By Danielle Fuller and DeNel Rehberg Sedo

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version.

Danielle Fuller: Tell me about ‘the wow factor’.

Angela Caretta: Oh that’s when you get to some part in the book and you say ‘wow!’

(Group interview with organizers of ‘One Book, One Community Kitchener-Waterloo-Cambridge’, July 2003)

Large-scale shared reading events that employ the ‘One Book, One Community’ model (OBOC) present reading studies scholars with a fascinating example of contemporary reading culture. Initiated in Seattle in 1998 by two Reader Advisory (RA) librarians, Nancy Pearl and Chris Higashi, OBOC usually consists of a program of events running across a period of three to six months and focuses on the content, themes and contexts of a selected text, often, but not always, a work of fiction. The geographic scale of each program is generally indicated in the title, for example, ‘Seattle Reads’, ‘One Book, One Vancouver’, ‘Nederland Leest’, and ‘One Book, One Madison County’. While the explicit aim of most iterations of OBOC are to encourage as many people as possible to read and share their experiences of reading the selected book, programmed activities do not always assume familiarity with the text or even demand that participants possess print literacy. Screenings of film adaptations, theatrical dramatizations, and staged readings of extracts from the book by professional actors or local celebrities are common to various iterations of the model. One-off book group discussions, talks by experts, panel discussions and a series of live events featuring the author are other typical features of OBOC. Local histories, cultures and physical sites (such as iconic buildings, or natural landscape features) may also be employed by organizers through activities that connect the world of the book to that beyond the text. From pub-crawls to walking-tours, from camp-outs in city parks to canoe trips down rivers, and from painting workshops for children to talks about Italian wine for adults, OBOC organizers around the world have been creative about using their local natural and human resources to construct programs that might appeal to people who are not already confirmed leisure readers. The opportunity to participate online is also offered by most programs, but, in the mid- to late-2000s, when we were investigating OBOC events, the extent of interactivity was frequently limited by budget constraints.1 Nevertheless, the flexibility of the OBOC model, especially the fact that it can be adapted by organizers if funding is limited, means that the model has been widely replicated. Versions of OBOC have taken place not only in the United States and Canada, but also in the United Kingdom, continental Europe, Singapore and Australia. Although it is impossible to provide an exact figure, we estimate that more than five hundred OBOC programs take place annually around the world.2 In Spring 2010, OBOC even entered the ‘Twittersphere’.

As a product of what we have conceptualized elsewhere as the reading industry (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo 15-27), OBOC embodies the fusion of popular forms of entertainment with the reading and sharing of selected books as a social practice (27-32; 206-10). The ‘wow factor’ referred to above by Angela Caretta, a Canadian public librarian who is a member of a OBOC organizing committee, not only articulates that fusion, but also suggests the desire on the part of the cultural worker to reproduce a particular kind of reading experience for other readers. In this article, we employ two brief case studies in order to illustrate the various constructions of value attached to literary texts and to the act of reading that the OBOC model can put into circulation. The program that Angela Caretta has helped to build in southern Ontario—‘One Book, One Community- Kitchener-Waterloo-Cambridge’ (OBOCKWC) (2002-present)—along with ‘One Book, One Chicago’ (2001- present) are among the longest-running versions of this type of city-wide reading event.3 While their longevity as recurring programs suggests that they are successful, our research into early iterations of both programs revealed the sometimes troubled negotiations around notions of value involved on the part of both organizers and readers. In Canada, the organizers of OBKWC nominated ‘the wow factor’ as a crucial criterion for their book selection. But it became clear to us that the members of the organizing committee had different ideas about the type and value of reading experience that they were seeking to produce or re-produce for readers. Meanwhile, in Chicago (2005), the selection of Pride and Prejudice for the Fall version of OBOC produced tensions among the elite regime of value attached to the history of this particular literary-canonical text; the socio-cultural transformative value of reading; and the economic benefits for publishers, booksellers and even film-makers of promoting the selected book in various media. Several readers we met recognized and negotiated with these values in creative—and sometimes surprising—ways. Examining some of these negotiations around the value of reading—and of sharing—fictional texts does not ‘reveal the reader’, rather, such a practice represents an intriguing critical pathway for exploring one aspect of a contemporary reading culture that is shaped by production and cultural policy issues as well as by readers’ desires to encounter other readers. We therefore suggest that interrogating the ways that cultural managers frame and promote reading events should occur alongside an investigation of the uses that readers make of them.

Searching for ‘the wow factor’ in Southern Ontario

‘One Book, One Community—Kitchener-Waterloo-Cambridge’ encompasses three small cities in southern Ontario which have a combined population of 477, 160 (Stats Canada Census). Waterloo is home to two universities and a research-based communications technology industry supported in part by Research In Motion (RIM) a company created by the inventors of the Blackberry, and sponsors of the RIM Institute. During the first decade of the twenty-first century Waterloo was the most economically prosperous of the three cities, and, unlike Cambridge and Kitchener, its population was growing. When the OBOC program was started in 2002, the presence of a ‘reading class’4 was most marked in Waterloo, which at that time was home to thirteen bookstores, for example, compared to six in Cambridge, and ten in Kitchener (which remains the biggest of the three cities in terms of population size). There were lower levels of education and literacy among the residents of Cambridge and Kitchener than among those living in Waterloo (Stats Canada Education). While Kitchener main public library had garnered a reputation for a vibrant and well-attended program of book events aimed at adults, Angela Caretta, the librarian on the OBOC representing Cambridge, noted that public library resources for her city were focussed primarily on programming for children prior to the inaugural event of the citywide read.

The socio-economic and cultural differences among the three cities should also be situated within a wider political context of successive funding cuts to the arts and culture at both provincial and federal levels in Canada. As the late cultural critic and feminist scholar Barbara Godard documented in a series of articles, these cuts, the first round of which occurred in the mid-late 1990s, were both material and ideological in their effects (‘Privatizing the Public’; ‘Feminist Speculations’; ‘Upping the Anti’). Not only did the reduced funding sweep away much of the literary-cultural infrastructure constructed in the decades following the Massey-Lévesque Commission (Report), but the cuts were driven by a business model predicated on a for-profit conceptualization of Canadian arts, rather than on a notion of culture inflected by ideals of democratic access to the means of expression and production (Fuller 16). What this meant for the organizers of OBOCKWC in 2002 is that they were designing their shared reading program within what we will broadly characterize here as a neoliberal political climate. As we have analysed in detail elsewhere, the emergence of neoliberal notions of cultural value (explicitly articulated in cultural policy documents, for example) have put the cultural managers of arts organisations and of public sector services like libraries, under pressure to deliver programs and artefacts that can be accounted for in both economic and social terms (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo 129-32; 150-1; 160-1). Simply put, from the standpoint of governing agents, culture is expected not only to pay its own way as much as possible, but also to assume some of the social roles previously enacted by social and community-based services that have also been subjected to reductions in funding. Indeed, the One Book One Community model is in many ways, as we have argued previously, a perfect expression of its neoliberal socio-political context (162). That said each version or iteration of the model creates opportunities for the organizers and participants to negotiate with the constraints and values imbricated within it, including its apparently top-down and hierarchical structure. For example, an organizing committee usually selects the book rather than putting the choice to a public vote, and their assumptions about the value of particular books and specific ways of reading them can—as we explore below—shape the framing of events in particular ways. At times, such event frames may emphasise learning rather than entertainment or pleasure, as our second case study illustrates. Nevertheless, neither the ways that organizers value reading, nor the socio-political situation of the OBOC model can entirely determine the kind of community that may form or come together (or fail to form or come together) as a result of a citywide reading event.

Many versions of OBOC in North America are organized or led by professional librarians but OBOCKWC has from the beginning been managed by an alliance of representatives from public sector, for-profit and not-for-profit organizations. The organizing committee, an overwhelming majority of whom are women, consists of several public librarians, an independent bookseller, the editors of The New Quarterly (a literary journal), a representative of the city of Waterloo, and occasional co-opted members, including school teachers and high school students. The committee list among their criteria for OBOC book selection, the necessity of choosing a Canadian book by an author willing to spend three days in the community at the end of the program (usually in September); a book that will be of interest to men and women of different generations, and a book that possesses ‘the wow factor’. The ‘wow factor’ is an intriguingly imprecise (almost) non-verbal descriptor that suggests how a book might impress, excite or amaze a reader. Angela Caretta, a founding member of the committee and a professionally-trained public librarian working in Cambridge, understands ‘the wow factor’ as an intra-textual phenomenon capable of provoking a reading experience that can be emotional, cognitive-intellectual or even quasi-spiritual:

Danielle: Tell me about ‘the wow factor’.

Angela: Oh that’s when you get to some part in the book and you say ‘wow!’ I guess that it’s an aspect of the book that engages you not just as, you know, the reader of a narrative, but engages your heart or engages your mind or engages your soul or makes you want to say to your you know, [friend] ‘did you read this?’ ‘It’s such a good book because…’ or, ‘I really enjoyed this part of this book’ or so, that’s how I see ‘the wow factor’.5

For Caretta, ‘wow’ denotes an intensity of engagement on the part of the reader.6 While her commentary does not appear to privilege one mode of engagement over another, the ability of a book to inspire the social act of sharing an arresting scene or image with another person (who may or may not become a reader of the same book) is clearly important to the OBOCKWC committee’s adaptation of the OBOC model.

Sharron Smith, another founding-committee member and a RA Librarian at the downtown Kitchener public library, indicates how the committee’s notion of ‘the wow factor’ was informed by their experiences of interacting with readers during the first iteration of the program in April-September 2002 when their selection was Alistair MacLeod’s novel No Great Mischief, a critically-acclaimed, international bestseller:

Another thing that’s important in what we look for in a book [is] that it’s accessible… by accessible it’s that yes, it’s readable, it’s approachable and that it can reach out as Angela says and touch you, so that, and that’s where the conversation then begins because you’re then able to say, you know. … In No Great Mischief I think the passage that so many people commented about is the Christmas passage where, you know, the grandfather is drunk and they decorate him with Christmas lights. And, and people talked about that far and wide you know and how, and then talked about how—cause every family has their Christmas stories, you know—and so, that connected, that resonated with readers. And, you know, I think that we’re hoping for that… (Smith)

Smith, an experienced and locally admired book group leader, identifies a suitable OBOC selection as an ‘approachable’ book that moves the reader beyond a private, internalized textual engagement towards an extra-textual encounter. The ‘wow factor’ may operate in the first reading of the book, but its affect/effect needs to exceed that initial site and moment of reading. In book group parlance, the ‘discussability’ of a book is also key to a successful meeting, since readers need to be able to move beyond expressing simple approval for or rejection of a selected title into an exploration of how the text engages (or fails to engage) them (Taylor ‘Good for What?’; ‘Readers’ Advisory’). Smith’s example illustrates her understanding of how MacLeod’s fictional narrative connected to readers’ everyday lives via memories and experiences, prompting the generation and sharing of their own ‘Christmas stories’. The concentration on Christmas pinpoints the cultural specificity of that particular textual encounter, as well as indicating the limits of the demographic for OBOCKWC’s first OBOC audience. Kitchener-Waterloo is, in fact, home to a significant minority of people who would probably not celebrate Christmas. As the fourth-largest immigrant reception centre in Canada, its population is more culturally and ethnically diverse than the focus of local enthusiasm for MacLeod’s fiction about a Scots-Canadian family might imply.

Regardless of the various challenges involved in selecting a book with community-wide appeal, ‘the wow factor’ is significant to an analysis of the meanings and the value readers ascribe to the act of reading. It captures the OBOCKWC committee members’ shared belief in a reading experience of text-inspired excess that manifests as various forms of pleasure. They wish to reproduce these intense reading acts for other readers and community members because the pleasure is not always only a private, solitary or interior experience: it can exceed it to become a profoundly social, shared act of re-reading (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo, Reading Beyond the Book 27-32;237-9). As Smith’s and Caretta’s comments imply, their experiential knowledge as avid readers combines with their professional knowledge about readers’ tastes to shape their understanding of a successful OBOC selection. Unlike ‘One Book, One Chicago’ and ‘One Book, One Vancouver’, two other long-running versions of the model, OBOCKWC is not a library-driven program and the members of its organizing committee bring different knowledge about books and reading cultures, communities and social action to the table.

Not surprisingly, given their training and professional situation, the librarians and ex-teachers on the organizing committee cherish the ideal of increasing print literacy. However, the collectively-negotiated vision for their OBOCKWC program as articulated by its instigator, Tricia Siemens, is to ‘build community through reading’. For Siemens, shared reading has a social objective: it offers a ‘shared experience’. The tension among different ideological positions on reading are rendered visible in the publicity designed for the early years of the OBOCKWC program and its ambiguous messages about self-transformation. The challenge of ‘building community’ through an activity that, within Euramerican cultures, is frequently conceptualized as a solitary, private activity, emerges in the contradictory messages constructed by the publicity for the program.

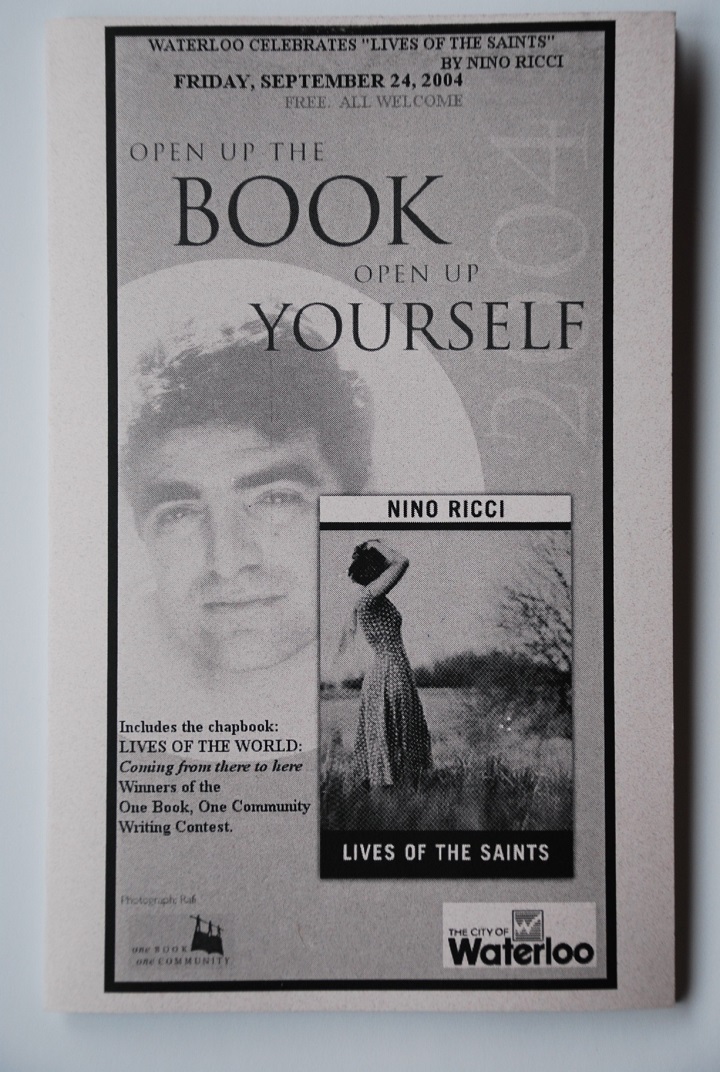

Figure 1: A photocopied chapbook of local writing illustrates the OBOCKWC logo and community involvement. (Source: Authors’ collection)

The tag-line for the first three years of the program (2002-4), for instance, was: ‘Open Up the Book, Open Up Yourself’. (See Fig. 1) The slogan appears to adopt the discourse of self-help identified by Trysh Travis in her examination of the reading strategies employed by US book groups in their engagements with Rebecca Wells’ Secrets of the Ya Ya Sisterhood (134-161). Travis delineates collective reading of Wells’ book as a form of therapy or self-help evangelism that obscures social history, structural inequalities and political activism by foregrounding the capacity of the individual to recover herself (137-8). In an apparent contrast to this, OBOCKWC publicity underlines the importance of collective reading as a ‘shared experience’. Within the committee’s conceptualization of ‘shared reading’, the community acts as a type of translator of the private, individual act of reading and the understanding of subjectivity and everyday experience that it enables, into a search for common grounds of knowing. ‘Once people have read the same book’, says Tricia Siemens, ‘They talk to friends and neighbours about how the story resonates in each of their lives’ (Greeno). The organizers wish to promote a reading practice that is dialogic because it needs to be heard by a community of reader-listeners. In this sense, the ‘shared experience’ of talking about a book with other people does not rule out the possibility that the individual reading experience may in itself be transformative or therapeutic. However, the tag-line ‘Open Up the Book, Open Up Yourself’, which loomed large on bookmarks and posters for the program between 2002-4, displaces the committee’s emphasis on ‘build[ing] community through reading’. Given the mass media’s association of sharing reading, particularly in the context of book clubs, with women the OBOCKWC poster message can also be interpreted as assuming a feminine interlocutor. Siemens herself noted this gendered notion of reading as individually and emotionally transformative in a ‘Wrap-Up’ meeting for the 2004 program that focussed on Nino Ricci’s novel Lives of the Saints: ‘That tag-line was a mistake. That’s not a guy thing…guy’s don’t open up themselves’

Not only do the committee have to wrestle with the potentially exclusive effects for their program of gendered assumptions about reading, they also have to negotiate with taste hierarchies and their own competing notions of literary value in relation to the aims of OBOCKWC. In common with other OBOC organizers we interviewed, the OBOCKWC committee are self-confessed keen readers (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo 137-8; 164-204). There also appears to be nothing unusual about their literary tastes if we compare them to those of other people working within similar professional arenas. Within our trans-national survey of readers,7 contemporary fiction was chosen as the most frequently read genre by more than a third of librarians (37.1%), educators (42.8%) and those who work within the arts and media (38.8%). Although a significant number of librarians chose mystery as their favourite genre to read (21%), a relatively small proportion of the educators chose mystery (9.6%) or science fiction (9.6%), while slightly more arts and media workers selected classic literature (7.2%) than opted for sci-fi (6.6%). Classic texts are also favoured by some librarians (6.9%) and educators (8.3%). Not surprisingly, perhaps, the majority of the books selected for the OBOC programs we have investigated fall squarely into these four favourite genres (that is, contemporary fiction, mystery, classic literature and science fiction). Where programs often differ is on national grounds, with organizing committees choosing, for example, a British novelist for a UK-based city-wide read (e.g. Andrea Levy’s Small Island in Liverpool, UK, 2007) or a contemporary American writer such as Julia Alvarez (In the Time of the Butterflies, Fall 2004) in Chicago. As noted above, for the KWC version of OBOC, selecting a living Canadian writer who can visit the region is central to the type of shared reading experience which the organizers wish to produce for their community: but, are they simply reproducing their own sense of literary value and taste?

Cultural workers and managers—or cultural mediators as Bourdieu termed them—do not, as David Wright has suggested—‘mediate between cultural production and consumption in benign ways. … Rather, their work reflects the interplay, inherent in contemporary cultural production, between generating new styles of life and protecting established hierarchies of cultural value’ (Wright 106). Reading event organizers, whether they work for commercial or non-profit organizations, are agents within the reading industry and, as such, must contend with market logics, public sector mission statements about the ‘public good’, and government rhetoric about cultural citizenship and cultural value (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo 23; 136-8; 168-9). The mixed-agency organizing committee of OBOCKWC demonstrate an explicit recognition and negotiation of their roles as mediators of the meanings of reading and, more specifically, of genre preferences. In the ‘Wrap-Up’ meeting held in November 2004, Angela Caretta, the Cambridge librarian, began to delineate taste preferences and taste hierarchies among library patrons. She noted how her library serves many readers of genre fiction whose familiarity with the codes of, for example, thrillers, westerns or romances, influenced their engagement or, rather, their non-engagement with the literary fiction selected for the first three years of OBOCKWC: MacLeod’s No Great Mischief, Jane Urquhart’s The Stone Carvers, and Nino Ricci’s Lives of the Saints. These book selections are all prize-winning works of contemporary realist literary fiction with narratives that centre on the experiences of Gaelic, Anglo-Canadian and Italian peoples respectively. MacLeod’s and Urquhart’s novels have ties to the region through the depiction of local places, while Lives of the Saints, although set entirely in Italy, is connected to the region via its author whose family still live in nearby Leamington, Ontario. Despite these potential points of entry into the narrative, Caretta noted that for many library users, these realist novels, prized by fans of literary fiction for their use of language, ‘might still be quite inaccessible’.

Indeed, our research in KWC suggested that it was active readers of literary fiction who participated in events during the program’s first three years, even if they had not read the selected book.8 Of the 97 respondents to the online survey, about half (52%) of the people participating in the KWC survey belonged to book clubs, and over a third (37%) reported reading between six and 10 hours a week. Moreover, the majority of respondents were readers who probably felt comfortable with the OBOC selections since ‘contemporary fiction’ was their favourite genre. One anonymous reader even articulated the key qualities sought out by the organizing committee for the selected book:

It has to be a book that encourages discussion, and has broad appeal. No Great Mischief by Alistair MacLeod had a lot of different themes, was beautifully written, appealed to men and women, talked about different parts of Canada, etc.

To extend the logic of Siemens’s comment about the similarity between OBOC participants and committee members, the 2004 program appeared to reproduce not only the visible identities of the cultural workers, but also their literary taste. This finding suggests that the early versions of OBOCKWC were attracting readers who belonged to existing reading communities such as book clubs, or the more loosely affiliated audience who attended Kitchener main library’s program of events, or Tricia Siemens’ bookstore-located author events. But the first OBOC visibly included another existing interpretive community—that of senior high school children who were reading MacLeod’s novel as part of their curriculum. Part of the value of the earlier iterations of the model, then, lay in the consolidation of extant communities by offering public spaces and events that enabled existing reading communities of various kinds and of different age demographics to meet together to form a visible network of readers. Of course, the rather limited reach of the model between 2002-2004 undermines the rhetoric of equality and participation implied in its name. Put bluntly, the kind of community desired by the organizers did not always materialise. However, as we discuss below, in succeeding years the committee used different book choices and variations in the programming as a way of attracting a more heterogeneous audience, and of opening up access to OBOCKWC for those who were not already confirmed readers of literary fiction.

Given that our survey respondents can be described as keen readers, it is not surprising that their perceptions about the aims of the OBOCKWC program also resonated with those of the organizers. When asked what they thought OBOC should achieve, our KWC respondents’ top three choices among the options offered were: ‘Encourages people to read books they wouldn’t normally read’; ‘Motivates people to read’, and ‘Encourages them to talk about what they’re reading’. While Angela Caretta questioned the first objective, her committee colleagues, including her sister librarians, were more at ease with the idea that KWC readers might be lured into reading an unfamiliar literary novel. By attempting to introduce people to books they may not choose for themselves, the organizers can aim to ‘generat[e] new styles of life’ through their encouragement of community participation in a new cultural formation. At the same time, the organizers could be understood to be ‘protecting established hierarchies of cultural value’ by selecting books which have already been consecrated as worthwhile by prize juries and literary journalists (Wright 106). However, their book choices and actions are not inherently negative or positive in their effects, but rather appear to embody the contradictions bound up in the project of employing a prestige-laden activity (book reading) to promote cultural participation across a city’s—or region’s—diverse population (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo 2-3; 248-58). Within the context of Kitchener-Waterloo-Cambridge, as already noted above, for example, levels of education and literacy among the population are varied. How can one book choice ever cut across these differences? The promise of inclusion and democratic access bound up in the name of the program can thus be very difficult for organizers to deliver ‘on the ground’. The selection of prize-winning literary fiction titles—some of which may be considered highbrow —may limit the size of the OBOC audience while simultaneously enabling some people to try something new. In this sense, choosing an already consecrated work of literary fiction is not necessarily a conservative action on the part of an organizing committee. On the other hand, selecting a mass market book that may be accessible to a bigger audience could be deemed to be a conservative move if it merely reproduces choices that participating readers would have chosen for themselves without the program. That the organizers were aware of their own habitus, understood existing cultural hierarchies and the necessity of negotiating with them, becomes clear from our analysis of the ‘Wrap Up’ meeting below.

In addition to differentiating between the reader-participants who were motivated to read the OBOCKWC selections and the majority of her library clients, Caretta recognized the different levels of cultural capital within the organizing committee itself during their 2004 ‘Wrap-Up’ meeting. Turning to Kim Jernigan, the unpaid editor of the literary journal, the New Quarterly, she commented: ‘we’re [the librarians] not as high as you, but we’re higher than most of our patrons and they’re not interested in moving up; they’re interested in reading for pleasure and enjoyment’. Sharron Smith, however, countered Caretta’s suggestion that readers should not necessarily be encouraged by librarians to read books that will increase their cultural capital and expand their knowledge. In support of her view she offered stories of her Canadian Literature book group whom she has introduced to a range of (mostly) contemporary novels that they have both enjoyed and felt challenged by. Although the librarians on the committee share their professional training and possess similar amounts of work experience, they are differently positioned in relation to adult readers, particularly in terms of the amount of symbolic capital they have accumulated as ‘guides’ and ‘advisors’ about reading choices. Smith, for example, has become a multi-media reader development librarian with a regular local radio and cable TV segment on books. She is also the co-author with Maureen O’Connor of Canadian Fiction: A Guide to Reading Interests, a volume in the influential genreflecting book series catering primarily for RA librarians working in North America. Smith’s achievements and her successful organization of professional conferences for RA colleagues were recognized at the provincial level when the Ontario Library Association named her as Librarian of the Year for 2008. She is, in the professional sense, something of a model for her peers, as a twenty-first-century public librarian who is media-savvy and well networked.

While the public librarians on the committee may ascribe different values to the power of literary fiction to engage library patrons, literary journal editor Kim Jernigan recognized the potential of OBOCKWC to take shared reading outside library walls and into spaces and places where the meanings of reading are not usually brokered. Jernigan’s knowledge of canonical aesthetics and her attraction to vernacular forms of reading, including the pleasures of reading aloud and being read to, have inflected the sites and social dynamic of the OBOCKWC events sponsored by the New Quarterly. These have ranged from a literary pub crawl and a canoe trip, each of which incorporated short readings from the selected book by local celebrities, to bus tours around sites associated with the setting of a text or with aspects of its author’s biography. Jernigan’s literary cultural capital also informs her analysis of the competing agendas of the committee. She ably articulated the different aims envisaged within the committee as ‘wanting to get people to read and discuss [specific kinds of] books [versus] wanting to get more people involved with the community through reading’. She also suggested to her colleagues that reading and discussing a book is actually ‘an academic model’ for sharing reading and she offered the ‘Wrap-Up’ meeting a model that is ‘performance-based or music-based’ as an alternative that might operate more inclusively, by appealing to people for whom printed books are not the art-form or medium of first choice. Since 2004, the OBOCKWC organizers have experimented with a wider variety of events, from talks on topical science issues to accompany the 2005 selection of Hominids, a sci-fi novel, toorganic vegetable-growing inspired by the program’s first non-fiction selection, Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon’s The 100-Mile Diet in 2008. Both the events and these book choices indicate the committee’s efforts to move beyond the mediation of their own literary tastes in order to extend the cultural work that their version of OBOC might perform, such as generating public debate in their community about climate change and other ‘green’ issues. Selecting different genres also increases the appeal of OBOC to readers, like Angela Caretta’s library patrons, for whom literary fiction may seem too ‘inaccessible’. Taking up a range of genres—including a mystery book (Louise Penney’s Bury Your Dead was the 2011 selection) and a memoir about travel (Allen Casey’s Lakeland in 2013)—can also be understood as an attempt to involve readers from different demographics, such as young adults and men, as participants.

The OBOCKWC case study offers a glimpse into the social and ideological situation of a group of cultural workers who have collaborated effectively for more than 10 years. While they are empowered as arbiters of literary taste within the book selection process for OBOCKWC, they are variously invested in genre hierarchies, are advocates of different models of reading (academic and vernacular), and place varying degrees of emphasis upon the values of the program (creating community, encouraging readers to be more adventurous). Their competing views on the role of OBOCKWC and, indeed, on their role as mediators of books and reading, created some productive negotiations about the values of reading. Between 2002 and 2014 a wider range of book genres and activities have formed part of OBOCKWC. Subsequently the all-important book selection criterion of ‘the wow factor’ has, perhaps, become less attached to the idea of reproducing a moment of intense emotional engagement for an individual reader, and more about producing an entertaining and varied program for a diverse constituency of leisure readers. But how do OBOC participants respond to the book selections and events, and what do they perceive to be the value of this twenty-first-century cultural formation of shared reading? In order to examine some of the factors at play, we turn to our second brief case study.

Chicago reads Pride and Prejudice

One Book, One Chicago encourages all Chicagoans to read the same book at the same time and to gather together in discussion with friends and neighbours.

(Richard M. Daley, Mayor. Pride and Prejudice resource guide)

Although not the first ‘One Book, One Community’ program to be staged in the USA, ‘One Book, One Chicago’ (2001-present) is probably the best-known city-wide reading program in North America. It was also the direct inspiration for Australia’s ‘One Book, One Brisbane’ (2002-present), the BBC’s ‘The Big Read’ (2003) and Bristol’s ‘Great Reading Adventure’ (2003-2010 and 2014). Since Fall 2001, the program has run twice a year in October and April, and has a full-time organizer who is also the director of the Book Festival and usually a member of Chicago Public library staff. The press launch is always fronted by the mayor, who, as indicated by the quotation above, also introduces the reader’s resource guide which is available online and as a colourful 20-page pamphlet. It was in fact Mayor Richard M. Daley who, in 2000, challenged the city’s librarians and teachers to find a way of reversing the low reading scores in the city’s schools, and who loved the idea of ‘One Book, One Chicago’ so much that he insisted that it run twice a year. So attached was he to the program and to the symbolic value of being the Mayor who is passionate about literacy and reading, that the Fall 2005 book choice announcement was delayed by over two weeks while he was in court on corruption charges.

The Mayor’s enthusiasm for the ‘One Book, One Chicago’ program may well have been fuelled by the need for a twice yearly ‘good news’ story—and not only because of his own political troubles. In 2002, Steven Leavitt and Brian Jacob published the results of their study into teacher cheating based on Chicago public school tests taken between 1993 and 2000. As reported by Lois Beckett, ‘Cheating on standardized tests occurred in at least 4 percent to 5 percent of classrooms every year; teachers in low-performing classrooms were likelier to cheat; and a “pronounced spike” in cheating occurred when Chicago introduced high-stakes testing in 1996’. The falsification of results by school authorities received nation-wide media coverage (Gabriel), and the negative news about the Chicago Public School System continued as the City closed 38 schools between 2001 and 2006 (de la Torre and Gwynee 5). The majority of closures were due to low enrolment relative to their capacity, but nine schools were shut down due to ‘chronic underperformance’. In June 2004 Mayor Daley launched his Renaissance 2010 plan whose goal was to close ‘troubled’ schools, and replace them with 100 charter and privatised schools by 2010. While this scheme met with much opposition from within various Chicago neighbourhoods (Freedman), it neatly exemplifies how Daley’s educational policy was shaped by a wider neoliberal political context in which public funding to social and welfare services—including education —was being cut. Media-friendly programs such as Mayor Daley’s Teen Book Clubs9 and ‘One Book, One Chicago’, may thus have enabled Richard M. Daley to recoup some credibility as a leader who oversaw investment in educationally-oriented pursuits. By encouraging Chicagoans ‘to gather together in discussion [about the selected book] with neighbors and friends’, Daley was also employing the democratic-sounding rhetoric of the OBOC model to imagine a form of public participation in arts and culture that was, in fact, increasingly under threat from his own policies and funding cuts. But such apparent contradictions and inconsistent logic are, as Stuart Hall reminded us, typical of neoliberal governments (17).

Once his trial was over and jail avoided, Mayor Daley was able to launch the Fall 2005 iteration of ‘One Book, One Chicago’. In a departure from the American-authored choices that had ranged from modern classics such as Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, to The Coast of Chicago, a collection of contemporary short stories by Chicago-born author Stuart Dybek, the selection for Fall 2005 was Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Although ostensibly a high-culture choice because it is part of an institutionally legitimated canon of British literature, the novel has been adapted several times for television and film. Its characters and themes have also been reproduced within several contemporary novels including The Jane Austen Book Club by Karen Joy Fowler, which was first published in the USA in 2004 and which stayed on the New York Times bestseller list for several months of that year. In sum, Pride and Prejudice is not only a book that trails behind it an elite regime of value, it is also a commodity that has become thoroughly imbricated in what Simone Murray terms ‘the adaptation industry’. Rather than confusing or deconstructing notions of high and popular culture that might be associated with different mediations of a text like Pride and Prejudice, however, Murray’s incisive analysis demonstrates how the media industries keep ‘cultural hierarchies … alive’ to serve both commercial and ideological ends (18). Adaptation industry agents ‘push audiences to consume near-identical content across multiple media platforms’, while they ‘constantly reiterat[e] a film-maker’s respect for a content property’s prize-winning literary pedigree’ (18). Thus, the selection of Austen’s novel for ‘One Book, One Chicago’ presented potential participants with various constructions of the text’s value: as a literary-canonical classic book; as an economic and multi-media success story offering a series of possible encounters with the narrative via its adaptations (several film versions and a theatrical adaptation were included as part of the OBOC program); and, as a symbol of the socio-transformative value of reading, and especially of this model of shared reading through which Chicagoans were explicitly encouraged ‘to gather together in discussion with friends and neighbours’ (Chicago Public Library).

Our investigations suggested that participation levels in ‘One Book, One Chicago’ in Fall 2005 were not as high as previous years in which the book selection connected more directly to aspects of the city’s history or to topical social issues. Most respondents (80%) to our online questionnaire that we ran in October 2005 were middle-class women. Our data suggests that book club members were more likely to participate than non-book club members. This may indicate that the Fall 2005 program attracted and involved active, serious readers, but that it was not consistently creating new readers or involving people who had never been to a book-related event before. Our quantitative and qualitative investigations also suggested that the majority of people attending events and/or participating by reading the selected books were white and had English as their first language. Chicago is a city of nearly three million people, where 80.2% of the adult population has attained high school diploma-level education, 32.9% of adult residents identify as black or African-American, and 35.5% of adults speak a language other than English at home (United States Census Bureau). The racially skewed aspect of participation is thus cause for some concern, especially given that the organizers believe the program to be for ‘All Chicagoans … High School and up—everyone in Chicago’ (Allman).

Although the participation in the Fall of 2005 may not have been what it was in previous iterations, we want to focus upon the various ways in which a variety of readers who didparticipate negotiated with these different frames and regimes of value as they read Austen’s novel. In the interests of space, and at the risk of seeming instrumentalist, we offer brief commentary upon three types of reader evaluation: first, the pleasure value of re-reading Austen; second, the rejection of or resistance to the literary-aesthetic value of Pride and Prejudice; and, third, the re-negotiation of the novel’s socio-cultural value within an established textual community. These practices of evaluation and consumption frequently overlap, as we might expect given the multiple encounters with the text that some Chicago readers experienced as a result of watching film adaptations, attending panel discussions and sharing book talk in discussion groups.

Nearly half (47%) of the 125 respondents to our online questionnaire reported that they had read Pride and Prejudice. The library’s own completed evaluation cards indicated a high percentage of re-readers, nearly all of whom were frequent library-goers.10 It is not surprising, then, to hear Pride and Prejudice described by re-readers using the evaluative terms employed in the reader’s resource guide that was written by library staff:

Great choice—can’t go wrong with a classic. Always lessons to be learned. A literary masterpiece.

I’ve enjoyed re-reading the classics. They should be spotlighted in this way. Too many have missed reading them.

A notion of aesthetic value (‘a literary masterpiece’) underlines the novel’s cultural prestige as a ‘classic’ and the institutions that have produced that regime of value are implicitly signalled by the reference to ‘lessons to be learned’ from the novel. For many re-readers of Pride and Prejudice, the value of re-encountering the novel through the ‘One Book, One Chicago’ events, especially book group discussions and the panel presentations that were offered by DePaul University faculty, lies in the reaffirmation of their own literary knowledge and taste: they can recognise a ‘timeless’ piece of Literature and know how to interpret it.11 But they also experience pleasure from the social act of sharing book talk or listening to a dramatic reading. For some re-readers the pleasure is associated with learning, since the events bring ‘a deeper understanding’ or an expanded knowledge of historical context. For others, the pleasure is more ephemeral:

I have read this book at least 8 times so it is like a very old friend. It was interesting to hear new impressions from those who were reading it for the first time, however, I don’t think they influenced my feelings or thoughts in any way.12

These performances of consumption mirror those which occurred in several book discussions in which we were involved as participant-observers. At the Lincoln Belmont Branch Library, for example, we encountered a very literate mixed-gender group of well-educated professionals. Language and narrative structure interested these readers as much as issues of class or historical context. Jerry, a white man in his 60s, thought that Pride and Prejudice was a ‘delightful change’ for ‘One Book, One Chicago’, and wondered, somewhat astutely: ‘is Mayor Daley trying to give cachet to Chicago?!’

Other book discussion groups struggled with the very elements that re-readers and the Lincoln Belmont group enjoyed. In an all-female discussion at Uptown Branch Library, Marie, a white woman in her late 40s, kicked off the book talk by declaring that the language in Pride and Prejudice was ‘more flowery than a gangster’s funeral!’ Meanwhile, Denise found it difficult to empathize with the characters, and thus rejected the novel as ‘superficial’ and ‘boring’. Some of these readers, all fans of genre fiction, had worked hard in an attempt to make sense of an unfamiliar text—Marie had written pages of notes, for example. The group recuperated some social value from a novel that for them held little linguistic or narrative value, by spending a good portion of their allotted time discussing Austen’s representation of work. For Marie, whose busy job was a pre-occupation, this was a means of building a connection with a novel whose aesthetics were unfamiliar and even alienating. Rather differently, a young Chinese-American woman in her 20s from the same group employed her knowledge of the 1995 BBC TV adaptation as an orientation device for the plot, and to help her negotiate difficulties with unfamiliar language and the un-attributed dialogue in the print text. For this reader, who was ‘delighted’ to find specific scenes that she remembered from the TV version in the novel, the value of the print text was contingent on her visual cultural competencies.

Our final example involves a more overt re-negotiation of the novel’s socio-cultural value within an established textual community. The 15- and 16-year old school students at Kenwood Academy High Teen Book Club on the South Side of Chicago are a great example of a textual community negotiating common grounds with Pride and Prejudice so that they could communicate with the text and with each other. In order to locate and articulate the value that Austen’s novel held for their group, they had to work through some of the same obstacles encountered by adult readers, and a shared gut reaction to reject a book that was about, in the words of one young black woman: ‘rich, white upper-class people who have nothing better to do than marry off their daughters’. In a session facilitated by two Book Club members—Joy and Monique—the students encouraged each other to articulate specific difficulties, as well as to share their strategies for overcoming them. One student had visited the Harold Washington Library downtown to borrow an audio-recording that she used to ‘hear’ the characters in her print text; another had begun to compile a glossary of unfamiliar words using the internet. Aware of the Club’s overt rules—the students must discuss the selected book and their teacher-librarian Roz Anderson checks up on them half-way through their session—Joy and Monique were well prepared. Both were impressively skilled at moving on rapidly from lines of enquiry that were not of interest to the group—for example, parallels between the novel and Jane Austen’s life—and then slowing down when they hit upon the topics that enabled the group to work towards a shared notion of the text’s value. Thus, ‘Can you relate it to modern times?’ prompted Bridget to talk about how many girls in the school judged boys by their brands, clothes and muscles; others talked about ‘trends’, ‘following the crowd’ and what happens when you do not join groups or follow fashion. For these students, Elizabeth Bennett was a character who had some energy and intelligence to resist the norms of group behaviour, yet fell into it nevertheless. Their assessment lead into a critically-engaged discussion of gender issues, during which the students considered the constraints placed upon the female characters in the novel, and then questioned whether or not their contemporary situation was significantly different. Some students came from cultural backgrounds where arranged marriages were or had been common in their families and spoke to that, while others discussed the objectification of women in contemporary music videos. As part of the process of negotiating with the text together, the Kenwood Academy High Teen Book Club members sometimes recognised the constructions of literary value put into circulation by ‘One Book, One Chicago’, and, at other times, they differentiated themselves from those notions. They had all read the resource guide produced by the library and were aware that the novel was a ‘classic’ but this neither troubled them, nor inspired them to read the book. They did enjoy knowing that other readers in Chicago were also picking up Pride and Prejudice, and, as one young African American woman expressed it, ‘One Book, One Chicago gives our city props’. In other words, the students identified the prestige that is still ascribed to book reading as a leisure activity in US society when they talked about the ‘props’ that the program lent to their city. These students also valued their participation in a reading community that was larger than their own book club, one that could be readily imagined and which was, at times, physically realised through the program’s events. They were not especially impressed by the canonical status of Austen’s novel, nor were their reading acts particularly guided by any notion of its aesthetic value.

The type of evaluative reading that the Kenwood students undertook is maybe more recognizable as a rhetorical activity than an act of literary criticism. The promotional rhetoric of ‘One Book, One Chicago’ certainly frames the sharing of reading as a set of communicative practices by encouraging Chicagoans to ‘gather together in discussion’. Moreover, when organizers adopt the OBOC model they are usually concerned with encouraging people to communicate with each other (more, better, across differences and spaces) through a text. The model itself can be conceptualized as one that promotes shared reading as a social practice, rather than as a cultural formation that emphasizes hermeneutics or textual interpretation as its primary outcome. Organizers of OBOC programs frequently articulate a desire for some form of social change within their locality, whether expressed as a desire to ‘build community through reading’ (as Tricia Siemens of OBOCKWC declared), to foster cross-cultural understanding, or to encourage more citizens to read books. The limits of the model in terms of realizing these desires are evident from these two case studies and from our in-depth analysis of large-scale mass reading events in Reading Beyond the Book (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo). Iterations of OBOC rarely create new readers, and cannot effect structural social change, but moments of cross-cultural dialogue can occur. We have encountered examples of public events during which a city’s racialised history has been openly challenged, even as we have witnessed others where the audience avoided discussing race relations (183-88; 239-42). Similarly, the community that OBOC programs create by bringing people together to share reading tends either to be ephemeral or a physical manifestation of existing reading communities such as book clubs. But both kinds of community realization can be socially and politically valuable since, as our own research evidences, even fleeting experiences of belonging can be emotionally powerful during an era where the existence of any kind of public sphere is increasingly rare (205-44). Meanwhile, the public recognition of reading groups at OBOC events, either by the official organizer or by the members of groups themselves, can lend cultural legitimacy to a pastime that is still frequently represented as being only for women.13

When cultural mediators like OBOC event organizers ascribe social power to shared reading, they indicate not only their own professional and personal investments in the value of reading, but also the material situation of the OBOC model within the political economies of culture in nation-states like the USA and Canada. In North America, as in the United Kingdom, successive governments of the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first century ratified neoliberal cultural policies which conflated notions of cultural and social value (Fuller and Rehberg Sedo 129-38). As the first decade of the twenty-first century progressed, cultural managers who were working for non-profit arts organizations and those operating within state-funded institutions like public library systems, were increasingly required by government agencies to account for the socially transformative elements and outcomes of their programs. If we seek to understand the values of reading in the contemporary period, then, we also need to attend to the wider discursive and structural contexts within which cultural formations of shared reading such as the OBOC model emerge. As our two brief case studies have illustrated, however, investigating the various ways in which the values of reading are constructed also depends on our ability as researchers to attend to the reading practices employed by variously skilled and specifically situated reader-consumers. At the same time, understanding the types of negotiations around the value of reading—and of sharing—fictional texts by non-academic readers must include some interrogation of the way that reading events are promoted and framed by the cultural managers who organize them. For reproducing ‘the wow factor’ is not only about offering readers an emotionally-intense experience through a series of entertaining events, it also involves the reproduction of professional, personal and social values of reading.

Danielle Fuller is a Senior Lecturer in Canadian Studies at the University of Birmingham, UK. DeNel Rehberg Sedo is a Professor in Communication Studies at Mount Saint Vincent University, Canada.

Notes

1 The findings presented in this article are part of a larger research project, Beyond the Book, an interdisciplinary, trans-national analysis of mass reading events and the contemporary meanings of reading in the UK, USA and Canada. More information is available at <http://www.beyondthebookproject.org/>.

2 No complete record of OBOC programs exists, but the Center for the Book at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. registers some that have taken place in the USA, Canada, Australia and the UK, see <http://www.read.gov/resources>. By July 2012, the US agency National Endowment for the Arts had awarded more than 1,000 grants to community programs since the launch of the Big Read initiative in 2007, and each year at least 30 percent of the grants fund new OBOC programs. We estimate, then, that there are around 300 OBOCs annually in the USA alone. See <www.neabigread.org/>.

3 OBOC began in Seattle in 1998 with ‘What if All of Seattle Read the Same Book?’ and was followed closely by ‘One Book, One Chicago’ in 2001. For a more complete history of the shared reading model, see Fuller and Rehberg Sedo19-24.

4 Sociologist Wendy Griswold defines a ‘reading class’ as a group of readers who consistently read for entertainment. They have ‘a stable set of characteristics that include its human capital (education), its economic capital (wealth, income, occupational positions), its social capital (networks of personal connections), its demographic characteristics (gender, age, religion, ethnic composition), and—the defining and non-economic characteristic—its cultural practices’ (37).

5 See Fuller and Rehberg Sedo, ‘Methods Appendix’ 259-308.

6 It is worth noting that media studies scholar Henry Jenkins first identified ‘wow’ as a complex, emotional response to popular entertainments in his book The Wow Climax: Tracing the Emotional Impact of Popular Culture. In his introduction to the book, he defines ‘wow’ as ‘the sense of wonderment, astonishment, absolute engagement’ experienced by a participant (1).

7 Online surveys were conducted in each of the 10 field sites in our study, garnering nearly 3500 responses. A copy of the questionnaire can be found at: <http://www.beyondthebook.bham.ac.uk/resources/documents.html>.

8 KWC was a pilot site for the Beyond the Book project. The quantitative and qualitative data collected there informed subsequent research in 10 other sites. More information on our research methods is available in Fuller and Rehberg Sedo 259-308.

9 Mayor Daley’s Teen Book Club is a network of funded reading programs throughout the Chicago public school system. See Borrelli for a synopsis and short historical overview.

10 Chicago Public Library produced postcard-sized evaluation cards for participants in the program and invited people to make comments about ‘One Book, One Chicago’ events and the book selection. The director of the Fall 2005 program, Nan Alleman, kindly allowed us to see these cards.

11 Quotations from responses on library evaluation cards.

12 Anonymous respondent to our own online questionnaire, October 2005.

13 For an explicit example, see Fuller and Rehberg Sedo 179-80.

Works Cited

Alleman, Nanette. Personal interview. 5 January 2004.

Alvarez, Julia. In the Time of Butterflies. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994.

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. London: T. Egerton, 1813.

Beckett, Lois. ‘America’s Most Outrageous Teacher Cheating Scandals.’ ProPublica. 1 Apr. 2013. <http://www.propublica.org/article/americas-most-outrageous-teacher-cheating-scandals>.11 Mar. 2014.

Borrelli, Christopher. ‘Daley’s Last One for the Books.’ Chicago Tribune 2 Mar. 2011. <http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2011-03-02/entertainment/chi-mayor-daley-one-book-20110302_1_book-discussions-citywide-book-club-mary-dempsey>.18 Mar. 2014.

Caretta, Angela. Personal inverview. 10 November 2004.

Casey, Allan. Lakeland: Ballad of a Freshwater Country. Vancouver, BC: Greystone Books/David Suzuki Foundation, 2011.

Chicago Public Library. ‘One Book, One Chicago—Pride and Prejudice—Introduction.’ One Book, One Chicago 2005. <http://old.chipublib.org/eventsprog/programs/oboc/05f_prideprejudice/oboc_05f_intro.php>. 18 Mar. 2014.

de la Torre, Marissa, and Julia Gwynee. When Schools Close: Effects on Displaced Students in Chicago Public Schools. Chicago: Constortium on Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago Urban Education Institute. <http://ccsr.uchicago.edu/publications/when-schools-close-effects-displaced-students-chicago-public-schools>. 11 Mar. 2014.

Dybek, Stuart. The Coast of Chicago. New York: Macmillan, 2004.

Fowler, Karen Joy. The Jane Austen Book Club. New York: Putnam, 2004.

Freedman, Douglas. ‘Chicago Residents Fight Public Schools Closures.’ Liberation. 3 Mar. 2009. <http://www2.pslweb.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle &id=11473&news_iv_ctrl=1221>. 11 Mar. 2014.

Fuller, Danielle. ‘Prolegomenon: Reader at Work.’ Trans/Acting Culture, Writing, and Memory: Essays in Honour of Barbara Godard. Ed. Eva C. Karpinski, Jennifer Henderson, Ian Sowton and Ray Ellenwood. Waterloo, Ont. Wilfrid Laurier U P, 2013. 1-20.

Fuller, Danielle, and Rehberg Sedo, DeNel. Reading Beyond the Book: The Social Practices of Contemporary Literary Culture. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Gabriel, Trip. ‘Cheat Sheet—Under Pressure, Educators Tamper With Test Scores.’ The New York Times 10 June 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/11/education/11cheat.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0>. 11 Mar. 2014.

Godard, Barbara. ‘Feminist Speculations on Value: Culture in an Age of Downsizing.’ Ghosts in the Machine: Women and Cultural Policy in Canada and Australia. Ed. Alison Beale and Annette Van den Bosch. Toronto: Garamond, 1998. 43-76.

—. ‘Privatizing the Public: Notes from the Ontario Culture Wars.’ Fuse 22.3 (1999): 27-33.

—. ‘Upping the Anti: Of Poetic Ironies, Propaganda Machines and the Claims for Public Sponsorship of Culture.’ Fuse 24-25.3 (2001): 12-9.

Greeno, Cherri. ‘Special Honour for Author: Novel Selected for Region’s One Book Program.’ The Record 23 Apr. 2004: A1.

Griswold, Wendy. Regionalism and the Reading Class. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2008.

Hall, Stuart. ‘The Neoliberal Revolution.’ Soundings: The Neoliberal Crisis. Ed. Jonathan Rutherford and Sally Davison. London: Lawrence Wishart, 2012. 8-26.

Jenkins, Henry. The Wow Climax: Tracing the Emotional Impact of Popular Culture. New York: New York University Press, 2007.

Jernigan, Kim. Personal interview. 10 November 2004.

Lee, Harper. To Kill a Mockingbird. New York: J.P. Lippincott & Co., 1960.

Levy, Andrea. Small Island. Place of publication not identified: Headline Review, 2007.

MacLeod, Alistair. No Great Mischief. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999.

Murray, Simone. The Adaptation Industry: The Cultural Economy of Contemporary Literary Adaptation. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Penney, Louise. Bury Your Dead. London: Sphere, 2010.

Report of the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters, and Sciences 1949-1951. Ottawa, Ont.: Government of Canada, 1951. <https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/massey/h5-400-e.html>. 17 Mar. 2014.

Ricci, Nino. Lives of the Saints. Toronto: Cormorant Books, 1990.

Sawyer, Robert J. Hominids. Toronto: TorBooks, 2002.

Siemens, Tricia. Personal interview. 3 July 2003.

—. Personal interview. 10 Nov. 2004.

Smith, Alisa, and J.B. MacKinnon. The 100-Mile Diet: A Year of Local Eating. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2007.

Smith, Sharron. Personal interview. 3 July 2003.

Smith, Sharron, and Maureen O’Connor. Canadian Fiction: A Guide to Reading Interests. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2005.

Statistics Canada. ‘Census Profile.’ <http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm?HPA>. 17 Mar. 2014.

Statistics Canada. ‘2006 Census: Education (including Educational Attainment).’ <http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/rt-td/edct-eng.cfm>. 17 Mar. 2014.

Taylor, Joan Bessman. ‘Good for What? Non-Appeal, Discussibility, and Book Groups (Part2).’ Reference & User Services Quarterly 47.1 (2007): 26-31.

—. ‘Readers’ Advisory—Good for What?’ Reference & User Services Quarterly 46.4 (2007): 33.

Travis, Trysh. ‘Divine Secrets of the Cultural Studies Sisterhood: Women Reading Rebecca Wells.’ American Literary History 15.1 (2003): 134-61.

Urquhart, Jane. The Stone Carvers. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2001.

United States Census Bureau. ‘Chicago (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau.’ State & County QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau, n.d. 18 Mar. 2014.

Wright, David. ‘Mediating Production and Consumption: Cultural Capital and “Cultural Workers”.’ British Journal of Sociology 56.1 (2005): 106-21.