By Richard J. Martin

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version.

In Act 3, Scene 1 of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the sprite Puck leads the rehearsing players Bottom, Snug, Snout, Quince and Flute astray in the enchanted forest of Athens, boasting:

Sometime a horse I’ll be, sometime a hound,

A hog, a headless bear, sometime a fire;

And neigh, and bark, and grunt, and roar, and burn,

Like horse, hound, hog, bear, fire, at every turn. (97-100)

Puck’s boast focuses on points of equivocation in perception, whereby a sound like a twig snapping appears to mean something—a horse—and then something else—a hound—before being revealed to be another thing, perhaps not even a twig at all. At Puck’s command, imagined things proliferate in the minds of the ‘rude mechanicals’ (3.2.9), piled onto each other in the list that concludes this short quote: ‘horse, hog, hound, bear, fire, at every turn’. Drawing inspiration from Puck’s multiple provocations of the imagination, this paper focuses on the meaning of fire in the southern Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia. As the anthropologist Tim Ingold argues, to perceive is also to imagine; to interpret things through signs is to give them meaning and life. The imagination is therefore ‘not just … a capacity to construct images, or … the power of mental representation, but more fundamentally … a way of living creatively in a world that is itself crescent, always in formation’ (‘Introduction’ 3). For Ingold, to imagine ‘is not so much to conjure up images of a reality “out there”, whether virtual or actual, true or false, as to participate from within, through perception and action, in the very becoming of things’ (‘Introduction’ 3). Contrary to approaches to perception that suggest that equivocation in perception—horse, hog, hound, bear, fire—is best left to yield to the pressures of the ‘real’ world, this focus on the becoming of things suggests that the world is imagined before it becomes real, and that imagining is in fact a part of reality. This presents a clear challenge to mechanistic approaches to the management of complex features of the environment like fire.

Around the world, there is a significant and growing body of literature about human engagements with fire as an indispensable part of the living environment, born of life on the planet at least 400 million years ago (Pyne). As the environmental scientist Pyne puts it:

Life creates and sustains fire’s existence: life supplies the oxygen it breathes, life furnishes the fuels that feed it, and life, in the hands of people, overwhelmingly applies the ignition that sparks it into existence. (199)

More than a chemical reaction, fire is therefore part of the cultural ecology of life on earth. In Australia, research on such cultural ecology has particularly examined Aboriginal practices prior to the arrival of settlers, building on the work of Rhys Jones (‘Fire-stick farming’; ‘Hunters in the Australian coastal savanna’). Research since then has concentrated particularly on Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, where work by Haynes, Lewis, Yibarbuk et al., Russell-Smith et al., McGregor et al. and others has asserted a degree of continuity between the ethnographic present and the pre-colonial and even pre-historical past (contra Schrire). Other work has focused on Central Australia, where Bird et al., Edwards et al., and Vaarzon-Morel and Gabrys have documented practices in the very different environments of that region, similarly maintaining an ethnographic analogy between the present and the past. Langton (Burning Questions; ‘Earth, Wind, Fire and Water’) has also written about fire, drawing on ethnographic material from the Laura Basin of Cape York. As these and other researchers have long concluded, Australia’s landscapes were ‘socialised by fire’ (Head, ‘Landscapes Socialised by Fire’).

Drawing on the above research as well as his own analysis of pioneering texts, Gammage’s publications (The Biggest Estate on Earth;‘Fire in 1788’) argue strongly that Aboriginal people maintained a sophisticated scheme of fire ‘management’ circa 1788. In ‘Fire in 1788’, Gammage dubs such fire management a ‘momentous achievement’: ‘[f]ire truly became an ally, and managing it took a quantum leap, changing the face of Australia’ (285). According to Gammage, Aboriginal people across the continent maintained:

[A] two-tier fire system, using fire first to lay out long-term plant templates which located plants and therefore animals precisely and systematically in the landscape, then to activate templates in rotation for day-to-day use … [and a] continuum of templates across Australia, using locally-different fire regimes, but for similar purposes. (‘Fire in 1788’, 277)

As Gammage and others have documented, colonial settlement severely affected traditional burning practices along with every other aspect of Aboriginal life as people were driven from their ancestral lands and their complex cultural life was disrupted (for accounts of this disruption in the Gulf see Roberts; Trigger, Whitefella Comin’). Notwithstanding such disruption, Gammage argues that the historic Aboriginal achievement of fire management provides a model for successful practice today. As McGregor et al. argue similarly:

Driven by concerns about the failure of western science and management to address ecosystem degradation and species loss, people are looking to the deep ecological understandings and management practices that have guided indigenous use of natural resources for millennia for alternative ways of sustainably managing the earth’s natural resources. (721)

For McGregor et al., like Gammage, this ‘failure of western science and management’ is best remedied through the creation of ‘[e]quitable partnerships between indigenous and non-indigenous researchers and managers … [which] reveal a way of looking after the world that emphasizes human obligations to natural resource management’ (721). While sympathetic to the politics conveyed here, I seek to challenge such eco-management thinking, pointing not just to its potentially instrumentalist effects on indigenous practices, but its conceptualization of human relationships with the environment more generally. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork in the southern Gulf, I herein discuss fire as both an elemental feature of the environment and an imagined thing, as well as a kind of commodity (in the form of smoke produced by burning) which may or may not exist at all.1

For Gammage and other scholars (Mcgregor et al.; Russell-Smith et al.), the ‘rekindling’ of pre-colonial Aboriginal burning practices like the wuurk (glossed as ‘bushfire’) tradition of western Arnhem land provides support for the normative claim that ‘we [i.e. non-Aboriginal Australians] have a continent to learn’. As Gammage puts it: ‘If we are to survive, let alone feel at home, we must begin to understand our country. If we succeed, one day we might become Australian’ (The Biggest Estate on Earth 323).

Figure 1: An Aboriginal man conducting early dry season burning in an ancestral estate area on coastal Ganggalida country, May 2012. Photograph by author.

While phrased somewhat parochially, the sentiment behind this grandiose aspiration reflects a general trend internationally towards more pluralistic forms of natural resource management, frequently premised on market-based conservation instruments which attempt to establish the economic value of ‘environmental’ or ‘ecosystem services’ (Jackson; Norton). This paper approaches the idea of becoming in a somewhat different way, suggesting that Gammage’s longed-for moment in which people finally ‘become Australian’ should be reconceived in terms of ongoing creative interactions between persons and places, where the world is perpetually remade in imaginative ways. As Agrawal and others (Green; Yarrow; Jones and Yarrow) argue, the dichotomy between ‘western’ and ‘indigenous’ knowledge is in many respects a false one, which misconstrues what knowledge is. Following these scholars, I argue that knowledge is better conceived as a practice than a ‘western’ and ‘indigenous’ product like ‘Science’ (capitalized here to suggest the reification of scientific practice as a product), or alternatively ‘IK’ (that is, ‘Indigenous Knowledge’) or ‘TEK’ (that is, ‘Traditional Ecological Knowledge’). Doing so suggests that neither ‘western’ nor ‘indigenous’ knowledge may augment the other but that both understandings of knowledge need to be re-thought.2 Such a re-thinking is particularly difficult in Australia due to the temporal binary established by colonial settlement at 1788, which has tended to result in land use practices as well as the plants, animals and people that are represented as belonging to the continent being perceived as those in place before colonization (see Head, ‘More than human’ 40-41). However, notwithstanding such difficulty, this re-thinking is particularly important in coming to terms with contemporary environmental challenges in the changing environments of Australia’s north.

As I argue, the shift in thinking about the role of the imagination in perception suggested by Ingold contributes to this effort, prompting new imaginings of what fire is and what it means in landscapes around the Gulf, as well as elsewhere. Drawing on fieldwork completed around the Gulf between 2007 and 2013, I discuss how a focus on the imagination sheds light on conflict involving Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal understandings of fire in the region; conflict in which contemporary environmental science interacts with cultural traditions in unexpected and indeed creative ways, as persons and places come into being together.

A Fire Natural Disaster Area

In 2004, a large part of the southern Gulf region was declared a fire natural disaster area by the Australian government following a series of severe late dry season ‘hot’ fires, prompting considerable investment from those identified as ‘stakeholders’ around the region, including: the Commonwealth Government (through the Caring for Country scheme, later called Calling for Our Country); the Northern Territory administration; the Queensland Government; the Northern Land Council (the peak Aboriginal organization on the Northern Territory side of the border); the Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation (the peak Aboriginal organization on the Queensland side of the border); the Darwin Centre for Bushfire Research (formerly Bushfires Northern Territory); the Rural Fire Service (Queensland); conservation agencies including Bush Heritage and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy; and Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal residents, including pastoralists.

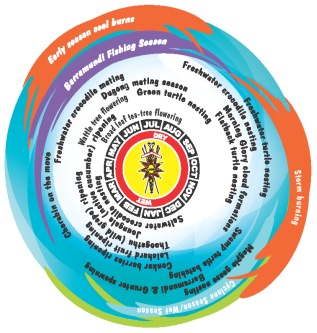

This funding led to the establishment of numerous land management programs, particularly those staffed by Aboriginal people with non-Aboriginal support such as the Ganggalida and Garawa Rangers employed by the Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation on the Queensland side of the Gulf, and the Waanyi/Garawa Rangers employed by the Northern Land Council in the Northern Territory. One outcome of such work was the 2013 publication of a set of fire management guidelines for Queensland’s Gulf country, which identifies thirteen ‘fire landscapes’ in the area and provides information about the distribution of each of these landscapes, their ideal burning ‘mosaic’, burn frequency and season (Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation).3 In addition, this laudable publication includes a seasonal calendar which provides information about Aboriginal resource use and traditional burning regimes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Traditional Seasonal Calendar, courtesy of the Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation.

As Gulf Aboriginal leader Murrandoo Yanner stated at the launch of these fire management guidelines, natural resource management work involving fire has the potential to contribute to the development of collaborations between historically antagonistic parties such as Aboriginal people and pastoralists (Fieldnotes March 2013). Early indications are that this work is proving beneficial, with the anthropologist Sean Kerins noting ‘dramatically alter[ed] … fire regimes’ around the region (12), particularly around the Waanyi/Garawa Nicholson River Aboriginal Land Trust in the Northern Territory where Kerins has worked with Aboriginal Rangers. As the Aboriginal Rangers Jack Green and Jimmy Morrison (facilitated by Kerins) wrote recently:

To see the results of our work you only have to look at the satellite imagery for the south-west Gulf of Carpentaria region. The fire-scar maps clearly show what we have achieved in a very remote region and in tough conditions. Before we got properly underway the fire-scar maps show large areas marked in red, which indicates hot, late-season fires. … Now when you look at the fire-scar maps over the last few years since we have been doing the burning the big areas of red aren’t there. They have been replaced mostly by a pattern of small patches of green colours, which indicates early-season fires. (Green and Morrison with Kerins 194)

As the support of these Aboriginal leaders in the Northern Territory and comparable figures like Murrandoo Yanner in Queensland suggests, such work has the potential to create employment for historically impoverished Aboriginal communities while remaining sensitive to the wishes of local communities, comprising a more participatory approach to natural resource management work than has been accomplished in the past.

However, while a demonstrable improvement on more technocratic ‘top-down’ approaches, natural resource management work such as that described above raises conceptual questions which are often ignored by advocates (de Rijke). While variously defined, such management work is commonly understood as a process that aims to conserve what are construed as ‘natural resources’, the living environment thereby reified as an asset that relates to the socioeconomic, political and cultural needs of current and future generations of human beings. Ecosystem management presumes that human beings have different interests in ‘ecosystem services’, which it attempts to resolve by producing ‘partnerships’ between ‘stakeholders’ construed in various ways, for example between indigenous and non-indigenous people, or between indigenous people and environmentalists, indigenous people and developers, and so on. Across northern Australia, such partnerships are frequently premised on the ‘two toolkits’ or ‘two-ways’ approach to managing land. In a recent collection edited by Altman and Kerins, this ‘two toolkit’ approach is said to combine ‘Aboriginal knowledge’ with ‘Western scientific knowledge’ to comprise a form of land management which selectively draws on the disparate techniques provided by these traditions. For example, Kerins (in another publication) argues strongly that ‘customary early dry season mosaic-burn fire regime[s]’ should be incorporated into regional fire management strategies around the Gulf (‘Building from the Bottom-Up’ 72), appending the adjective ‘customary’ to the scientific argot ‘early dry season mosaic-burn fire regimes’ to suggest the complementarity of these approaches.4 However, while ‘two toolkit’ or ‘two-way’ approaches have some heuristic value (see Altman and Kerins; Ross et al; Strang), they tend towards the enumeration of static contrasts between Aboriginal people and others that are highly contestable. Such contrasts neglect to attend to the more creative aspect of interactions between persons as well as between persons and places, in which the imagination is at work ‘at every turn’ (as Puck puts it in A Midsummer Night’s Dream). Importantly, culture is not a tool that people use to construct their environments, as ‘two toolkit’ or ‘two-way’ approaches suggest. Such approaches fail to adequately conceptualise what fire is and means in landscapes like the Gulf because they fail to properly account for human ‘cultural’ interactions with the environment. As the ecologists Coughlan and Petty acknowledge: ‘[i]n order to understand variability and diversity in human-fire relationships, we clearly need theoretical tools capable of asking the right questions’ (1011). As such, Coughlan and Petty call for ‘a more thorough engagement with social theory and the large body of knowledge that social scientists have accrued on human-environmental interaction’ (1010).

Such theoretical tools are supplied by Ingold in terms of his notion of a ‘dwelling perspective’: ‘a perspective that treats the immersion of the organism-person in an environment or lifeworld as an inescapable condition of existence’ (The Perception of the Environment 153). According to this perspective, the world is not so much ready-made as continually being made, continually becoming. This leads Ingold to a focus on the imagination. Drawing on the work of philosophers like Bergson, Heidegger, and Deleuze and Guattari, Ingold argues:

[P]erception and imagination are one: not however because percepts are images, or hypothetical representations of a reality ‘out there’, but because to perceive, as to imagine, is to participate from within in the perpetual self-making of the world. It is to join with a world in which things do not so much exist as occur, each with its own trajectory of becoming. (‘Introduction’ 14)

As Trigger points out, scholars in natural and physical sciences’ engagements with the humanities and social sciences largely ignore such ideas, remaining restricted to efforts to better effect social change in human attitudes and practices (‘Persons, Objects and Things’). As a result, the bulk of literature focused on the human dimensions of natural resource management in fields like the environmental social sciences and the environmental humanities is routinely ignored. As Head notes, few environmental scientists have read such theory (‘Cultural ecology’ 838-839). While ostensibly focused on the incorporation of alternative cultures within natural resource management work, ‘two toolkit’ or ‘two way’ approaches to managing environments therefore tend to have the effect of ‘compartmentalizing culture’ (as Jackson puts it), enacting the separation of humans from environments. While critiquing this approach is politically problematic when the concept of human ‘impacts’ on the environment is itself contested (as Head notes in ‘Cultural Ecology’ 840), a more sophisticated understanding of the ‘biocultural’ world is necessary to address the ‘natural disaster’ of fire in the Gulf, which is after all hardly a solely ‘natural’ phenomenon. Attending to the role of the imagination in perception enables a much more dynamic engagement with fire as manifesting the ‘self-making’ of the world, on a kind of ‘immanent plane’ of existence, or coming-into-existence (Ingold, Imagining Landscapes 14; Deleuze and Guattari 281). Ethnography from the Gulf illustrates the potential implications of this shift in thinking, turning attention away from historical explanations of fire towards the analysis of what Head (‘More than human’, n. pag) dubs ‘mechanisms of connection, rather than simple correlation’ within the assemblage of humans and fire.

Mechanisms of Connection to Fire in the Gulf Country

In the southern Gulf, fire is associated with Aboriginal spiritual life in complex ways. For many Gulf Aboriginal people into the present, fire is understood as a manifestation of a Dreaming known in English as ‘Bushfire’ which is said to travel inland from the coast following a geographical feature of the environment. Manifestations of smoke in the distance are characteristically said to ‘be’ this Bushfire Dreaming—an illustration of the strength of this powerful Dreaming and the associated importance of country. In contrast, non-Aboriginal residents of the same region tend to associate fire with natural causes like lightning strikes, as well as the actions of Aboriginal people, both of which are understood as unpredictable, if not random, although some pastoralists succumb to paranoid fantasies about Aboriginal people attempting to burn them out. These fears reflect broader changes in social relations brought about by the Aboriginal rights movement since the 1970s, which followed on from the end of widespread Aboriginal employment in the pastoral industry. Recent changes include the award of native title rights and interests over parts of the Gulf, which have given many Aboriginal people permission to access and traverse properties for certain purposes including hunting, fishing and gathering, camping, conducting religious and spiritual activities and ceremonies, and lighting fires (albeit for domestic purposes rather than for hunting or clearing vegetation, although other forms of title possessed by Aboriginal people enable the lighting of fires for land management reasons).5 While the exercise of these rights and interests ideally co-exists with the business of running cattle, some pastoralists have interpreted them as a threat to the continuation of their life on the land—a threat that some Aboriginal people exploit by occasionally threatening to interfere with the running of a herd, for example by ‘lighting up’ a paddock (i.e. setting fire to feed) within the context of localized disputes.6 Meanwhile, pastoralists light their own fires to encourage the spread of certain species (such as introduced Buffel Grass, which responds well to fire), and to assist in mustering cattle (which are drawn to the smell of smoke in the late dry season due to the promise of new grass, known locally as ‘green pick’). Into this mix, scientists concerned with conservation and climate change are seeking to revive what some describe as traditional Aboriginal burning practices, joining bureaucrats from the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency and academics from various universities around Australia in an attempt to put a price on burning, to pay people to light what they incongruously call ‘cool fires’. These preferred fires are mapped in natural colours alongside the stranger pinks and purples of ‘hot fires’ on maps disseminated by the North Australian Fire Information (NAFI) website, producing strange, shifting imaginings of elemental conflict in Australia’s north. However, while such imaginings are clearly distinct from those of classically-oriented Aboriginal people, neither understanding is adequately conceptualized by historical explanations of their difference. As the following vignette describes, a diversity of views abounds in the Gulf region within as well as across the broad ‘racial’ categories of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, manifesting what I have referred to above (following Head) as ‘mechanisms of connection’ to fire.

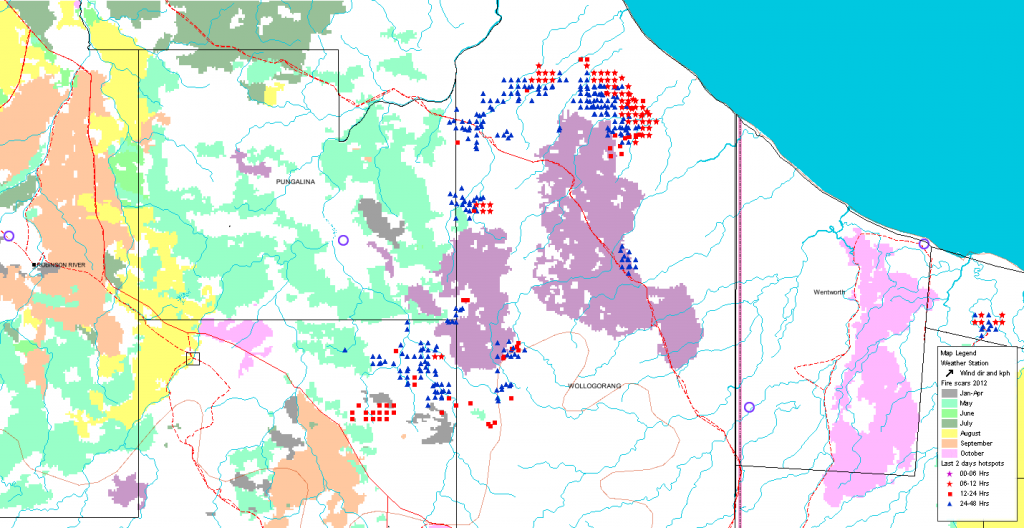

Figure 3: Satellite image from the North Australian Fire Information (NAFI) website, showing active fires and historical fire scars, 15 November 2012.

Figure 3 above is a modified satellite image available on the NAFI website, showing active fires (in red and blue stars, squares and triangles) and historical ‘fire scars’ around Pungalina on November 15th 2012. Around the time that the above image was generated, I visited the area accompanied by eleven Garawa Aboriginal people and another anthropologist (David Trigger) in three four-wheel drive vehicles to interview the non-Aboriginal managers of Pungalina, which is owned by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, or AWC, a not-for-profit environmental organization. The AWC’s ‘sanctuary’ at Pungalina (and Seven Emu, a neighbouring property) is situated on land to which Garawa Aboriginal people maintain strong connections.7 While these connections are highly complex, Garawa people’s desire to maintain their connections largely comes down to the question of access and usage, which is jealously guarded. However, prior to our visit I received a phone call expressing grave concerns about fire hazards associated with our trip. In a voice which quavered with emotion, one of the caretakers employed by the AWC to live on the property spoke of the impact on biodiversity from late-season fires around the Gulf:

It is a travesty. I’m not a scientist but I believe that … burning … is killing everything. … [My partner] saw a fire front this year that was forty kilometres wide, nothing can survive that. … [So] I just want to be clear there is to be no lighting fires [when you come to Pungalina]. … Pungalina is a sanctuary. There’s only this place [where biodiversity is protected] in [the] Gulf. … Everything else is gone. (Fieldnotes November 2012)

According to this woman, Aboriginal people were partly to blame for this situation, with a ‘distorted view that you just chuck matches’. This woman stated:

They [i.e. Garawa Aboriginal people] lit a fire that burnt for weeks [on the Waanyi/Garawa Aboriginal Land Trust at Nicholson River] and that’s what scared me and I thought please don’t let them light fires I would … I think I would slit my wrists. (Fieldnotes November 2012)

However, burning is perceived by many Garawa people as a responsibility with ritual overtones, and Garawa peopledefend this responsibility as part of the law associated with ‘old Wanggala nganinyi’, the ‘old people’ said to have followed the law laid down in the Dreaming (Fieldnotes November 2012; see also Trigger, Whitefella Comin’ 17-18). Country that has not been recently burnt is described by Garawa people as ‘rubbish country’, reflecting a perception of haphazard understory growth as ugly, needing to be cleaned up by burning, ngarrangarra. For many Garawa people, fire is also understood as an illustration of the spiritual potency of country, which is interpreted chauvinistically by those most closely connected to particular areas or ‘estates’ (see Trigger, Whitefella Comin’ 112).8 As we travelled along the long sandy track leading up to the Pungalina homestead, the scene was set for a classic confrontation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal world views.

According to the AWC’s website, threats to Pungalina posed by feral animals and invasive weeds must be controlled, and a ‘fire management program’ must be implemented on the property to assist in the achievement of certain goals, particularly relating to biodiversity:

Merely establishing a sanctuary [at Pungalina and on part of the neighbouring property of Seven Emu] will not protect it. … Pungalina-Seven Emu will only be secure when active, on ground land management is in place. … Strategic burning from the ground and by helicopter can prevent extensive wildfires on Pungalina-Seven Emu. (Australian Wildlife Conservancy)

However, this view occasioned conflict even within that organization. As one of the caretakers at Pungalina explained to me over the phone while detailing her fears about our visit:

We have done so much work here and my fear is … [pause] … I had to really beg … [a senior person in the AWC] not to burn around the property … I said I will whipper snipper it [i.e. mow it], I will weed it, I will do whatever it takes to not have that property burnt, so that was my fear. (Fieldnotes November 2012)

It is worth observing here that the perspective of this non-Aboriginal person is not based on scientific expertise (as she acknowledges above) but rather personal experience and intuition. While feigning obeisance to science with her disavowal (‘I am not a scientist, but’), this woman argued with an ecologist employed by the AWC against that organisation’s clearly defined goals for land management and won a compromise, with only part of this property burnt in the early dry season of that year, 2012 (as Figure 3 illustrates, with a preponderance of bright green on the property, indicating May burns). As a result, this woman was anxious about the build-up of flammable material as the temperature edged closer to 40°C (equivalent to 104°F). As the mention of suicide in the above quotation suggests, this couple (particularly the woman) had invested a great deal of energy in seeking to prevent fire, going so far as to offer to ‘whipper snipper’ and ‘weed’ this enormous property, which covers nearly 200,000 hectares/200 square kilometres (almost 500,000 acres) of sandstone plateau and escarpment, much of which is difficult to access. When I arrived at the property and pointed this out to this couple, I was told by my above informant’s male partner:

We are not against burning but I think it’s got to be controlled to a large degree. We have burnt the boundary of the brook and that is with helicopter and incendiaries and that is to provide a buffer from any wildfires in Queensland and there were some serious wildfires that came from Queensland and burnt right through and that causes people to be a bit paranoid so everybody burns to protect their country and what seems to have happened is that you have a look at the fire site, NAFI, it shows what areas burnt in the Northern Territory and we are one of the little spots that only have early burns on them. (Fieldnotes November 2012)

Like the AWC’s ecologist, whom I interviewed later, these caretakers were both proud of this achievement, having managed to largely ‘control’ late season fires. However, the resemblance between the view of the ecologist on this point and that of these caretakers masks a deeper divide between specialist and lay knowledge that challenges representations of a singular non-Aboriginal understanding of fire.9 As I travelled across the Gulf towards Burketown over the next few days, I recorded a similar diversity of views amongst non-Aboriginal Gulf residents, as well as Aboriginal people.

At a property in Queensland a few days later I mentioned the expressed concerns of the caretakers at Pungalina to a pastoralist, who endorsed them emphatically:

There’s a fire that’s burning around the China Wall [a natural escarpment on the Waanyi/Garawa Aboriginal Land Trust, to the south-east of Pungalina] and if that breaks out, it will run right over the top of them. … You can see it on the NAFI site. (Fieldnotes November 2012)

While this pastoralist dismissed these caretakers as ‘tree-huggers’, she similarly perceived late season fires as a threat, albeit less to biodiversity than to the availability of feed for cattle. Like the Pungalina caretakers, this person referenced the NAFI site as the source of their concerns, identifying fires which none of these people had actually seen. While a simple contrast might be drawn between views informed by access to these NAFI images and that of many Aboriginal people with no access to this website (notwithstanding the Aboriginal Rangers Jack Green and Jimmy Morrison’s reference to the NAFI images in their publication discussed above), it is important to emphasise that such images are not perceived in the vacuum of space but from the perspective of actual engagements in the world: the world, as Merleau-Ponty puts it, ‘of which knowledge always speaks, and in relation to which every scientific schematization is an abstract and derivative sign-language’ (Merleau-Ponty ix, emphasis in the original). While the NAFI images suggest a relatively fixed interpretation or ‘construction’ of the landscape on a two-dimensional plane which might be contrasted with other ‘constructions’, such images are invariably engaged with imaginatively, as contemporary environmental science interacts with cultural traditions in unexpected and indeed creative ways.

As the above example from Pungalina illustrates, non-Aboriginal lay conservationists resident in the Gulf, scientists working at a distance, and local pastoralists differ in their engagements with land and the element of fire, as do Aboriginal people with traditional connections to country at times in some tension with other Aboriginal people in the region who have inherited pastoral properties from their non-Aboriginal forebears. The pastoralist above who was less than positive about the ‘tree-huggers’ at Pungalina-Seven Emu complicates the scene further in that she identifies with some Aboriginal ancestry from south Queensland and moved to the region to marry and subsequently live on and manage a cattle station for many years. However, all residents engage imaginatively with the world. A focus on such imagining suggests ways by which Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal understandings of fire might not merely be accommodated alongside each other, or used to augment each other, but actually integrated into a broadened approach to human-environment relations which stresses more incipient relations between things, including things like smoke which are sometimes said to have no substance at all (see Note 1).

The Weight of Smoke

With the introduction of the Kyoto Protocol and other international schemes to combat climate change, increasing interest has been focused on carbon emissions caused by smoke from burning like that around Pungalina-Seven Emu. In Australia, the ‘Carbon Farming Initiative’ established under the Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Act (2011) has attempted to develop methodologies to quantify the extent of carbon reductions achieved through land management work, preparatory to selling such reduction as carbon credits in a foreshadowed carbon market. Across the northern savannahs, the preferred methodology for assessing carbon reductions has been the creation of vegetation and fire maps to determine the historical or baseline emissions from fire. Emissions reductions are then calculated as the difference between baseline emissions and those able to be achieved through natural resource management burning activities based on simple arithmetic, leading to schemes like the West Arnhem Land Fire Abatement (WALFA project).10 Like Sir Walter Raleigh who reportedly bet with Queen Elizabeth I to be able to weigh smoke, scientific researchers assisted by Aboriginal Rangers have created fire plots which are assiduously mown, their vegetation weighed, then burnt, then reweighed; wagering to thereby be able to calculate the weight of the thing that escapes in the form of trace gases when these fire plots are burnt.11 As an Aboriginal person involved in this work in the Gulf explained:

There’s a process to go through, to make sure it’s real, it has substance, it’s not just on paper. It’s a process with scientists … creating a method for measuring carbon by the metre squared, measure everything [i.e. the entire fuel load of grass and wood], weigh everything, put a fire through then weigh everything again. That’s the bush lawyer’s explanation for it. (Fieldnotes May 2013)

As Mahanty et al. observe of similar schemes in place around south-east Asia, this process transforms carbon ‘sequestered’ in the environment into a commodity which is own-able and controllable, individuated into legally bounded entitities able to be displaced from the context in which they were produced, and then monetized (188). The effect of this is to turn something—air—that has historically belonged to no-one in particular into something that may be sold. Here the mechanisms of connection described above acquire a new dimension, as the effort to turn evanescent smoke into a measurable and in some respects tangible thing—carbon—prompts changes not just to existing burning practices involving Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the region, but to the nature of this assemblage of humans and fire, indeed to ‘nature’ itself.12

Significantly, through the involvement of Aboriginal organisations like the Northern Land Council and the Carpentaria Land Council, burning work conducted under the Carbon Farming Initiative acknowledges and in some respects incorporates classical Aboriginal role-relationships to country as well as a diversity of non-Aboriginal views about fire, creating new networks between people as well as between people and places across the broader north of Australia. In this part of the Gulf country, classical Aboriginal connections to place are based on a form of traditional social organization which counter-balances ritual responsibilities between those connected to ‘estates’ in the area through their father’s father and mother’s mother (persons known as mingaringgi in Garawa), and those with connections based on descent from their mother’s father and father’s mother (known as junggayi). Interviewed in early 2013, an Aboriginal man involved in the Waanyi/Garawa Rangers explained the way in which these role-relationships are incorporated into contemporary burning work:

Junggayi have to do it [i.e. burning], as long as mingaringgi there with him to tell him to do it. Or that junggayi can [burn] … anywhere you not close to sacred site, around sacred site it got to be that junggayi. When we go out we make sure we take junggayi people for that area, and owner we call mingaringgi side you know. … We have it there for lots of reasons ‘cause that way you won’t have people talking: ‘Oh he’s going burning in that country without that … junggayi’. … They make sure they have two partner there together. We do a fair bit in the helicopter. In the front we have the owner [i.e. mingaringgi], the owner of the country and in the back firing that [incendiary] capsule out he’s a junggayi person. … We train up all the junggayi, and all the owner/minggaringi together. Well that way if anything happen well they know. … Not only men, women involved too. We have woman and kid with us when we do burning. (Fieldnotes May 2013)

The incorporation of classical Aboriginal role relationships to country within natural resource management burning work like this is a notable illustration of a transformed system of law and custom for contemporary engagements with the world. But as well as an example of continuing customary law, such practices highlight something new. As the Aboriginal Ranger quoted above went on to explain:

It’s not a big area [of Aboriginal land in the Gulf], only small smoke, so we have to join partner with some other mob … so we can do it together, that way we can get that carbon thing a bit more, we have to join up with some other mob.13 Soon as we can get some buyer. That’s the reason we’re burning around, we’re doing all this [fire work]. (Fieldnotes May 2013)

It is clear that ‘big’ smoke only appears as such through labour, as ‘science’ is marshalled to create value and disaggregate ‘carbon’ from the relational spatialities which produce it to ensure the ‘commensurability’ of smoke across discrete ‘sphere[s] of human action (the environment, the economy, development, etc.)’ (Dalsgaard 80). However, of interest here is the way in which diverse local understandings of the environment, for example those that many Aboriginal people possess concerning the roles that junggayi and mingaringgi ought to play in burning work, interacts with the attempt to assess the economic value of burning within a capitalist mode of production. For many Aboriginal people, the appropriate performance of the role-relationships of junggayi and mingaringgi are critical to the success of such burning work, regardless of the measurable outcomes. However, the work of measuring such outcomes, and operating within a framework which necessitates such measurement, is changing the nature of these roles, and the meaning of caring for country, as Aboriginal people around the region begin to talk about ‘hot’ fires and ‘cool’ fires, and ‘biodiversity’ and even ‘climate change’. While drawing on a transformed system of law and custom, such natural resource management burning work involves socio-economic conditions that eclipse the Aboriginal domain, producing something genuinely new.

While frequently described in terms of partnerships between ‘the world’s oldest cultures’ and ‘Western science’ which reinstates ‘traditional fire management regimes’ through ‘two toolkit’ or ‘two-way’ approaches, such work is arguably better seen as a response to the changing present rather than the past, in futurity shaped by the proxy calculus of anticipatory governance about fire established under the Carbon Credits legislation and other related initiatives. Here diverse perceptions of fire are made commensurate through the creation of carbon as a commodity, that is a socialized entity, albeit one whose meaning and significance varies among actors across different social settings (Mahanty et al. 190), notwithstanding its financialisation within a common economy of ecosystem ‘services’ (Yusoff 3). Rather than the restoration of a historical Aboriginal achievement of ‘fire management’, such practices illustrate how people re-imagine the world, indeed how the world imagines and re-imagines itself into a future shaped by climate change.

Conclusion

As I described at the beginning of this paper, Puck plays on the imagination of the hapless ‘mechanicals’ throughout A Midsummer Night’s Dream, gleefully sowing the confusion that drives the plot. In that play, the character of Theseus presents a clear contrast to Puck, favouring commonsense and rational respectability over play. Towards the end of the play, in Act 5, Scene 1, Theseus complains:

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them into shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Such tricks hath strong imagination… (14-18)

According to this view, the imagination acts on the landscape to give substance to things which do not otherwise exist: ‘bod[ying] forth’, as Theseus puts it, such that ‘[t]he forms of things’ thereby perceived are really epiphenomena of the mind. Without ‘the poet’s pen’, the material world would presumably be present more clearly, allowing men like Theseus to manage it more adeptly. Drawing inspiration from Puck, I have pursued a different interpretation of the imagination, following Ingold and other thinkers in the humanities and social sciences (Jackson; Head, ‘Cultural Ecology’) in seeking to avoid the ontological separation of culture and nature. Against a view of the self as acting on a world which is separate from the self, I argue for an interpretation that presents humans as always already involved in the world, not so much impacting on it as ‘corresponding’ to it or with it as they dwell (Ingold, ‘Introduction’). While there is a danger of unreflective anthropocentrism in such thinking, as Trigger has warned (‘Persons, Objects, and Things’), there is also an incitement to take seriously the meaning of being in the world.

While research has heretofore sought to focus attention on Aboriginal burning as having an historically beneficial impact on the environment in particular conjunctions of time and space which it is argued might again be conjoined, this paper argues instead for attention to the ways in which fire makes sense in terms of people’s relations with each other and with the world in ways that are continually, eternally, created anew. This perspective is particularly well suited to fire. As an Aboriginal Ranger involved in fire work around the Gulf stated during an interview for this paper, ‘A lot of fires have a mind of their own’ (Fieldnotes May 2013). As a non-Aboriginal man working with this Ranger similarly stated:

I’ve been out on country and a fire will appear out of nowhere. I’ve been up in a helicopter, true God, and a fire will just start from nothing. Fire is a funny thing, it can travel, I believe it can move underground … and pop up somewhere else. I tell you I’ve seen things that I can’t explain. (Fieldnotes May 2013)

In further discussion, this man stated that he sometimes associated such unexplained appearances of fire with Aboriginal beliefs, suggesting an imaginative engagement with the world that resonated with Aboriginal traditions. Attempts to measure the weight of smoke offer another example of the role of the imagination in the perception of the environment which blends elements of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal work in interesting ways, suggesting a need to move beyond reductive characterisations of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people engaged in conflict over land management in northern Australia. With its focus on multiple ‘mechanisms of connection’ between humans and fire, this essay has sought to construct or put into circulation an incipient imagining of fire as neither a solely ‘social’ fact nor a simply ‘natural’ phenomenon but something else entirely: a new kind of collective or assemblage. While attempts to turn fire into a commodity in the form of smoke or carbon may come to play an important role in combatting climate change into the future as part of this assemblage, other imaginings of fire may also be necessary, outside the confines of market-based thinking, building on the incipient connections I have described here.

Richard Martin is a postdoctoral research fellow and consulting anthropologist in the School of Social Science at the University of Queensland. His academic research focuses on issues of land and identity in the southern Gulf of Carpentaria. He has also conducted applied research on native title claims and Aboriginal cultural heritage matters around Queensland.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my research participants around the Gulf country, including the many Aboriginal Rangers employed across the region doing work with fire in very difficult contexts. I would also like to thank David Trigger (University of Queensland), Sarah Whatmore (Keble College, Oxford University), Lesley Head (University of Wollongong) and Gay Hawkins (University of Queensland) who provided feedback on an early draft of this paper at the University of Queensland workshop ‘Natures, Cultures, Identities, Materialities’ on 25 and 26 March 2013. Sally Babidge, Kim de Rijke, Ana Dragojlovic, Gillian Paxton and Anna Cristina Pertierra at the University of Queensland and two anonymous reviewers for the Australian Humanities Review also provided valuable feedback. Fieldwork in the Gulf was supported by ARC Discovery Project Number 1201 00662 on which I collaborate with David Trigger. The Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation provided support and assistance on numerous occasions when I was in the field.

Notes

1 Australian legislation relating to the creation of smoke as a commodity is currently subject to intensive political dispute. In widely reported comments on 15th July 2013, the then-Leader of the Opposition (now Australian Prime Minister) the Honourable Tony Abbott described a proposed Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) to journalists in the following way. He stated: ‘This [i.e. the trade in carbon credits] is not a true market, just ask yourself what an ETS is all about, it’s a so-called market in the non-delivery of an invisible substance to no-one’ (cited in Wilson ‘Tony Abbott pours scorn’, n. pag.). While avowing a commitment to restricting carbon emissions, Prime Minister Abbott has promised to repeal legislation which imposes a price on carbon emissions like smoke from fire. Within this context, support for this putative market in carbon has come to parse broader political positions, functioning as an insignia of progressive thinking in Australia (see, for example, Daley ‘Can there by a ‘free market’ in carbon?’; Wilson ‘IPA responds: Property rights and the ETS’).

2 Howitt and Suchet-Pearson’s work in ‘Rethinking the Building Blocks: Ontological pluralism and the idea of “management”’ manifests a related attempt to challenge the dominant idea of management as ‘an unproblematic and universally endorsed goal for communities, regions and nations in their environmental and development discourses’ (323). However, Howitt and Suchet-Pearson’s notion of ‘ontological pluralism’ appears to revive the abstractions that scholars like Agrawal critique.

3 The Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research’s publication ‘People on Country: Waanyi/Garawa’ provides information about related outcomes from funding received by Waanyi/Garawa Rangers in the Northern Territory.

4 The language here reflects a recent trend in ecological thinking towards the promotion of heterogeneity in burning patterns under the rubric of ‘pyrodiversity’ through ‘patch mosaic burning’, described by Parr and Andersen as the attempt to reproduce a range of fire histories across space and time, in effect re-creating the conditions which shaped the spread of plants and animals in places like the Gulf.

5 For a list of rights recognised by the partial determination of the Ganggalidda and Garawa People’s native title claims see the National Native Title Tribunal’s publication Gangalidda and Garawa People’s native title determination, Far North Queensland, 23 June 2010. Updates regarding the status of other native title claims in the region are provided on the National Native Title Tribunal’s website.

6 I am not aware of any instances when Aboriginal people have deliberately set fires to burn feed in the Gulf.

7 Seven Emu is owned by a Garawa Aboriginal man who has agreed to sub-lease part of his property to the AWC for nature conservation purposes.

8 On a fieldtrip in 2012 to a site associated with Bushfire Dreaming in Queensland, I recorded a difference of opinion between Aboriginal people about the ‘smokiness’ of a particular hill, with a senior person’s view that ‘It used to be … full of smoke around this country’ disputed by a younger person who stated: ‘He [i.e. this site and the ancestral powers associated with it] bin [i.e. was] smoky for me…. When I was up there that bushfire coming up from coast and I get up and go show myself. Bit smoky around. I was making noise there all day and that night that fire come there and check me out’ (Fieldnotes May 2012).

9 See Wynne for a related discussion of the tension between specialist and lay knowledge. I also note here that notwithstanding this tension about fire on this trip, relations between the AWC and Garawa Aboriginal people connected to the Pungalina-Seven Emu property area appear to be positive, with both parties expressing the desire to establish closer relations into the future extending into work to control fires and prevent disputes like those I describe here.

10 As Whitehead et al. describe, the WALFA project developed in the context of the Darwin Liquefied Natural Gas PL development at Darwin Harbour. In an attempt to ‘offset’ its carbon emissions, the developers agreed to provide approximately $1 million every year for 17 years (from 2006) to Aboriginal organisations in coastal Maningrida to undertake ‘fire management’. As the Northern Territory’s then-Environment Minister Marion Scrymgour stated in a press release at the launch of this project: ‘This is an historic agreement – a first of its kind for the world – that brings together the world’s oldest cultures with Western science…. It is also the first time that a major energy company has formed a partnership with Aboriginal Traditional Owners to foster a return to traditional fire management regimes leading to a subsequent reduction in greenhouse gases’ (North Australian Land Manager).

11 The (possibly apocryphal) claim that Sir Walter Raleigh bet with Queen Elizabeth I to be able to weigh smoke is found in Lawton B. Evans’s classic America First.

12 An alternative way of conceptualizing this is via Latour’s notion of ‘circulating reference’. For Latour, ‘there is neither correspondence, nor gaps, nor even two distinct ontological domains [of language and nature], but an entirely new phenomenon: circulating reference’ (24). Here Latour seeks to dissolve the distinction between construction and representation, suggesting that scientific practices and products do more than merely resemble nature, instead becoming part of nature, part of the collective or assemblage that humans and non-humans create.

13 In Aboriginal English and Australian English more broadly, the word ‘mob’ denotes ‘an Aboriginal tribe or language group’, or, more generally, ‘a community’ of some kind (see The Macquarie Dictionary Online). The usage here is interesting insofar as it seems to specifically exclude non-Aboriginal people, for while such burning work takes place on a property adjoining Pungalina-Seven Emu, it is striking that the Australian Wildlife Conservancy was to my knowledge not considered as a suitable partner for ‘join[ing] up’ with the Waanyi/Garawa Rangers.

Works Cited

Agrawal, Arun. ‘Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge.’ Development and Change 26 (1995): 413-439.

Altman, Jon C., and Séan Kerins, eds. People on Country: Vital Landscapes, Indigenous Futures. Sydney: Federation Press, 2012.

Andersen, Alan. ‘Cross-cultural Conflicts in Fire Management in Northern Australia: Not so black and white.’ Conservation Ecology 3.1 (1999): 6. <http://www.consecol.org/vol3/iss1/art6/> 1 Nov. 2013.

Aslin, Heather J., and David H. Bennett. ‘Two Tool Boxes for Wildlife Management?’ Human Dimensions of Wildlife: An International Journal 10.2 (2005): 95-107.

Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC). ‘Biological surveys of Pungalina-Seven Emu will be a priority for AWC.’ Australian Wildlife Conservancy. <www.australianwildlife.org/Pungalina/Management-Priorities.aspx> 9 July 2013.

Bird, Douglas W., Rebecca Bliege Bird, and Christopher H. Parker. ‘Aboriginal Burning Regimes and Hunting Strategies in Australia’s Western Desert.’ Human Ecology 33.4 (2005): 443-464.

Bird, Rebecca Bliege, et al. ‘The “fire stick farming” hypothesis: Australian Aboriginal foraging strategies, biodiversity, and anthropogenic fire mosaics.’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105.39 (2008): 14796-14801.

Bowman, David M., et al. ‘Fire in the Earth System.’ Science 324.5926 (2009): 481-484.

Butler, Susan, ed. Macquarie Dictionary. 5th ed. Sydney: Macquarie Dictionary Publishers, 2009.

Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation. Gulf Savannah Fire Management Guidelines. Cairns: Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation, 2013.

Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research. ‘People on Country: Waanyi/Garawa.’ <http://anu.edu/caepr/country/waanyigarawa.php>. 24 Jun. 2013. Link no longer active.

Coughlan, Michael R. and Aaron M. Petty. ‘Fire as a dimension of historical ecology: a response to Bowman et al. (2011).’ Journal of Biogeography 40 (2013): 1010-1012.

Daley, John. ‘Can there be a “free market” in carbon?’ The Conversation 22 July 2013: n. pag. <http://theconversation.com/can-there-be-a-free-market-in-carbon-16266>. 1 Aug. 2013.

Dalsgaard, Steffen. ‘The commensurability of carbon: Making value and money on climate change.’ HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3.1 (2013): 80-98.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. Trans. Brian Massumi. London and New York: Continuum, 2004.

de Rijke, Kim. ‘Review of People on Country: Vital Landscapes, Indigenous Futures.’ The Australian Journal of Anthropology 24.3 (2013). In press.

Edwards, G. P., et al. ‘Fire and its management in central Australia.’ The Rangeland Journal 30.1 (2008): 109-121.

Evans, Lawton B. America First—100 Stories from Our History. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Yesterday’s Classics, 2010 [1920].

Gammage, Bill. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2011.

—. ‘Fire in 1788: The Closest Ally.’ Australian Historical Studies 42.2 (2011): 277-288.

Green, Jack, and Jimmy Morrison, facilitated by Seán Kerins. ‘No more yardin’ us up like cattle.’ People on Country: Vital Landscapes, Indigenous Futures. Ed. Jon C. Altman, and Séan Kerins. Sydney: Federation Press, 2012. 190-201.

Green, Lesley J. F. ‘“Indigenous Knowledge” and “Science”: reframing the debate on knowledge diversity.’ Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress 4.1 (2008): 144-163.

Greenblatt, Stephen. The Norton Shakespeare: Based on the Oxford Edition, Second Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008.

Haynes, C. D. ‘The pattern and ecology of munwag: traditional Aboriginal fire regimes in north-central Arnhemland.’ Proceedings, Ecological Society of Australia 13 (1985): 203-214.

Head, Lesley. ‘Cultural ecology: the problematic human and the terms of engagement.’ Progress in Human Geography 31.6 (2007): 837-846.

—. ‘Landscapes Socialised by Fire: Post-Contact Changes in Aboriginal Fire Use in Northern Australia, and Implications for Prehistory.’ Archaeology in Oceania 29.3 (1994): 172-181.

—. ‘More Than Human, More Than Nature: Plunging into the River.’ Griffith Review 31 (2001): 37-43.

Howitt, Richard, and Sandra Suchet-Pearson. ‘Rethinking the Building Blocks: Ontological pluralism and the idea of “management”’. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 88.3 (2006): 323-335.

Ingold, Tim. ‘Introduction.’ Imagining Landscapes: Past, Present and Future. Ed. Monica Janowski and Tim Ingold. Surrey: Ashgate. 1-18.

—. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, 2000.

Jackson, Sue. ‘Compartmentalising culture: the articulation and consideration of Indigenous values in water resource management.’ Australian Geographer 37.1 (2006): 19-31.

Jones, Rhys. ‘Fire-stick farming.’ Australian Natural History 16 (1969): 224-228.

—. ‘Hunters in the Australian coastal savanna.’ Human ecology in savanna environments. Ed. David R. Harris. New York: Academic Press, 1980. 107-146.

Jones, Sian, and Thomas Yarrow. ‘Crafting Authenticity: An ethnography of conservation practice.’ Journal of Material Culture 18.1 (2013): 3-26.

Kerins, Seán. ‘Building from the bottom-up.’ Proceedings of Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga International Indigenous Development Research Conference. Auckland, New Zealand: Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, 2012.

Langton, Marcia. Burning Questions: Emerging environmental issues for indigenous peoples in Northern Australia. Darwin: Centre for Indigenous Natural and Cultural Resource Management, Northern Territory University, 1998.

—. ‘Earth, Wind, Fire and Water: The social and spiritual construction of water in Aboriginal societies.’ The Social Archaeology of Australian Indigenous Societies. Ed. Bruno David, Bryce Barker and Ian J. McNiven. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2006. 139-160.

Latour, Bruno. Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Lewis, Henry T. ‘Fire technology and resource management in Aboriginal North America and Australia.’ Resource Managers: North American and Australian Hunter-Gatherers. Ed. Nancy M. Williams and Eugene S. Hunn. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1982. 45-68.

Lewis, Henry T. ‘Ecological and technological knowledge of fire: Aborigines versus park rangers in northern Australia.’ American Anthropologist 91.4 (1989): 940-961.

McGregor, Sandra, et al. ‘Indigenous Wetland Burning: Conserving Natural and Cultural Resources in Australia’s World Heritage-listed Kakadu National Park.’ Human Ecology 38 (2010): 721-729.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. Colin Smith. London: Routledge, 1962.

National Native Title Tribunal. Gangalidda and Garawa People’s native title determination, Far North Queensland, 23 June 2010. Cairns: National Native Title Tribunal, 2010.

North Australian Land Manager. ‘Fire Agreement to Strengthen Communities.’ Web. <http://savanna.cdu.edu.au/view/250363/fire-agreement-to-strengthen-communities.html>. 1 Nov. 2013.

Norton, Bryan G. ‘Biodiversity and Environmental Values: In search of a universal earth ethic.’ Biodiversity and Conservation 9.8 (2000): 1029-1044.

Parr, Catherine L., Alan N. Andersen. ‘Patch Mosaic Burning for Biodiversity Conservation: A critique of the pyrodiversity paradigm.’ Conservation Biology 20.6 (2006): 1610-9.

Pope, Alexander. ‘Pope’s Preface.’ Pope’s Iliad. Ed. Felicity Rosslyn. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1985. 1-6.

Pyne, Stephen J. ‘Pyric Other, Pyric Double: Fire Tame, Fire Feral, Fire Extinct.’ Australian Humanities Review 52 (2012): 199-203. <http://www. australianhumanitiesreview.org/archive/Issue-May-2012/pyne.html>

Ritchie, David. ‘Things Fall Apart: The end of systematic Indigenous fire management.’ Culture, Ecology and Economy of Fire Management in North Australian Savannas: Rekindling the Wurrk Tradition. Ed. Jeremy Russell-Smith, Peter Whitehead and Peter Cooke. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing, 2009. 23-40.

Roberts, Tony. Frontier Justice: A history of the Gulf country to 1900. St. Lucia: U of Queensland P, 2005.

Ross, Annie, et al. 2011. Indigenous Peoples and the Collaborative Stewardship of Nature: Knowledge binds and institutional conflicts. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2011.

Russell-Smith, Jeremy, Peter Whitehead, and Peter Cooke, eds. Culture, Ecology and Economy of Fire Management in North Australian Savannas: Rekindling the Wurrk Tradition. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing, 2009.

Schrire, Carmel. ‘Interactions of past and present in Arnhem Land, Australia.’ Past and present in hunter gatherer studies. Ed. Carmel Schrire. Florida: Academic Press, 1984. 67-93.

Strang, Veronica. Uncommon Ground: Cultural landscapes and environmental values. Oxford: Berg, 1997.

Trigger, David. ‘Persons, Objects and Things: Anthropology’s necessary anthropocentrism.’ Paper presented at A post-human world? Rethinking anthropology and the human condition conference. University of Sydney, 13-14 June 2013.

—. Whitefella Comin’: Aboriginal responses to colonialism in northern Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992.

Vaarzon-Morel, Petronella, and Kasia Gabrys. ‘Fire On The Horizon: Contemporary Aboriginal burning issues in the Tanami Desert, central Australia.’ GeoJournal 74.5 (2009): 465-476.

Whitehead, Peter. ‘The West Arnhem Land Fire Abatement (WALFA) Project: the institutional environment and its implications.’ Culture, Ecology and Economy of Fire Management in North Australian Savannas: Rekindling the Wurrk Tradition. Ed. Russell-Smith, Jeremy, Peter Whitehead, and Peter Cooke. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing, 2009. 287-312.

Wilson, Lauren. ‘Tony Abbott pours scorn on the concept of an ETS.’ The Australian 15 July 2013. <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/chris-bowen-admits-the-cost-of-an-early-move-to-an-ets-will-be-significant/story-fn59niix-1226679555111> 15 Jul. 2013.

Wilson, Tim. ‘IPA responds: Property rights and the ETS.’ Climate Spectator 19 July 2013. <http://www.businessspectator.com.au/article/2013/7/19/ carbon-markets/ipa-responds-property-rights-and-ets>. 1 Aug. 2013.

Wynne, Brian. ‘Elephants in the rooms where publics encounter “science”?: A response to Darrin Durant, “Accounting for expertise: Wynne and the autonomy of the lay public”.’ Public Understanding of Science 17 (2008): 21-33.

Yarrow, Thomas. ‘Negotiating Difference: Discourses of indigenous knowledge and development in Ghana.’ PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 31.2 (2008): 224-242.

Yibarbuk, Dean, et al. ‘Fire ecology and Aboriginal land management in central Arnhem Land, northern Australia: a tradition of ecosystem management.’ Journal of Biogeography 28.3 (2001): 325-343.

Yusoff, Kathryn. ‘The valuation of nature: The Natural Choice White Paper.’ Radical Philosophy 170 (2011): 2-7.