By Hannah Stark

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version.

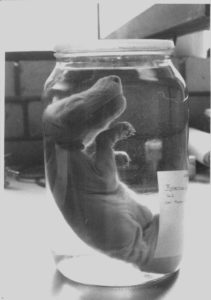

Figure 1: Thylacine pouch young [AMS P762 (♀)]. Courtesy Australian Museum. Photo: Prof. Dr Heinz Moeller. Source: International Thylacine Specimen Database, 5th Revision (2013).

Figure 1: Thylacine pouch young [AMS P762 (♀)]. Courtesy Australian Museum. Photo: Prof. Dr Heinz Moeller. Source: International Thylacine Specimen Database, 5th Revision (2013).

In the introduction to Loss: The Politics of Mourning, David Eng and David Kazanijan write that ‘as soon as the question “What is lost?” is posed, it invariably slips into the question “What remains?” That is, loss is inseparable from what remains, for what is lost is known only by what remains of it, by how these remains are produced, read, and sustained’ (2). This article considers the remains of the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, the last of which died on 7 September 1936 at Beaumaris Zoological Gardens on the Hobart Domain. Since its untimely demise the thylacine has been an enduring presence in the cultural life of Tasmania and has become an international emblem of extinction. This article contemplates the power of thylacine remains to elicit emotions such as guilt, shame or grief in the context of the mass extinction of species that is symptomatic of the Anthropocene. In particular, it considers specimen P762, a female thylacine pup held by the Australian Museum in Sydney but which I discovered on the International Thylacine Specimen Database (ITSD), an amazing digital archive that records the details of over 750 thylacine specimens held in collections all around the world.[1] In turning to these poignant images I want to afford this thylacine pup the status not of curiosity or mute museum object but of a creature whose life and death matters. I also want to consider the ‘afterlife’ of this animal. Here, I take the notion of ‘afterlife’ from a Royal Society lecture given by Katheryn Medlock, senior curator of vertebrate zoology at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) who talked about the ‘afterlife of animals’ when, after death, they enter a museum collection. Considering thylacine specimen P762 provides an opportunity to dwell on the affective capacities of the remains of one thylacine, a body that can be read as a repository for the complexity of the emotions that attend to extinction in the Anthropocene.

Although the last known thylacine died at Beaumaris Zoo in 1936, the sad story of the thylacine shows the ways that extinction has, what Thom van Dooren has called a ‘dull edge’. It occurs not through a single event but as a ‘prolonged and ongoing process of change and loss that occurs across multiple registers and in multiple forms both long before and well after this “final” death’ (58). Thylacines were once found through mainland Australia and New Guinea but from approximately 2000 years ago they existed only in Australia’s island state, Tasmania (‘Tasmanian Tiger or Thylacine’). During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries thylacines were captured, transported and displayed in a range of zoos including Beaumaris in Hobart and the City Park Zoo in Launceston. Outside of Tasmania they were exhibited at zoos in Adelaide, Melbourne, London, Liverpool, Berlin, Paris, Cologne, Antwerp, Washington and New York. The transportation and acclimatisation of these animals was often very fraught. The London Zoo displayed the first and last thylacine outside of Australia. Between the arrival of the first thylacine in 1850 and the death of the last in 1931, 25 animals were transported to London, five of which arrived dead and one which died eight days after landing. After their death, some of these animals were traded with other European institutions and many found their way into museum collections such as the Hunterian Institute of the Royal College of Surgeons, the Zoological Institute in Stockholm and the Natural History Museum in London (Sleightholme and Ayliffe). In Tasmania, thylacines were considered a menace as they were falsely believed to prey on livestock. There were a range of private and industry-based bounties placed on the head of the thylacine, but the most significant was the government bounty from 1888-1909 which paid one pound per adult and ten pence per young (Paddle 166) and led to a severe depletion in thylacine numbers. Their situation as an increasingly threatened species was exacerbated because as they became rarer they also became more desirable to collectors, zoos and museums.

The last thylacine, immortalised as ‘Benjamin’,[2] did not end up in a museum collection because after the animal died at Beaumaris zoo it was deemed that the body was not in good enough condition to preserve (Sleightholme 953). The anthropogenic extinction of the thylacine as a species can be considered an act of settler-colonial violence, sanctioned by government policy and systematically enacted.[3] Similarly, the death of ‘Benjamin’ reveals human miscalculation, negligence and prejudice. Robert Paddle is damning in his assessment of the role of bureaucratic neglect in the death of the last thylacine. This animal, he writes,

could easily have lived much longer in captivity, but it did not, and the reason for its failure to survive lies in a series of insensitive and offensive administrative decisions made by a bureaucratic management structure with no representation from keeper or curatorial staff, no experience in animal care or zoo management and, ultimately, on economic grounds, no interest in the zoo’s continuation. 185

These poor administrative processes and decisions were happening against the background of the depressed economy of the 1930s. One of the more significant impacts of this situation on the zoo was the introduction of a Government work program and the replacement of qualified staff with ‘sussos’ or sustenance workers (Paddle 193). The people tending to ‘Benjamin’ were poorly trained, which lead to an impoverished standard of care. The night that ‘Benjamin’ died s/he had been locked out of her/his sleeping enclosure and probably expired due to exposure, with temperatures dipping below zero degrees Celsius in the last ten days of the animal’s life (Paddle 195). Arguably, the best equipped person to care for Benjamin was Alison Reid, daughter of Arthur Reid, the original zoo keeper at Beaumaris. Alison was described in a feature in South Australia’s The Register News-Pictorial as a ‘foster mother of wilder things’ (‘Beauty’ 7) due to her practice of hand-rearing the zoo animals. The most famous of her charges was the leopard Mike who was removed from the care of his biological mother after she ate his twin and which Alison would walk around the Hobart domain on a lead (‘Beauty’ 7). However, sexist attitudes meant that after her father died she was not permitted to continue to contribute to the life of the zoo to her full capacity. ‘Benjamin’s’ fate was not helped by the prevalent speciesism in Australia at this time; ‘Benjamin’ was not the star attraction at the Beaumaris zoo, but rather the exotic animals such as the polar bears and leopards were the most popular (Hobart City Council). Tragically, ‘Benjamin’ died just after thylacines became a protected species in Tasmania and as such he/she was the only known thylacine to ever live as a protected species (Paddle 185).[4] 7 September, the date of the death of this animal, is now memorialised as National Threatened Species Day.

Historically, living thylacines and specimens were circulated between collectors, zoos and museums in an economic and biopolitical network. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, thylacines held in zoos existed as mere specimens and as part of a logic of species-thinking by which, according to Matthew Chrulew, ‘each individual is only perceived as a token of its inexhaustible taxonomic type’ (141). This logic of kind is also evident in the contemporary museum in which thylacine bodies provide either a repository of genetic material, an artefact of Australian history and/or Australian species diversity, or a cautionary tale about anthropogenic species extinction. We see the latter with the thylacine on display in the Grand Galerie de l’Evolution in Paris, which is presented in a large darkened ‘extinction gallery’ filled with taxidermy mounts of extinct and endangered animals. The scale of this display speaks in complex ways to our current milieu of extinction, which Neel Ahuja describes evocatively as ‘the enormity of killing’ (370). Similarly, thylacine remains in galleries as dispersed as the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, the Musée des Confluences in Lyon and the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh are displayed in extinction cabinets with other extinction celebrities such as the dodo and passenger pigeon. In all of these displays, the interpretive material invites the viewer to think about the larger story of extinction and about the history of the thylacine in broad terms. In replicating the logic of kind, many extinction displays rely on the story of species loss, rather than offering the history or narrative of a particular animal.[5]

The alarming rate at which species are vanishing has made extinction a definitional marker of our time, an era now being described as the Anthropocene. As Michelle Bastian and Thom van Dooren suggest, one of the effects of mass extinction is that it ‘remakes both temporal relations and possibilities for life and death’ (Bastian and van Dooren 2). Timothy Clark writes that one of the key features of the Anthropocene is a derangement in our usual scales of perception (125) and this is clearly evident in the challenge of conceptualising species loss. Temporally, extinction requires that we consider the vast scales of deep pasts and futures, and that we think both in terms of evolutionary time-scales and the urgency of impending species diminishment. Extinction is hard to conceptualise because of its enormity but also because we live in a world filled with species that exist below the level of our perception. This means that we are never fully aware of all the species expiring. In his book Flight Ways, van Dooren suggests that after we put aside background extinction (the regular extinction which is part of natural cycles) the current rate of extinction is between 100 and 1000 times greater than would be expected and that we are set to lose between one-third and two-thirds of all currently extant species (6). Extinction is also ontologically unsettling in that it troubles the possibilities for individual agency and action. In this context, we need to be attentive, van Dooren suggests, ‘to the diverse ways in which humans—as individuals, as communities, and as a species—are implicated in the lives of disappearing others.’ This kind of work has the potential to ‘unsettle human exceptionalist frameworks, prompting new kinds of questions about what extinction teaches us, how it remakes us, and what it requires of us’ (5).

This article considers what it might mean for how we engage with extinction to move beyond this logic of kind and to find ways for the lives and deaths of these animals to matter. In this way, I draw on Judith Butler’s work in Precarious Life, in which she connects being afforded the status of a ‘grievable life’ and mattering politically. She writes, ‘[s]ome lives are grievable, and others are not; the differential allocation of grievability that decides what kind of subject is and must be grieved, and which kind of subject must not, operates to produce and maintain certain exclusionary conceptions of who is normatively human: what counts as a liveable life and a grievable death?’ (Butler xv). For Butler, working in a Hegelian register, to be recognised as worthy of grief is to be considered fully human and a member of a global political community. However, as a number of scholars have noted, the centrality of the human in Butler’s ethical and political framework has been at the exclusion of other animals and has worked to deny the human’s status as animal (Taylor 61; Oliver 226; Stanescu 571). Butler’s notion of the differential of grief could surely be an apt framework for thinking about how some animals such as domestic pets are recognised, elevated, and mourned, while the lives and deaths of the animals processed in industrial farming cannot be mourned or valued beyond their economic status. In a more recent interview with Butler we can see significant potential for accommodating nonhuman animal life in her framework in the following comment: ‘If humans actually share a condition of precariousness, not only just with one another, but also with animals, and with the environment, then this constitutive feature of who we “are” undoes the very conceit of anthropocentrism. In this sense, I want to propose “precarious life” as a non-anthropocentric framework for considering what makes life valuable’ (Antonello and Farneti n.p.). What happens if Butler’s framework is stretched to consider animal life and animal death, to understand that we share a common vulnerability with all living things?

Dana Luciano and Mel Chen bring this notion of precarity together with contemporary environmental crisis and suggest that queer ecologies and engagements with the nonhuman ‘emerge, in the contemporary context, as a response to precarity, as the effects of climate crisis extend that condition to encompass all of humanity, and numerous other species as well. All life, we might say, is now precarious life’ (193). While acknowledging that the impact of the Anthropocene is felt differently by people located in a variety of geographical locations, and in relation to the specificity of race and class, Luciano and Chen’s inclusive approach to precarity resonates in the milieu of extinction. Neel Ahuja describes this shared precarity not as a flattening out of difference but as a new intimacy. ‘In ever more precarious intimacy with the shrinking number of living species’, he writes, ‘we inhabit a queer atmosphere in which the ether of the everyday is marked by senses of transformation and crisis’ (Ahuja 377). But while the flattening out of species in relation to the inevitability of their finitude might be useful we also need to remember the special place of the human in the production of extinction. As van Dooren asks: ‘How might we think through the complex place of human life at this time: simultaneously, a/the central cause of these extinctions; an agent of conservation; and organisms, like any other, exposed to the precariousness of changing environments?’ (5). When is it useful, from a political and discursive perspective, to position the human as one vulnerable species amongst many others? Concomitantly, where must we acknowledge the role of humans, both direct and indirect, as agents of extinction?

Figure 2: Thylacine pouch young [AMS P762 (♀)]. Courtesy: Australian Museum. Photo: Prof. Dr Heinz Moeller. Source: International Thylacine Specimen Database, 5th Revision (2013).

Figure 2: Thylacine pouch young [AMS P762 (♀)]. Courtesy: Australian Museum. Photo: Prof. Dr Heinz Moeller. Source: International Thylacine Specimen Database, 5th Revision (2013).

What happens when thylacine bodies are afforded the status of what Judith Butler calls a ‘grievable life’? What might be gained from spending time dwelling on the remains of one particular animal body? With these questions in mind, I turn to P762, a female thylacine pup in alcohol, dated 1866. She was about six months old at the time of her death (Archer) and now resides in the Australian Museum in Sydney. We know the exchange value of specimen P762 in 1866 because of a letter written by the entomologist and naturalist George Masters to the Australian Museum about the trade he had negotiated for the institution of ‘a large container containing black fish and a young thylacine (in spirit)’ from the Tasmanian Museum for ‘birds, shells and another small box containing 2893 insects’ (quoted in Sleightholme and Ayliffe). This pup, who died 70 years prior to the extinction of her species, has been suspended in alcohol in a museum collection for over 150 years. She is one of only 14 extant pouch young recorded in the ITSD, one of which is preserved as a series of microscopy sections. There are seven images of P762 in the Specimen Database. These are very intimate photographs and I am struck by their poignancy and beauty; in another context, I might have mistaken them for art images. In this way, they are quite different from most of the thousands of images in the ITSD which were taken not for their aesthetic potential but to catalogue for researchers an international collection of specimens. Five of the images of P762 are slightly grainy black and white photographs. The first shows P762 submerged in preserving fluid in a labelled specimen jar which has been placed on a work bench [Figure 1]. Her immersed body is covered in a layer of fur, her eyes are closed, her mouth is shut, one ear is pressed down by the glass surface, and you can see the detail of her whiskers and claws. Two images depict her lying on a white surface with a measuring tape running along her length showing that she takes up approximately 25 centimetres. Of these images, one shows her on her side, in the other her face is obscured but we see the curve of her slender back and her tiny hips [Figure 2]. In one of these images the specimen tag tied around her right ankle is visible and you can just make out the incision that runs down the front of her torso. Her tail is curled [Figure 3]. Two other images show a left and right profile of her face, her paws resting just below her chin, one ear folded up and the other down. The final two images are eerie, ghostly x-rays of her lying in foetal position, one a close-up of her skull. When looking at these photographs, it is hard not to domesticate P762. She is a baby creature; she could almost be a sleeping puppy.

Figure 3: Thylacine pouch young [AMS P762 (♀)]. Courtesy: Australian Museum. Photo: Prof. Dr Heinz Moeller. Source: International Thylacine Specimen Database, 5th Revision (2013).

Figure 3: Thylacine pouch young [AMS P762 (♀)]. Courtesy: Australian Museum. Photo: Prof. Dr Heinz Moeller. Source: International Thylacine Specimen Database, 5th Revision (2013).

Here I am reminded of Freud’s exploration of the word ‘uncanny’ through its definition in a range of foreign dictionaries. In relation to the German heimlich, or homely, he notes that the term is used in relation to domesticated animals: ‘Of animals: tame, companionable to man. As opposed to wild’ (2). But while P762 is eerily familiar she is also a wild creature that provokes the ambivalence concealed within the word heimlich which means simultaneously ‘that which is familiar and congenial’ and ‘that which is concealed or kept out of sight’ (Freud 4). Because of this, Freud notes that ‘heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops toward an ambivalence, until it finally coincided with its opposite, unheimlich’ (4). The unheimlich or uncanny is that which is repressed and which returns to us as a strange but familiar haunting. As a kind of rupture, the uncanny creates instability through disrupting the psyche with something that it thought it had inhibited. The experience of the uncanny is particularly resonant in a settler colonial country like Australia, in which indigenous people were violently dispossessed of their land and ways of life. As Gelder and Jacobs write, in Australia the concept of the uncanny ‘can remind us that a condition of unsettledness folds into this taken-for-granted mode of occupation’ (24) and that this permeates national debates about indigenous sovereignty and reconciliation. Because the thylacine was extinct within 133 years of European invasion, P762’s remains are a poignant rem(a)inder of a species that was lost as a by-product of Western imperial expansion.

Specimen P762 is a liminal creature. She is a radical little boundary crosser: both intimate and strange, creaturely and objectified, profoundly dead and holding out the promise of futurity. As Freud notes, one of the key examples of the uncanny is the re-animation of previously inanimate or dead things and their haunting effects (13). P762, along with M27836 (a skull) and M822 (skin and a skull) are the specimens whose DNA was sampled in the Australian Museum’s resurrection project which began in 2001. Because alcohol (as opposed to formaldehyde) is a DNA preservative, P762’s almost 150-year-old organs were harvested in an attempt to extract viable DNA. Footage of this process can be found in a 2002 science documentary, The End of Extinction: Cloning the Tasmanian Tiger, which shows scientists removing P762 from her ‘liquid tomb’ and attempting to harvest DNA from her kidneys, liver, heart and bone marrow. Although DNA was found, the samples were fragmented and were not viable. They had also been contaminated, revealing a history of (undesired and necessarily unreciprocated) touch between P762 and a range of humans. Mike Archer, the then director of the Australian Museum, commented on the tactile fascination with this pup which led to this contamination in his 2013 TED talk: ‘Every old curator who’d been in that museum had seen this wonderful specimen, put their hand in this jar and pulled it out.’ The de-extinction project was discontinued at the Australian Museum in 2005. While the thylacine has become one of the icons of extinction, this pup specifically, Rosie Ibbotson insists, is one of the ‘“icons” of de-extinction research’ (Ibbotson 83).

The Australian Museum’s ill-fated resurrection project reveals a pronounced biopolitical logic to the human instrumentalisation of animal lives, deaths and biological materials. The existence of ‘frozen arks’ or collections of genetic material, has, according to Chrulew, led to an abstraction of animals to genetic data in which we see a prioritisation of ‘species over individual, code over life, genes over bodies’ (148). He quotes Richard Doyle’s description of molecular biology as: ‘a technoscientific power that works by producing an invisibility of the body whose object is no longer the living organism. It is instead an object beyond living—ready to live, beyond the finitude of an organism and its ongoing interactions with and constructions of an environment’ (148). Specimen P762 is, of course, very dead, but her afterlife as museum object, and the handling and manipulation of her body to extract DNA, positions her value as part of this logic of species-thinking. Resurrection and conservation share a similar logic which facilitates human domination of nonhuman animals. After all, it is through intensive breeding programs that humans can work to counteract, and therefore be redeemed from, their culpability in, anthropogenic species extinction. For Chrulew there is an irony in the fact that the more endangered an animal, the greater the intensification of the breeding programme and consequently the greater the control exerted over the animal body. He describes this ‘regular testing, extraction of fluids, transportation, enforced tranquilisation, separation and recombination of social groups, imposed breeding and the removal of offspring’ as a ‘veritable abduction and rape’ (148). In this context Chrulew describes an animal’s refusal to breed as ‘the last form of resistance available to a caste of creatures entirely at the whim of their kindly protectors’ (137). The handling of P762 in the lab is invasive (a masked male scientist probes her interior cavities), and it forces her into a strange reproductive situation which manifests human desires rather than her own. In this context and in relation to Chrulew’s framing of resistance to biopower, what kinds of agency might we read into the failure of this project? How is the agency of this nonliving museum specimen different to the resistance manifested by living creatures to reproductive intervention? What is at stake here? Can we frame P762’s posthumous ‘refusal’ to give up her genetic ‘secrets’ as a performative feminist and queer rejection of (technoscientific) reproductive futurity?

As part of a visual culture of extinction, Specimen P762 can be understood to have considerable agency. The place of the thylacine in visual culture more broadly has been thoroughly documented by Carol Freeman whose cultural history, Paper Tiger: A Visual History of the Thylacine, examines how human understandings of and interactions with the creature were shaped by its representation. For example, she argues that it was because of staged photographs of a mounted thylacine with a chicken that public sentiment turned on the thylacine and saw it as a threat to farming and the domestic (219). When it comes to extinct animals, their place in visual culture is extremely important, as the access we have to them is often through this medium. For example, I have accessed P762 through the images found in a digital archive, located on a CD ROM and held by only a handful of libraries. Ibbotson is interested in the power of images of the thylacine in debates about de-extinction. The visual record of extinct species is important because not only is it one of the main ways that we access creatures that are no longer here but it also shapes public sentiment. Ibbotson writes ‘visual cultures of de-extinction have additional implications for potential animal lives and experiences, not least in the appropriation of images as proxies for species that can no longer be observed alive. Visual representations thus have significant agency within how these species are remembered, as well as in terms of how biotechnical futures, and the lives of formerly-extinct genetically ‘rescued’ animals, are both envisaged and evaluated’ (81). She describes this as the ‘de-extinctionist gaze’ (84) and writes of the ‘“extinct uncanny” within visual cultures of de-extinction, whereby representations powerfully destabilise previous certainties such as the finality of death and extinction’ (90). Amy Fletcher, argues that the thylacine cloning project is an example of scientific spectacle, and that those promoting the thylacine de-extinction project made use of the extensive public and media interest in this animal (49). The thylacine is apposite here not only because of the thylacine resurrection project but also because of the broader cultural refusal to let this animal die. The prevalence of thylacine sightings and the significant media and public interest that this precipitates speak to a desire for the thylacine’s extinction to be proven through the visual record as well as an inability to acknowledge the finality of extinction.

Resurrection initiatives are politically problematic for a variety of reasons. From a resourcing perspective, it is difficult to justify the enormous expense of de-extinction projects in the face of the impending extinctions that we are currently experiencing. Moreover, the logic by which de-extinction is justified often focusses on the redemption of humans for past actions and inactions and through taking responsibility for creating new species futures. This attitude is exemplified in the view expressed by Mike Archer in many interviews in which he insists that if an animal is extinct because of humans we have an ethical obligation to bring it back. He described this project explicitly as one that could redeem humans because it would ‘reverse one of the great blots of the history of the Colonisation of Australia’ (quoted in Smith 270). Deborah Bird Rose and Thom van Dooren highlight the ethical and political place of affect in debates about extinction and de-extinction in their critique of the environmentalist Stewart Brand. In a pro-de-extinction comment which follows the logic expressed by Archer, Brand declares in a 2013 TED talk: ‘Sorrow, anger, mourning? Don’t mourn, organize’ (quoted in van Dooren and Rose 376). However, what happens politically when we foreclose mourning? When science and technology are positioned as a tool that might redeem humans for their role in anthropogenic species extinction, we see an inability to mourn the finality of extinction. This blocked mourning is problematic for van Dooren and Rose. They write:

In short, in our time of anthropogenic mass extinction, dwelling with extinction—taking it seriously, not rushing to overcome it—may actually be the more important political and ethical work. The reality is that there is no avoiding the necessity of the difficult cultural work of reflection and mourning. This work is not opposed to practical action, rather it is the foundation of any sustainable and informed response. (377)

In relation to past extinctions, we might consider the productive capacity of negative affect such as grief and the associated practice of mourning for shaping a multispecies future. To mourn for P762 is to have an affective connection tied up with the uncanny rupture of an animal who lived in a different historical time and who died well before I was born. It is to mourn across species boundaries and for an undomesticated creature that I have never known, never held, and beheld only through photos. But what is the performative function of this mourning? In the introduction to their volume, Eng and Kazanijan meditate on Walter Benjamin’s work on historical materialism to suggest that a ‘politics of mourning might be described as that creative process mediating a hopeful or hopeless relationship between loss and history’ (2). We might also consider the place for the cultural work of mourning or of what Butler has described in a different context as the productive potential of tarrying with grief. ‘If we stay with the sense of loss’, she writes, ‘are we left feeling only passive and powerless, as some might fear? Or are we, rather, returned to a sense of human vulnerability, to our collective responsibility for the physical lives of others?’ (30). The archive of thylacine remains that I have seen, both on display and in museum storage facilities, both in person and through photographic documentation, has caused me to pause. The extinction of the thylacine did not happen by accident. It was a calculated and sustained extermination of a species, sanctioned by the settler-colonial government and participated in by the public. This species has something to teach us about how extinction happens and the remains that are held in museum collections reveal complex and interlocking stories about empire, the relationships between collectors, museums and zoos, the public desire to look at animals on display, and the individual lives, deaths and afterlives of particular animals. This attests to the important role of museums as guardians of what the Queen Victoria Museum and Gallery (QVMAG) in Launceston has described as the ‘precious little remains’. Engaging with extinct species, particularly in ways that enable bad affect—grief, shame, mourning—can have an impact on environmental sentiments, and the performative construction of the human in a more-than-human world. In mourning species loss, we contribute to a more diverse vision of the commemorative landscape of Australia and one that invites us to consider culpability, responsibility and action in the face of the devastating extinction event in which we are currently enmeshed.

Hannah Stark is senior lecturer in English at the University of Tasmania. She is the Author of Feminist Theory After Deleuze (Bloomsbury, 2016), and the co-editor of Deleuze and the Non/Human (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015) and Deleuze and Guattari in the Anthropocene (Edinburgh, 2016).

Notes

[1] These specimens are concentrated in Australia, Europe (particularly in Germany) and in the UK.

[2] The sex of the ‘last’ thylacine, has been a subject of scholarly debate. For many years this animal was assumed to be male, but close scrutiny of photographs and film footage for the presence or absence of a scrotal sack has led to this being disputed. For the opposing arguments see Sleightholme’s sexing of the animal as male (956) and Paddle’s sexing of the animal as female (191; 198-99). Paddle also casts doubt on the name of this animal, suggesting that ‘Benjamin’ is no more than a cultural myth (198).

[3] In total 2063 bounty claims were made during the period of the government bounty (‘Tasmanian Tiger or Thylacine’).

[4] It is important to remember that regardless of what happened to this individual animal, the species were, by this time, already functionally extinct as they did not have sufficient numbers to reproduce and increase to a stable population.

[5] Being positioned as an exemplar of their kind is something that thylacines problematically share historically with the Aboriginal people of Australia, whose remains have been exchanged and circulated in a similar historical period and through similar networks of collectors and scientific men. We see the logic of kind, in relation to both extinction and indigeneity, in the history of the Tasmanian Museum. Nicholas Smith writes of the extraordinary history of the treatment of Trugannini’s remains (who, at the time of her death 1876, had been actively promulgated as the ‘last’ full blooded Tasmanian aborigine and therefore the last of her ‘kind’ despite clear evidence to the contrary). Trugannini, fearing what would happen to her body, requested that it be put in a bag with rocks and thrown into the ocean. However, this wish was denied and to thwart potential grave robbers her body was secretly buried in the Hobart female factory prison graveyard in South Hobart. Two years later, Trugannini was exhumed by the Royal Society of Tasmania and her skeleton was placed on public display between 1904 and 1947. It wasn’t until 1976 that her body was cremated and the ashes scattered in the D’Entrecasteaux Channel (see Smith).

Works Cited

Ahuja, Neel. ‘Intimate Atmospheres: Queer Theory in a Time of Extinction.’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21.2-3 (2015): 366-85.

Antonello, Pierpaolo, and Roberto Farneti. ‘Antigone’s Claim: A Conversation with Judith Butler.’ Theory & Event 12.1 (2009): n.p.

Archer, Mike. ‘How We’ll Resurrect the Gastric Brooding Frog, The Tasmanian Tiger.’ TEDxDeExtinction, 2013. <https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_archer_how_we_ll_resurrect_the_gastric_brooding_frog_the_tasmanian_tiger#t-667855>.

Bastian, Michelle and Thom van Dooren. ‘The New Immortals: Immortality and Infinitude in the Anthropocene.’ Environmental Philosophy 14.1 (2017) 1-9.

‘Beauty and the Beast at the Hobart Zoo.’ The Register News-Pictorial (Adelaide, SA, 1929-1931) 17 May 1930, 7. <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article54241041>.

Butler, Judith. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso, 2006.

Chrulew, Matthew. ‘Managing Love and Death at the Zoo: The Biopolitics of Endangered Species Preservation.’ Australian Humanities Review 50 (2011): 137-57.

Clark, Timothy. Ecocriticism on the Edge: The Anthropocene as a Threshold Concept. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

Eng, David and David Kazanijan. ‘Introduction: Mourning Remains.’ Loss: The Politics of Mourning. Ed. David Eng and David Kazanijan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Fletcher, Amy. ‘Genuine Fakes: Cloning Extinct Species as Science and Spectacle.’ Politics and the Life Sciences 29.1 (2010): 48-60.

Freeman, Carol. Paper Tiger: A Visual History of the Thylacine. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Freud, Sigmund. ‘The Uncanny’ (1919). Trans. Alix Strachey. <http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf>.

Gelder, Ken and Jane M. Jacobs. Uncanny Australia: Sacredness and Identity in a Postcolonial Nation. Melbourne: Melbourne UP, 1998.

Hobart City Council. ‘Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo.’ 3rd edition, August 2003. <https://stors.tas.gov.au/store/exlibris6/storage/2017/11/07/file_1/144584547.pdf>.

Ibbotson, Rosie. ‘Making sense? Visual Cultures of De-extinction and the Anthropocentric Archive.’ Animal Studies Journal 6.1 (2017): 80-103.

Luciano, Dana and Mel Y. Chen ‘Has the Queer Ever Been Human?’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 21.2-3 (2015): 184-207.

Medlock, Kathryn. ‘Where did all the Tigers Go? Tasmanian Museum Thylacine Collection.’ Royal Society Lecture, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) 7 March 2017.

O’Neill, Patrick, dir. The End of Extinction: Cloning the Tasmanian Tiger. Becker Entertainment, 2002.

Oliver, Kelly. Animal Lessons: How they Teach us to be Human. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Paddle, Robert. The Last Tasmanian Tiger: The History and Extinction of the Thylacine. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002.

Sleightholme, Stephen R. ‘Confirmation of the Gender of the Last Captive Thylacine.’ Australian Zoologist 35.4 (2011): 953-56.

Sleightholme, Stephen R. and Nicholas P. Ayliffe. The International Thylacine Specimen Database (2005), 5th revision, 2013.

Smith, Nicholas. ‘The Return of the Living Dead: Unsettlement and the Tasmanian Tiger.’ Journal of Australian Studies 36.3 (2012): 269-89.

Stanescu, James. ‘Species Trouble: Judith Butler, Mourning, and the Precarious Lives of Animals’ Hypatia 27.3 (2012): 567-82.

‘Tasmanian Tiger or Thylacine.’ Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Tasmanian Government, 20 November 2014. <https://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/conservation/threatened-species-and-communities/lists-of-threatened-species/threatened-species-vertebrates/tasmanian-tiger-or-thylacine>.

Taylor, Chloë. ‘The Precarious Lives of Animals: Butler, Coetzee, and Animal Ethics.’ Philosophy Today 52.1 (2008): 60-72.

Van Dooren, Thom. Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction. New York: Columbia UP, 2014.

Van Dooren, Thom and Deborah Bird Rose (2017) ‘Keeping Faith with the Dead: Mourning and De-extinction.’ Australian Zoologist 38.3 (2017): 375-78.