by Paul Allatson

© all rights reserved

In mid-December 2003, barely a few days after the capture of Saddam Hussein by U.S. forces on December13, I received in my email inbox a jpeg that features the former Iraqi dictator sitting in a chair, a silver apron covering his body, while around him stand or kneel the various members of the popular U.S. reality TV show Queer Eye for the Straight Guy [see figure 1].

Figure 1: Jpeg circulated Dec. 2003 (JD).

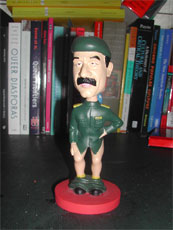

Some months later, I acquired what U.S. collectors like to call a bobblehead or nodder, a small doll made of a synthetic polymer resin with moveable head, in this instance a uniformed Saddam Hussein with his trousers down around his ankles, and a large missile painted in the colours of the U.S. flag embedded in his exposed buttocks [see figures 2, 3 and 4].

Figure 2: Saddam Hussein bobblehead (Photograph by Maja Mikula).

This essay, a meditative show-and-tell make-over of sorts, springboards from the conjunction of these two queerly touched products of global pop-culture, both of which also function as imperial-history military memorabilia. That conjunction suggests that the recent coming out of the queer “I” in Queer Eye could never simply be a televisual fairies’ tale. Rather, I want to suggest that the show–which has been aired, and in some cases franchised, in numerous countries since 20032–metonymizes the consolidation of the Bush Jr-led United States of Empire (henceforth, the U.S.E.), itself undergoing a formidable combat-fatigue chic make over since 9/11, 2001. With the world on its receiving end, Queer Eye ably represents the U.S.E.’s current economic and political stature, loved and loathed on a global level. The intimate relationship between The War on Terror and The ( Queer Eye ) War on Terrible Taste that I explore in this paper is neither coincidental nor far-fetched. Rather, that relationship is betrayed in the very coincidence of disparate pop-cultural texts and objects, which implicate a dominant and dominating queer purview in the operations of the state from which that purview emanates. Tentatively calling this purview imperial queer, my paper draws attention to the capacity of U.S.E. queer, and its representatives, to do two things. First, to enact colonising and commodifying identity pressures. And second, to do so by replicating the identity-making protocols, national dreamscapes, and disciplinarian ambitions of the geopolitical state that dominates the global order in our early 21 st century epoch.

The perversion of liberation

Since the current global order is often described as late capitalism, it seems fitting to proceed by relating the televisual coming-out of the queer “I” to questions of class and liberation. In 1972, the French philosopher Guy Hocquenghem drew on Marcuse to provide a salient reminder of the links between class and homosexuality:

If our society really is experiencing what Marcuse believes is a growing homosexualisation, then that is because it is becoming perverted, because liberation is immediately de-territorialised. The emergence of unformulated desire is too destructive to be allowed to become more than a fleeting phenomenon which is immediately surrendered to a recuperative interpretation (1993: 94).

Hocquenghem argues that in the capitalist system’s drive to disarm the threat posed by homosexual desire, or as he puts it, “unformulated desire”:

Capitalism turns its homosexuals into failed ‘normal people,’ just as it turns its working class into an imitation of the middle class. This imitation middle class provides the best illustration of bourgeois values (the proletarian family); failed ‘normal people’ emphasise the normality whose values they assume (fidelity, love, psychology, etc.). (1993: 94)

Queer Eye at once confirms these prescient observations and amends them. The queer in the show is drafted into the service of the capitalist order. This means that, the multiplication of “I”s notwithstanding, the queer in Queer Eye amounts to a libidinal irrelevance, of no actual account beyond TV-network ledger columns and a tally of heterosexuals whose unions are redeemed by the queer touch of the Fab Five. The capitalism that underwrites this transitory spectacle, and whose products get regular walk-on roles and multiple ovations, thus equips its failed normal people with the means by which to turn working class men (and their female partners) into an imitation of the consumerist middle class represented, in this instance, by the failed normal people themselves.

This process of imitation and domestication can be put another way, as does David Collins, one of U.S.E. Queer Eye ‘s executive producers:

The concept was basically five gay professionals in fashion, grooming, interior design, culture, food and wine coming together as a team to help the straight men of the world find the job, get the look, get the girl (italics mine; Idato 2003: 4).

The official Queer Eye website, hosted by Bravo cable TV network (bravotv.com), expands on this brief:

They call themselves the Fab Five. They are: An interior designer, a fashion stylist, a chef, a beauty guru and someone we like to call the ‘concierge of cool’–who is responsible for all things hip, including music and pop culture. All five are talented, they’re gay and they’re determined to clue in the cluttered, clumsy straight men of the world. With help from family and friends, the Fab Five treat each new guy as a head-to-toe project. Soon, the straight man is educated on everything from hair products to Prada and Feng Shui to foreign films. At the end of every fashion-packed, fun-filled lifestyle makeover, a freshly scrubbed, newly enlightened guy emerges–complete with that ‘new man’ smell!

‘Queer Eye for the Straight Guy’ is a one-hour guide to ‘building a better straight man’–a ‘make better’ series designed for guys who want to get the girl, the job or just the look. With the expertise and support of ‘The Fab 5’–Ted Allen, Kyan Douglas, Thom Filicia, Carson Kressley and Jai Rodriguez–the makeover unfolds with a playful deconstruction of the subject’s current lifestyle and continues on as a savagely funny showcase for the hottest styles and trends in fashion, home design, grooming, food and wine, and culture. The show was recently awarded the 2004 Emmy Award for Outstanding Reality Program.

In keeping with this “playfully deconstructive” mission, the Fab Five fulfil their weekly brief to transform the straight man away from gaucherie, the unemployment queue or “on-welfare” appearance, and, even more tellingly, the ever-present danger of hetero-relationship failure. Each episode ends with the Fab Five sipping champagne in a spacious loft apartment beyond the financial means of most viewers. Nicely ensconced, they assess the success of their day’s work, before providing a run-down on the products whose future sales provide the show’s raison d’être. Every week the outcome is the same: remade, the straight man will keep his woman, or be in a position to attract one. Each week, the failed normal men primp and pimp for the “political regime” of heterosexuality, to use Monique Wittig’s definition (1992: xiii).

It is worth noting, moreover, that Queer Eye has two more specific, yet easily overlooked, roles to play in heterosexuality’s upkeep under late capitalism. First, by returning the improved straight men to their women, and asserting that the health of these relationships now rests on an untrammelled consumerism, the show participates in what Adrienne Rich calls “the enforcement of heterosexuality for women as a means of assuring male right of physical, economic, and emotional access” (1993: 238). Second, Queer Eye ‘s masculinist and heteronormative parameters exclude the lesbian, rendering her an epistemological irrelevance in the show’s purportedly queer habitus, a discounting that Rich argues is also a key tactic in the perpetuation of compulsory heterosexuality (1993: 238).

It is arguable that the absence of the lesbian from the queer purview at work Queer Eye is not surprising, given the long historical association between bourgeois consumption and gay male cultural typologies in the west, and the concomitant exclusion of lesbians from those typologies. As numerous critics have noted, the western lesbian has neither enjoyed the socieconomic status, nor the social visibility and subjective meaningfulness, that would enable lesbian consumption on a par with that of gay men (Clark 1993: 187). At the same time, Queer Eye ‘s governing protocols of overt consumption are again unsurprising, in that they announce a self-conscious and knowing positioning of the show’s “queer” rationale in a long Western historical continuum that not only embraces a homosocial aesthetic of worldliness and refined taste, but regards that aesthetic as the essential identificatory hallmark of the bourgeois gay subject himself. Neither heterosexual men nor women could be the “natural” bearers of that aestheticized and commodifiable subjectivity, hence the need for homosexual-lead programs of aesthetic acculturation. At times, moreover, that aesthetic–and the class credentials that provided the preconditions for it–enabled some homosexual men to take full advantage of the mobilities and privileges afforded by imperialism and thus enjoy a measure of sexual license, and access to “native” subjects and other commodities, living and inanimate, that would have been impossible at home (Lane 1995; Aldrich 2003).

And yet there is another way of reading these continuities that does not simplistically or fixedly regard Queer Eye ‘s televisual function as the latest manifestation of a privileged Western gay-male consumerist tradition and/or aesthetic sensibility. The alternative reading would re-assess that tradition’s “aesthetic” parameters as intimately tied to, and politically curtailed by, the historical-material evolution of both capitalism and imperialism, and the heteronormative assumptions underwriting both systems in terms of their productions of subjects, values, and profits. That alternative reading would recognize that the globalization of (homo)sexuality, to paraphrase the title of Altman’s 2001 study, Global Sex, and the rise of sexuality-based political agendas, from gay and lesbian liberation to queer activism, are themselves intimately and ambivalently linked to the “discovery” and subsequent evolution of (homo)sexuality since the late nineteenth century as yet another sign of the productive power of western capitalist and imperialist drives.

Queer cooption and containment

The historical lines of tradition and systemic power noted above raise the important question of what the “queer” in Queer Eye signifies, in both subjective and political senses. With its emphasis on product placement and sales, and its weekly commitment to the superficial make-over of the heterosexual male in line with bourgeois U.S.E. gay male ideals of taste, Queer Eye appears to have no semantic affinity with the queer described by Michael Warner. For Warner, queer functions as “an aggressive impulse for generalization; it rejects a minoritizing logic of toleration or simple political interest-representation in favor of a more thorough resistance to regimes of the normal” (1993: xxxvi). That anti-normative resistance is crucial. As Murray Pratt and I have argued elsewhere (2005), a number of commentators assert that a queer critical approach is productive precisely because it contains the seeds of its own conceptual undecidability, if not dissolution, despite the critiques of identity manufacture and ascription driving that approach (Jagose 1996: 127-32). That is, in its most radical form, queer announces an ambivalently deconstructive critical project that to varying degrees oscillates between utopic faith in its identificatory promises, and acceptance of the inevitable impossibility of fulfilling such promises. Most hopefully put, this notion of queer amounts to a non-normative critical sensibility that is anchored in, and yet exceeds, the realms of sexual identity and desire. The “queer” in Queer Eye, however, does not share these queerly deconstructive ambitions to resist “regimes of the normal,” including those announced and embodied by “queerness” itself. But accepting that the “queer” of Queer Eye has nothing to do with radical queer enterprises, it would also seem that the show’s (homo)sexual ambit has nothing to do with pre-queer gay liberation either. As Dennis Altman argued in his influential Homosexual Oppression and Liberation, originally published in 1971, the gay liberation movement that emerged in the U.S.E. “is much more the child of the counterculture than it is of the older homophile organizations; it is as much the effect of changing mores as their cause” (1993: 164).

Neither queer nor gay liberational, but nonetheless purportedly homophilic, Queer Eye thus suggests that the once subversive promises and aspirations of sexual liberation projects, from the 1960s through to the new millennium, are being comically ignored in the U.S.E., and, indeed, wherever the U.S. model of buffed and accessorized male gayness exercises “from drab to fab” monopoly. The only promise of the Queer Eye show is afforded by an obsessive-compulsive brand-name shopping mania, a concomitant poverty of conversation, and a narcissistic concern with sanitized, homogenised, and blanched body surfaces and personalities. In this, the whitewash of the show’s sole non-Anglo, Jai Rodriguez, speaks volumes, as José Esteban Muñoz notes when drawing attention to the way Queer Eye “assigns queers of color the job of being inane culture mavens” (2005: 102).3

Again, Hocquenghem provides an explanation for this scenario of queer cooption and disarmament: “As long as homosexuality serves no purpose, it may at least be allowed to contribute that little non-utilitarian ‘something’ towards the upkeep of the artistic spirit” (1993: 108). The queer who subscribes or succumbs to this logic occupies a social space of libidinal and political impotence. The tokenistic and therefore safe “upkeeping of the artistic spirit” in Queer Eye threatens no orders. So tamed, the show’s queer purview becomes symptomatic of the slow but inexorable dismantling or discounting of the hard-earned rights and ethical decencies bequeathed by civil rights activists in what increasingly appears to be a distant golden era. Such programming marks the defeat of queer desire’s radical potential to reterritorialize capitalism’s structural ally, the heterosexual economy. Regarded this way, it is impossible to agree with critics who argue that the show homes in on the crisis at the very heart of heterosexuality itself (Torres 2005: 96), or that it may be viewed as a paradigmatic instance of the new metrosexuality, part of what Toby Miller describes as “a much wider phenomenon of self-styling and audience targeting” that at once reflects and exacerbates the body image woes of a North-American masculine constituency (2005: 115). Such readings gloss over the hapless fate of queer itself in the show. Herein lies Queer Eye ‘s unqueer rub. As Hocquenghem argues:

far from putting an end to the exclusive function of reproductive heterosexuality, the actual dissolution by capitalism has turned the family into the rule inhabiting every individual under free competition. This individual does not replace the family, he prolongs its farcical games. (1993: 93)

In Queer Eye ‘s particular traffic in “farcical games,” its enlisted queer individuals have no purpose but to playfully service the heterosexual unit and thus to safeguard the reproductive logics of capitalism.

Queer Wars

But, in this particular instance, the queer on view here has another purpose, which is nonetheless also related to the way that the queer is permitted “to contribute that little non-utilitarian ‘something’ towards the upkeep of the artistic spirit” in the post 9/11 historical-material moment. And here it is useful to return to the image that began circulating in cyberspace shortly after U.S.E. forces had captured Iraq’s former leader Saddam Hussein. I accept that neither the Fab Five in question, nor the producers of the show, endorsed or were probably responsible for the montage and its virtual circulations. But the image is telling for what it says about the cooptability of the non-queer-queerness popularized and perpetuated by Queer Eye. The intended humour of the image rests as much on the apparently unexpected conjunction of the former Iraqi dictator and a televisualised notion of U.S.E. queer, as it does on the ways by which the threat purportedly posed by Saddam to U.S.E. interests can be contained and disarmed by the queers and their cheerfully compliant make-over skills. Obviously, this is a complex image, and many readings can be drawn from it. But I cannot look at this montage without thinking of those now iconic photographs of U.S.E. soldiers mistreating Iraqi prisoners of war, which began to dominate news coverage of the war in the early months of 2004.

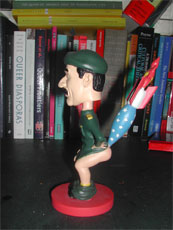

Figure 3: Saddam Hussein bobblehead (Photograph by Maja Mikula).

If queerness in this Jpeg is, at the very least, enlisted to do to Saddam what the U.S.E. military machine is attempting to do to Iraq itself, that is make the country over in a more U.S.E.- friendly and unthreatening pattern, a notion of queerness also seems to be at work in the bobblehead souvenir of the U.S.E.-led invasion of Iraq. The person from whom I purchased the Saddam bobblehead on eBay advertised the item with the following blurb:

Looks like someone got caught with his pants down! Not only that, but a Star Spangled Bomb found its way to the GPS coordinates of ‘you know where.’ The Saddam Hussein Bobble Head is made of ceramic polyresin and stands about 6 inches tall. The former dictator is going to have a hard time sitting down for a while. Perfect gift for your family member or friend currently serving the US Armed Forces. We ship to APO/FPO addresses at NO EXTRA CHARGE!

The irony that inheres to this “Perfect gift for your family member or friend currently serving the US Armed Forces,” stems from the fact that Saddam is figuratively and connotatively sodomized by the U.S.E., despite the anatomically impossible angle of the embedded missile.

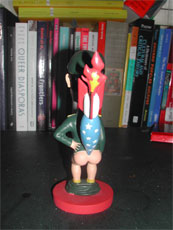

Figure 4: Saddam Hussein bobblehead (Photograph by Maja Mikula).

The logics behind this bobblehead are, in part, determined by an active-passive matrix, by which the threat signified and embodied by Saddam is emasculated and feminized through male penetration. The sodomite Saddam is at once rendered passive and pacified, his destructive aura queered, disarmed and (one assumes) thereby dispensed with. Yet, the neatly alliterative equation of Saddam and sodomy evident in this statuette is not a new phenomenon. As Jonathan Goldberg notes, that link was being made in the lead up to the first Gulf War with t-shirts emblazoned with such phrases as “America Will not Be Saddamized” and “Hey Saddam This Scud’s For You,” the scud aiming for the target of Saddam’s buttocks. In his book Sodometries (1992), Goldberg in fact prefaces his discussion on renaissance textual representations and discourses of sodomy by examining some of the Saddam-based image-texts from the Gulf War. He rightly notes that the rhetoric at work in such image-texts is far from straightforward, even as their governing rhetoric confirms that “the productive value of sodomy… today should not be underestimated” (1992: 6).

In the Gulf War image-texts, then, are evident “not only the complex overdeterminations of the present moment–confluences and conflicts within and between popular culture, the media, late-capitalist commodification, the military, the government–but also certain strange historic overlaps” (1992: 3). Goldberg argues that there is an incoherence to the Gulf War images that is explicable in terms of Foucault’s notion of sodomy as an “utterly confused” category: pre-modern and modern “regimes of sexuality” are at complicated work whenever the figure of the sodomite is invoked in our era, as in the bobblehead memento of the current Iraq war. As a result, Goldberg notes, the queerness that coheres to Saddam can variously signify bestiality, an inversion of a natural gendered order, feminization, a sexual molestation, confirmation of an Orientalist-derived discourse that locates the origins of sodomy in the Mediterranean and in Islamic cultures, a modern sexual identity, and a sexual-behaviour pattern (which in itself is not a synonym for homosexuality) that invites detection and punishment. To this list can be added paedophilia, as exemplified by the western media’s responses to Saddam Hussein’s television appearances with 7 year-old Stuart Lockwood, one of a number of Westerners deployed by the Iraqi president as “human shields” in the lead up to the first Gulf war in 1991 (Foss 1991).4 At the same time, the multivalent and unstable queernesses accruing to Saddam Hussein cannot signify in these multivalent ways without a willing penetrating agent, in which case the U.S.E. and its armed representatives are also potentially implicated in some, if not all, of the discursive and historical confusion that Goldberg, following Foucault, reads into such U.S.E. representations of Saddam Hussein. The U.S.E. can only figuratively sodomize Saddam by being, in some way, more powerfully queer.

One question that Goldberg poses after his discussion of Saddam as sodomite, and of the concomitant discursive slippage from that category to the equally confused category of homosexuality, seems particularly prescient here. He asks, “What place is sodomy assumed to have in the mind of the ‘America’ being addressed?” (1992: 5). That question may be reworded in light of the international popularity and reach of Queer Eye for a Straight Guy : “What place is queer assumed to have in the mind of the ‘America’ being addressed?” It is no coincidence that the Queer Eye show emanates from the U.S.E., a country with its own powerful discourses of individual self-fashioning unconstrained by institutional limits and material history, and of “America” as an exceptional national bastion of capitalist enterprise. The superficial work done by the Fab Five is also meaningful in terms of these individualised national and economic narratives as the group labours to sell the myth of, and grant access to, an individuated American Dreamscape. Since the Fab Five are the agents by which entry to the Dream is managed, they provide a differently dressed parallel to those other representatives of the U.S.E. who are routinely authorised to uphold their state’s role as the self-anointed worldwide nemesis of so-called rogue regimes. Indeed, when the most extrovert of the Fab 5, Carson Kressley, scrawls “Bad Taste Kills” on the door of one rogue target, that action makes it difficult to avoid making the analogy between the War on Terror and the War on Terrible Taste, as the author of the Saddam/ Queer Eye Jpeg perhaps unwittingly also realized. Both wars are conducted as just and righteous enterprises. Both require a Dreamscape reasoning that can only recognise (U.S.) good/taste and (non-, un-, anti-American) evil/tastelessness. And both wars are predicated on, and judged in terms of, the market share and returns that the fighting forces (U.S.E. Ltd; Queer Eye Ltd) win over any competition. It is rather telling that the official website of the U.S. Department of Defense welcomes web-browsers with the proud claim:

Welcome to the Department of Defense!

We are America’s…

- Oldest company

- Largest company

- Busiest company

- Most successful company

With our military units tracing their roots to pre-Revolutionary times, you might say that we are America’s oldest company.

And if you look at us in business terms, many would say we are not only America’s largest company, but its busiest and most successful.

So occluding its true function, the U.S.E. neatly rebrands its military industrial complex as a business. And business and success, it should be noted, are key aspirational terms in and for the ostensibly non-violent Queer Eye enterprise as well.

Queer and the United States of Empire

Such historical-material and national resonances appear to trouble Michael Warner’s claim that queer culture “is not autochthonous,” given that it has “no locale from which to wander” (1993: xvii).5 A popular gay bar in Sydney has the name Stonewall, a sign at the very least of the trans-Pacific influence of U.S.E.-derived queer histories in and on non-U.S.E. spaces and peoples. Clearly, some forms of queer can, and do, have U.S.E. locales from which to wander. To borrow from Hardt and Negri, the problem posed by that global nomadism lies in the extent to which some notions of queer are not only calibrated for empire, but align themselves with, and/or benefit from, it. In their discussion of the new postmodern and post-national age of Empire, Hardt and Negri make a semantic distinction between imperial and imperialist. They suggest that the U.S.E.’s suitability for empire is not imperialist, because it does not “spread its power linearly in closed spaces and invade, destroy, and subsume subject countries within its sovereignty” (2001: 182). Rather the U.S.E.’s global dominance in the current epoch rests on the imperial qualities contained in its constitution. That document, Hardt and Negri argue, serves as a discursive blueprint for the U.S.E.’s current worldwide status; it is “the model of rearticulating an open space and reinventing incessantly diverse and singular relations in networks across an unbounded terrain” (2001: 182). This assertion, of course, was penned before 9/11, 2001, and the subsequent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. But even without 9/11, the distinction between imperial and imperialist may not be as clear-cut, or as sensical, as Hardt and Negri claim.

To make this statement is not to perpetuate a notion of imperial/ism as a monolithic species of hegemony that is imposed on passive peripheries, and that is not and cannot be constantly resisted, its messages refashioned on local terrains with transformative implications for imperial and colonized locales alike. Rather, the globally circulating cultural phenomenon of the Queer Eye franchise suggests the need for alertness to the imperial/ist logics that may underwrite the claims made for and on behalf of queer, particularly when articulated in and from a base inside U.S.E. borders. Speaking of the tactics deployed in the 1990s by the U.S. activist group Queer Nation, for example, Lauren Berlant and Elizabeth Freeman note that the group’s operations never quite escaped from “the fantasies of glamour and of homogeneity that characterise American nationalism itself” (1997: 215). Queer Nation’s attempted queer resemanticisation of public spaces such as shopping malls, and its adoption of a faux corporate identity replete with logos and mission statements, indicate how avowedly radical or counter-national queer projects in the U.S.E. are nonetheless “bound to the genericizing logic of American citizenship, and to the horizon of an official formalism–one that equates sexual object-choice with individual self-identity” (1997: 215). Similar claims can be made of Queer Eye, even as the show sharply diverges from the queerly political agenda of Queer Nation in its resolute commitment to upholding the protocols of compulsory heterosexuality.

The highly popular Queer Eye package, and its make-over promise of straight male re-invention, has been sold to countries across the globe. Those countries include Australia where a local production went to air for the first time in February 2005. Interestingly, the Australian version, which replicated exactly the U.S.E. format, was not popular with Australian viewers and was plugged after airing for a few weeks. That failure, however, is not evidence that Australian audiences rejected the Queer Eye concept. Rather, it may simply indicate the paradoxical extent to which a local queer habitus has little (client state) capacity to resist the mass-mediating power of the U.S.E. queer paradigm. In Finland, too, the local remake of the Queer Eye franchise was not popular with viewers, but for different reasons; audiences complained that the show was even more overt than the U.S.E. original in its product placements and hard-sell marketing ethos. The paradox of both local reactions lies in the fact that U.S. Queer Eye survives, unscathed and untroubled, by the failure of its franchised progeny, arguably because its own televisual power rests on its internalized enlistment and pimp-like domestication of “queer” in the service of the heterosexual economy, global capitalism, and the United States of Empire itself.

Paul Allatson is Senior Lecturer in Spanish and (U.S.) Latino/a Studies at the Institute for International Studies, University of Technology, Sydney. His current research focuses on Latino/a cultural politics and citizenship, the mass-mediation of latinidades, and transcultural sexualities. Paul is the author of Latino Dreams: Transcultural Traffic and the U.S. National Imaginary (Rodopi, 2002) and the forthcoming Key Terms in Latino/a Cultural and Literary Studies (Blackwell, 2006).

FOOTNOTES

1. A shorter and earlier version of this paper was published as ” Queer Eye ‘s Primping and Pimping for Empire et al ” in Feminist Media Studies vol. 4., no. 2 (Summer 2004): 210-213. My thanks to the editors of that journal for permission to republish sections of that paper in modified form here. I would also like to thank the organizers and participants in the Sexual Revolutions Symposium, held at the University of Wollongong in December 2004, for their productive feedback and suggestions, and Elizabeth McMahon for her astute editorial comments and patience.

2. Those countries include Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, Malaysia, the Philippines, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, the U.K., Venezuela, and dozens more. Local versions of the Queer Eye franchise have appeared, with varying degrees of audience support, in such countries as Australia, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Spain (Operación G), and the U.K. In the U.S.A. Queer Eye debuted on the Cable network Bravo on July 15, 2003.

3. In a different vein, the British architect of the Anti-Gay movement (1996), Mark Simpson argues that even the traditional “gay-male” aesthetic of good taste propounded by Queer Eye is both anachronistic and so-class blind as to ignore the fact that most gay men in Britain, at least, are too happily working class to be “culture mavens” (2003).

4. My thanks to Jonathan Bollen for drawing my attention to this article.

5. Indeed, the claim is at odds with the positions taken by many of the contributors to Queer Diasporas (Sánchez-Eppler and Patton 2000), Queer Globalization (Cruz-Malavé and Manalansan IV 2002), Queer Frontiers (Boone et al. 2000), and Passing Lines (Epps and González 2005).

WORKS CITED

Aldrich. Robert. 2003. Colonialism and Homosexuality. London and New York: Routledge.

Allatson, Paul, and Murray Pratt. 2005. “Queer Agencies and Social Change in International Perspectives.” Position paper for the Annual Symposium and Workshop on Queer Agencies and Social Change, Institute for International Studies, UTS, December.

Altman, Dennis. 1993 (1971). Homosexual Oppression and Liberation. London: Serpent’s Tail.

Altman, Dennis. 2001. Global S ex. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berlant, Lauren, and Elizabeth Freeman. 1993. “Queer Nationality.” In Michael Warner (ed.) Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory, pp. 193-229. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Boone, Joseph A. et al., eds. 2000. Queer Frontiers: Millennial Geographies, Genders and Generations. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Clark, Danae. 1993. “Commodity Lesbianism.” In Henry Abelove, Michèle Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin (eds.) The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, pp. 186-201. New York and London: Routledge.

Cruz-Malavé, Arnaldo, and Martin F. Manalansan IV, eds. 2002. Queer Globalizations: Citizenship and the Afterlife of Colonialism. New York and London: New York University Press.

Epps, Brad, Keja Valens, and Bill Johnson González, eds. 2005. Passing Lines: Sexuality and Immigration. Cambridge, MA, and London. David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Press.

Foss, Paul. 1991. “The Children’s Crusade.” Art and Text vol. 38 (Jan.): 22-26.

Goldberg, Jonathan. 1992. Sodometries: Renaissance Texts, Modern Sexualities, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2001. Empire. Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press.

Hocquenghem, Guy. 1993 (1972). Homosexual Desire. Daniella Dangoor (trans.). Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Idato, Michael. 2003. “Pride or Prejudice?” Sydney Morning Herald [Australia]. September 29-October 5: TV Guide 4-5.

Jagose, Annamarie. 1996. Queer Theory. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Lane, Christopher. 1995. The Ruling Passion: British Colonial Allegory and the Paradox of Homosexual Desire. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press.

Muñoz, José Esteban. 2005. “Queer Minstrels for the Straight Eye: Race as Surplus in Gay TV.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies vol. 11, no. 1: 101-2.

Patton, Cindy, and Benigno Sánchez-Eppler, eds. 2000. Queer Diasporas. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press.

Queer Eye for the Straight Guy Official Website. Bravo Cable TV Network.

Accessed at:

http://www.bravotv.com/Queer_Eye_for_the_Straight_Guy/About_Us/

Rich, Adrienne. 1993. “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.” In Henry Abelove, Michèle Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin (eds.) The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, pp. 227-254. New York and London: Routledge.

Simpson, Mark. 1996. “Preface.” In Mark Simpson (ed.) Anti-Gay, pp. xi-xix. London: Freedom Editions.

Simpson, Mark. 2003. “Queen’s Evidence.” The Guardian (Nov.

1). Accessed at:

http://www.marksimpson.com/pages/journalism/queens_evidence.html

Torres, Sasha. 2005. “Why Can’t Johnny Shave?” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies vol. 11, no. 1: 95-97.

U.S. Department of Defense. 2002. “Dod 1: An Introductory Overview of

the Department of Defense.” Accessed at:

http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/dod101/dod101_for_2002.html

Warner, Michael. 1993. “Introduction.” In Michael Warner (ed.) Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory, pp. vii-xxxi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Warner, Michael. 1999. The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wittig, Monique. 1992. The Straight Mind and Other Essays. Boston: Beacon Press.