By Riccardo Welters and Jonathan Kuttainen

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version. doi: 10.56449/14619327

In an environment in which budget limitations force governments to choose between a selection of public services for preferential funding, public-service providers are under pressure to demonstrate ‘value’, especially if they require public funding. To justify the direction of public funding, governments mandate providers to conduct cost-benefit or social return-on-investment analyses to demonstrate the return on a dollar invested in a public service. This creates an environment in which providers are required to engage in an exercise to gage the dollar-value of the public service.

While universities are publicly funded institutions in Australia, the mandate to demonstrate ‘economic value’ has encountered considerable resistance, especially from HASS scholars.[1] The issue is not constrained to the Australian context either. There is a substantial body of diverse research from various humanities and social sciences disciplines addresses many concerns related to valuing the humanities and the complexities of such approaches within their national contexts over the last several decades. In fact, there exists a broad literature that draws on multiple perspectives to establish the intrinsic value of HASS for both society and individuals who pursue them. Some reject the notion of a valuation exercise in public-service provision outright. Others challenge the process engaged in a valuation exercise, asking for example, who is to determine what is of value and value to whom?

To ensure that the concerns raised by scholars regarding the valuation of HASS scholarship and teaching are not downplayed, this essay will first consider key critiques and public benefits identified in the research. The aim is to characterise the overall thrust of the arguments related to valuation and impact analysis.

Following this, the essay will focus on proposed methods that can generally be used to attribute value to the provision of public services, specifically applied to regional tertiary humanities and social science sector and its attempts to engage in the valuation exercise to examine impact on individuals and communities, particularly among those who hold humanities degrees. This perspective is particularly relevant in regions where the value of humanities education may be less recognised or appreciated. While this analysis emphasises personal and communal benefits, it is important to acknowledge that other forms of value—such as contributions to cultural enrichment—are beyond the scope of this article. As we will see in this essay, HASS scholars would be well served, within the current marketised environment, to proactively engage with these discussions, especially if they wish to influence market-driven discourses.

Current Practices: Valuing Tertiary Humanities and Social Sciences

The current framework for evaluating academic outputs of the public sector is often traced back to the UK in the 1980s, under the Thatcher government (see, for example: Belfiore and Bennett; Bulatis; Martin). This environment and period marked a decisive shift towards the neoliberalism of Milton Friedman’s market-oriented approaches within higher education and the public sector, emphasising managerialism and the use of performance metrics (Marginson 271). It was during this era that the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) was introduced (with the first RAE conducted in 1986), aimed at assessing the quality of research within British higher education institutions, in order to inform funding decisions. This initiative reflected a broader agenda to increase accountability and efficiency in the public sector. In 2014, the RAE was replaced by the Research Excellence Framework (REF) impact assessment, a change spurred on by the increasing emphasis on impact, increasing expectations of transparency, and heightened expectations that publicly funded research should have application and value to the wider community. Some of these increasing pressures were related, at least in part, to strains on the public purse in the fallout of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. The importance of demonstrating research impact beyond academia, and expectations of ‘value-for-money’ consequently became prominent and widespread (see, for example: Bulaitis; Chiang; Chubb and Reed; Holbrook; Martin; Smith). These changes have contributed to the growing ‘impact agenda’.

Their historical roots notwithstanding, the proliferation of ‘impact analysis’ and economic value approaches to measuring the outputs, social benefit, value-for-money and other determinants of ‘value’ are now evident throughout many discussions of the tertiary humanities and social science sector beyond the UK, including the United States, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia (see, for example: Hazelkorn et al.; McCormack and Baron). Despite—or perhaps because of—the move toward the impact agenda, HASS scholars have strongly resisted the shift towards economic valuation. As Benneworth (2015) poignantly states,

Humanities and the arts are so profoundly different as academic pursuits from science, engineering and technology, that this difference casts them with a mark of Cain, destined to peripherality and suffering. (3)

Despite the HASS disciplines’ commitment to advancing societal good, HASS scholars often prioritise interpreting, influencing, and shaping society, preserving cultural heritage, and fostering self-understanding in various contexts, rather than producing immediately ‘usable’ results. Humanities studies also tend to prioritise qualitative and interpretive approaches over quantitative and positivistic methods typical of the sciences. Moreover, truth claims in the humanities are not universally verifiable like those in the natural sciences (Benneworth 6; Bulatis 2; Small 23). Consequently, many argue that the impact of HASS should not be evaluated merely in terms of ‘return on investment’ or value-for-money expectations; many also note that while scientific contributions may be more measurable, they are not inherently more valuable or relevant (Doidge et al. 1129; Olmos-Peñuela et al. 67). HASS defenders who take a version of this position tend to argue that the imposition of impact and valuation demands on HASS is an unsuitable application of scientific metrics.

Although the diverse disciplines within HASS foster a variety of perspectives in their response to arguments for and against economic valuation of humanities and social sciences, consistent patterns and themes are demonstrably evidenced in the extensive body of literature on this topic. They challenge the comparison of HASS scholarship with natural science disciplines, highlighting a fundamental incongruity between HASS values and prevailing impact metrics (see, for example: Archambault and Larivière; Reale et al.). Additionally, they point out the inherent challenges in defining and quantifying impacts and criticise the excessive reliance on econometric models as a standard of relevance (Belfiore and Bennett; Benneworth).

HASS scholars highlight several critical flaws in impact analysis that lead to perverse outcomes, particularly the funding models that disproportionately favour STEM research. These models encourage a focus on projects that promise immediate benefits and clear market results, often at the expense of research with potentially greater long-term significance and intellectual depth. This emphasis on short-term gains and marketable outcomes constrains the scope of research and neglects more complex, nuanced studies that could offer substantial contributions over time (see, for example: Bulaitis; Doidge et al.; Pedersen et al.; Pike). There is also the concern that impact assessments encourage a utilitarian view of research, where the value of academic work is judged primarily by its direct contributions to economic growth or to addressing specific societal problems. This perspective can undermine blue-sky, pure research and critical studies, which tend to predominate in HASS, which do not have immediate practical applications but are vital for the comprehensive development of knowledge. Other arguments against imposing these kinds of valuation and impact assessments on HASS highlight the way the pressure to produce measurable impacts can limit academic freedom, pushing scholars to pursue research topics that are likely to yield quantifiable outcomes rather than those driven by curiosity or societal necessity (see, for example: Chubb and Reed; Doidge et al.; Holbrook). These and many other concerns are consistently raised in discussions aiming to moderate the expectations of impact assessments and to call into question the relevance and insistence on a direct return on investment for funding research and education in the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences.

Despite the expressed concern by many scholars on the possibility and relevance of economic valuation of tertiary HASS research, an increasing number of efforts have begun to engage in valuation exercises, especially in regard the valuation of HASS teaching, leveraging the expertise of major economic and consulting firms to translate HASS education into economically understood terms. Notably, these influential policy research and consulting entities significantly shape public policy through their research and strategic consulting services, impacting government decisions across various sectors, including higher education. However, they face criticism for potential conflicts of interest, concerns about the objectivity, quality, and methodological rigor of their research, as well as the influence of funding on academic priorities. One of the earliest such attempts, commissioned by the University of Cambridge, RAND Corporation’s Report (Levitt et al.) recognises the challenges of assessing impacts in HASS but makes suggestions for how economic modelling might be adjusted to do so. It suggests modifications to the Payback Framework to evaluate scholarly impacts through diverse means. These include both research measures that contribute to useable resources or influence policy, and education measures that value educational outcomes and enhancing public engagement. The report’s case studies, in particular, highlight the strength of HASS in these areas (Doige et al. 1132; Levitt et al. 46).

KPMG’s 2018 (Parker et al.) report Re-imagining Tertiary Education: From Binary System to Ecosystem is another such attempt to highlight educational impacts. While not focusing on HASS exclusively, it highlights the importance of HASS to building and maintaining civil society and models value statements for forms of education like HASS that are not ‘purely instrumental but do have important social purpose’ (17). Another is Price Waterhouse Cooper’s (PWC) Lifelong Skill report in 2018. It makes passing reference to HASS by emphasising the importance of soft skills such as critical thinking, open-mindedness, and both written and oral communication—skills highly valued by employers. In a report commissioned by the UK’s Arts and Human Research Council (AHRC), PWC conducted an economic valuation that foregrounded both the economic and civil capital of humanities research and teaching; noting that excellence in humanities research drives tertiary jobs and income-generating student places, as well as cultural industries, suggesting a £1.10 return for every pound invested in the humanities (34).

In the Australian context, the Deloitte Access Economics 2018 Value of the Humanities report is the most comprehensive consultancy-generated investigation into the value of HASS. It, too, emphasises the value of HASS education. The report emphasises the significant benefits HASS graduates bring to the labour market, particularly highlighting their transferable skills such as critical thinking, communication, and problem-solving. These skills, vital in addressing complex societal challenges, align well with the needs of non-market industries like the public sector and enhance economic productivity through higher labour force participation and wage premiums they can command. Furthermore, Deloitte Access Economics argue, humanities education contributes to business practices and governance reforms, underlining the economic impact and adaptability of humanities graduates have in a rapidly changing job market.

The Deloitte report foregrounds the way that both humanities research and teaching in the tertiary sector plays a crucial role in society by enhancing awareness, encouraging engagement, and shaping both policy development and cultural change. Both HASS research and teaching, it argues, lead to significant societal benefits, including improved health outcomes, policy reforms, and cultural innovation. These contributions are often amplified through media exposure and collaborations with other research entities and policy-making bodies, further extending the influence and reach of humanities research in addressing contemporary challenges and enriching public and academic discourse.

The Deloitte report also underscores the substantial benefits that humanities graduates bring to the workforce and communities, highlighting their high levels of job satisfaction, which at 86 percent surpasses all other industries. Additionally, these graduates exhibit a greater propensity for workforce participation, standing 3.8 percent above the average (Deloitte 7). Furthermore, Deloitte demonstrates the impact of significant pro-social values in humanities graduates, which are evident in their high levels of civic engagement, including the values of trust and trustworthiness, active participation in voting and political arenas, and commitment to volunteerism. These attributes not only contribute to graduates’ personal well-being but also enhance their communities.

Although the Deloitte report acknowledges changes in the labour market, it provides insufficient evidence to demonstrate how these shifts are influencing hiring practices within, for example, major industries, where many HASS graduates find employment. This gap highlights the necessity for more detailed research to examine how and whether large institutional employers are adapting their recruitment strategies to capitalise on the unique skills of HASS graduates. Understanding this alignment is an opportunity for assessing impact of these graduates in key sectors of the economy. Furthermore, the Deloitte report was commissioned for Macquarie University, and while it attempts to adjust for factors like regionality and remoteness, no existing study yet exists that focuses on the value of HASS education in regional Australia.

In summary, the discourse surrounding the valuation of HASS contrasts their intrinsic worth, that is, their inherent value and value in their own right, against the need to express their value in economic terms in ways that are typically required by funders, policymakers, stakeholders, and increasingly by governments. While the reluctance of HASS scholars to adopt economic metrics is understandable, we argue that HASS sector must move beyond its entrenched reluctance to engage with the tools of economic analysis and embrace their economist colleagues. Even international consulting firms have attempted to provide analyses comprehensible to policymakers. This leaves the valuing of the regional humanities, which appear to be under increasing threat (Kuttainen) particularly vulnerable.

In an era focused on metrics of economic development and societal impact, it is imperative for HASS to proactively employ economic measures to advocate for the support needed to ensure these disciplines thrive and contribute meaningfully to public policy, especially in regional communities. It serves the interests of the community, students, and scholars to do so. Active data collection initiatives in Australia, such as the QILT research, highlight the significance of these metrics. So too can research reports such as the Mapping Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences in Australia developed by Graeme Turner and Kylie Brass (2014). Implementing such approaches can substantially influence future policy decisions, benefiting HASS scholarship, students, and the community at large. This approach can secure their relevance and sustainability by aligning their intrinsic values with quantifiable impacts that resonate within current policy frameworks, making them comprehensible to policymakers, university administrators, and industry leaders.

Attributing Value

Much of the critique in the HASS sector on economic valuation focuses on the question whether its output can be monetised. This leaves other elements of the valuation exercise (for example, value attribution, spatial heterogeneity and non-person related, inherent value) aside. We will explore the importance of these elements to demonstrate alternative methods for attributing value that have not been considered.

The HASS sector intends to understand the world and our place in it through research and teaching. To illustrate value attribution methods, we focus on the second component, the economic value of which, is difficult to gage. This valuation process contains two elements (value creation and value attribution), which both cause empirical challenges for at least two reasons.

First, as alluded to already, much of the value creation is inherently complex to quantify economically. This complexity often leads researchers to exclude complex-to-measure value from the valuation analysis, de facto assuming complex value has zero or limited economic value. The literature is quite explicit about this concern (see, for example: Olmos-Peñuela et al; Benneworth; Bate).

Second, even if we acknowledge the first concern and the complexities of economic valuation applied to HASS scholarship, we must select appropriate methods to establish to what extent identified value creation is attributable to HASS education, which is the gist of this essay.

It is important to note that the approach taken here highlights that students in the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (HASS) are Bachelor of Arts (BA) students. Given the constraints faced by regional universities and their smaller course offerings, it is common for BA students to pursue a broader range of disciplinary studies to fulfill core and elective course requirements for degree completion. For the purposes of the proposed methodology, a HASS student within the Bachelor of Arts may also be enrolled in classes such as journalism, marketing, business, law, education or social work.

From a theoretical perspective value created by HASS education is (by definition) attributable to HASS education, hence there is no need to differentiate between the two concepts. However, an empirical setting may obfuscate the boundaries between both concepts.

As a running example in this section, we focus on a HASS student completing a Bachelor of Arts degree through which they will augment their critical thinking skills (typically measured as a stock variable at degree completion), which, as highlighted earlier (AHRC 15; Deloitte 8; Hazelkorn et al. 61) is a common claim of universities offering a Bachelor of Arts degree.[2] Equally relevant as the question how to measure the economic value of those skills (value creation), is the question to what extent these skills are attributable to degree completion (value attribution).

Assuming they are fully attributable to degree completion, for example, implies that the student:

a) had no critical thinking skills before they commenced the Bachelor of Arts and,

b) would not have developed critical thinking skills through other pathways, which they may have traversed, had they not completed a Bachelor of Arts.

Both assumptions are likely untenable and may distort the valuation exercise even if we manage to establish what elements produce and how to measure that value economically.

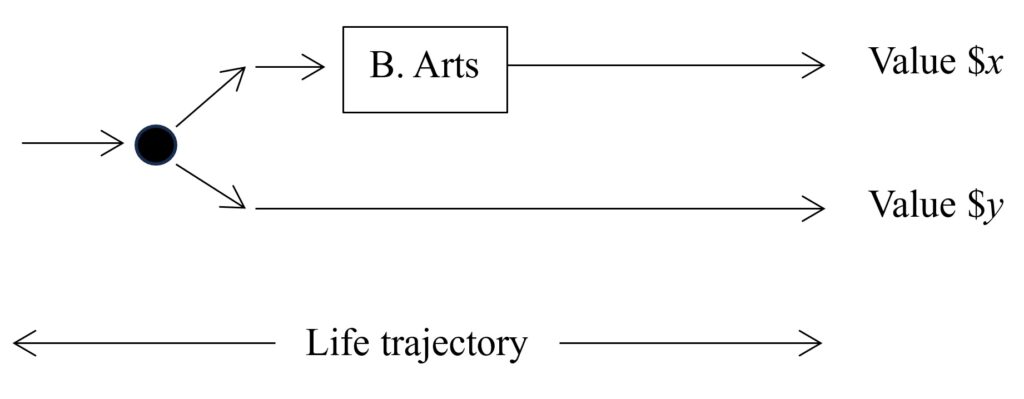

Consequently, we need a methodology that relaxes both assumptions. Figure 1 highlights the characteristics that such a methodology must have. The figure represents a person’s life trajectory, who arrives at a crossroad (the black dot in Figure 1), when they must decide to complete a Bachelor of Arts or pursue an alternative pathway.

If they opt to study a Bachelor of Arts, assume they will produce a bundle of value (for example, critical thinking skills) gaged at $x during their lifetime (still assume we manage to establish what is of value and how to measure it). The bundle contains value that is both attributable and non-attributable to completing the Bachelor of Arts.

If, at the same crossroad, the person chose to pursue an alternative pathway instead, assume they will produce a bundle of value gaged at $y during their lifetime. The bundle valued at $y contains value that is exclusively non-attributable to completing the Bachelor of Arts. The difference then between $x and $y is the value exclusively created by completing the Bachelor of Arts.

This methodology is resistant to the two assumptions discussed earlier. That is, comparing two alternative life trajectories for the same person differences out critical thinking skills the person may have developed when arriving at the crossroad and since this methodology explicitly accounts for the alternative life trajectory, it also addresses the second assumption regarding attributability.

However, we can only observe one of the two trajectories (the person either chose to study the Bachelor of Arts or they did not), rendering application of this approach in its strictest sense impossible. This is known as the ‘problem of the counterfactual’.

Figure 1. Life trajectory

Researchers have developed applicable methodologies, which approximate the above approach, which we will discuss briefly.

These methodologies rely on similar strategies: if the counterfactual is unobservable then we must compare observable pathways of at least two persons, one of whom completed a Bachelor of Arts and the other pursued the alternative life trajectory. Crucially, the determinants of the decision to complete the Bachelor of Arts should not be determinants of the outcome variable (critical thinking skills). To illustrate, Giri and Paily (2021) show that instructing scientific argumentation methods builds critical thinking skills in secondary school students. If students who were instructed in scientific argumentation methods at secondary school are also more likely to study a Bachelor of Arts, then the critical thinking skills that Bachelor of Arts graduates have are partially a result of completing the degree and partially a result of persons with high critical thinking skills self-selecting into a Bachelor of Arts.[3] We need a methodology that controls for the latter, which is successful if the decision to complete a Bachelor of Arts and the development of critical thinking skills are independent processes.

Beyond a random control trial (it would be hard to ethically justify withholding a group of students the right to study a Bachelor of Arts and do so for the three years duration of a Bachelor of Arts degree), there are two methodologies that satisfy the independence condition in different ways; natural experiments and quasi-experimental settings.

Where a random control trial is likely unfeasible, a situation may occur in which the conditions of a random control trial arise naturally such as a changed policy environment (that is, a natural experiment). Circumstances on either side of the policy change may cause persons in pre-policy change conditions to make a different choice than in the post-policy change environment. For example, take the changes to student contributions to tertiary studies in the society and culture discipline that were legislated in 2021.[4] Differences in life trajectories of pre-policy change students to similar students post-policy change, where the policy change causes students to no longer study a Bachelor of Arts, can be validly attributed to completing the degree. However, it will be difficult to identify groups of students who alter their study plans, challenging the applicability of this methodology.

Alternatively, researchers can rely on quasi-experimental settings, such as ‘difference-in-differences’, ‘regression discontinuity’, ‘instrumental variable’, and ‘matching-estimator’ designs. We focus on the latter as it is most suited to gaging the value of completing a Bachelor of Arts.

A matching-estimator setting consists of two stages. In stage one, the researcher predicts the likelihood of a person choosing to complete a Bachelor of Arts (regardless of whether the person chooses to complete the degree) based on the (shared) determinants of choosing to study a Bachelor of Arts and the development process of critical thinking skills. Then in stage two, the researcher compares critical thinking skills of two persons with similar a-priori likelihood of choosing to complete a Bachelor of Arts, however, one person did study the degree, whereas the other took the alternative pathway. The decision to choose to complete the degree and the development process of critical thinking skills are now conditionally independent, that is, they reason why the two compared persons chose different pathways is independent of the development of critical thinking skills.

The application of a matching-estimator design is data hungry. The set of shared determinants of choosing to complete a Bachelor of Arts and the development process of critical thinking skills may be large (and not necessarily observable), all of which need to be controlled for (or matched) to causally estimate the effect of completing a Bachelor of Arts on critical thinking skills.

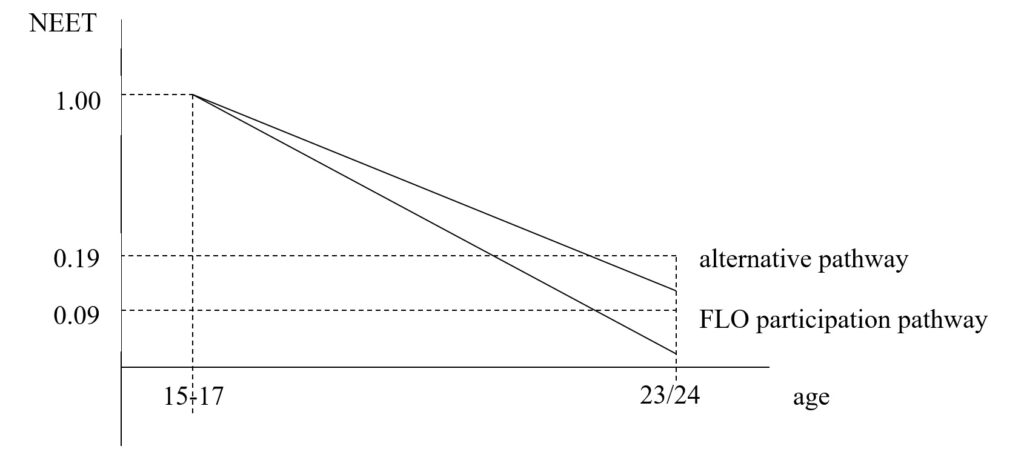

We are not aware of a study using a matching-estimator design to establish the value of HASS education. However, applications in the field of education exist. For example, Thomas (2019) applied a matching-estimator design to establish the value of flexible learning organisations (FLOs), which reengage students that disenfranchise from Australian mainstream schools. Thomas uses Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth data, which follows about 10,000 students from age 15 through to age 25 annually. The study identified a group of students who are not in employment, education or training (NEET) at age 15 to 17 (NEET 15-17) and a group of students who, in terms of characteristics relevant to disenfranchisement, resemble, but who are in employment, education or training at age 15 to 17 (Non-NEET 15-17). Thomas modelled the former group as students who have disenfranchised from mainstream school and have not benefited from FLO participation. He modelled the latter group as students who have disenfranchised from mainstream school (or at least had all the characteristics to disenfranchise) and benefited from FLO participation. The findings suggest that FLO participants fare better in terms of NEET status at age 23/24 (ten percent point difference) than the non-participants.

We depict this analysis in Figure 2, which shows the two pathways that this method takes explicitly into consideration: the actual and predicted alternative pathways. The effect attributable to FLO participation is the difference between the two pathways.

Figure 2. Value attribution to Flexible Learning Organisations

We assert that a similar approach may be applied to determining economic value of HASS education, measuring the differences between those in HASS and those not in HASS.

Spatial Heterogeneity

The Thomas study offers interesting parallels to the economic valuation in HASS studies because it can be readily applied to regional contexts with relative ease. Since the outcomes achieved in the actual and the alternative pathway may depend on the regional setting in which they occur, the value of a Bachelor of Arts is likely to be spatially heterogeneous—a feature that is rarely recognised in valuation exercises.

For example, King et al. (15) show that first-in-family students are more likely to study the disciplines of nursing, education, management and commerce, society and culture (including a Bachelor of Arts). Therefore, as Patfield suggest, the alternative pathway to studying a Bachelor of Arts is more likely to not include tertiary education for first-in-family students, of which there are (far) more in regional Australia (‘They don’t expect’). Consequently, the alternative pathway of a metropolitan student completing a Bachelor of Arts may look quite different from the alternative pathway of a regional Bachelor of Arts student.

Additionally, if the share of the workforce with university education is lower in the regions (which the first-in-family data suggest), then critical thinking skills are in relative strong demand in the regions, raising the value of completing a Bachelor of Arts degree accordingly (in terms of employment opportunities). That is, the value of the chosen pathway may be spatially dependent.

Both reasons justify a regional breakdown of a valuation exercise, rather than a one-size-fits-all estimate of the value of a Bachelor of Arts.

Researchers wishing to attribute value to a public service must (most likely) rely on a quasi-experimental setting. Such a strategy has several shortcomings, and we will focus on two: longitudinal data requirements and partial-equilibrium analysis.

Longitudinal Data Requirements

The researcher that wishes to gage the value of completing a Bachelor of Arts must follow the graduate throughout their life. Consequently, not only does the researcher need cross-sectional data (which covers a broad range of shared determinants), but also longitudinal data to sufficiently cover life trajectories, i.e., the researcher needs panel-data.

Since there are hardly any (if any) panel-data sets that cover complete life trajectories, researchers must revert to second-best solutions. They typically employ stepping-stone outcome variables. In our running example, we used critical thinking skills as an outcome variable. It is a variable that is measurable at degree completion. Researchers have linked critical thinking skills to improved labour market outcomes (for example: Deloitte; Doidge et al.; Parker et al.). Hence, we can use insights from these studies to apply the attributable increase in critical thinking skills as a result of completing a Bachelor of Arts as a stepping stone to map out value in the labour market of completing a Bachelor of Arts (for example, additional lifetime wages, income tax, and savings on unemployment benefit payments).

The shortcoming of this approach is that using stepping-stone (for example, critical thinking skills) rather than final-outcome variables (for example, labour market outcomes) introduces noise between the treatment variable (completion of a Bachelor of Arts) and outcome (for example, labour market outcomes). The lack of sufficiently long panel-data sets makes this shortcoming unavoidable.

Partial Equilibrium Analysis

Value attributed to a public service using random control trials, natural experiments, or quasi-experimental settings produce person-related value. For example, the person who completed the Bachelor of Arts (rather than the alternative pathway), gains additional critical thinking skills which led to higher lifetime wages, and higher income tax and savings on unemployment benefit payments. The first value falls to the person, the latter two to society, but all three are related to the person, who chose to complete the Bachelor of Arts rather than an alternative pathway.

However, a person completing the Bachelor of Arts degree may also produce value that supersedes person-related value. Some of this value may improve sense-making or enrich experience, which will lead to human flourishing (see, for example: Lomas; Tay et al.), but is hard to link to economic indicators and therefore left out of the analysis as argued earlier. Another part of the value that supersedes person-related value can be quantified, and this matters for regional graduates.

We give three examples, where regionality enhances value. First, think a firm that is making a locational choice. It will consider the availability of suitably qualified personnel in the region. A Bachelor of Arts program in the region, which provides a pool of workers with critical thinking skills, may persuade the firm to locate in the region, providing employment opportunities in the region (and not only to the Bachelor of Arts graduates). Agglomeration effects may induce other firms to locate nearby. Second, think a council government. The quality of decision making in council government depends upon, among other things, the critical thinking skills of its councillors and staff. A Bachelor of Arts program in the region provides a pool of workers with critical thinking skills, which—if employed in council—improves local public service provision of workers who have local knowledge and expertise. Third, think a public sector agency that fulfils an essential service in a region (that is, cannot leave). In absence of suitably qualified personnel (which the presence of HASS education in the region may provide), such an agency will face significant training costs and likely recruitment costs to deal with staff turnover.

The value created in the above three examples is not included in random control trials, natural experiments and/or quasi-experimental settings, because they focus on how the completion of the Bachelor of Arts benefits the graduate. In economics, this is called ‘partial-equilibrium analysis’, that is, the analysis focuses on a part of the economy (assuming no wider effects).

If benefits extend beyond the person (the presence of Bachelor of Arts graduates affects locational choice of firms, improves government decision making and reduces training/recruitment cost), the researcher must cast their net wider when assessing the value of a Bachelor of Arts program. Since these wider effects are likely to be region-specific, another source of spatial heterogeneity emerges, which necessitates a regional breakdown.

Conclusions

In an era dominated by economic metrics, the humanities and social sciences (HASS) sector must engage with economic valuation to demonstrate their value and secure funding. Despite resistance from HASS scholars, such valuation is crucial for influencing policy decisions and ensuring the sustainability of these disciplines. The concern is especially acute for regional areas.

Whilst some HASS scholars critique the underlying assumption of economic metrics that value can be quantified (for example: Belfiore; Olmos-Peñuela et al.) and others have developed models to articulate where HASS produces value (Lomas; Tay et al.), this article—acknowledging the above—focuses on the methods used in economic value attribution. Our exploration of methods to attribute economic value to HASS education highlights the complexity of this task. The proposed methodology, which compares life trajectories of graduates with alternative pathways, attempts to address the inherent challenges of attributing value to HASS education. Additionally, by recognising the spatial heterogeneity and regional differences in value creation, this approach provides a more nuanced understanding of the economic impact of HASS degrees to regional contexts.

The analysis underscores the importance of collecting detailed longitudinal data to capture the life trajectories of HASS graduates. While this data is currently limited, employing stepping-stone outcome variables like critical thinking skills can provide valuable insights into the broader economic impacts of HASS education.

Moreover, the partial-equilibrium analysis traditionally used in economic valuation may overlook broader societal benefits, particularly in regional contexts. HASS education contributes not only to individual graduates but also to regional development, public service quality, and local economies. Recognising these wider effects emphasises the necessity of a regional breakdown in valuation exercises to capture the full spectrum of benefits provided by HASS education.

While economic valuation of HASS education presents significant challenges, it is crucial for demonstrating the sector’s value in the fiscally constrained environments of the foreseeable future. By adopting robust methodologies and embracing economic analysis, HASS scholars can better advocate for their disciplines, ensuring their continued relevance and support. This proactive engagement will not only benefit individual students and scholars but also enhance the regional communities in which they live and contribute to the broader societal good.

Riccardo Welters is an Associate Professor in Economics at James Cook University. With a background in labour market economics, his research focuses on the effects of financial hardship on labour market outcomes of unemployed workers. A research domain, in which the establishment of cause and effect (that is, value attribution) is difficult.

Jonathan Kuttainen is a multidisciplinary researcher and project manager with a PhD in Sociology, specialising in the social and economic impacts of digital innovations and regional community development. His doctoral research examined the transformative effects of digital financial services in rural Uganda, drawing on interdisciplinary perspectives from sociology, economics, and anthropology. Currently, he is leading initiatives for the Great Barrier Reef Aquarium’s major refurbishment, including co-designing exhibits with Traditional Owners and fostering partnerships for its STEM education centre. His research and professional interests focus on bridging disciplines to address socio-economic challenges, with an emphasis on community development and applied research that delivers tangible benefits for regional communities.

Notes

[1] There is significant diversity in the types of HASS scholarship being drawn on in this essay. For simplicity references to HASS and humanities are used interchangeably while recognising the vast scope of differences that exist between the disciplines and their national contexts.

[2] For ease of argument, we assume that every student that starts a Bachelor of Arts degree will complete it. That is of course not true, with ramifications for the valuation exercise. However, these ramifications are not the focus of this essay, but certainly worthwhile further research.

[3] Anecdotally, students entering HASS education are less likely to have had exposure to natural sciences at secondary school but are considered to have better critical thinking skills, suggesting other selection processes into HASS education exist, which may further entangle determinants of degree choice and outcome variables.

[4] Refer to the changes made to student contributions at <http://www.education.gov.au/job-ready>.

Works Cited

AHRC—Arts and Humanities Research Council. Leading the World. The Economic Impact of UK Arts and Humanities Research. 2009.

Archambault, Éric, and Vincent Larivière. ‘The Limits of Bibliometrics for the Analysis of the Social Sciences and Humanities Literature.’ World Social Science Report 2009/2010. 2010. 251-4.

DESE—Department of Education, Skills and Employment. Job-ready Graduates Package Submission to the Standing Committee on Education and Employment. 2020.

Bate, Jonathan. ‘Introduction.’ The Public Value of the Humanities. Ed. Jonathan Bate. Bloomsbury, 2011. 1-13.

Belfiore, Eleonora, and Oliver Bennett. The Social impact of the Arts: An Intellectual History. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Belfiore, Eleonora. ‘“Impact,” “Value” and “Bad Economics”: Making Sense of the Problem of Value in the Arts and Humanities.’ Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 14.1 (2015): 95-110.

Benneworth, Paul. ‘Putting Impact into Context: The Janus face of the Public Value of Arts and Humanities Research.’ Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 14.1 (2015): 3-8.

Bulaitis, Zoe. ‘Measuring Impact in the Humanities: Learning from Accountability and Economics in a Contemporary History of Cultural Value.’ Palgrave Communications 3.1 (2017): 1-11.

Chiang, Kuang-Hsu. ‘From RAE to REF: Trust and Atmosphere in UK Higher Education Reform.’ Journal of Education and Social Policy 6.1 (2019): 29-38.

Chubb, Jennifer, and Mark Reed. ‘Epistemic Responsibility as an Edifying Force in Academic Research: Investigating the Moral Challenges and Opportunities of an Impact Agenda in the UK and Australia.’ Palgrave Communications 3.1 (2017): 1-5.

Deloitte Access Economics. The Value of the Humanities: A Critical Foundation of Our Society. <http://www.deloitte.com/au/en/services/economics/perspectives/value-humanities.html>.

Giri, Vetti, and M. U. Paily. ‘Effect of Scientific Argumentation on the Development of Critical Thinking.’ Science & Education 29.3 (2020): 673-90.

Hazelkorn, Ellen, Mairtin Ryan, Andrew Gibson and Elaine Ward. Recognising the Value of the Arts and Humanities in a Time of Austerity. Centre for Social and Educational Research, Dublin Institute of Technology. July 2013.

Holbrook, J. Britt. ‘The Future of the Impact Agenda Depends on the Revaluation of Academic Freedom.’ Palgrave Communications 3.1 (2017): 1-9.

King, Sharron, Ann Luzeckyj, Ben McCann and Charmaine Graham. Exploring the Experience of Being First in Family at University: A 2014 Student Equity in Higher Education Research Grants Project. Curtin University of Technology, 2015.

Kuttainen, Victoria. ‘The Promise and Betrayal of Arts and Culture in Regional Australia.’ Overland 13 February 2023. <http://www.overland.org.au/2023/02/the-promise-and-betrayal-of-arts-and-culture-in-regional-australia>.

Levitt, Ruth, Claire Celia, Stephanie Diepeveen, Siobhán Ní Chonaill, Lila Rabinovich and Jan Tiessen. Assessing the Impact of Arts and Humanities Research at the University of Cambridge. Technical Report. RAND Corporation, 2010. <https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR816.html>.

Lomas, Tim. ‘Positive Art: Artistic Expression and Appreciation as an Exemplary Vehicle for Flourishing.’ Review of General Psychology 20.2 (2016): 171-82.

Marginson, Simon. ‘Academic Creativity under New Public Management: Foundations for an Investigation.’ Educational Theory 58.3 (2008): 269-87.

Martin, Ben R. ‘The Research Excellence Framework and the “Impact Agenda”: Are We Creating a Frankenstein Monster?’ Research Evaluation 20.3 (2011): 247-54.

McCormack, Silvia, and Paula Baron. ‘The Impact of Employability on Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Degrees in Australia.’ Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 22.2 (2023) 164-82.

Olmos-Peñuela, Julia, Paul Benneworth and Elena Castro-Martínez. ‘Are Sciences Essential and Humanities Elective? Disentangling Competing Claims for Humanities Research Public Value.’ Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 14.1 (2015): 61-78.

Parker, Stephen, Andrew Dempster, and Mark Warburton. Reimagining Tertiary Education: From Binary System to Ecosystem. Melbourne: KPMG, 2018. <https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2018/reimagining-tertiary-education.pdf>.

Patfield, Sally. ‘They Don’t Expect a Lot of Me, They Just Want Me to Go to Uni.’ The Conversation 16 December 2022. <https://theconversation.com/they-dont-expect-a-lot-of-me-they-just-want-me-to-go-to-uni-first-in-family-students-show-how-we-need-a-broader-definition-of-success-in-year-12-196284>.

Pike, Deborah. ‘The Humanities: What Future?’ Humanities 12.4 (2023): 85-112.

PWC—Price Waterhouse Coopers. Lifelong skills: Equipping Australians for the Future of Work. Deakin: Australian Technology Network of Universities, 2018. <https://www.pwc.com.au/education/lifelong-skills-aug18.pdf>.

Reale, Emanuela., Dragana Avramov, Kubra Canhial, Claire Donovan, Ramon Flecha, Poul Holm, Charles Larkin, Benedetto Lepori, Judith Mosoni-Fried, Esther Oliver, Emilia Primeri, Lidia Puigvert, Andrea Scharnhorst, Andràs Schubert, Marta Soler, Sàndor Soòs, Teresa Sordé, Charles Travis and René Van Horik. ‘A Review of Literature on Evaluating the Scientific, Social and Political Impact of Social Sciences and Humanities Research.’ Research Evaluation 27.4 (2018): 298-308.

Small, Helen. The Value of the Humanities. Oxford UP, 2013.

Smith, Richard. ‘Educational Research: The Importance of the Humanities.’ Educational Theory 65.6 (2015): 739-54.

Tay, Louis, James O. Pawelski, and Melissa G. Keith. ‘The Role of the Arts and Humanities in Human Flourishing: A Conceptual Model.’ The Journal of Positive Psychology 13.3 (2018): 215-25.

Thomas, Joseph. Neoliberal Performance and Resistance in Australia’s Flexible Learning Sector. 2019. James Cook University, PhD dissertation.

Turner, Graeme, and Kylie Brass. Mapping the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences in Australia. Australian Academy of the Humanities, 2014.