ideas and vocabularies in a critical, dialogic environment:

you’re challenged to think and converse with others and disagree and have the ability to make sense of the world. … the idea of having concepts and terms and words to express something that you might have felt but really hadn’t had a way to articulate beforehand.

Participants found the theories and critical thinking taught in HASS to be a powerful resource, stating:

Those theories explain to me a lot about human behaviour, human understanding. And I think some people engage at a much deeper level if it’s about those theories. (Stephen)

[Studying HASS] enables you to critique what other people or what papers are talking about. (Patricia)

They help us help us to examine ourselves and the societies that we live in, the world that we live in critically. (Bertrand)

Zoe welcomed the open, questioning of HASS, commenting,

It’s not like I’ve got to learn parrot fashion. … It’s you’re actually learning. And it’s really interesting.

The critical, theoretical perspectives taught in HASS supported the transformation of participants’ relationships to themselves and their non-metropolitan communities.

‘Each community has its own challenges and barriers’: Community and Regional Perspectives

Expanding on the view that studying HASS cultivated tolerance and increased social cohesion, the graduates commented that this was especially valuable in a regional area. Tania stated,

Because if you’re in a regional area, you’re less likely to be exposed to different sections of society… you’re less likely to be exposed to disparity in society.

Exposure to HASS disciplinary knowledge and sharing diverse lived experiences is especially beneficial in more homogenous communities. Participants observed how studying HASS in regional communities can contribute to creating new regional perspectives that embrace difference, for example:

HASS education is one of the most valuable contributions to a regional community… it removes a lot of prejudice from community, it instils a lot of tolerance through understanding, through that education. It also opens that process of critical thought, respectfully asking questions or respectfully challenging a position. (Stephen)

Participants found that their HASS studies cultivated an ability to engage with a variety of different people and groups in a community.

An additional benefit of a regional HASS education is that it is place-based and tailored to the specific needs of students and communities. Study participants reflected on how their HASS education made them better equipped to respond to specific local issues, such as coal seam gas exploration, gaps in services or advocacy needs. Participants commented on the unique way they could use their HASS education to inform and respond to local issues:

It’s very localised because, obviously, each community has its own challenges and barriers. (Zoe)

You could drill it down into all sorts of areas like health, the understanding of how different sections of Australia don’t have as much access to free and readily available access to health than other places in the country and how important it is to engage in fixing that problem. Or advocating or getting involved in politics, engaging with the politicians and understanding the reasons why it’s important for everybody to be engaged in how society works. (Tania)

Additionally, participants commented on the specific way regional universities engage with HASS knowledge to respond to local contexts:

Being in a regional space, it’s a whole different concept to social science than studying it in the bubble of the city. Because there’s opportunities to engage in different types of disparities in society in a regional space. (Tania)

There’s more of an opportunity at regional universities to do really innovative and even ground-breaking stuff because we’re not as constrained, perhaps, as we might be at metropolitan universities. And when it comes to the learning, especially as an undergrad, I think that community engagement and experiential learning in particular were the key bonuses for me of being at a regional university. (Bernard)

HASS offerings in regional areas are often deeply committed to community engagement and actively seek to connect students to local and educative arts and cultural and social opportunities. Numerous examples were provided by participants, for example:

We would go out and engage with the local community and the kind of institutions that are part of that community and then utilise that to really think about power and identity and some of the key topics that we were covering as part of that course. So it felt like our studies were really connected into the geography of the place and the history of the place in terms of thinking about white colonialist history and Indigenous history in a way that I haven’t seen replicated in units of study in other universities, particularly in metro ones. (Beau)

Being at a regional university really allowed me to learn in a way that I felt was much more connected to and embedded with the local community through things like field trips, through [local] guest speakers. (Bernard)

The pedagogy and content of the University’s HASS teaching was embedded in the local area’s issues, history and people.

Being able to study HASS ‘in place’ in your non-metropolitan home can also foster a sense of belonging that can strengthen individuals and communities. Patricia commented,

You’re part of a community, and there’s a lot being discussed these days about community. I just think it’s so good for your sense of belonging if you’re attending a local university can socialise with those people that you meet.

The ability to remain in regional homes, connected to social and support networks, is vital for those experiencing multiple barriers to study.

Andrew commented that having employable HASS graduates trained in regions was essential:

it can be difficult to recruit high-level skills and experience in regions, and so I think it’s really important that we are able to train in situ where they live and not have to go necessarily to the city to get a high-quality education. The contexts around regional service delivery, regional work are pretty important. People in metropolitan areas and in cities don’t always understand the barriers and the context that exist in regions in terms of service delivery.

A regional HASS program provides a knowledge base and critical and reflective skills vital to successful regional projects and service delivery.

All participants agreed that studying HASS in non-metropolitan areas is vital to regional community capacity building. The knowledge, confidence and opportunities provided for regional HASS students are instrumental in building local community capacity in various ways, including contributing to the intellectual and cultural life of the regions. Participants noted:

something happens in your mind and body that gives you the strength and agency to participate in community and conversation. (Patricia)

prior to university education I did not communicate very well with individuals or the community. I had no interest in participating in community. It’s only through the process of education that I began to understand what community actually was and the value of community. (Stephen)

Study participants said that a HASS regional education can enable marginalised voices to be heard:

My HASS education more broadly sensitised me to the importance of actively asking myself which perspectives am I not hearing. Who is not here? And to seek them out and to do that not only as an educative process for myself but to do that as part of my work…whether it comes to gender diversity, whether it comes to disability, whether that comes to diversity of race and ethnic backgrounds and the value of those diverse experiences. (Bernard)

Sara said that having HASS on campus was especially beneficial in disadvantaged communities because it provides a locus from which inclusive views can emanate

in communities that are less prioritised, less engaged with, less funded, less invested in. … the social problems like racism, sexism, all these sorts of things. … the knowledge of how these things work … can still sort of ebb out into an environment. … just being in an environment where the knowledge of gender equality is around you can affect the way that you think.

HASS programs in the regions are a significant resource for circulating positive understandings of diversity and supporting inclusivity.

Andrew commented that local HASS training developed community resilience so they could respond to the diverse, complex problems in regional communities:

Regional communities face the same problems as any other community in Australia that need to … And then regional communities add to those problems some extra complexities of isolation, relative isolation and smaller populations and smaller pond to fish in when it comes to finding talent, things like that. And so it’s profoundly important that HASS courses offer really strong and robust training to people who live in regions, so that regions and regional areas can be self-supporting and resilient… there are people living locally who belong in those communities. They haven’t been flown in from elsewhere because that can often end up being disastrous … these types of courses are profoundly important to resourcing our communities, to grow and to be strong.

Locally educated HASS graduates have insight into the social dynamics, complex issues and potential solutions in regional communities, making them essential to community capacity building.

Why We Need HASS in Regional Universities

There are mounting cuts and threats to HASS programs at our and many other regional universities, with increased student contributions, reduced programs and degrees, and an expansion of online offerings by metropolitan universities. Our findings underscore the benefits that risk being lost in reducing support for regional HASS programs embedded in their communities.

The graduates’ circumstances and comments correlate with previous research on the intersecting and layered barriers to study faced by regional students (Edwards and McMillan; Nelson and Picton; Crawford and Emery). Interviewees found the University’s HASS program life-changing and transformative for their disadvantaged situations. Such effects of HASS study have been noted by research on how higher education can be life-altering for disadvantaged students, reconfiguring self-understanding, economic circumstances, and social and community relationships (Hyland and Syrnyk; Gervasoni, Smith and Howard). While it has previously been shown that HASS graduates in Australia readily find employment (QILT 11), our participants add a fuller picture of the life significance and the sustained individual and community effects of such employability in the regions. As Andrew’s comments made clear, educating HASS graduates locally in the University’s regions is crucial to making their communities resilient. Locals are familiar with the complexity of specific regions and uniquely able to provide creative solutions to regional problems, as noted by previous research (DEEWR 259-60).

The dialogic and self-reflexive learning in the HASS program enabled Tess, Beau, Tania and Patricia, participants who were insecure about attending university, to situate themselves in relation to what they were learning. Incorporating self-reflexive meaning-making processes in learning about social, cultural, and political landscapes underpinned the program’s transformative power. Interviewees were provided with an opportunity to relate their life experiences to broader social and cultural contexts via texts and classroom and community-embedded learning. The beneficial effects of this have been noted by other research on HASS programs addressing disadvantaged students (Gervansconi, Smith and Howard 495; Hylan and Synyrik). Participants conveyed that their studies cultivated a sense of agency and the capacity to direct their lives in ways that had long-term meaning and value. It provided them with a valuable suite of ideas, theories and skills.

All study participants emerged from their learning process with knowledge beyond their life experience and a stronger relationship with other individuals and communities. They considered HASS to cultivate social cohesion, empathy, acceptance of difference and inclusivity. This aligns with Gervansconi, Smith, and Howard’s findings that the regional Clemente Humanities Program provided a journey of self-discovery for students, which increased social participation and tolerance through gaining knowledge and contact with diverse people. Our interviewees’ experience further accords with research concluding that the humanities have social value because they train students to see issues from multiple perspectives and develop communication skills that enable the circulation of different viewpoints (Holm, Jarrick and Scott 18-19; Campion). The study suggests that HASS plays a significant part in how regional universities benefit regional areas as ‘growers of human capital’ and as ‘institutional contributors to the social and cultural fabric of local communities’ (Eversole 910).

Conclusion

Across their differences, our students conveyed powerful stories of transformation and regional community engagement and capacity building. They considered HASS education an indispensable resource for building social cohesion and resilience in their communities. Their studies had a positive, profound and long-lasting effect on their wellbeing. A change in knowledge and skills coincided with personal transformation, which positively affected their relationships with others and community participation. Our HASS program supported this process by encouraging graduates to situate themselves self-reflexively in social, cultural and political landscapes through texts, theories and community-embedded learning. While specific to our university and regional area, the graduates’ narratives of empowerment and belonging show the profound cost of ceasing to support HASS programs in the regions.

Erika Kerruish is a senior lecturer in cultural studies and the Bachelor of Arts course coordinator at Southern Cross University, Australia. Her research examines perception, affect and critical analysis in digital technologies such as video art, virtual reality, and social robotics. She believes the Humanities bring vital perspectives to contemporary social and cultural debates.

Mandy Hughes is a senior lecturer in sociology and social science course coordinator at Southern Cross University, Australia. Her research interests include refugee studies, social inclusion, community studies, sociology of health, and creative research methods. Mandy has a strong commitment to the power of education to foster critical perspectives that value social justice and reduce inequality.

Works Cited

Australia Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR). Review of Australian Higher Education: Final Report [Bradley review]. Canberra: DEEWR, 2008. <https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A32134>.

Berg, Bruce. Qualitative research methods. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2009.

Campion, Corey. ‘Whither the Humanities?—Reinterpreting the Relevance of an Essential and Embattled Field.’ Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 17.4 (2018): 433-48.

Carroll, D. R., and I. W. Li. ‘Work and Further Study After University Degree Completion for Equity Groups.’ Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 44.1 (2021): 21-38. <https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2021.1988841>.

Crawford, Nicole and Sherridan Emery, S. ‘“Shining a Light” on Mature-Aged Students in, and from, Regional and Remote Australia.’ Student Success 12.2 (2021): 18-27. <https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.1919>.

Colvin, Neroli. 2017. ‘“Really Really Different Different”: Rurality, Regional Schools and Refugees.’ Race, Ethnicity and Education 20.2 (2017): 225-39.

Edwards, Daniel and Julie McMillan. Completing University in a Growing Sector: Is Equity an Issue? Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research, 2015.

Eversole, Robyn. ‘Regional Campuses and Invisible Innovation: Impacts of Non-traditional students in “Regional Australia”.’ Regional Studies 56.6 (2022): 909-20. <https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1899156>.

Gale, Trevor, and Carmen Mills. ‘Creating Spaces in Higher Education for Marginalised Australians: Principles for Socially Inclusive Pedagogies.’ Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 5.2 (2013): 7-19. <https://doi.org/10.11120/elss.2013.00008>.

Gervasoni, Ann, Jeremy Smith and Peter Howard. ‘Humanities Education as a Pathway for Women in Regional and Rural Australia: Clemente Ballarat.’ Australian Journal of Adult Learning 53.2 (2013): 253-79. <https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1013656.pdf>.

Gibson, Skye et al. ‘Aspiring to Higher Education in Regional and Remote Australia: The Diverse Emotional and Material Realities Shaping Young People’s Futures.’ The Australian Educational Researcher 49.5 (2022): 1105-24. <https://doi-org.ezproxy.scu.edu.au/10.1007/s13384-021-00463-7>.

Given, Lisa, ed. ‘Purposive Sampling.’ The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2008. 697-8.

Holm, P., A. Jarrick and D. Scott. 2015. Humanities World Report. Springer Nature, 2015.

Kuttainen, Victoria. ‘The Promise and Betrayal of Arts and Culture in Regional Australia.’ Overland 13 February 2023. <https://overland.org.au/2023/02/the-promise-and-betrayal-of-arts-and-culture-in-regional-australia/>.

Lambrechts, Agata A. ‘The Super-disadvantaged in Higher Education: Barriers to Access for Refugee Background Students in England.’ Higher Education 80.5 (2020): 803-22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48736449.

Luzeckyj, Ann et al. ‘Being First in Family: Motivations and Metaphors.’ Higher Education Research & Development 36.6 2017: 1237-50. <https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1300138>.

Nelson, Karen, Catherine Picton, Julie McMillan, Daniel Edwards, Marcia Devlin and Kerry Martin. Understanding Completion Patterns of Equity Students in Regional Universities. Perth: National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, 2017. <https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/app/uploads/2017/06/Nelson-Completion-patterns.pdf>.

O’Kane, Mary et al. Australian Universities Accord Final Report. Australian Government, 2024. <https://www.education.gov.au/accord-final-report>.

O’Shea, S. ‘“It Was Like Navigating Uncharted Waters”: Exposing the Hidden Capitals and Capabilities of the Graduate Marketplace.’ Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 45.2 (2023): 126-39. <https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2023.2180161>.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J., and Nancy L. Leech. ‘A Call for Qualitative Power Analyses.’ Quality and Quantity 41 (2007): 105-21. <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-005-1098-1>.

Patfield, Sally, Jennifer Gore and Natalie Weaver. ‘On “Being First”: The Case for First-Generation Status in Australian Higher Education Equity Policy.’ The Australian Educational Researcher 49.1 (2022): 23-41. <https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00428-2>.

Perakyla, Anssi. ‘Analysing Text and Talk.’ Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Ed. N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln. London: Sage, 2005. 869-86.

Quality in Learning and Teaching (QILT). Graduate Outcomes Survey, 2023. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Education, 2022.

Sim, Julius, Benjamin Saunders, Jackie Waterfield and Tom Kingstone. ‘Can Sample Size in Qualitative Research Be Determined A Priori?.’ International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21.5 (2018): 619-34. <https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1454643>.

Vasileiou, Konstantina, Julie Barnett, Susan Thorpe, and Terry Young. ‘Characterising and Justifying Sample Size Sufficiency in Interview-based Studies: Systematic Analysis of Qualitative Health Research Over a 15-year Period.’ BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (2018): 1-18. <https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7>