By Melinda Harvey and Julieanne Lamond

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version.

This essay presents and analyses the initial results of a large-scale and comparative quantitative survey of book reviews to draw some conclusions about the current state of Australian book reviewing as a field. We argue that the gender disparity in Australian book reviewing that has been identified by the Stella Count over the past four years needs to be seen in the wider context of changes to the nature and extent of book reviews over time. We compare two key publications across two years, three decades apart: Australian Book Review (ABR) and The Australian in 1985 and 2013.

This study is motivated by an interest in the interrelationship between forms of writing about literature that take place within and beyond the academy. Book reviewing is an understudied sector of the literary field, despite the fact that it has an influence on authors’ careers, book sales and publishers’ commissions as well as on the determinations of literary value that underlie the discipline of Literary Studies. In this paper, we use ‘literary journalism’ to broadly describe writing about literature published in non-academic outlets in the print and online media, of which book reviews are a subset. We use ‘academic literary criticism’ to describe writing about literature which is published in scholarly journals and monographs.

Our study finds a situation in which the allocation of space within the books pages of The Australian and ABR is shifting: the number of books being reviewed has dramatically decreased across both publications, and the proportion of feature reviews has substantially increased. We find that the ubiquitous red-and-blue pie charts produced by feminist literary organisations Stella and VIDA, with their focus on percentage and not scale, underestimate the implications of the gender bias they identify. When we compare The Australian and ABR in 1985 to 2013 we can see that changes in the size and shape of the book reviewing field, as well as to review type and length, have compounded the disparity identified by repeated attempts to quantify it.

I. Background to our study

Discussion about book reviewing in Australia—as elsewhere—has usually taken place outside the academy. There is only one academic monograph on book reviewing: Gail Pool’s Faint Praise: The Plight of Book Reviewing in America (2007). Prior to that, scholars were critic-focused and did not survey book reviewing as a form or a field: for example, George Watson’s The Literary Critics: A Study in Descriptive Criticism (1962) and, more recently, James Ley’s The Critic in the Modern World (2014). This does not accurately reflect the centrality of book reviews to academic literary criticism. Book reviews are often the first port of call for researchers keen to ascertain the reception of a particular book or the socio-historical context in which it was produced. Indeed, academics working in Literary Studies blithely quote from book reviews as evidence but rarely acknowledge or question what Simon During would call their ‘institutionality’ or even their historicity—that is, the set of institutions within which book reviews are produced, and the historical, social, economic and geographical contexts of the periodicals in which they are published (During 317; Dale and Thomson 124).

In the Australian context, there is a significant body of research into nineteenth-century literary journalism, which has tended to use book reviews to trace the development of a national literature (Dale and Thomson 120). In addition, there have been two studies looking explicitly at book reviewing in Australia: in 1930 (Dale and Thomson) and five years, a decade apart, from 1948 to 1978 (McLaren). This has not been matched by a similar interest in the book review’s relation to contemporary literature. There have been several missed opportunities: only brief mention is made in Peter Pierce’s and Elizabeth Webby’s important books surveying Australian literature published by Cambridge University Press; Craig Munro and Robyn Sheahan-Bright’s Paper Empires: A History of the Book in Australia, 1946-2005 has chapters on festivals and writers’ centres but not book reviewing. Exceptions to this are Katherine Bode’s Reading by Numbers and ‘Methods and Canons: An Interdisciplinary Excursion’, in which she examines newspaper mentions of Australian writers as recorded in the Austlit database in the context of academic discussions of these writers, publication statistics and the gendering of the literary field. However, her data does not distinguish between reviews and other forms of literary journalism, and only includes a fraction of the book reviewing taking place in Australia in this period. Austlit’s indexing of newspaper reviews of Australian writers is far from comprehensive, and largely excludes two very prominent components of the book pages in Australia: reviews of nonfiction books and works by overseas authors. These aspects need to be examined in order to understand the field of book reviewing. There has also been some interest in book reviewing outside of the field of Literary Studies, notably from media scholars Sybil Nolan and Matthew Ricketson’s ‘Parallel Fates: Structural Challenges in Newspaper Publishing and their Consequences for the Book Industry’, which examines copy-sharing in the Fairfax newspapers.

There are a number of reasons for the academic neglect of the field of contemporary book reviewing: these include the scale and diversity of book reviews; the precariousness of outlets and their contents; as well as the embeddedness of book reviews in the economics of publishing and the print media. Literary Studies’ ongoing project to legitimate itself as a discipline systematic or ‘scientific’ enough to belong inside the university has also played a part. In his book Professing Literature, Gerald Graff has argued that scholars actively and consciously ‘wanted to purge’ Literary Studies of ‘sentimentality and amateurism’ (121-2); literary journalism has provided it with a convenient foil. Academic criticism has, at various times, rejected approaches frequently seen in book reviewing: biographical criticism; jargon-free language; affective criticism; and—with the embrace of Theory and, more recently, Big Data—close reading.

There are, however, a number of justifications for the study of book reviews by academics, and especially in the Australian context. To begin with, book reviews form part of the history of the book in Australia. Literary journalism has been, for periods of time, the dominant mode of consideration of Australian literature. Until the institutionalisation of Australian Literature as a discipline in the academy from the mid-1950s, it was public critics, not academics, who were responsible for describing and evaluating the national literature. This critical interest in Australian literature outside academia continues to be influential—more influential, in fact, that most work produced from within. Veronica Brady and Christopher Lee as well as David Carter have noted that ‘[o]utside the universities there are prominent independent critics’ who have ‘a more direct influence than academic critics on publishers, readers and editors’ (Carter 258; Brady and Lee 278). The justifications mounted by Michael Heyward for Text Publishing’s Australian Classics series—which coincided with the publication of Geordie Williamson’s The Burning Library and the ‘Australian Literature 101’ series of public talks at the Wheeler Centre[1]—were predicated on what we contend is the false assumption that academics have neglected Australian literature in their research and teaching (Dunn). A generous interpretation of this charge is that Literary Studies academics find it difficult to get their research into the public sphere due to, for example, the cost of access to academic publications and conferences. These difficulties are compounded by the institutional disincentives academics face—such as the ERA national research evaluation framework and internal publication rankings—when they want to engage in public acts of criticism such as book reviewing.

Another reason book reviewing requires scholarly attention is that new literature continues to be given its first critical scrutiny in book reviews. This means that reviewers play an important role in setting the agenda in terms of the way an individual text is engaged with and understood. At one time, the academic study of literature was retrospective and historical. Graff has shown that it took a long time for the teaching and research of contemporary literature not to be dismissed as merely ‘impressionistic’ and ‘subjective’ (136-7). Meanwhile, the job of the book reviewer, as Virginia Woolf explained it in her 1939 essay ‘Reviewing’, has always been to ‘t[a]k[e] the measure of new books as they f[a]ll from the press’ (119). Book reviews are instrumental in determining a text’s literary value. A fundamental expectation of book reviews by readers, writers and critics alike is that they answer the question, ‘Is the book any good or not?’ (Pool, Faint Praise 11; Bishop; Goldsworthy 21). As Pool has argued, this evaluative role is important because it ‘build[s] careers and reputations’ (Faint Praise 9). Book reviews are used—and indeed written—by the people who sit on prize committees, program literary festivals, order for libraries and bookstores, and commission for publication. These are activities that have an impact on sales and also promulgate literary value. Academic Literary Studies is, whether it likes it or not, also involved in evaluative acts. Propounding and protecting and, more recently, interrogating and extending the canon are functions of Literary Studies as a discipline. Despite the decanonising impulse underlying many approaches in Literary Studies over the past four decades, academics inevitably continue to exercise literary judgement by designing syllabuses as well as choosing research topics for conference papers, publications and grant applications. As Robert J. Meyer-Lee argues, ‘an inherited commitment to literary value remains concealed within critical and textual approaches that otherwise disclaim or simply ignore it’ (336). He notes that recent studies into the question of literary value tend to

a priori eliminate consideration of a vast array of manners in which literature has been, in fact, valued, especially outside the research domain of the academy. For, regardless of what the nature of literary value may be, literature has always been valued by diverse agents for diverse reasons. (339)

The important point here is that these various ‘acts of valuing’ do not take place independently of one another: Meyer-Lee argues that literary value is best understood in terms of the complicated networks of acts of valuing that constitute it, including those that take place beyond the academy in the pages of the print and, increasingly, online media. The explicit evaluation taking place in book reviews is imbricated in the much more implicit evaluation that forms part of the daily work of Literary Studies academics.

II. Quantifying the field of book reviewing

The field of book reviewing is difficult to quantify as a whole, much less to track changes over time. The challenges it presents are manifold, but two are key. Firstly, there is a problem of its diversity. Reviewing takes place across a range of publication types—from broadsheet- and tabloid-formatted national, metropolitan and regional newspapers, to specialist journals and magazines. In addition to these there are amateur ‘born digital’ book reviews such as appear on online platforms such as Goodreads, LibraryThing and Amazon, as well as the burgeoning fields of book blogging and BookTubing (see for example Murray). Then there are semi-professional sites like The Newtown Review of Books that offer edited content but do not pay their writers. Second, and arguably most importantly, there is a problem of scale. There were more than 3,500 books reviewed in Australian publications in 2015.[2] The time and money it takes to produce a dataset from a pool of this size is significant—much more than an individual academic working to a publications target set by her home institution can justify. It is work best done in collaboration: another problem for Literary Studies academics, who have traditionally worked alone. Money also helps: the laborious manual collection, although it requires attentiveness, need not be done by the researchers themselves and might be completed by paid research assistants.[3] But it is difficult for Literary Studies academics to access such support as they have struggled to attract Australian Research Council grants[4] and their linkage opportunities are hamstrung by the fact that their most likely industry partners are, likewise, cash-strapped and under-resourced.

It has fallen to feminist literary organisations VIDA: Women in Literary Arts in the United States and The Stella Prize in Australia to compile statistics on specific aspects of book reviewing across a range of publications. VIDA has been counting 39 of what they call ‘Tier 1’ publications in the U.S. and U.K., with the aim of verifying gender disparity in terms of reviewers and authors reviewed since 2010. For six years now they have been producing their now trademark blue and red pie charts that have consistently shown a ‘sloped playing field’ as far as men and women’s representation in ‘the pages of venues that are known to further one’s career’ is concerned. The most prestigious publications, the London Review of Books and The New York Review of Books amongst them, have proven to be the least equitable and the least likely to show even minor shifts or fluctuations (VIDA). The Stella Prize, in part inspired by VIDA and incensed by the conditions that led to 2009 and 2011’s ‘sausage-fest’ shortlists for the Miles Franklin Literary Award, began its counting of book reviews in 2012. This Count has formed part of a broader program of feminist literary activism that includes a women’s-only annual literary prize worth $50,000 and curriculum intervention in secondary schools. The 2012 Count included only the gender of authors of books reviewed. In 2013, this expanded to include the gender of reviewers. Since 2014, we have been collaborating with the Stella Prize to produce the statistics for the Count. For 2014, we expanded the scope of the count to include review size and genre of books reviewed. The 2015 Stella Count has also included reviewer occupation. Our aim in working with the Stella Count is to produce the most detailed set of statistics about a nation’s contemporary reviewing culture to date.

The statistics produced by both VIDA and Stella have triggered voluminous commentary, much of it critical of the publications involved and in favour of change. Gender bias in the book reviewing field was treated as news, but counts of this type are not new, neither overseas nor here in Australia. Nor are the kind of excuses trotted out for the disparity: that women pitch less and say no more than men and that the bias is an unconscious and unintended result of the fact that men write more of the books sent out by publishers for review or that are of potential interest to publication’s readers (Case; Caplan and Palko 16). Studies of this kind have their momentary time in the sun and are then forgotten, and this seems to be part of a larger cycle that identifies women’s disadvantage and then forgets that it exists, with no real change having been effected. As Pool says, the publishing industry isn’t good at remembering these battles, however high-profile they have been (‘Book Reviewing’ 10), but reminding industry and activist players that there has been a history of such battles is a way that academics can usefully intervene in the field.

Past counts—in Australia and overseas—range from the small and ad hoc to the large and totalising. Mark Davis in his 1997 book Gangland, for example, reports gender inequality, on top of an entrenched generational divide, in a somewhat extemporised survey of a four-week period in The Australian from 21 October 1995 to 11 December 1995:

In the first week the reviews kicked off with a feature review of an autobiography by a male writer, accompanied by a review of some male childhood reminiscences. The following week the book pages were dominated by three feature reviews of biographies of prominent men. The next week these same pages opened with another feature review of a biography of a prominent man. Inside were two long reviews, one of a biography of a prominent man and another of an autobiography of a prominent man. The following week’s pages also opened with a full-page feature review of a biography of a prominent man. Most of the reviews over a two-month period were also by middle-aged men, the overwhelming majority reviewing books by men. If feature reviews alone are counted, the pro-male bias is much higher. (127-8)

Other counts have been more complete. For example, in 2004 Paula J. Caplan and Mary Ann Palko tallied 53 consecutive weeks of the New York Times Book Review, the largest outlet in the U.S., from 2002 to 2003 and found that

more than twice as many book authors and almost twice as many reviewers were male as female. Specifically, out of 807 books reviewed only 227, or 28%, were authored by women. Of the 775 reviews only 265, or 34%, were by women reviewers.

In their report they note that a similar count of the New York Times Book Review had taken place previously in the 1980s ‘after Marilyn French and approximately 100 other women writers protested the three-to-one, male-to-female ratio for authors and reviewers’ (16). There have been a number of other counts besides: for example, by D. H. and C. M. Noble of 12 U.K.-based newspapers from 1 October to 21 December 1973 (Noble) and Pool of the New York Times Book Review, New York Review of Books, The New Republic and BookForum in 2006-2007 (‘Book Reviewing’ 9).

The most complete count that has been conducted to date was by the U.K.-based organisation, Women in Publishing, which was established in March 1979 by Anne McDermid, Liz Calder and the two co-founders of Virago Press, Ursula Owen and Australian Carmen Callil ‘to promote the status of women working in publishing and related trades’. At a June 1985 meeting, it was decided that the organisation would produce a systematic survey of the national book reviewing field over a period of one year ‘to find out whether there was bias and, if so, to what extent’ (Women in Publishing 1-2). They counted 28 publications across the spectrum of ‘highbrow to popular’, looking at 12 issues per publication in 1985. The result was a study examining 5,018 reviews for the length and prominence of review and the genre and publisher of the books reviewed (6). Their results were published in a book called Reviewing the Reviews: A Woman’s Place on the Book Page (1987). In short, they found that ‘whether [publications] are to the left or right of the political spectrum, a quality Sunday newspaper or a literary magazine, devoted to humour or education, their book sections are concerned mainly with reviewing books by men’ (10). This forgotten study has been instrumental to our thinking about the data collection for our project.

While it might seem strange that the majority of the comprehensive data on book reviewing has been carried out by feminists outside of the academy, this reflects the different imperatives of activist and academic statistical collection. In the context of feminist activism, detailed statistics speak to problems in a way that more indicative or anecdotal accounts do not. Explaining her decision to initiate the VIDA Count with co-founder Cate Marvin back in 2009, Erin Belieu has argued that those who encounter gender bias often face accusations that they are ‘misreading’ the situation and that the VIDA Count gives these people ‘a powerful political voice, actual data to point to, and a rallying point’: ‘We at VIDA aren’t big fans of anecdote. Anecdote is too easy to dismiss’ (117). Anecdote is on the level of the particular occurrence; data is collective. Anecdote is coloured by the individual who tells it; data has the hardness of fact. While data might provide proof, it has not brought about real change. Pool, writing in 2008, noted:

I wrote an article on sexism in magazines back in the eighties and diligently counted names of women on mastheads (no higher math involved). I could not have imagined that I would still be counting twenty years later. I question whether such tallies are effective. Clearly, to show that a disparity exists, we need the evidence the numbers provide. But numbers don’t tell the whole story. (‘Book Reviewing’ 9)

We agree with Pool: numbers do not tell the whole story. The whole story requires an understanding of literary and media history. We also note that data is not objective: it is another form of argument, and the product of decisions about what to count and in what terms. As Bode and Murphy note, data is ‘an outcome of multiple decisions, and based on arguments, not certainties, regarding degrees of bias, reliability, and purpose’ (177). However, collecting this kind of data provides opportunities for much thicker descriptions of the field of book reviewing. This paper is just a beginning.

III. Our study

This paper begins to extend the comprehensive counting of reviews to include aspects of the book reviewing field that are not limited to gender. For this paper, we collected detailed statistics on book reviews published in The Australian and ABR for the full years of 1985 and 2013.[5] In creating our data we counted each review as either a capsule, a composite or a feature. The feature review takes a single book as its subject and tends to be between 600 and 1000 words. A capsule review is generally less than 400 words and is usually grouped together with other short reviews, often written by the same people across issues. A composite review considers several books inside a single review. For each review, we recorded information including: the date and title of the review, the author, title, genre and publisher of the book reviewed, the reviewer’s name, gender and occupation (where available), and the length and prominence of the review. This data includes 2,308 instances of book reviewing across 21 fields in Australia in 1985 and 2013, amounting to more than 48,000 cells of data.

The statistics reported here refer to books reviewed because we chose to count each instance of a book being reviewed in order to be specific about the number of both the individual titles and book authors being reviewed. In other words, composite reviews have been counted for each book reviewed. We also make a distinction between books reviewed and individual titles reviewed. This is necessary because individual books are sometimes reviewed more than once in the same publication in the same year. There are limitations to our data: we have not counted reviews of children’s or Young Adult books, nor do we include extracts from books or feature articles on and interviews with authors. Regarding children’s books, we recognise that their omission means that our statistics do not include a significant part of the field. In the case of extracts, feature articles and interviews, we acknowledge that their increasing prominence in the book pages between 1985 and 2013 deserves analysis. Anecdotally, we can report that there does seem to be a patterned relationship between these parts of the book pages and the feature reviews. Certainly, these modes of literary journalism are also involved in similar evaluative acts as the reviews that sit beside them in the printed newspaper and magazine.

We chose to begin our collection of statistics across a range of periodicals with The Australian and ABR because they (1) are national publications; (2) offer the largest coverage of books in the Australian context; (3) have high visibility; (4) have large circulations; and (5) are, arguably, two of the most prestigious sites for reviews in the country. Regarding prestige, ABR receives more funding from the Australia Council than any other literary magazine, in recognition ‘for [its] national leadership in artistic excellence and the critical role [it] plays in the Australian arts landscape’. In a climate of cuts, ABR secured four-year funding to the tune of $560,000 (Australia Council). It is also supported by two universities, Monash and Flinders, and attracts significant private philanthropy, including from high-profile writers, judges and QCs, and Order of Australia recipients. ABR estimates its combined readership to be over 50,000 and its website hits at over 175,000 per year (ABR).

As for The Australian, its prestige in the field accrues as a result of its circulation numbers, comprehensiveness, regularity and pay rates, which at 70 cents per word for reviews is amongst the highest in the country. If it is still true that the Saturday book pages ‘are the writing and publishing world’s public face’, as Davis asserts in Gangland, then it is in The Australian that we come closest to meeting it (127). We acknowledge that the prestige of these publications is not, perhaps, consistent over the period 1985 to 2013; the proliferation, and diffusion, of venues for book reviewing, especially online, has made inroads. But this, in itself, offers yet another reason to track the changes to the book reviewing field over time. There is one final reason we have chosen these specific publications: The Australian and ABR are rare examples of continuity in what Nettie Palmer once called ‘the inconsecutive nature of our literary life in Australia’ (xxxi).[6] Since 1985, numerous publications printing book reviews such as the National Review, National Times, Australian Literary Review (twice) and Scripsi have come and gone. Other periodicals—amongst them Meanjin, the latter expressly founded by Clem Christesen to produce ‘a core of sound literary criticism’ (Cunningham 16; Carter 270)—ceased including book reviews in their issues.

One of the reasons we have chosen 1985 as our comparison year for 2013 is because of the potential it offers for transnational analysis alongside the Women in Publishing study. The mid-1980s also represents a moment in Australian literary history worth studying in its own right. In Reading By Numbers, Bode identifies this as a high-water mark in Australian women’s publishing; ‘in the 1980s,’ she writes, ‘Australian women novelists were increasingly present on the lists of local literary presses and considerably more likely to receive critical attention than at any other time since the end of the Second World War’ (148). Our study tests some of Bode’s speculations about the shifts in the gendering of critical authority in this period of Australian literary history.

Part of the motivation for this particular study has been to track book reviewing over time. Past instances of counting have tended to be localised and isolated. Despite the fact that the VIDA and Stella Counts have now been running for six and four years respectively, it will be a long time before we can verify that the slight fluctuations in gender disparity across publications they are identifying from year to year constitute anything like real changes to the field as far as gender is concerned. A 1985 dataset means we have the measure by which change across a number of different features can be proven. The time gap also allows us to track the consequences of the seismic shifts in the book reviewing space brought about as a consequence of the transformations newspapers and magazines are grappling with due to the digital revolution.

IV. Gender

In her study of trends in the publication and discussion of Australian writers, Bode finds that

the progressive and broad-ranging growth in women’s authorship of Australian novels since the 1970s was accompanied, in the 1990s and 2000s, by a reversion—in this most public and widely read forum for discussion of Australian literature [newspapers]—to a focus on men. (162)

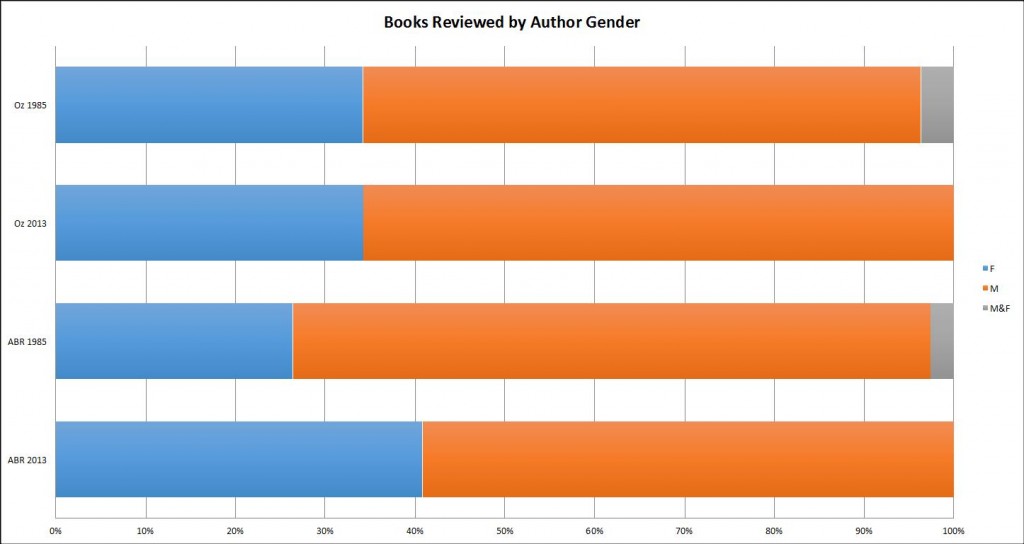

Our study of Australian book reviewing has not found a resurgence of interest in male authors, but rather a continuity in the relative lack of interest in books by women in the reviews pages of The Australian and ABR in 1985 and 2013. Bode’s data indicates that in 1985 40% of the top 20 Australian authors mentioned in Australian newspapers were women (Austlit). Our data indicates that rates of reviewing of women’s writing were lower than this in 1985, and continue to be so. In these publications, books authored by women were significantly less likely to be reviewed than books authored by men in both 1985 and 2013 [Figure 1].

Figure 1: Books Reviewed by Author Gender

Books written by women constituted 33% of books reviewed in The Australian in 1985 and 34% in 2013. In the Stella Counts of 2014 and 2015 the percentages of books by women reviewed in The Australian were 31% and 36% respectively. In ABR, the percentage of books reviewed that were authored by women has increased from 26% in 1985 to 41% in 2013, then back to 38% and 34% in 2014 and 2015.

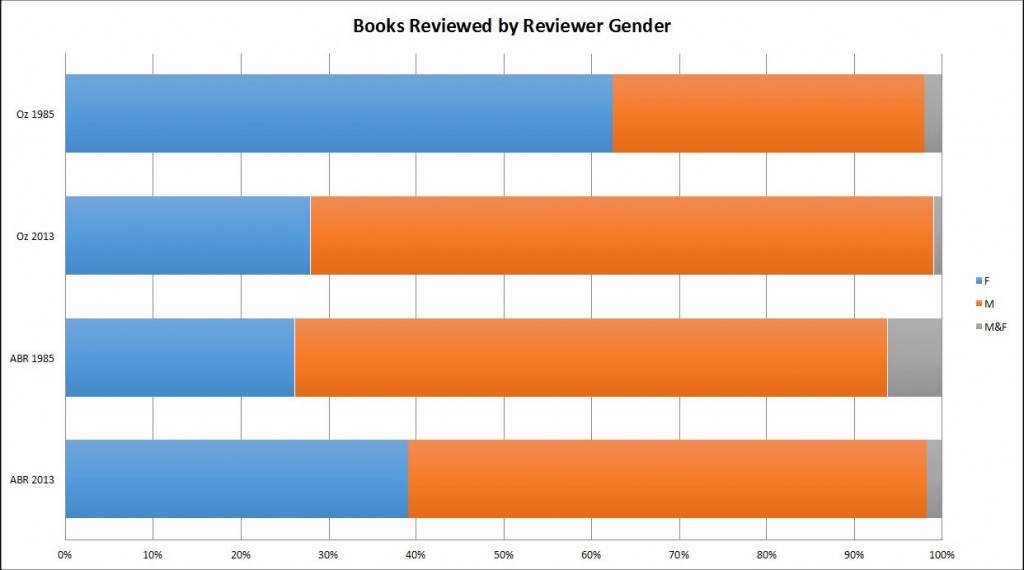

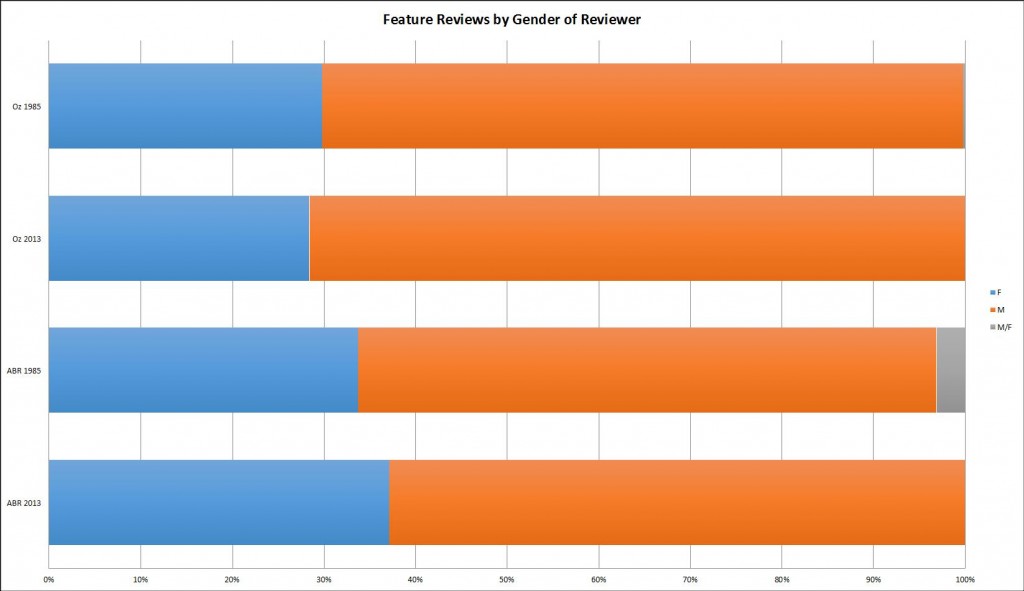

Bode wonders whether men ‘dominate[…] the reviewing of Australian novels: whether they stand as arbiters as well as the exemplars of cultural value in the contemporary field’ (167). According to our dataset, the answer to this is: yes. In ABR, the majority of book reviews were and continue to be, written by men, although there has been some shifting of the ground: women reviewed 26% of books in 1985 and 39% in 2013. There is an even more interesting story to tell about gender in The Australian. To our surprise, women reviewed 62% of all books in The Australian in 1985 [Figure 2].

Figure 2: Books Reviewed by Reviewer Gender

When we looked more closely at the data, we discovered that, of the 639 books reviewed in The Australian in 1985, 468 were capsule reviews written by two women: Sandra Hall, then literary editor of The Australian, and Vicki Wright, who was responsible for the regular ‘Paperbacks Worth Having’ column in the paper. We discuss what we are calling the ‘Hall-Wright Effect’ in further detail below, but note that for feature and composite reviews in The Australian in 1985 the gender split is very similar to that of ABR: that is, women reviewers are responsible for only 32% of the books reviewed compared with 68% men. In The Australian in 2013 even fewer books are reviewed by women. Including Hall and Wright, the percentage of books reviewed by women in The Australian has dropped from 62% to 28%. Excluding Hall and Wright, it has dropped from 32% to 28%. This shift seems to be continuing: in the 2015 Stella Count, 26% of books in The Australian were reviewed by women.

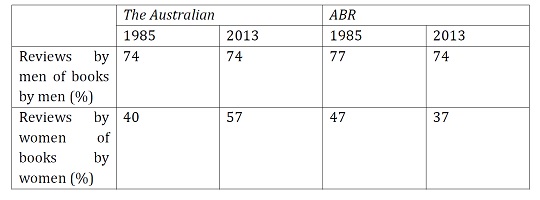

We also found that men overwhelmingly review books written by men. In The Australian in 1985, 74% of all book reviews written by men were of books by men; this statistic did not change in 2013, and the numbers are very similar at ABR. Women, however, review books by both men and women [Figure 3].

Figure 3: Book Author Gender by Gender of Reviewer

Bode describes an ‘essentialist model of cultural production and consumption’ in which it is assumed that ‘only a male author would interest a male audience, while only a female author would interest—and deign to write for—female readers’ (137). Our statistics confirm this essentialism at work in relation to male reviewers, but suggest that it is also compounded by a form of male universalism, which assumes that books by men are for everybody but books by women are only for women.

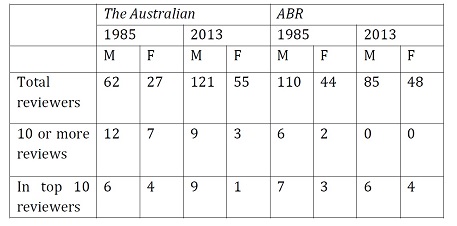

We also scrutinised the reviewer statistics more closely to investigate the size of the reviewing pool by gender. The pool of individual reviewers at The Australian has increased over time but in both 1985 and 2013 the pool of male reviewers was more than twice the size of that of female reviewers [Figure 4]. A constituent of critical authority is regularity of output in a single outlet; the reviewer accrues influence thanks to an association with a respected masthead. These numbers suggest that there are significant impediments to women reviewers developing this kind of authority, especially recently: in 1985 in The Australian, there were four women in the top ten reviewers by number of books reviewed; in 2013, this had dropped to one woman in the top ten. There were significantly more women writing ten or more reviews each in 1985 than in 2013. In 2013, the highest number of reviews produced by a man reviewer was 30; by a woman it was 13.

Figure 4: Individual Reviewers

ABR has had a larger pool of reviewers across the period, which is unsurprising given the breadth of subject matter covered in the magazine, especially in its nonfiction reviews. The representation of women in the top ten reviewers in ABR is much higher than in The Australian but remains at a glass ceiling of three in 1985 and four in 2013. ABR has clearly increased its pool of women reviewers, and across the board repeat reviews are less likely. We might conclude from these figures that the book reviewing in 2013 is more polyvocal, which is arguably a good thing for the field. However, it is a bad thing for the professional reviewer, whose reputation depends upon repeat reviewing. Commentators talk about the decline of the public intellectual: perhaps changes in the field—which coincide with the demise of the Pascall Prize’s Australian Critic of the Year award after 27 years—mean she can no longer exist.

V. The shape and size of the field

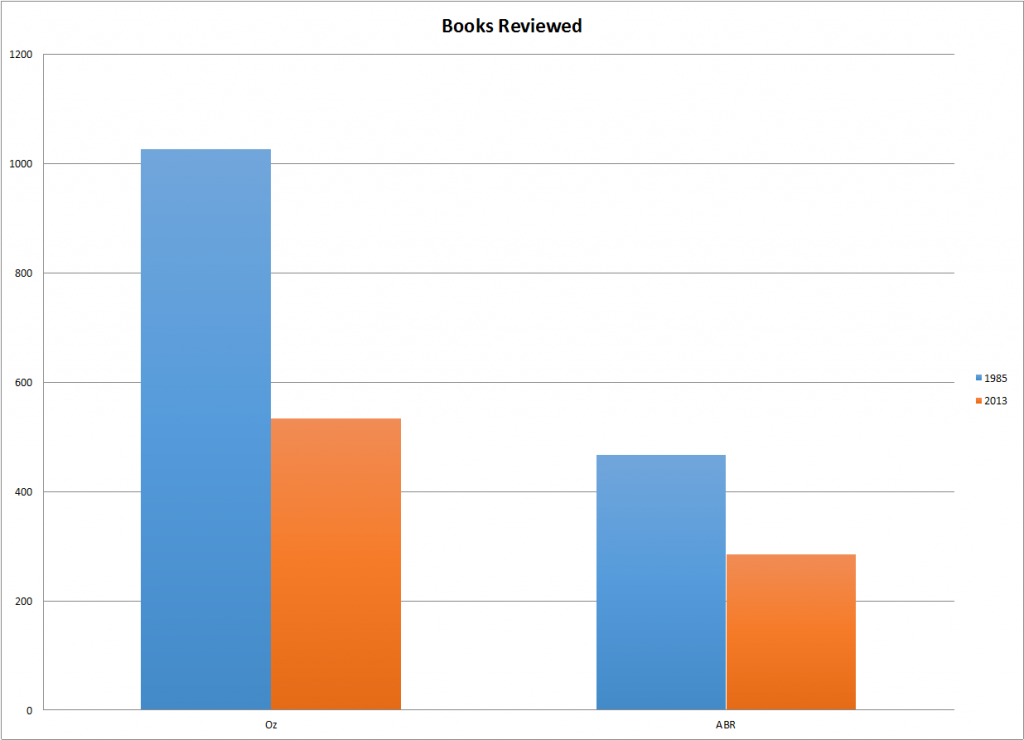

Upon first glance, the space allocated to books in The Australian increased from two to seven pages between 1985 and 2013. This would seem to support Nolan and Ricketson’s findings that in the first decade of the 21st century ‘[l]iterary pages actually increased in a number of newspapers, including The Age, The Weekend Australian, and the Canberra Times’ (Nolan and Ricketson). Despite the increasing page space, there was, in fact, a dramatic drop in the number of books being reviewed between 1985 and 2013 [Figure 5]. The number of books reviewed in The Australian dropped by 48% between 1985 and 2013, from 1025 to 533. In ABR we find a comparable increase in page space (issues ran up to 45 pages in 1985 compared to up to 71 pages in 2013) and drop in the number of books being reviewed of 39%, from 466 to 284.

Figure 5: Books Reviewed

This discrepancy between page space and the number of books reviewed can be explained, firstly, by changes in layout and design. In 1985, The Australian’s book pages were printed as a standalone tabloid-formatted supplement. Compared with the 2013 book pages—which now appear in an arts supplement called ‘Review’, consisting of a combination of music, visual arts, film and television coverage and op. ed. pieces—the 1985 books pages are much harder on the eye: there is less white space, and the font size and line spacing is smaller. But the discrepancy can also be explained by increases in advertising space as well as the number of feature articles, essays, interviews and excerpts published.

The decreasing scope and increasing length of Australian book reviews reflect a shift away from reportage and towards opinion and analysis in Australian news media over the past fifty years. McLaren identifies a shift of emphasis towards editorials and feature articles taking place in the 1960s; this has only increased over the three decades since 1981, when he was writing (McLaren 245). In the specific case of ABR, this shift can be explained by modifications to its remit since its inception in 1978. ABR began its life with a policy of ‘noticing every Australian book published’. The challenge of this endeavour quickly became apparent so the policy shifted in 1979 to noticing ‘all imaginative writing—poetry, drama and fiction—by a review matched in length to the importance of the book, and to notice all other books initially with a short notice’ (McLaren 250). ABR has since broadened its potential scope by reviewing books by international authors but this has not resulted in an increase in the total number of books reviewed. In 1985 ABR published 451 reviews of books by Australian authors and 14 from overseas; in 2013 there were 196 reviews of books by Australian authors and 87 from overseas. In other words, ABR devoted 97% of its reviews in 1985 to books by Australian authors. That number dropped to 69% in 2013. When you consider that the overall number of reviews published has fallen by 39%, this is a staggering decrease in ABR’s scrutiny of new books by Australian authors.

The shrinkage in the number of books reviewed indicated by our statistics is not unique to The Australian and ABR. Sybil Nolan and Matthew Ricketson’s study of copy-sharing across Australian newspapers reveals both a reduction in the page space allocated to book reporting and reviews in the Fairfax papers, and an increase in the practice of copy-sharing, which sees reviews reprinted across newspapers run by the same company. This results in fewer books being reviewed and less diversity of published opinion for the ones that are reviewed. They cite The Age’s Literary Editor, Jason Steger, who confirms: ‘it’s fair to say we are no longer scrutinising as many as we have in the past. And because we are increasingly sharing reviews, it means that we do not have as many critical voices as we used to’ (Nolan and Ricketson).

The shrinkage of the book reviewing field we, and others, observe is significant when you take into account the number of books published in Australia each year. Some 28,234 books were published in Australia in 2013 (Coronel 4). According to the Stella Count, 3,883 books were reviewed in Australia in 2013. That is only a 14% chance of landing an Australian-based review. Going by the Stella Count statistics for 2014 and 2015, the total number of reviews published in Australia is dropping by 150 each year, meaning that the chance of landing an Australian-based review is decreasing by a rate of around 5%.[7] More than 7,000 of the books published in Australia in 2013 were by Australian authors (Coronel 4). The sum total of books reviewed in The Australian and ABR for 2013 is 817. If, as our ABR statistics indicate, roughly half of these are by Australian authors, then 6% of Australian books are reviewed in either of these publications. We acknowledge that not all books need reviewing and that some books need reviewing more than others. That said, many Australian books go missing in this step in the chain from author to reader—especially those written by women.

VI. Review type and length

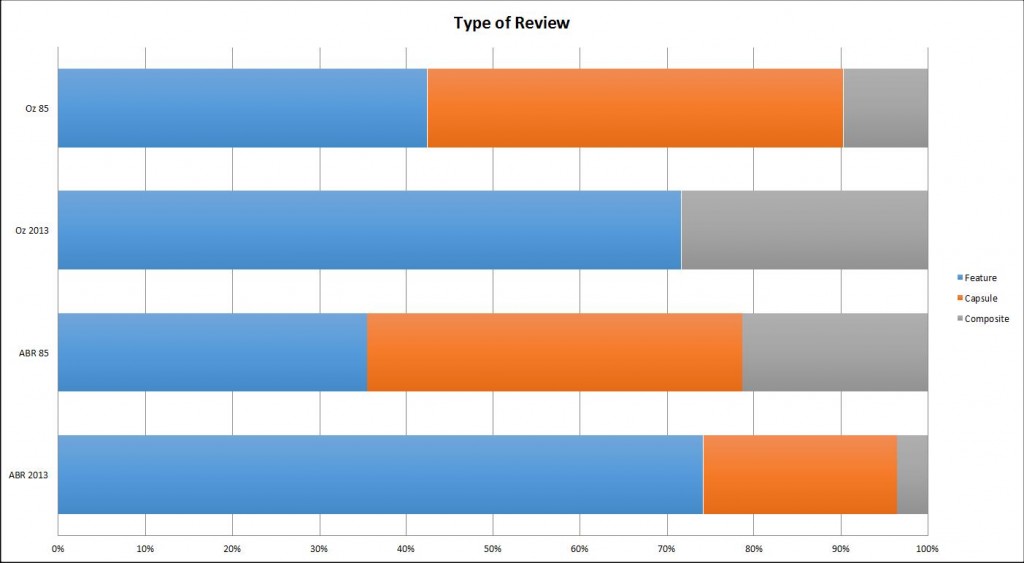

The apparent disparity between increasing page space and decreasing number of books being reviewed can also be explained by changes in the length, and therefore the nature, of book reviews over this period. The major shift we found between 1985 and 2013 is the increasing proportion of feature reviews in both publications. In The Australian, the proportion of feature reviews has increased from 42% to 72% [Figure 6]. In ABR, feature reviews have jumped from 36% to 74% of all reviews. This represents a redisposition of the book pages in these publications. Arguably, it has become a less democratic space than it once was, with the drop in the total number of reviews compounded by the diminishment of the capsule. The book pages are being recast from a space of near-comprehensive noting of new books to one of highlighting major releases. The opportunities for authors and works to be discussed in these pages has significantly diminished.

Figure 6: Type of Review

When we consider these statistics regarding review type and length alongside gender some doubling down in terms of bias becomes apparent. In The Australian in 1985, the vast majority of books reviewed by women—that is 468 of 637 books, or 74%—were capsules. The majority of these capsules were written by only two women: Sandra Hall, who wrote 112 of the 468 capsules, and Vicki Wright, who wrote the remaining 346. Anyone who has reviewed a book for money knows that it doesn’t pay to divide the dollars earned reading the book and writing about it by the time spent. But, equally, anyone who has reviewed a book for money knows that it is economically more worthwhile to review one book at 900 words than 300 words. Writing capsule reviews isn’t easy—conveying a sense of the book and offering some analysis in a small amount of space is a kind of art. Hall and Wright were, we submit, literary-critical sandwich-makers in the sense that they were responsible for doing the low-status, high-volume work in the field.

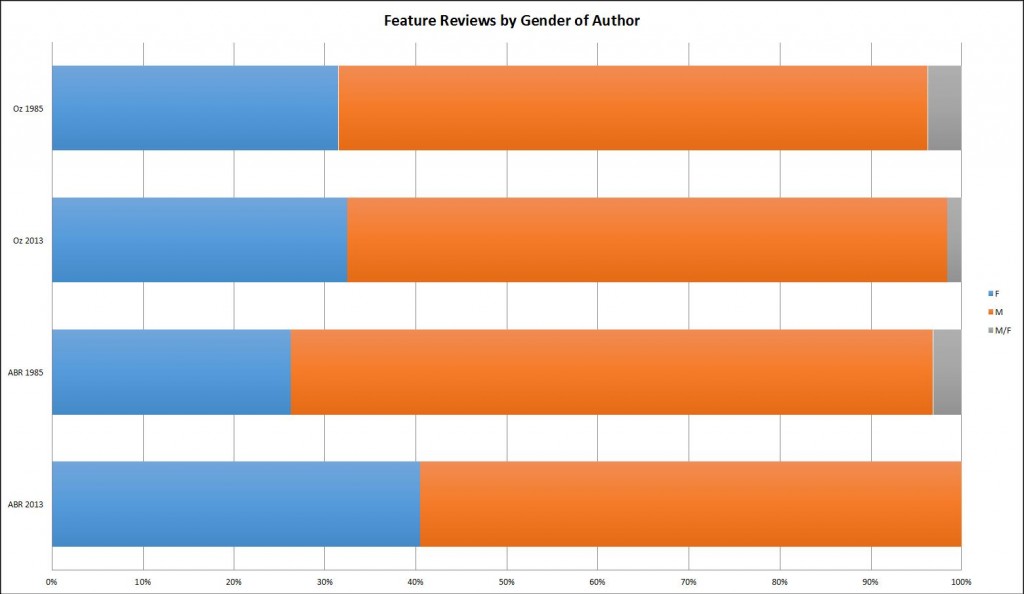

But it is in the most high-profile and prestigious real estate of the book pages—the feature review—that the discrepancy between male and female authors and reviewers is most apparent. In The Australian in 1985, only 31% of feature reviews were of books authored by women; and as reviewers, women were responsible for 30% of all feature reviews: this is significant given that women are responsible for more than 60% of reviews overall in The Australian in that year. The statistics are similar for both publications across 1985 and 2013 [Figure 7]. From the most recent Stella Count, these figures seem fairly representative of the field as a whole: for all Australian publications in 2015, 66% of feature reviews were of books authored by men, and 62% of the total number of feature reviews were written by men.[8]

Figure 7: Feature Reviews by Gender of Author

Figure 8: Feature Reviews by Gender of Reviewer

TABLE

Figure 9: Reviewers of Features

In terms of individual reviewers’ involvement in the writing of feature reviews, we found that in The Australian in 1985 the top five reviewers by number of feature reviews were all men [Figure 9]. In 2013 the top five included one woman, Miriam Cosic, tying for fifth place with James Bradley and Peter Pierce. We speculate that the fact that Cosic is not a freelance reviewer like Bradley and Pierce but employed as a journalist at The Australian goes some way to explaining this. Of the reviewers who wrote more than one feature review in these publications in 1985 and 2013, women constituted 38% and 40% in ABR and 29% to 33% in The Australian. In relation to feature reviews, the balance of critical authority in each of these publications is decidedly male.

VIII. Conclusions and points for future discussion

While the Stella and VIDA pies show ongoing disparity between the reviewing of books by men and women, what they do not show is the ways in which the field as a whole is shrinking and changing shape. On top of the reduction in the number of books being reviewed each year in the Australian print media, the focus of reviews has shifted from coverage or reportage of the field to longer-form discussion. In 2013, if a book is reviewed it is likely to get more attention, but for authors there are fewer chances to have a critic evaluate their work in traditional outlets. Although it appears that gender disparity across time has remained fairly constant, in some respects it is more problematic now than in 1985 because of the fact that men are more likely to be author and subject of the most prestigious and increasingly dominant form of review: the feature review.

In terms of gender, disparity in the scrutiny of books has changed across time in different ways. In the 1980s, a period in which ‘the proportion and number of Australian novels by women increased considerably’ (Bode 143), we might have expected to see some significant interest in books authored by women in major Australian reviewing periodicals. We found that this was not the case. As mentioned above, books by women represented less than a third of all those reviewed in The Australian and ABR in 1985. We find the recurring 60-70:40-30 ratio of gender disparity curious. It occurs in other fields too: a recent survey of artists and subjects of the Archibald Prize, for example, found women’s representation sitting largely at the 28-37% mark (Jefferson). The ‘glass escalator’ effect, in which men stay at the top of the publishing world despite it being a female-dominated industry (Bode 165) might be in effect here. It seems that 40% is some kind of limit beyond which women’s representation in the books pages (and indeed in other cultural spheres) will not go for fear that something—male readers, prestige?—will be lost.

This research is a small step towards a history of book reviewing in Australia, and there is clearly much more to do. We have also found significant shifts in the genre of books being published, the occupation of reviewers, and the publishers of books being reviewed. We are also keen to trace the afterlife of the review and its influence on academic literary criticism. This paper is an intervention into the long history of counting, documenting and forgetting gender bias in the field of book reviewing that has largely taken place outside of the academy. By bringing scholarly attention to bear on these questions, we can begin to understand how these statistics showing gender bias fit into broader histories of literature and publishing in Australia, and map the changes in the scale and shape of the field.

Melinda Harvey is Lecturer in Literary Studies at Monash University and Director of its Centre for the Book. She has worked as a literary critic in Australia for over a decade, reviewing books for publications such as The Australian, Australian Book Review and the Sydney Review of Books.

[sta_anchor id=”bio”]Julieanne Lamond is Lecturer in English at Australian National University and editor of Australian Literary Studies. She has published essays on Australian writers (including Rosa Praed, Barbara Baynton, Miles Franklin and Christos Tsiolkas), gender and Australian literary culture, the history of reading, and popular fiction at the turn of the twentieth century.

Notes

[1] The Wheeler Centre, opened in February 2016 and located in Melbourne’s CBD, houses numerous literary organisations and programs talks by local and international writers and thinkers throughout the year.

[2] We wish to acknowledge the collection done by Anna MacDonald and Jayne Regan, who worked as paid Research Assistants on our 1985 and 2013 datasets, and Imogen Mathew and Ashley Orr, who worked as paid Research Assistants on the 2015 Stella Count. We also wish to acknowledge the financial support of the ANU College of the Arts and Social Sciences, the ANU Gender Institute, as well as the Faculty of Arts and Centre for the Book at Monash University in this research.

[3] We wish to acknowledge the collection done by Anna MacDonald and Jayne Regan, who worked as paid Research Assistants on our 1985 and 2013 datasets, and Imogen Mathew and Ashley Orr, who worked as paid Research Assistants on the 2015 Stella Count. We also wish to acknowledge the financial support of the ANU College of the Arts and Social Sciences, the ANU Gender Institute, as well as the Faculty of Arts and Centre for the Book at Monash University in this research.

[4] In the 2016 ARC Discovery Project Scheme round, only three proposals with the FoR Code 2005 In the 2016 ARC Discovery Project Scheme round, only three proposals with the FoR Code 2005 (Literary Studies) were granted funding out of a total of 635 successful applications—i.e., only 0.47% of the total number of funded projects. This is down from 0.75% in 2015 (ARC).

[5] We include the weekend editions of The Australian from 5-6 January to December 21-22 for both 1985 and 2013, and each of the ten issues of Australian Book Review—from February/March to December/January in 1985 and from February to December/January in 2013. In both 1985 and 2013 there were two bimonthly and eight monthly issues of the Australian Book Review published, but the timing of one of the two bimonthly issues is different. The bimonthly issues in 1985 were for February/March and December/January. For 2013, they were July/August and December/January.

[6] ABR did lapse completely between 1974 and 1978, but this was before the period of our study (Wilde, Hooton and Andrews 53).

[7] The 2013, 2014 and 2015 Stella Counts noticed a total of 3,883, 3,705 and 3,538 reviews respectively.

[8] The 2015 Stella Count does not distinguish between feature and non-feature reviews, but does include a field for size and a composite/not composite field. For this statistic, we included all medium and large reviews that are not composites.

Works Cited

Austlit. ‘Reading by Numbers.’ <http://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/

5962221>. 28 Aug. 2016.

Australia Council. ‘List of Key Organisations.’ <http://www.australiacouncil.gov.

au/strategies-and-frameworks/list-of-key-organisations/>. 29 Aug. 2016.

Australian Book Review. ‘Advertising.’ <https://www.australianbookreview.com.

au/advertise>. 29 Aug. 2016.

Australian Research Council. ‘Scheme Round Statistics for Approved Proposals—Discovery Projects 2016 round 1.’ <https://rms.arc.gov.au/RMS/Report/

Download/Report/a3f6be6e-33f7-4fb5-98a6-7526aaa184cf/5>. 29 Aug. 2016.

Belieu, Erin and Kevin Prufer. ‘VIDA: An Interview with Erin Belieu.’ Literary Publishing in the Twenty-First Century. Eds. Travis Kurowski, Wayne Miller and Kevin Prufer. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions 2016. 101-19.

Bishop, Stephanie. ‘As One in Rejecting the Label of Middlebrow.’ Sydney Review of Books 30 October 2016. <http://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/as-one-in-rejecting-the-label-middlebrow/>. 30 Aug. 2016.

Bode, Katherine. Reading by Numbers: Recalibrating the Literary Field. London: Anthem Press, 2012.

—, and Tara Murphy. ‘Methods and Canons: An Interdisciplinary Excursion.’ Advancing Digital Humanities: Research, Methods, Theories. Eds. Paul Longley Arthur and Katherine Bode. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. 175-93.

Brady, Veronica and Christopher Lee. ‘Criticism (Australia).’ Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English. Eds. Eugene Benson and L. W. Conolly. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005. 284-7.

Caplan, Paula J. and Mary Ann Palko. ‘The Times is not a-changin’.’ The Women’s Review of Books 22.2 (November 2004): 16-7.

Carter, David. ‘Critics, Writers, Intellectuals: Australian Literature and its Criticism.’ The Cambridge Companion to Australian Literature. Ed. Elizabeth Webby. Cambridge UP. 258-93.

—. ‘Publishing, patronage and cultural politics: Institutional changes in the field of Australian Literature from 1950.’ The Cambridge History of Australian Literature. Ed. Peter Pierce. Cambridge UP: 360-90.

Case, Jo. ‘The Count at SWF: on the representation of women writers in reviews, prizes and genre writing.’ Kill Your Darlings 24 May 2011. <https://killyourdarlings.com.au/2011/05/the-count-at-swf-on-the-representation-of-women-writers-in-reviews-prizes-and-genre-writing/>. 19 Aug. 2016.

Coronel, Tim. ‘The Market Down Under.’ Think Australian 2014. Ed. Andrea Hanke. Melbourne: Thorpe-Bowker, 2014. 1-7. <https://issuu.com/bpluspmag/

docs/thinkaustralian2014>. 28 Aug. 2016.

Cunningham, Sophie. ‘The Book Review Maze: An Editor’s Take on Questions of Style, Place and Purpose.’ Australian Author 41.2 (August 2009): 17-8.

Dale, Leigh, and Robert Thomson. ‘Books in Selected Newspapers, December 1930.’ Resourceful Reading: The New Empiricism, eResearch and Australian Literary Culture. Eds. Katherine Bode and Robert Dixon. Sydney UP, 2009. 119-41.

Davis, Mark. Gangland: Cultural Elites and the New Generationalism. St Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 1999.

Dunn, Amanda. ‘Call to Revive Aussie Classics.’ Sydney Morning Herald 22 January 2012. <http://www.smh.com.au/national/education/call-to-revive-aussie-classics-20120121-1qbcw.html>. 29 Aug. 2016.

During, Simon. ‘Comparative Literature.’ ELH 71 (2004): 313-22.

Goldsworthy, Kerryn. ‘Everyone’s a Critic.’ Australian Book Review May 2013: 20-30.

Graff, Gerald. Professing Literature: An Institutional History. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007.

Jefferson, Dee. ‘The Archibald prize finally hit gender parity but where are the women on the walls?’ Guardian 14 July 2016. <https://www.theguardian.

com/artanddesign/2016/jul/14/the-archibald-prize-finally-hit-gender-parity-but-the-exhibition-tells-a-different-story>. 31 Aug. 2016.

Ley, James. The Critic in the Modern World. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

McLaren, John. ‘Book Reviewing in Newspapers, 1948-1978.’ Cross Currents: Magazines and Newspapers in Australian Literature. Ed. Bruce Bennett. Melbourne: Longman Chesire, 1981. 240-55.

Meyer-Lee, Robert J. ‘Toward a Theory and Practice of Literary Valuing.’ New Literary History 46.2 (2015): 335-55.

Munro, Craig, and Robyn Sheahan-Bright. Eds. Paper Empires: A History of the Book in Australia, 1946-2005. St Lucia, Qld: U of Queensland P, 2006.

Murray, Simone. ‘Charting the digital literary sphere.’ Contemporary Literature 56.2 (2015): 311-39.

Noble, D. H. and C. M. A Survey of Book Reviews, Oct-Dec 1973. London: Noble and Beck, 1974.

Nolan, Sybil and Matthew Ricketson. ‘Parallel Fates: Structural Challenges in Newspaper Publishing and their Consequences for the Book Industry.’ Sydney Review of Books 22 February 2013. < http://sydneyreviewofbooks.

com/parallel-fates-2/>. 30 Aug. 2016.

Palmer, Nettie. Nettie Palmer: Her private journal Fourteen Years, poems, reviews and literary essays. Ed. Vivian Smith. St Lucia: UQP, 1988.

Pool, Gail. ‘Book Reviewing: Do It Yourself.’ Women’s Review of Books 25.2 (March-April 2008): 9-10.

—. Faint Praise: The Plight of Book Reviewing in America. Columbia, MO: U of Missouri P, 2007.

The Stella Prize. < http://thestellaprize.com.au/>. 30 Aug. 2016.

VIDA. <http://www.vidaweb.org/category/the-count/>. 30 Aug. 2016.

Watson, George. The Literary Critics: A Study in Descriptive Criticism. Ringwood, VIC: Penguin, 1973.

Wilde, William Henry, Joy W. Hooton and B. G. Andrews. The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature. Oxford UP, 1994.

Williamson, Geordie. The Burning Library: Our Great Novelists Lost and Found. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2012.

Women in Publishing. Reviewing the Reviews: A Woman’s Place on the Book Page. London: Journeyman Press, 1987.

Woolf, Virginia. ‘Reviewing’ [1939]. The Captain’s Death Bed and Other Essays. London: Hogarth Press, 1981, 118-31.

Zwar, Jan. ‘What Were We Buying? Non-fiction and Narrative Non-fiction Sales Patterns in Australia in the 2000s.’ JASAL 12.3 (2012). <http://openjournals.library.usyd.edu.au/index.php/JASAL/article/view/9835/9723> 30 Aug. 2016.