by Gail Feigenbaum

© all rights reserved

Of the various ways to approach the cactus garden at the Getty, let us choose a fantasy route that offers a perfect sense of orientation, but requires a helicopter. The helicopter flies us over a hundred sprawling miles of the city of Los Angeles and up the spine of the city—the relentlessly busy 405 freeway. The copter then hovers above the affluent communities of Brentwood and Bel Air in the northern part of Los Angeles, where the built habitation tapers off to just a scattering of splendid homes in the green or gold (depending on the season) foothills of the Santa Monica Mountains and the Sepulveda pass. Finally the helicopter reaches the hundred plus acres of the Getty Center built high and isolated atop a hill some thousand feet above sea level. This flyover affords us the first glimpse of the cactus garden. The helicopter is a hypothetical, of course; real visitors to the Getty are not airborne but come in cars and buses, park at the bottom of the hill and take a very scenic tram ride to the top where they are met, on most days, by panoramic views and bright sunshine.

Our bird’s-eye view takes in the long axis of the Getty’s campus from the north point which begins in a helipad and ends at the southernmost point, where an answering bastion supports the cactus garden. A helipad was required by the city for fire and emergencies, and while, fortunately, it has never yet had to be used for that purpose, it did inspire our fantasy of a helicopter approach as orientation to a very complicated site. The south promontory, according to John Walsh, former Director of the J. Paul Getty Museum, is an utterly non-functioning architectural ornament. Even if the parapet makes the site seem more fortress-like (a frequent criticism of the architectural design), the earthwork pseudopod asserts itself with flair in the landscape. From the helicopter we see that the surrounding hills seem wild, or nearly so; in fact, most of the contours and surfaces of the hillside were drastically altered to construct the Getty Center. Over three thousand California oak trees and more than sixteen hundred other trees were planted on the side. Still, it is wild enough to support a picturesque herd of deer—whose favourite grazing site, ironically, turns out to be the far from wild lawn of the disused helipad. But the modernist Getty Center itself is paved almost in its entirety in white travertine, into which pockets and accents of greenery are tucked in to relieve the sixteen thousand tons of stone that came from the same quarry in Italy used to build the Colliseum. All but the Central Garden are the work of the landscape architecture firm, the Olin Partnership.It is an irony of the Getty site that, owing to security concerns, some of the most charming garden spots can be enjoyed only by staff members, such as the palm court and the shady green Italian garden beside the helipad. And, at the southernmost extreme of the site, nobody except the gardeners can enter the cactus garden.

Fig. 1: View of cactus garden, Getty Center, Los Angeles, 1999. [Tim Rue Photo]

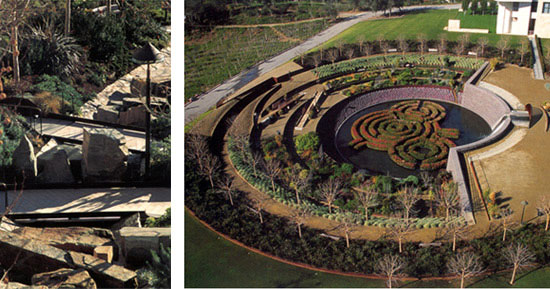

Although we are now off the helicopter, our arrival at the cactus garden continues to be deferred, by which means we replicate the experience of the visitor, for the cactus garden is at the most remote reach of the site. It is neither the most famous nor predominant garden at the Getty Center, and it is not the one most visitors know or even venture so far to encounter. By contrast, the Central Garden is rather famous and aptly named for it is indeed in the centre of things and hard to miss. Its zigzag path crossing and recrossing a stream invites the visitor down the slope, re-establishing what was once a natural ravine between the museum and the research institute. Down the ravine runs a watercourse which is interrupted by boulders from the Sierra foothills placed to create changing sound effects as the stream descends. It ends in a bowl where the water cascades over a stepped stone wall into a reflecting pool enclosing a maze of azaleas. The substantial and complex hardscape of the Central Garden is set off on both flanks by an even carpet of green lawn. Southern California artist Robert Irwin who created the Central Garden conceived it as a work of art—it is curated rather than tended and even has an accession number. Irwin himself called it ‘a sculpture in the form of a garden aspiring to be art.’ Each month Irwin walks the garden with the horticultural staff and he remains involved in selecting the plants which change dramatically with the seasons. The Central Garden is especially showy in springtime with the azalea maze in full bloom and bougainvillea flowering heavily over the trellises. It is very much a garden to stroll through, and a welcoming place for kids to run around in. With its formal intricacies, sculptural idiosyncrasies, and injections of bright colour, Irwin’s garden represented an audacious aesthetic breach with the austere, minimalist vision of Richard Meier, the architect of the Getty Center, but that is a story for another occasion.

Fig 2: Two views of Robert Irwin’s Central Garden, Getty Center, Los Angeles, 2001

Reproduced from Lawrence Weschler, Robert Irwin Getty Garden ( Los Angeles : J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001) [Photo: Becky Cohen]

After having visited the Central Garden, a fortunate stroller might happen on my preferred approach to the cactus garden. This would be the path of a visitor to the museum who wanders through the galleries of eighteenth-century French paintings and decorative arts, and unsuspectingly goes out a side door to find herself outside on a gleaming marble terrace with a view of all of Los Angeles, the surrounding hills and ocean stretching to the horizon. It is a bit of a shock. At first the light is almost blinding; it takes some minutes for eyes to adjust from the controlled dimness in the museum’s galleries to the bleaching glare of the southern California sun bouncing off the crystalline structure of the travertine. An alternate, equally dramatic approach from outdoors takes the visitor along the axis of the fountain in the museum’s plaza where an exquisitely framed promise of a view beckons through a slot between two pavilions. Passing along a sheer travertine wall, the visitor finds the entrance to the upper terraces of the cactus garden. Whichever the route, the outdoor path from the plaza, or the dazzling abrupt exit from the galleries, the cactus garden comes as a discovery. It comes suddenly and as a surprise—even to a visitor who is looking for it, and even to someone familiar with it and expecting it.

Fig. 3: View of cactus garden, Getty Center, Los Angeles, 2005 [Photo: Patricia Kikuchi]

Arriving at the terrace, one descends a gently sloping stair set against a travertine wall, passing on the right, first, a rectangular bed, then a second, densely planted with cactus and other succulents. At the bottom of this low stair where the sheer travertine wall ends, is the big reward: the terrace affording an overlook. Here is the promontory pushing out from the body of the building where a sliced-off wall defines its shape of a sharply cut backwards letter ‘P.’ The lower terrace of the garden cannot be entered. One looks down over it, always in aerial view as it were, and sees it in its dramatic situation, a kind of exclamation mark to the vast sprawling panorama of Los Angeles.

As a setting for a cactus garden, the promontory might seem a curious, if ultimately fitting site. It was not surprising to learn that this fortress-like structure with its high retaining wall was initially conceived to support a plaza where visitors could enjoy the spectacular view of the Los Angeles basin that stretches to the mountains and sea. But the Getty’s nearest neighbours voiced strong objections to allowing people to get close enough to overlook their property. In response the Getty planted a screen of fast-growing eucalypts and, more importantly for the garden, prohibited all access to the south promontory. Restricted access would have been inevitable in any case, for the walls are far too low too afford fall protection, and like all large American institutions open to the public, the Getty keeps an eagle eye on risk management.

With the making of the garden so recent (late 1980s into the early 1990s), and with the principal people involved available to be interviewed, one might expect that it would be easy to reconstruct the history of the project, to get hard facts about the original ideas and how the plans evolved. Instead the endeavour turned out to be a lesson in the instability of historical reconstruction: evidently not enough time has elapsed for the process to coalesce into a coherent (if contested or ambiguous) narrative. The earliest site plan that could be located testifies that a decision had been made to plant Palo Verde trees, a local species with rather delicate foliage that would not block the view of the building and grow to about thirty feet. Trees were ordered and set out in twenty-four inch planting boxes encircling the promontory. An undated architectural rendering from Olin’s office indicates that an island of cactus was already envisioned. According to Steve Rountree, however, who oversaw the entire building project for the Getty, ‘the trees looked stupid.’ Everybody hated the trees. John Walsh, then director of the J. Paul Getty Museum, insisted that the vision for the site needed to be braver. Irwin’s designs for the Central Garden had raised the stakes for the whole site. The despised Palo Verde trees were removed and planted elsewhere on the site, and the cactus garden won the day. By this time construction was complete, however, and access to the site so difficult that it was necessary to have a garden that could be installed entirely by hand without the help of cranes or loaders. For installation, the barrel cactus-even the little eight-year-old ones that were used at the site weighed between twenty-five and fifty pounds—were carefully wrapped in newspaper and burlap and then rigged so that they could be carried on the backs of the workers who had to climb up the rugged slope to the terrace. Access to the site, and consequently the ability to change plants in and out, would be a perpetual challenge. The garden was thus planned and executed as a stable display for instant effect.

Fig. 4: View of upper terrace of cactus garden, Getty Center, Los Angeles, 2005 [Photo: Patricia Kikuchi]

Dennis McGlade, of the Olin Partnership (the landscape firm responsible for the final design) kindly shared his recollections of the project with me. He explained that the office’s approach at the Getty site was to let the different spaces provide inspiration. Here the exposed, south-facing promontory invoked heat, sunshine, and expansive views. He wanted to intensify these effects—make them more hyperbolic. One thing the designers liked was the way the upright forms of the cactus echoed the tall buildings of the distant skyline. McGlade limited the plantings to succulents, which are arranged loosely by global origin, adding a pedagogical component. The upper terraces are mainly old-world plants: Aloe bainessi from South Africa for example, a dwarf form of tree aloe that grows up to fifteen feet and has to be trimmed to stay small. On the promontory itself the plants are new world from the western hemisphere, ‘real’ cactus (fig. 5): Euphorbia candelabrum (newly named Euphorbia ingens ) from Mexico; Pachanoi trichocereus from Ecuador and Cereus peruviana or night-blooming cereus from South America; Opuntia robusta, or prickly pear cactus from Mexico; and the vivid red-tinted Opuntia santa-rita —common name being dollar cactus—which comes from Texas and Arizona and is at its deepest purple when it gets the least water—these were grown from cuttings. Included of course is the Agave americana ‘Marginata’, or the century plant, from Mexico and the famous seed-grown Echinocactus grusonii, or golden barrel cactus from Mexico and the south-western United States.

Fig. 5: Details of cactus garden, Getty Center, Los Angeles, 2005

Left: Echinocactus grusonii (golden barrel cactus)

Right: Agave americana marginata (century plant), Opuntia robusta (prickly pear), and Opuntia santa-rita (dollar cactus) [Photos: Patricia Kikuchi]

They are set out in a soil mixture of ninety percent sand mixed with worm castings, topped with two inches of gravel mulch from a quarry near San Diego. The quarry has since closed and it has proven difficult to find a source to match the pinky beige colour—the new gravel is rather greyer but blends in well enough. This gravel and the silver blue senecio provide subtle even backgrounds for the composition of cactus, and effectively hide the drip irrigation system. The irrigation system was used in getting the plants established but has not been used in the past three years. These are drought-tolerant plants, and there is more than enough rain for them to get by in the Mediterranean climate of Los Angeles.

When the Getty Center opened risk assessment experts deemed the south promontory too precarious, too dangerous even to allow staff access past one hundred feet from the edge. The surrounding wall is only about a foot high, affording little fall protection given the deadly steep drop. It was three years until a bronze guardrail was installed, and during this period nobody, not a single gardener, was allowed onto the lower terrace. The garden took care of itself remarkably well for three years, but is now undergoing a good cleanup. The Agave americana ‘Marginata’, for example, which grows from the crown is now being trimmed from the bottom. This sprucing up really emphasizes its radial sculptural form. The restoration project also involves repositioning and adding thirty-four more barrel cactus so that the planting comes evenly up to the walls with only a foot of clearance to allow the gardeners to pass. There is already blue senecio growing amidst the cactus, and more will be added to cover the ground to create a more even background effect.

One might wonder why plants that were native to California deserts like the Mojave were not the ones chosen for the Getty. As it happens, the local desert plants are adapted for extreme desert conditions. The natives are viciously armed, aggressive, and dangerous. Nobody, especially unsuspecting museum visitors, ought to be in immediate proximity to such well-defended plants. The euphorbia ‘sticks on fire’ has a poisonous juice that burns and can cause temporary blindness—American Indians used it to poison their arrows. The teddy bear cholla, Cylindropuntia bigelovii, so called on account of its inviting cuddly-looking golden fuzz, is also called jumping cholla for its habit, given the slightest breeze of a passerby, to break off pieces that stick hundreds of needles viciously and agonisingly into bare skin. But even some of the succulents that were selected for the garden are hazardous. The Agave americana ‘Marginata’ has a highly irritating sap; and the Opuntia robusta, with its charming Mickey Mouse-like paddles, has to be wet down before the paddles can be pruned in order to avoid inhaling the needles. The Getty gardeners wear protective suits with tough kneepads and welding gloves to prevent injuries.

Fig. 6: Left, top: Opuntia santa-rita (dollar cactus)

Left, bottom: Agave americana ‘Marginata’ (century plant)

Right: Michael DeHart, Getty Center horticulturalist in protective gear

[Photos: Patricia Kikuchi]

Designer Dennis McGlade recalled that for him the challenge was to create a design for the cactus garden that was dramatic, strong, and unusual enough to hold its own against the extraordinary vista. It required a composition that was geometric, simple, and strong. Dense massing of a single kind of plant allowed for clearly demarcated areas of unified colour and texture, each section contrasting with the one adjacent. Many of the individual plants are forceful sculptural elements, and their repetition in the beds and limited colour palette create powerful effects. The designers visited the ranch of the California Cactus Center, where they liked the sight of the cactus growing in straight rows across the planting beds. No doubt this was a source of inspiration for the design.

The Getty cactus garden is perhaps even more unusual when considered in context than in isolation. Southern California has a long tradition of desert gardens, the first we know being from around 1880. By the 1920s there were already two journals dedicated to the subject and published in Los Angeles : Desert Plant Life, and the Journal of the Cactus and Succulent Society of America. Cactus makes sense for the climate, since southern California is in large part desert, though coastal Los Angeles has a Mediterranean climate and can have significant rainfall in winter. Southern California is a terrestrial paradise arable and habitable only because around 1915 agricultural interests and real estate developers built the aqueducts that brought fresh water to the region. Who can forget the movie Chinatown ? Much was at stake in the building of the Owens Valley Aqueduct. Los Angeles ‘s fragility and need for imported water were very much on McGlade’s mind when he pressed for a scheme of cactus and succulents that can live and thrive without dependence on water.

It must be said that the Getty cactus garden is quite different in its aesthetics, aims, and type than any other notable cactus garden in southern California. For better or for worse, desert gardens have tended to become botanical arks—for until relatively recently so many of the plants were collected—over-collected from their habitats. Now, of course, the emphasis is on seed and vegetative propagation rather than depleting the habitat. All of the plants in the Getty’s garden were either seed grown or vegetally propagated.

The Getty is also entirely different from the nearby Huntington desert garden, surely one of the greatest examples in the world. The Huntington desert garden is a botanical collection—planned for serious study and education as well as enjoyment. It should also be pointed out that the design of the Huntington, as of other southern California cactus gardens, is assimilated to more traditional historical and picturesque effects. Plantings of cactus and succulents are made to stand in for small trees and shrubs, in mixed beds, along walks, in drifts and compositions that seem to warmly naturalize and normalize them as plants. A familiar planting style tends to mitigate their weirdness. The stark geometry of the Getty cactus garden is a radical departure from this tradition, and that is why the Getty cactus garden does not please everyone. Gary Lyons, the most prominent expert on California desert gardens, prefaces his description of the Getty cactus garden in Desert Gardens(2000) by remarking on the sense of danger and desolation he felt upon encountering the garden:

… masses of golden barrel cacti are set out like a commercial growing ground appearing to hold off an attack of variegated century plants, with pincer-like sweep of hallucinogenic San Pedro cactus (Trichocereus pacanoi ) pushing from one side and oozing masses of prickly pear from the other cutting off all hope of escape. I feel sorry for the gardeners who must maintain these unnatural associations.

What offends Lyons is precisely what I like best about the Getty cactus garden: I find the site not desolate but electrifying. The edge of danger intensifies the experience. Like Lyons, I too find that visiting these platoons of small cactus, these unrelieved, full-strength beds of oddly formed succulents, does feel a little like a journey to another planet. But I find the exoticism to be alluring. Rather than normalizing the unearthly character of the cactus, the design lets us admire its radical strangeness.

Gail Feigenbaum is the Associate Director at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

Acknowledgements:

Michael DeHart (suited for action in fig. 6) and Lynn Tjomsland, the Getty’s head gardener helped me enormously up a very steep learning curve to prepare this piece. I would also like to acknowledge the help of Catherine Phillips of the Huntington, a brilliant guide to the uncanny desert world of living rocks and succulents that she tends with rare skill.