By Maria Nugent

© all rights reserved. Printer friendly PDF version.

In memory studies in recent years, increased attention has begun to be given to the circuits that memories—broadly defined—take as they move across time and space (Erll; Levy and Sznaider; Kennedy, ‘Soul Music Dreaming’ and ‘Moving Testimony’; De Cesari and Rigney). Whereas previously the trend was toward studying memory in quite bounded and even atomised ways—for example, through specific sites of memory or particular modes of remembering—nowadays a wide assortment of memory texts are studied in motion. They are tracked as they travel and circulate through networks and across geographical, temporal and other borders. New keywords such as ‘transcultural’ and ‘travelling’ memory (Erll), ‘cosmopolitan’ memory (Levy and Sznaider), and ‘multidirectional’ memory (Rothberg) register this interest in memories on the move, and in the work they do in interconnected worlds. Importantly, these theoretical developments allow for greater consideration of the interpretive possibilities that open out when memories meet. Interpretive intensity arises at the point or moment at which overlaps, entanglements and folds occur.

The focus on memory’s peripatetic ways has drawn attention to the ‘incessant wandering of carriers, media, contents, forms, and practices of memory, their continual “travels” and ongoing transformations through time and space, across social, linguistic and political borders’ (Erll 11). This trend has contributed to a proliferation of studies that track increasingly mobile, shared and distributed concepts and vocabularies, symbols and cultural forms, slogans and memes, such as ‘the sixties’ and ‘soul music’ (Kennedy, ‘Soul Music Dreaming’), or ‘Bloody Sunday’ (Rigney, this collection). It has also led to greater focus on the implications and effects of speeded up and widening modes of distribution and circulation, such as electronic media or global film industries.

Of all memory texts, photographs are recognised as being among the most mobile and this has made them a common focus for studies of memory on the move, across locations, contexts, generations and so forth (Hirsch; Edwards). Recognising that the meanings and evidential force of photographs are not determined at the point of their creation, nor completely contained within a picture’s frame, attention has turned to tracing the ‘paths through which photographs acquire historical meaning and value’ (Tucker and Campt 2. See also Rose). Not only are conditions of original production examined, but also the changing contexts of publication, circulation, reception and critique. At the same time, photographs—and the social practices of photography more broadly—have become powerful sites of analysis within diverse fields of memory studies, not least because they provoke questions about how to conceive of the relationship between past and present, and provide scope for exploring the politics involved in making meanings and constructing histories.

One of the effects of tracing photographs as memory texts on the move is that it brings into contact singular images in one context with singular images in another, in ways that begin to undo or unsettle the qualities and conceits of originality, particularity and individuality. While at one level every photograph ‘captures’ an unrepeatable moment (Barthes), an approach to interpreting photographs that privileges circulation and connection can pull against local and individual or biographical specificities. What opens up by this means are questions about the scale and reach of histories, memories and image-making practices.

In this essay, I begin in a preliminary way to explore some of these ideas and approaches for studying the visual archive of Aboriginal politics in the 1960s, or at least one image in particular. This pursuit was prompted initially by noticing a degree of compositional similarity between a photographic portrait taken in 1963 of Aboriginal activist and leader Charles Perkins [Figure 1] with a slightly earlier photograph of the North American civil rights activist Rosa Parks taken in 1956 [Figure 2]. Their compositional commonality, superficial as it is and accidental as it was, nevertheless provided impetus enough for considering what might be gained (or lost) by studying the two photographs in tandem. I wondered whether the photographic portrait of Charles Perkins, which has of late become a signature image of him because it encapsulates in a single frame a powerful visual statement of his political legacy, owes anything at all to a broader transnational visual history and memory of civil rights activism. What connects these images? How and under what conditions can they be said to articulate with or cross-reference each other? What makes it plausible—and perhaps even productive—to place them within the same visual archive? One way that I have begun to approach their articulation, and the interpretive possibilities it opens up, is by focusing on the ‘bus’ as a common carrier of meanings. In each of the images, the bus functions simultaneously as mundane object, as political stage, as symbolic sign, as iconic image. The ‘bus’ is the common setting in both images, and so I am interested in what cultural and political work the bus does as a carrier, not of people only, but also of meanings, associations and memories. Engaging with this matter takes the discussion into contemporary cultural politics and debate, which serves to introduce a couple of images that ‘reenact’ the originals as well as drawing attention to the ways in which ‘buses’—actually and symbolically—continue to feature in contemporary Australian race politics.

Figure 1: Charles Perkins, 1963. Photographer: Robert MacFarlane. Used with permission of the photographer and the Perkins family.

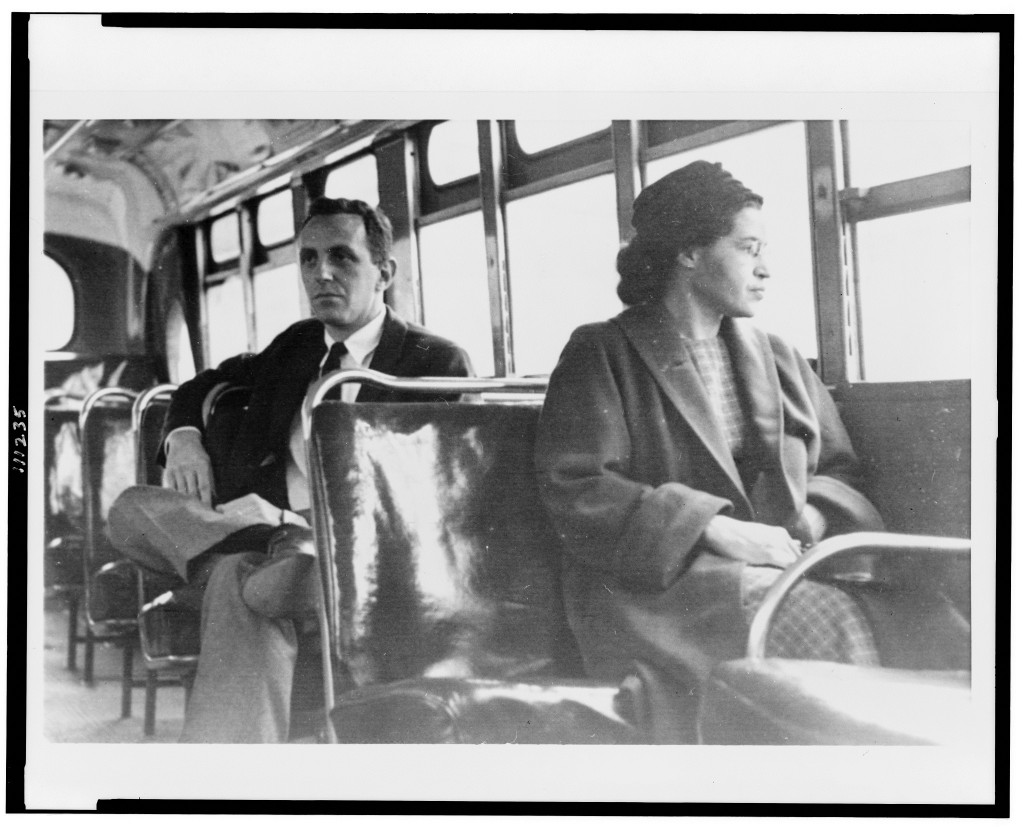

Figure 2: Rosa Parks, 1956. Photographer: United Press. Source: The Library of Congress, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c11235.

Alone on a bus: Perkins, Parks and photographic portraits of activists

To begin, then, with the photograph of a young and handsome Charles Perkins in which he is pictured sitting alone aboard a public bus in Sydney, seemingly lost in thought. The year is 1963, and although descriptive titles and captions given to the photograph are by no means uniform, it is most likely that it was taken as Perkins commuted home from either the University of Sydney, where he had commenced studies that year, or Tranby Aboriginal College in Glebe, where he tutored students, to the flat in Bondi he shared with his wife, Eileen (McFarlane). The photographer was Robert McFarlane, then only twenty-one-years-old, but who, like Perkins, had recently left his hometown of Adelaide and was going places (Newton; Read). They were, then, a couple of young men on the move and in a hurry and this photograph provides evidence of their coming together. It had been McFarlane’s idea to do a photographic profile of Charles Perkins, with the intention of selling it to the widely circulated ‘travel magazine’ Walkabout (McFarlane). Back in Adelaide, where both young men had lived in the early 1960s, McFarlane had noticed that Perkins was gradually gaining a profile as an activist. In the meantime, Perkins had relocated to Sydney, not least because he realised, as he expressed it in his autobiography, ‘that Sydney was the centre of the mass media and this was where I could get an opinion across to people in Australia’ (Perkins 68). Interested as he was in gaining access to the mass media, Perkins was, it seems, a willing photographic subject. Walkabout had a large readership, catering to the ‘middle brow’ (Johnston). But contrary to what is commonly assumed, it does not appear that McFarlane’s ambition for the magazine to do a feature on Perkins ever materialised. A search of the volumes published in the 1960s ended empty-handed.[1]

While the photographic series was created in the early 1960s, its publication and circulation history belongs to later decades, particularly the opening decades of the twenty-first century after Perkins’ death in 2000. Since then, it has become a favored portrait with which to remember—and to commemorate and celebrate—Perkins and his political achievements and legacy. It is, for instance, the image used to publicise an annual oration in his name at the University of Sydney, his alma mater (<http://sydney.edu.au/koori/news/oration.shtml>). It has featured in The First Australians television series and accompanying book (co-produced and edited by Perkins’ daughter Rachel), and was also recently included as a key image within a history of Aboriginal photography and its place in the history and politics of recognition of human rights (Lydon).

It is not difficult to fathom why this photographic portrait appeals. It’s an attractive portrait. Probably more influentially, the photograph includes elements, or visual cues, that work to encapsulate Perkins’ biography and reputation, and to situate him in history—national and transnational. Critical here is that the frame for the image of Perkins is a bus. If there is any stage on which Perkins indubitably made his name as a nationally recognized leader in Aboriginal affairs in Australia, it was aboard a bus.

The story is well known. In 1965, a couple of years after this photograph was taken, Perkins along with other students from the University of Sydney organized a bus tour of rural New South Wales that was aimed at exposing and challenging racial discrimination against Aboriginal people (Curthoys Freedom Ride; Clark; Read; Nugent). Influenced by the very effective protests in the southern states of North America in the early 1960s when university students and other young activists rode buses to challenge racial segregation and discrimination, Perkins and company dubbed their tour a ‘freedom ride’ (Read; Curthoys Freedom Ride).

The confrontations that the bus tour provoked in some country towns launched Perkins onto the national stage and stamped him as a new leader of Aboriginal affairs. It was an event that Perkins would later describe as ‘probably the greatest and most exciting event that I have ever been involved in with Aboriginal affairs’ (Perkins 74). Historian Ann Curthoys, who participated in the freedom ride, concludes that ‘the journey changed many lives; Charles Perkins’ perhaps most of all’ because ‘it catapulted him on to the national stage as a spokesman for Aboriginal rights’ (Curthoys ‘A Journey’ np. See also Curthoys Freedom Ride).

Given this subsequent context, it is not surprising that this photograph of Charles Perkins riding a bus is often published with reference to that later event. For instance, in the richly-illustrated book accompanying the award-winning documentary series First Australians, the photograph is accompanied by a caption that reads: ‘Charles Perkins (Arrente/Kalkadoon) who, with a bus full of Sydney University students, in 1965 toured country New South Wales on a “Freedom Ride”, drawing attention to widespread segregation and the appalling conditions in which Aboriginal people lived’ (Perkins and Langton). Here, as in many other instances, the photograph’s meanings and uses as ‘memory text’ and as ‘historical document’ are blurred. It matters little that the bus on which Perkins was photographed was not the ‘freedom ride’ bus. Nor does it matter that buses in Sydney were not racially segregated and so not sites for political protest. The details do not matter; what’s critical here is the chain of signification that is drawn between Perkins, politics and buses.

Historians of the 1965 NSW Freedom Ride have examined the question of the influence of the North American Civil Rights struggle. Some have, for instance, highlighted the ways in which a student protest outside the US Embassy in response to the violence which erupted in Birmingham, Alabama in May 1963 helped to turn the focus onto racial discrimination in Australia (Read; Clark). They note that the student protestors were challenged on why they were more concerned with distant events than the everyday entrenched racism that affected Aboriginal people’s lives. And they show that that provocation eventually led to the Australian freedom ride in 1965.

Similarly, historians have stressed the impact of Martin Luther King’s writings on Perkins and other Aboriginal activists at the time, as well as their self-conscious adoption of certain political strategies, such as non-violence, staging confrontations, and the importance of images in getting their messages across. Yet, the general consensus among historians has been that while such influences and ideas were significant, they were not imported holus bolus. Rather they were translated and tailored to local conditions.

The differences are evident at many levels, including in regard to the pragmatic as well as political significance of buses. Unlike their counterparts in the US, the Australian students did not catch public and private buses to challenge racial segregation. Rather, they hired a bus to take them to the rural towns where Aboriginal people were subjected to racial discrimination and segregation. Their aim was to see this situation for themselves, and to broadcast it to metropolitan Australia.

In Australia, buses were not, then, primarily social spaces where racial discrimination was practiced and codified. Nor were public buses the stages for organised protests. In the case of the NSW freedom ride, they were a means to an end. Arguably, though, the Australian students’ political action would not have been nearly as effective if they had not travelled by bus since, by the time they set out to examine racism and inequality in their own backyard, buses were already acquiring rich symbolic meanings through the civil rights struggles in full swing in the United States in this period. Like ‘hoses, a bridge, and a preacher’ (Schwarz), buses were already among the iconic images that signaled the history of civil rights and struggles for freedom against racism and inequality. But while historians have considered the history of the NSW Freedom Ride from a transnational perspective, less attention has been given to the visual politics that it created, beyond recognition that the lessons of making sure that actions were staged for visual effect and photographed for the evening news were learnt.

To pursue this point further, I want to consider the second photograph in the pair. It is, as already noted, a photograph that that shares considerable compositional similarity to the photograph of Perkins, although it appears the commonality was by accident rather than design.[2] This is the photograph taken in 1956 of Rosa Parks sitting on a bus, hands clasped in lap, gazing out of the window. If Charles Perkins and buses go together in an Australian imagination, then in North America (and now globally) it is Rosa Parks and buses that are forever entwined. The story of how that intimate association was created is also now well known: in 1955, while travelling home from work in Montgomery, Alabama, 42-year-old Rosa Parks refused to move from her seat to make room for white passengers when directed to do so by the bus driver. Her protest that day led to her arrest, which in turn prompted a year-long bus strike when black people refused to use public buses until the laws changed. Although the event and its circumstances is much mythologised, it is nevertheless widely considered foundational to the Civil Rights struggle and to launching Martin Luther King as one of its main leaders.

This photograph of Rosa Parks sitting on a bus was taken on the day the US Supreme Court handed down its decision that segregation of public buses in Montgomery was unlawful. It is a staged photograph, designed to represent (although not exactly reenact) the protest that had led to the momentous political achievement that the Court’s ruling represented. The white man on the seat behind Parks (a journalist covering the story, who was commandeered for the photograph) is supposed to serve the semiotic function of showing that Parks, a black woman, no longer had to sit behind white passengers. It was, in that sense, designed as a statement of political outcomes and wins—and of new social formations that those political achievements made possible.

But the photograph has circulated not so much for that instructive or illustrative purpose. It has, rather, become an image that frames the story of Rosa Parks herself, which is what also contributes to making it a suitable and productive companion piece for reading with the Perkins photograph. As with the Perkins photograph, what this picture produces is an image of Parks that situates her on the stage on which she made history and her name. And, simultaneously, it presents her as an embodiment of what Leigh Raiford has described as ‘legitimate [black] leadership’ (Raiford). In the cultural production of Rosa Parks as a significant historical figure—as the subject of repeated storytelling, mythmaking and commemoration—above all else she has gained a reputation for steely resolve and quiet dignity, the very qualities that this staged photograph of her accentuates. Critical in conveying such character traits is her comportment. The photograph captures her looking away from the camera and gazing out of the window. Purposefully or otherwise, she strikes a pose of quiet repose.

In the photograph of Perkins, he also directs he gaze not to the camera but out through the window. Biting his thumb, he seems lost in thought, gazing into the middle distance. When I discussed the photograph with him, the photographer Robert McFarlane described Perkins’ look as a ‘thousand yard stare’, the title of a photograph by the American photographer David Douglas Duncan of a US soldier in Korea in 1950. It is a term that was coined to describe ‘the unfocused gaze of a battle-weary soldier’. But Perkins’ look is not necessarily one of world-weariness. When placed alongside the Parks image, what emerges is the sense that they are each looking into the future. The photographs imply a privileged perspective that belongs to the political activist. We are tempted to read them contemplating what their actions now might mean for a later time. And we might go even further to suggest that the photographs can be read as scenes of seeing—or envisioning—a world distinct from the present, in which, for instance, racial inequality has become a thing of the past. As another compositional element, the window is significant here (Hellman). The window is the classic symbol of vision, and so what the camera provides in each of the photographs is an image of the act of envisioning by means of capturing Parks and Perkins respectively as they look out through a bus’s wall of windows.

In this way, in both images the bus setting does more than function to remind the viewer of the public stage for Parks’ and Perkins’ most defining and far-reaching political interventions, or indeed to situate them instantly within the era of postwar civil rights movement for which buses, among other things, became a shorthand sign (Schwarz). Tellingly, the bus in both photographs works to contain and frame their subjects, providing what seems like a cocooned space for personal reflection and meditation. It is public space for private thought—and thus for a scene of what political activism looks like beyond the protest itself. Politics, the photographs suggest, is action and thought. In the photographs, the interior of the bus fills the entire frame. We see nothing of the world outside—only Parks and Perkins look out to what lies beyond. Rather, within the picture, the bus constitutes an entire world. It is simultaneously social space and personal space, both a site of historical and biographical significance, and a space equally of interiority and exteriority.

Like the photograph of Parks, the photograph of Perkins is nowadays commonly interpreted as a portrait of him as fully formed political leader. Historian Jane Lydon, for instance, has recently argued that at the time of its creation it ‘showed [that] here was a serious, charismatic presence symbolising a new kind of leader’ (Lydon). While there is certainly truth in this, it is nevertheless a reading of the photograph that is overlaid by knowledge of Perkins’ later history and biography. Paying careful attention to the actual conditions of its creation might suggest a different interpretation. According to his biographer, Peter Read, Perkins was at something of a crossroads at this point in his life. He was not sure which way he was going to go. Read characterises Perkins as still a work in progress. He describes him variously as ‘an energetic but nervous public speaker’, of having trouble breaking into the Aboriginal community and political networks in NSW, and as undecided and uncertain about his future. Even when his political profile grew and his place in the world was more assured, ‘though everybody wanted his support’, Read writes, ‘he remained a little lonely’ (Read 124).

When in early 1963 the young Robert McFarlane took the now famous photograph, Perkins had not yet made the history that would define him and buses meant nothing more or less to him than a mode of transportation. Even though he was slowly gaining a reputation for his political activism, it was—and he was—not yet certain that he would become the recognized leader that he became. Looking closely at the photograph as picture rather than image (Mitchell), it emerges more clearly as a portrait marked as much by uncertainty, ambivalence and nervous anticipation as by substance, style and seriousness. Certainly, when it is placed back within the entire series of photographs that McFarlane created, rather than singled out for special attention, this quality comes through strongly. All the photographs that McFarlane took show Perkins alone, and set against a backdrop of a larger and imposing world. In each of them, he looks a little unsure of himself. The habit of biting his thumb appears more than once. One particularly striking image in the series shows him crouching down on the stone path that cuts across the University of Sydney’s imposing Main Quadrangle, briefcase beside him, to tie up his shoelace. The juxtaposition of the august setting with the humble act is what gives that image its power. And the bus in this other photograph serves a similar function: it reinforces his anonymity and perhaps even alienation, while it also suggests that he was ‘going places’—although where that was, was not yet clear. Yet, as Buck-Morss reminds us, ‘value added to the image by the collective imagination has the power to … disregard original intent’ (Buck-Morss).

The bus as stage for contemporary race politics

During the time I have been dwelling on this pair of photographs of Charles Perkins and Rosa Parks each sitting on a bus, an uncanny thing has happened. Beginning in early 2013, some stories about racist incidents occurring on public buses in Australia began to receive media attention. It began when Jeremy Fernandez, a journalist and newsreader for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) in Sydney, was subjected to a ‘racist rant’ as he commuted to work in company with his two-year-old daughter. When the bus driver told Fernandez—and not the alleged abuser—to get off the bus, Fernandez retorted: ‘I’m not going anywhere, I have a right to be on this bus and on this seat’. While the incident was unfolding, Fernandez took to twitter, writing: ‘Just had my own Rosa Parks moment: Kept my seat on a #Sydney Bus after being called a black c**t & told to go back to my country’. He later explained that: ‘I didn’t want to cower because of my colour, I’m staying here on principle’ (Fernandez cited in Young). As a professional journalist with privileged access to the media, Fernandez was able to ensure that the incident was put on public record and reached a wide audience. Speaking on ABC radio, for instance, he elaborated:

I thought I could move and then I had a flashback to a very famous case of a woman on a bus in the US, a black woman, who was told to give up her seat. And I thought no, I’m having my own Rosa Parks moment, I’m not moving from this seat because it has turned into a racial issue. I said I’m not going anywhere, I’ve just been called a black c-word, I am not going anywhere, I’ve not done anything wrong, I have a right to sit here, I’m going to stay here. (cited in Young)

Because Fernandez’ framed the incident by drawing the analogy to Rosa Parks, it was represented and analysed in racial terms (Hocking).

There is little doubt that making the parallel between Fernandez’s own experience and the precedent set by Rosa Parks was an effective strategy. The evocation of Rosa Parks’ name provided the narrative frame through which to understand the incident not as idiosyncratic and aberrant, but as social and public. It was a ‘racist’ incident. Fernandez’ narration of it worked to connect the culprit’s actions to a long lineage and a global phenomenon. It also provided a justification for the choices he made, in particular refusing to obey the driver’s demand and by not remaining silent. He made this personal attack a public and civic matter.

This appears to have had a flow on effect. It seems to have been the trigger for heightened public awareness of racism on public transport, in Sydney and beyond, including evidence of the unpreparedness on the part of some commuters (members of the public) to let it go unnoticed or unchallenged. Before long, reports of other racist incidents on public transport—buses especially but also commuter trains—began to appear in the Australian media with some regularity. While Fernandez’ story made the news through his professional access to public media outlets, subsequent reports of similar incidents relied more often on modes of citizen journalism. Some witnesses surreptitiously recorded incidents on mobile phones, which they then uploaded to social media. From there, the stories made it into the mainstream media. The number of like incidents reported quickly multiplied, so much so that it seemed for a time that Australia was in the grip of an epidemic of racist outbursts on public transport. The racism-on-a-public-bus-incident soon moved from real life into fiction as it was written into the script of a popular television series (Time of Our Lives). It was also used in a televisual public education campaign called the ‘Invisible Discriminator’, which aimed to show that subtle discrimination against Aboriginal people contributed to anxiety and depression (<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MvTyI41PvTk>). Buses, it seems, continue to function as public spaces for social expressions of racial discrimination as well as the stage for the refusal to condone it. This owes much to the cultural work that has gone into remembering the civil rights struggle—and Rosa Parks in particular—through a series of condensed symbols, including buses as carriers of meaning that can be ‘transported’ into diverse contexts to making shared meanings from individual and localised experiences, situations and incidents.

The bus on which Rosa Parks staged her protest in 1955 has come to standstill. About a decade ago it was salvaged as a wreck, and has since been completely restored. It is now housed in The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn Michigan. Restoring machinery and transport to its former glory is a hallmark of The Henry Ford Museum. As Kerstin Barndt notes: ‘The magic of original settings, painstakingly reconstructed, is … a central aspect of the visitor experience’ (Barndt 381).

Within the space of The Henry Ford Museum, the Rosa Parks bus is presented in such a way as to fulfill a number of overlapping functions. It not only celebrates the story of Rosa Parks herself; it is also the ‘vehicle’ through which to present the history and significance of the Civil Rights struggle. As a Museum devoted to histories of transportation, it perhaps not surprising that it gives prominence to buses as public and social spaces, where ‘races’ encountered each other in close proximity as they went about their daily lives. According to the Museum’s website, for instance, ‘transportation was one of the most volatile arenas for race relations’. It further notes that ‘city buses were lightning rods for civil rights activists’, and that the ‘civil rights movement began on a bus’ (<http://www.thehenryford.org/exhibits/rosaparks/>).

In addition, in a more personalised mode of memory, reference is made to Rosa Parks’ childhood recollections of seeing white school children travelling to schools on buses while she and other black children walked. She is quoted (in italics) as saying that ‘the bus was among the first ways I realized there was a black world and a white world’ (<http://www.thehenryford.org/exhibits/rosaparks/>). Here, as in the photograph, the bus is represented as more than mundane transportation: it is presented as carrying social, political, historical and personal meanings and associations that would later influence political action and lead ultimately to social change.

At The Henry Ford Museum, visitors are actively encouraged to interact with the exhibits as part of an immersive museum experience. They are invited to step aboard the Rosa Parks bus, and by so doing they vicariously experience a past when buses were racially segregated. More especially, they can imagine themselves as Rosa Parks, refusing to accept the status quo by staying put. This is exactly what Barack Obama did on the day he visited the Museum and stepped aboard the Rosa Parks bus. He sat down on the seat where Rosa Parks had sat [Figure 3]. Momentarily, he assumed her pose. And it was that moment—when Barack Obama played at being Rosa Parks—which the photographer accompanying him captured.

Figure 3: Barack Obama, 2012. Photographer: Pete Souza. Source: Wikicommons.

Obama knows well the story of Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat in 1955. He is no doubt very familiar with the staged photograph of her in 1956. As Bill Schwarz notes, the civil rights struggle is a ‘history which Obama knows from the inside … it had entered his interior life even as a young child’ (140). As Obama explained in his autobiography, Dreams of My Father, he had been brought up by his mother on a diet of images and stories about the civil rights movement. He knows that past mainly through images and photographs— ‘mostly, the grainy black-and-white footage that appears every February during Black History Month, the same images that my mother had offered me as a child’ (Obama). Those images would shape his historical consciousness. They constituted ‘a series of images … of a past I had never known’ (Obama).

The photograph of Barack Obama-being-Rosa Parks was published instantly. It was posted on the White House’s official website and it was tweeted. It circulated widely in the United States and globally, as it was republished repeatedly across print and electronic media. Its effects and its reception were multiple and mixed. At the most basic level, it was part of the ongoing cultural processes of keeping alive the legacy of Rosa Parks, of the Montgomery bus strikes, and of the civil rights struggle. This was made explicit when the photograph was re-tweeted by the White House later in 2012 to mark the fifty-seventh anniversary of Parks’ protest in an act of commemoration (Jones). But that was also a gesture that met with strong criticism, as some saw it as yet another instance of Obama mobilising the memory of the civil rights movement for his own political mileage (Jones). One obvious interpretation of the photograph is to ‘watch it’ (Azouly) as yet another instance of the ways in which Obama’s presidency has been constructed, presented and imagined as a direct inheritance from, and fulfilment of, the civil rights movement (Sugrue). But that narrative has become an increasingly fraught and contested proposition within contemporary North American public debate, as Obama has been criticised on his ‘race relations’ record. That disgruntlement might help to explain in part why the re-tweet of the photograph of him on the bus to commemorate Rosa Parks appears in some quarters to have misfired (Jones).

The 1963 portrait of Charles Perkins was also recently the subject of a photographic reenactment, but one not nearly so literal as that enacted by Obama aboard the Rosa Parks bus. In 2014, the Brisbane-based photographer, Michael Cook, included a re-creation of the photograph of Charles Perkins seated on a bus in series he produced under the title ‘Majority Rules’ [Figure 4]. For this reworking, Cook takes the photograph of Perkins sitting solitarily on a mid-twentieth-century urban bus, and recasts that ordinary public space as occupied exclusively by stylish Aboriginal men. In the new image, the same man, always wearing the identical attire of a city-worker (tie, waistcoat, shirt), is repeated about twenty times but he adopts various poses that are common to commuters. He stares vacantly, sleeps, reads, stands, studiously ignores and fazes out. The image includes subtle inter-textual references to the photograph on which it is based. For instance, the man sitting where Perkins was photographed assumes a similar pose as he had gazing out of the window. Another man pictured at the front of the bus is reading Walkabout magazine, where the original photograph of Perkins was intended for publication, and where sometimes erroneously it is still believed it was.

Figure 4: Majority Rule (Bus), 2013. Photographer: Michael Cook. Used with permission.

By imagining a past that did not exist, the reworked (or reenacted) photograph is designed as a provocation for thinking about what if—for imagining an Australian past as if it had been otherwise and by that means reminding contemporary audiences about colonial legacies. This is reenactment, and cultural aesthetics, as politics (Agnew). In this sense, then, rather than reenact the photograph of Perkins in a spirit of homage, as in the case of Obama’s reenactment of the Rosa Parks photograph, Michael Cook’s photographic reenactment works rather to disrupt an easy progressive sense of historical time. Using the visual archive recursively, he creates an imagined space that lies somewhere between utopia and loss. Rather than being comforted by progress—or the promise of it—in Michael Cook’s reconstitution of Robert McFarlane’s intimate portrait of Perkins, the viewer is more likely to be left with a sense of strangeness, of a scene so utterly unfamiliar that it appears dreamlike rather than documentary.

Conclusion

This discussion has returned, by a somewhat circuitous route, to the photograph with which I began and which lies at the core of the concerns of this essay. It should be clear by now that the singular photograph of Charles Perkins is emerging as a signature image within the broader visual archive of Aboriginal politics of the 1960s, but there was nothing inevitable about this at the time of the photograph’s creation. Its symbolism was latent and its significance belated. The resonances it would come to acquire depended on processes and contexts that occurred well beyond the creation of the photograph itself. Here I have mapped just some of those cultural processes and forces, focusing in particular on the ways in which the seemingly ordinary setting of the bus as the frame for the portrait of Perkins gained symbolic weight and traction through the conjunction of biographical and historical factors particular to Perkins himself, as well as through the transnational articulations of history, politics, and image-making. To draw this out, I have focused in particular on the meanings of the bus, which is perhaps fitting for a discussion that is concerned with mobility. This focus has been enabled in part by not only retelling the story of the making of Perkins’ political profile and reputation via his emerging leadership qualities during the 1965 NSW Freedom Ride, important as that is to the meanings which the image has accrued. Just as importantly, it has also been pursued by putting the photograph in conversation with other photographs and visual histories from other times and places but with which it can be seen to share some compositional commonality. This method has allowed some engagement with the call to consider the transnational frames and scales of memory, while not losing sight of the local, familial and personal conditions in which images, events and lives are made meaningful and memorable.

Maria Nugent is Fellow in the School of History’s Australian Centre for Indigenous History at the Australian National University. She was an Australian Research Council Future Fellow (2011-2015) and Visiting Professor of Australian Studies at the University of Tokyo (2015–2016). She publishes on Australian Indigenous and settler-colonial history and memory. Her most recent book (coedited with Sarah Carter) is Mistress of Everything: Queen Victoria in Indigenous Worlds (Manchester University Press, 2016).

Notes

[1] A search of Walkabout magazine for the 1960s reveals that the photograph was not published in that journal. It is possible that it was published in another magazine at the time, but other searches have not yet located it in published form in the 1960s.

[2] When I asked Robert McFarlane if he had been aware of the Rosa Parks photograph, he said not. He was more influenced by American photographers of an earlier period, like Lewis Hine, than by the civil rights photographers who were beginning to gain notice in this period. Also, as far as it is possible to tell, it does not appear that the Rosa Parks image circulated widely in Australia around the time it was created.

Works cited

Agnew, Vanessa. ‘History’s Affective Turn: Historical Reenactment and its Work in the Present.’ Rethinking History (Special Issue: ‘Reenactment’) 11.3 (2007): 299-312.

Azouly, Arielle. The Civil Contract of Photography. London: Zone Books, 2008.

Barndt, Kerstin. ‘Fordist Nostalgia: History and Experience at The Henry Ford.’ Rethinking History (Special Issue: ‘Reenactment’) 11.3 (2007): 379-410.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Buck-Morss Susan. ‘Obama and the image.’ Culture, Theory and Critique 50:2-3 (2009): 145-64.

Clark, Jennifer. Aborigines and Activism: Race and the coming of the sixties to Australia. Perth: UWA Press, 2008.

Curthoys, Ann. Freedom Ride: A Freedom Rider Remembers. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 2002.

—. ‘A Journey to Fight Racial Discrimination: How a Bus Load of Youngsters Rode for Equal Rights in Australia.’ Australian Geographic 97 (27 May 2010). <http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/history-culture/2010/05/freedom-ride-a-journey-to-fight-racial-discrimination>. 9 Aug. 2012.

De Cesari, Chiara and Ann Rigney, eds. Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014.

Edwards, Elizabeth. Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford: Berg, 2001.

Erll, Astrid. ‘Travelling Memory.’ Parallax 17.4 (2011): 4-18.

Hellman, Karen. The Window in Photographs. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust, 2013.

Hirsch, Marianne. ‘Projected Memory: Holocaust Photographs in Personal and Public Fantasy.’ Ed Mieke Bal, Jonathan Crewe and Leo Spitzer. Acts of Memory: Cultural Recall in the Present. Hanover, NH: UP of New England 1999. 3-23.

Hocking, Courtney. ‘Why Are There So Many Racist Outbursts on Public Transport?’ The Guardian (Australian Edition) 4 July 2014. <http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/04/why-are-there-so-many-racist-outbursts-on-public-transport>. 15 Nov. 2015.

Johnston, Anna. ‘Reading Walkabout in Japan: Travel, Mobility and Place-making in Walkabout Magazine.’ Politics of Australia 2015: What Japan Can Learn. Australia-Japan Foundation, 2015.

Jones, Jonathan. ‘What Was on Obama’s Mind as He Sat on the Rosa Parks Bus?’ The Guardian, 3 December 2013.

Kennedy, Rosanne. ‘Moving Testimony: Human Rights, Palestinian Memory, and the Transnational Public Sphere.’ Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales. Ed Chiara De Cesari and Ann Rigney. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014. 51-78.

—. ‘Soul Music Dreaming: The Sapphires, the 1960s and Transnational Memory.’ Memory Studies 6.3 (2013): 331-44.

Levy, Daniel and Natan Sznaider. The Holocaust and Memory in the Global Age. Philadelphia, PA: Temple UP, 2005.

Lydon, Jane. The Flash of Recognition: Photography and the Emergence of Indigenous Rights. Sydney: NewSouth Books, 2012.

Martin-Chew, Louise. Michael Cook: Majority Rule [exhibition catalogue], Brisbane: Andrew Baker Art Dealer, 2014.

McFarlane, Robert. Personal interview (by telephone). 18 March 2014.

Mitchell, W.J.T. ‘Showing Seeing: A Critique of Visual Culture.’ Journal of Visual Culture 1:2 (2002): 165-81.

Newton, Gael. ‘Robert McFarlane.’ Robert McFarlane: Received Moments, Photography 1961-2009. Ed. Sarah Johnson. Manly, NSW: Manly Art Gallery and Museum, 2009.

Nugent, Maria. ‘Sites of Segregation / Sites of Memory: Remembrance and “Race” in Australia.’ Memory Studies 6.3 (2013): 299-309.

Obama, Barack. Dreams of My Father. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2008.

Perkins, Charles. A Bastard Like Me. Sydney: Ure Smith, 1975.

Perkins, Rachel and Marcia Langton. First Australians: An Illustrated History. Melbourne: Miegunyah Press, 2010.

Raiford, Leigh. Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

—. ‘Photography and the Practices of Critical Black Memory.’ History and Theory Theme Issue 48 (December 2009): 112-29.

Read, Peter. Charles Perkins: A Biography. Ringwood, Vic.: Viking, 1990.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: Sage, 2013.

Rothberg, Michael. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonisation. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2009.

Schwarz, Bill. ‘“Our Unadmitted Sorrow”: the Rhetorics of Civil Rights Photography.’ History Workshop Journal 72 (2011): 141-55.

Sugrue, Thomas J. Not Even Past: Barack Obama and the Burden of Race. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2010.

Tucker, Jennifer and Tina Campt. ‘Entwined Practices: Engagements with Photography in Historical Inquiry.’ History and Theory Theme Issue 48 (December 2009): 1-8.

Young, Matt. ‘ABC Newsreader Kicked Off Bus After Enduring Abuse.’ news.com.au. <http://www.news.com.au/entertainment/tv/abc-journalist-cops-racist-rant-on-sydney-bus/story-e6frfmyi-1226573416717>. 8 Feb. 2013.